MULHOLLAND DRIVE: A Fascinating Story Behind the Masterpiece

It lacks violence, shady characters, ambiguous yet unsettling situations, and images that settle in the human subconscious for a lifetime.

No dwarfs dance in it, no one seeks salvation between the ribs of an old radiator, it’s hard to find any severed ear in the thick grass, and behind the doors of American homes, life goes on normally, undisturbed by any demonic force moving on owl’s wings. Yet, the very heart of the story about Alvin Straight beats to the same rhythm as the turbulent Lost Highway, the reflective The Elephant Man, or the surreal Twin Peaks. At the center of all the stories told by the American is the human being, whom the director approaches with empathy, no matter what they’ve done or what situation they find themselves in. Greg Olson once said that Lynch realizes that the darker the sky, the better the stars shine on it. From this perspective, the finale of The Straight Story is the quintessence of the director’s cinema, and the film itself is truly a classic Lynchian tale about a man and his weaknesses, strengths, and dreams. In making this film, Lynch let down the guard of surrealist imagery and visual oddities, which is incredibly important and valuable for understanding his cinema. No matter what darkness surrounds Lynch’s characters, the American always seeks that ephemeral gleam of light that will offer an escape from the labyrinths created at the crossroads of the external and internal worlds of his characters. Mulholland Drive

It is remarkable that between his most widely discussed films, Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive, Lynch found time to create the story of Straight. The criticism he faced after the release of the former film could have easily prevented him from making Mulholland Drive, were it not for the positive press that began to surround his name after 1999 and his collaboration with Walt Disney, who became the official distributor of The Straight Story following the Cannes Film Festival. Moreover, the story of a woman who, after a terrible accident on one of America’s iconic highways, lost her memory and vanished into the darkness separating her from the lights of Los Angeles, was conceived several years before the real Alvin Straight mounted his lawnmower to settle a long-standing feud with his brother. But, let’s go in order.

The premature death of a rock star

The Mulholland Drive theme first emerged during the filming of Twin Peaks, when David Lynch and Mark Frost began making plans for their potential collaboration after the series ended. Due to the immense success of the first season of Twin Peaks, but also the limitations imposed by the television format, the creators decided it would be worthwhile to continue certain storylines and narratives outside the main series by creating spin-offs. The first spin-off planned was to focus on the character of Audrey Horne, who had electrified the audience of the show. Before the second part of the series aired, the creators received countless letters from fans requesting more attention be given to the relationship between Audrey and Agent Cooper in upcoming episodes. Initially, Lynch and Frost had envisioned a spin-off dedicated to this character, which would take place in Los Angeles. Horne would have gone there to start an acting career, much like Diane Selwyn from Mulholland Drive.

The painful failure of the second season of Twin Peaks made any thoughts of continuing the story on television impossible. Lynch almost failed to bring Fire Walk with Me to the screen, a film that completed the story of Laura Palmer. Therefore, the idea of securing funding for another series revolving around the Twin Peaks themes seemed simply naive. Audrey Horne’s story had to be shelved.

Lynch’s subsequent experiences with the television medium throughout the 1990s increasingly convinced him that he would prefer to remain focused on cinema and painting. Directly after the turmoil surrounding the production and airing of the second season of Twin Peaks, which was largely destroyed by the actions of ABC executives, there was a drastic end to his comedic show On the Air, another collaboration between Lynch and Frost. The series, initially planned for seven episodes, was canceled after just three episodes, and to make matters worse, they were aired out of order. The Hotel Room episode, created by Lynch and Barry Gifford for HBO, was almost instantly forgotten as well. The pressure from network executives, struggles with securing a good time slot, creative vision clashes, and the requirement to fit episodes within the network’s specified time limits were just a few of the reasons that led Lynch to look at television with increasing reluctance.

Hotel Room indeed premiered on HBO between January 8 and 9, 1993, while Lost Highway was released in 1997. Lynch had a four-year period between these two films, during which he could rest from the battles with network executives responsible for programming decisions on TV stations. In June 1998, Lynch received the completed script for The Straight Story. Around the same time, Mulholland Drive started to form in his mind. While working on the film about Alvin Straight, in August 1998, Lynch found time to revisit ABC’s headquarters with a script he had written together with Joyce Eliason, a writer involved in numerous television productions.

The choice of ABC for the development of Mulholland Drive might seem strange at first, considering that this network was responsible for the cancellation of On the Air and the chaotic airing of Twin Peaks’ second season. However, Lynch knew that some people still working at the station might be interested in his return to the small screen. That’s exactly what happened. The initial pitch of the idea to ABC, specifically to Jamie Tarses and Steve Tao, was said to have been met with great excitement. Lynch took a somewhat risky and audacious approach to this meeting. The outline of the script presented to Tarses and Tao was very brief. Lynch began telling them the story’s opening, which, as later experiences would show, matched the prologue of the cinematic version of Mulholland Drive.

The director started the story with a slow drive down a road bathed in soft lights, concluding with a woman who barely survived an accident and, in total shock, vanished into the darkness surrounding the hills of Los Angeles. When Tarses and Tao asked about the rest of the story, Lynch responded that they wouldn’t know until they put up the money for a pilot episode. After a short consultation, Tarses, Tao, and Stu Bloomberg offered Lynch $4.5 million for the first episode, which was to be more like a television movie introducing viewers to the new series. An additional $2.5 million came from Tony Krantz, a friend of Lynch, who negotiated with Touchstone Pictures, then under Disney’s umbrella. In exchange for the extra funds, Lynch agreed to create an alternative ending for foreign markets. The purpose of this ending was to make the viewer feel they had watched a finished film rather than a pilot episode, as Touchstone – under the Buena Vista brand – was planning to distribute the episode in international markets, particularly Europe and Asia. Lynch was, of course, not thrilled with this idea, but the substantial increase in the budget and the persuasion of Krantz, who had once been involved in talks about a Twin Peaks spin-off centered around Audrey Horne, eventually convinced him to accept the concept.

On January 4, 1998, a 92-page pilot script for Mulholland Drive landed on the most important desk at ABC. The studio was pleased with the results. Steve Tao, in conversations with the press, even likened Twin Peaks to a rock star who died prematurely in a plane crash. After its sudden death, people craved its music even more. According to Tao, Mulholland Drive was meant to resurrect the star and bring it back to the stage. Lynch received the green light to proceed with production, but due to commitments tied to The Straight Story, things couldn’t progress as quickly as one might expect. This likely contributed to the unconventional casting process for Mulholland Drive, even by Lynch’s standards. Naomi Watts, Laura Harring, and Justin Theroux were cast based solely on headshots sent by their agents, with subsequent meetings being mere formalities—though the actors themselves were unaware of this.

Each of the three meetings came with its own unique story. For Watts and Theroux, long flights played a significant role. Both actors met Lynch immediately after stepping off their respective flights, looking less than polished. In Theroux’s case, Lynch found his disheveled appearance appealing, which inspired the scruffy, chaotic look of Adam Kesher, Theroux’s character in the film. Watts, on the other hand, was instructed to check into a hotel, get some rest, and transform herself into someone who looked like an aspiring young starlet. The results of her makeover must have been impressive, as Lynch confirmed her casting after their second meeting.

Laura Harring’s casting story was perhaps the most striking. On her way to meet Lynch, she was involved in a car accident. Though the collision was minor, it seemed almost fateful when Harring later received the script and realized her character’s story began with a severe car crash. For Harring, this coincidence felt like destiny had played a role in securing her for the part. Such serendipitous events and Lynch’s instinctive approach to casting only added to the mystique surrounding Mulholland Drive. These choices would later prove pivotal in shaping the iconic and dreamlike atmosphere of the film.

In addition to new faces, the cast also included more recognizable names and individuals already part of Lynch’s cinematic world. Michael J. Anderson, known for his portrayal of The Man from Another Place—the dancing dwarf from the iconic Red Room in Twin Peaks—appeared in a cameo role as Mr. Roque. Reflecting on his role, Anderson admitted he never understood, and probably never will, the reasoning behind Lynch’s decision to cast him, at just 109 centimeters tall, as a mysterious and imposing businessman. To achieve the desired effect, a special costume with prosthetic legs was mounted to a chair, a process that reportedly took a significant amount of time to prepare. Both in the television pilot and the film version of Mulholland Drive, Anderson had just one word of dialogue: “yes.” One might question the logic behind this choice, but in the context of Lynch’s work, the question itself would seem almost humorous.

It’s also worth mentioning Ann Miller’s role in the film, as she concluded her 70-year-long career on the set of Mulholland Drive. This casting decision undoubtedly had a lot to do with one of Lynch’s favorite films and a key inspiration for the story of Diane Selwyn—Sunset Boulevard. In the pilot of Mulholland Drive, when a street sign bearing the titular road’s name appears, the background features the theme music from Billy Wilder’s brilliant film. In the cinematic version, this music was replaced due to the high cost of securing the rights. Casting Miller, a woman who at that time was one of the last professionally active actresses to remember several eras of Hollywood’s development, was clearly a tribute to the times that gave birth to the Dream Factory.

Eighty-eight minutes (two episodes of the series) allocated to the pilot episode of the series were deemed too long by ABC, which demanded the material be re-edited to fit the aforementioned time constraints. This was likely a tactic, albeit an inelegant one, to push Lynch out of the project. The executives at ABC were well aware of Lynch’s aversion to interference in his work and knew the history of what had happened to him during the production of Dune, which, due to meddling from the Laurentiis family, essentially became a different film. However, Lynch refused to back down and, with the help of his wife, Mary Sweeney, re-edited Mulholland Drive to the duration required by the network.

The re-editing process necessitated the removal of numerous scenes that ABC deemed unsuitable for television. Among the cuts were a close-up of dog feces in the courtyard of the building managed by Ann Miller’s character (an extended shot deliberately prolonged by Lynch in the film version), segments showing the character smoking cigarettes, and several scenes depicting violence. The network’s aversion to showing blood stemmed from the Columbine High School massacre on April 20, 1999. This tragic event, later meticulously reconstructed by Gus Van Sant in Elephant (2003), had a profound impact on American popular culture, including television, which, along with other modern media, was heavily criticized at the time for allegedly promoting violence and having a destructive influence on young people’s minds.

Despite delivering a shortened version of the pilot, ABC still had numerous objections to Lynch’s production. They were dissatisfied with the non-linear storyline, the slow pace of the plot, and the casting of Naomi Watts and Laura Harring in the lead roles, as the network deemed them too old. Adding insult to injury, ABC thought Watts seemed too innocent and Harring acted like a zombie (sic!).

Just before Lynch was set to depart for the Cannes Film Festival, where he was to present The Straight Story, Tony Krantz called him with disappointing news: ABC was not interested in airing Mulholland Drive in any form. The slot in the fall schedule initially earmarked for Lynch’s series was instead filled by Wasteland, a youth-focused drama from Kevin Williamson, best known for his screenplay for Scream (1996). Ironically, Wasteland was canceled after just thirteen episodes.

The buzz surrounding The Straight Story motivated Lynch to seek alternatives for Mulholland Drive. He pitched the project to two other major players in the U.S. television market. Unfortunately, neither HBO nor Fox TV expressed interest in producing a miniseries based on the pilot episode. Following these setbacks, Lynch unequivocally declared his departure from television. He stuck to this decision for seventeen years until, in 2017, the third season of Twin Peaks was brought to life on Showtime.

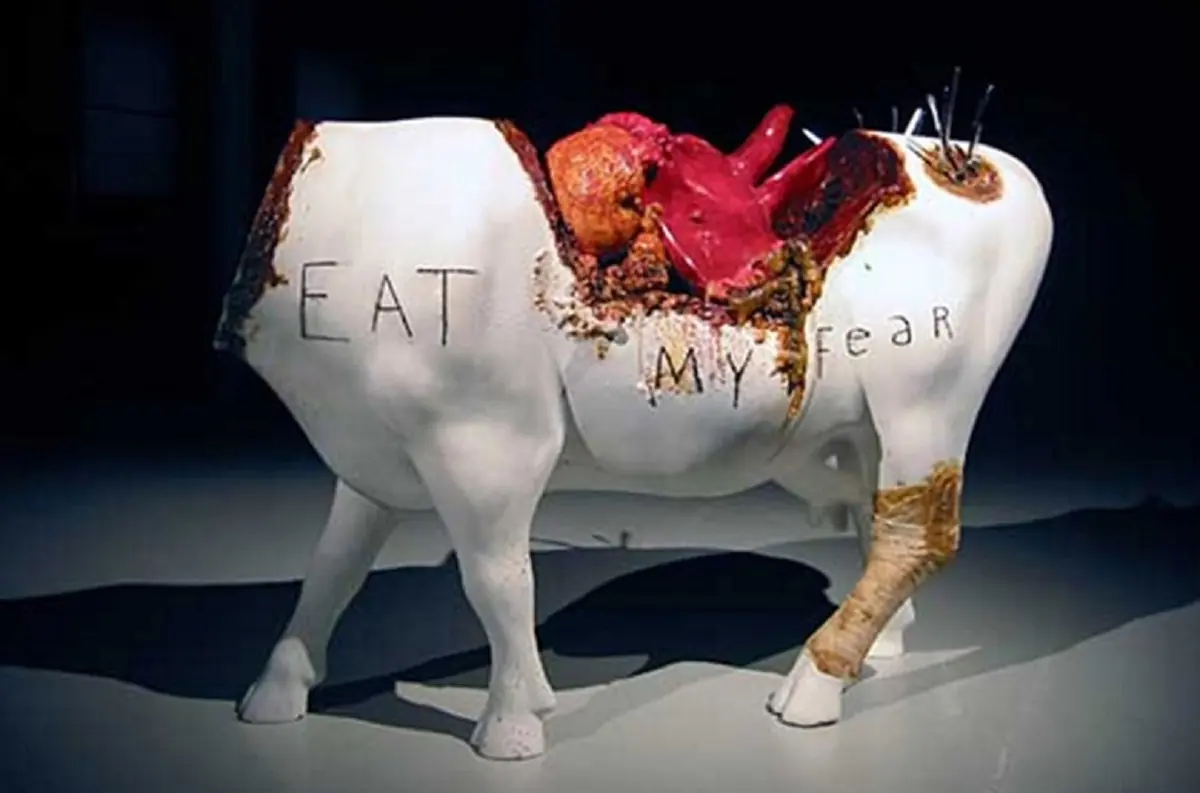

Charles Manson’s Cow

After Mulholland Drive was rejected by American television networks and a distributor was secured for The Straight Story, David Lynch planned to step back from the spotlight for a while. However, this didn’t mean lounging in a cozy robe at home. The director quickly found more intriguing activities to occupy his time.

Though Lynch is generally apolitical—over the course of his career, he has said little on the topic beyond mentioning that, as a Boy Scout, he attended one of President Kennedy’s visits and once voted for Ronald Reagan—he decided to create a nearly 30-minute campaign spot for John Hagelin. Hagelin was a presidential candidate running under the Natural Law Party, which had strong ties to the American Transcendental Meditation movement inspired by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s teachings, a philosophy Lynch has long supported and promoted. Just a few years later, in 2005, Hagelin became a board member of the David Lynch Foundation, a non-profit organization founded by Lynch to spread awareness of meditation, particularly among children and individuals in difficult life situations, such as immigrants, war veterans, and the homeless.

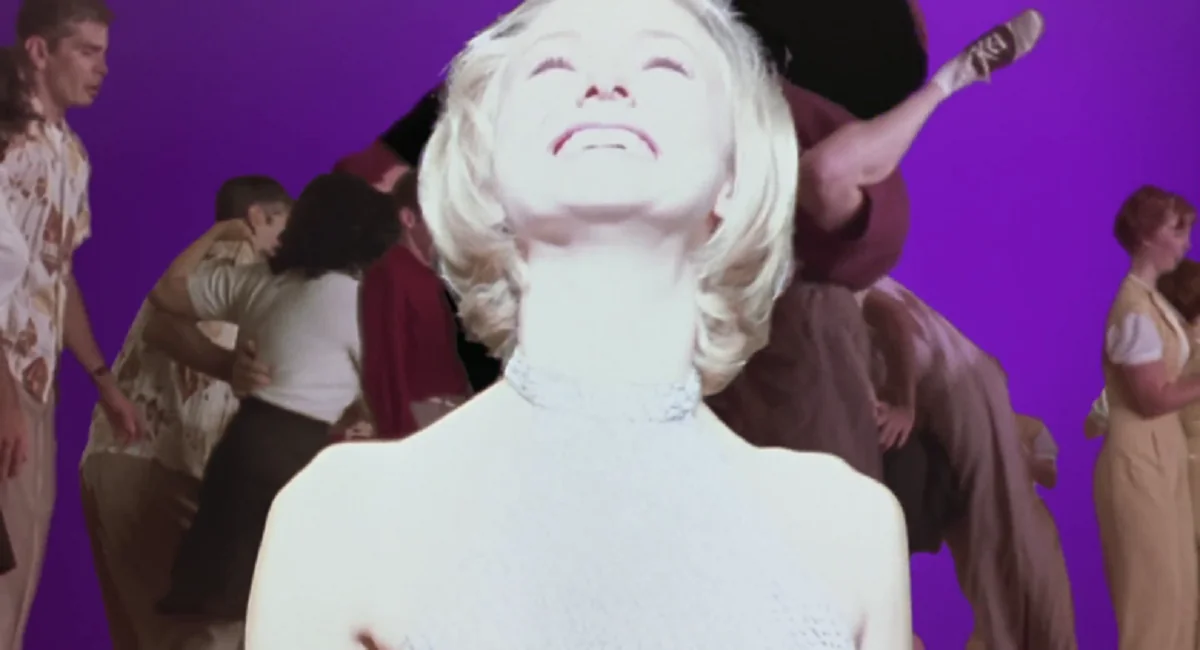

During Sony’s promotional campaign for the PlayStation 2 at the end of the 20th century, Lynch was chosen to create a short commercial for the European market. The advertisement, intended for cinema screenings, was titled The Third Place and filmed over two days in Los Angeles. Scott Billups handled the cinematography, while the music was composed by John Neff, who collaborated with Lynch between April 1998 and March 2000 to record an album titled BlueBOB (released in December 2001). Sony’s decision to entrust Lynch with directing an ad was bold. Considering that their product was meant to be a source of entertainment, Lynch’s ad, which seemed to transport players into a dreamlike nightmare world, risked producing the opposite effect. From today’s perspective, the commercial might feel dated, but the titular Third Place guide—a dapper man with the head of a mallard duck—still retains a unique charm.

In 2000, New York City hosted a grand parade of artificial cows made from fiberglass. Most of the exhibits were prepared by children from local schools. Finished figures were delivered to selected schools along with decorative materials, allowing kids to transform them into a kaleidoscope of colors through their creativity. Professional artists were also invited to participate, and among them was David Lynch. Fresh off the release of The Straight Story, he seemed an ideal candidate for this family-friendly event. Organizers assured him he could let his imagination run wild to make his cow truly stand out.

However, the final result exceeded even their wildest expectations—and not in the way they hoped. When New York City Parks Commissioner Henry Stern saw Lynch’s cow, he reportedly said it must have been designed by Charles Manson himself and flatly refused to display it in public. The event organizers also decided against showcasing the sculpture. Even New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani allegedly commented on the matter. The contrast between Lynch’s creation and the cheerful, colorful cows painted by children was indeed striking. Lynch’s cow was headless, with a festering wound revealing internal organs, most notably an unnaturally large heart. Scrawled across its side, in what looked like a child’s handwriting, were the words Eat My Fear.

Alongside his work on Hagelin’s campaign, this was perhaps one of Lynch’s most overtly political artistic endeavors. Interestingly, Lynch is not a vegetarian. On the contrary, he has often professed his love for burgers. When asked about the concept behind his cow, he remarked that it’s important to remember where the food on our plates comes from.

Transforming Mulholland Drive: From Pilot to Feature Film

Around the time David Lynch was grappling with New York City’s rejection of his infamous fiberglass cow, he received a call from France. On the other end of the line was Pierre Edelman, an industry contact Lynch had first met during his collaboration with CiBy 2000, the studio behind The Straight Story. Edelman had heard through industry channels about the creation of the Mulholland Drive pilot and asked Lynch to let him view it.

Initially, Lynch was reluctant to send the material to France, as he was dissatisfied with the re-edited version produced for ABC. However, Edelman, who had supported Lynch on multiple occasions during his career, was persuasive. Lynch eventually relented and sent the pilot across the Atlantic. Shortly thereafter, Edelman called back with a proposition: he wanted to purchase the rights to the show from ABC. Backing him was the formidable Canal+, a major French studio involved in producing most films in France at the time. Negotiations with ABC were brief. For the American network, Mulholland Drive was a closed chapter, and selling the rights offered them a chance to recoup at least part of the funds invested in the pilot. For ABC, this was akin to finding a winning lottery ticket. Once the deal was finalized, Canal+ contributed an additional $7 million and tasked Lynch with assembling the cast and crew to shoot new footage. The goal was to transform the existing material into a feature-length film that would not exceed two and a half hours.

Initially, Lynch found this request daunting. The pilot had been conceived as an introduction to a series of plotlines, with their development planned for subsequent episodes. The story was never intended to stand alone as a single film. Compressing the numerous threads into a cohesive narrative while adhering to the strict runtime limit posed a significant challenge. Despite his reservations, Lynch successfully reworked the project. He adapted the original pilot, added new scenes, and wove the story into a feature film that would go on to become Mulholland Drive, a celebrated masterpiece of modern cinema.

Most of the additional scenes were shot in October 2000. After this period, it was time to create the soundtrack and complete the editing. In the first case, Angelo Badalamenti returned to the scene, having already composed unsettling sounds for Lynch using mainly synthesizers for the pilot. When Mulholland Drive became a full-length film, the two men decided that this form of sound design was insufficient. They opted to visit Prague and create a musical score with the local symphony orchestra.

The film’s editing took place in an extremely tense atmosphere, as Lynch was determined to complete it before the Cannes festival’s submission deadline. The director knew that, due to ABC’s actions, it would be difficult to find a distributor for the film in the United States. With the experience gained from previous editions of the festival, Lynch was aware that screening Mulholland Drive at the Grand Théâtre Lumière would significantly increase his chances of finding someone willing to distribute the film in the U.S. After heroic efforts by Mary Sweeney, they managed to deliver the finished material to the festival authorities just a few days before the submission deadline. Mulholland Drive was selected for the main competition alongside twenty-one films chosen from a total of 854 submissions.

Ultimately, Lynch left the French Riviera with the Best Director award, which he shared with the Coen brothers, who were celebrating their success with The Man Who Wasn’t There. The film received very positive reviews. Once again, Roger Ebert, who had previously trashed every Lynch film, came to his defense. The famous critic even made a humorous comment about the director himself. According to Ebert, Lynch’s films are filled with the darkest and strangest creations emerging from the corners of the human psyche. However, when one listens to Lynch the man, it seems like they are in the presence of a true member of a Rotary club.

Ultimately, Lynch left the French Riviera with the Best Director award, which he shared with the Coen brothers, who were celebrating their success with The Man Who Wasn’t There. The film received very positive reviews. Once again, Roger Ebert, who had previously trashed every Lynch film, came to his defense. The famous critic even made a humorous comment about the director himself. According to Ebert, Lynch’s films are filled with the darkest and strangest creations emerging from the corners of the human psyche. However, when one listens to Lynch the man, it seems like they are in the presence of a true member of a Rotary club.

In addition to awards and critical acclaim, the American filmmaker also achieved something he had long desired before finishing the editing of the film—he secured a distributor in the United States. Mulholland Drive was acquired by Universal Pictures. From the director’s perspective, this was a matter of honor. First, Lynch wanted to prove to ABC that the material they had rejected was far more valuable than much of the content they were airing. Second, the filmmaker wanted the audience to receive a complete film, rather than a mutilated version of the pilot circulating in the American black market as illegal bootlegs, often sold in cases originally designed for the cult film Leprechaun (1993) by Mark Jones.

With the release of Mulholland Drive, Lynch once again managed to do what he had achieved in the early 1990s alongside Mark Frost and Laura Palmer, though to a much lesser extent. Thousands of people began to question what they had actually watched. Is Mulholland Drive merely a collection of loosely connected scenes, or is it a cohesive whole? Did the events depicted on screen really happen, or are they just projections of the tortured mind of the protagonist? Mulholland Drive seemingly pulled the viewer into a very similar game, yet the way it was constructed differed enough from Lost Highway that both films stirred extreme emotions in the audience. The first is a riddle with no definitive solution. The plot of the film takes the form of the famous Möbius strip, which, by definition, is non-orientable. The transition between waking and dreaming, imagination and reality, is completely fluid and impossible to pinpoint. Mulholland Drive, on the other hand, operates on different principles. The viewer doesn’t know this immediately, but the difference between the two films is felt subconsciously. Diane Selwyn’s story takes the form of a classic labyrinth, and as a symbolic figure—an archetype deeply rooted in our psyche—it almost automatically draws us into a game, forcing us to search for an exit from the maze of corridors, happily leading us into dead ends. Among the film’s fans, countless theories emerged, each decoding Mulholland Drive in vastly different ways. This is a sign that the labyrinth works.

However, while certain discrepancies in interpretation are entirely justified and arise not from choosing the right path to escape the trap, but from the personal impressions and experiences the viewer brings to their journey through the labyrinth, many analyses of Mulholland Drive try “too hard,” thus falling into the irrational creation of content based on meaningless observations and coincidences. Yet, this is not surprising, as that is exactly how the labyrinth works. When it seems that the light is just on the horizon, and the exit is just around the corner, we find ourselves standing at its beginning once again.

The famous ten Lynchian tips that are meant to help understand the film are not a gimmick, and I don’t say this simply because I fully trust the director’s words, but because their truth is supported by analysis – I emphasize analysis, not interpretation. In the case of Mulholland Drive, what is open to interpretation is not the plot, understood as the progression of the story from point A to point B, but the events and characters involved in the journey between these extreme points. Of course, in the age of Barthesian “death of the author,” no one can stop us from claiming that a barely visible stain on the wall appearing in the fifth scene of the second sequence is a symbolic passage to another dimension from which the monster behind Winkie’s cafe arrives. Sure, go ahead. However, one must ask whether such musings add anything valuable to the discourse surrounding the film. Do they not sometimes function as a double-edged sword in the hands of fans? On one hand, they create the necessary buzz for the film to become part of the broader pop culture; on the other hand, they distract the audience from the more crucial issues within the film, reducing it to something akin to a Rubik’s cube in the hands of a child, where the final goal of solving it matters less than the act of twisting it around.

That Diane Selwyn dreams that Betty is the girl from Winkie’s, and that Rita is Camila Rhodes, is clear. However, the viewer must decide what Lynch is really telling us. It is up to them to understand the enigmatic scene in the Silencio club, to decipher who the Old People are, and to figure out who the figure lurking behind the Winkie’s restaurant is. In these cases, as well as in several or even dozens of others, the matter is entirely open, because analysis itself does not point, and never will point, to definitive answers. On this level, Mulholland Drive is something everyone must personally experience, because each of us is different. One person, turning into a narrow corridor of the labyrinth, will feel fear, another excitement, and yet another will retreat and decide to abandon the journey, escaping the unfriendly space through a deus ex machina triggered by pressing one of the buttons on the remote. However, one thing is certain: during the journey through the dimly lit Mulholland Drive, each of us is alone. During the screening, help is futile to seek.

There’s a reason why this section title includes one of the most famous and perhaps the most poignant lines from Sunset Boulevard. Wilder’s film is, for me, the blue key hidden inside Rita’s purse. It is through this key that I want to read Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. Despite the passing years, the story of Norma Desmond’s downfall has lost none of its power and ferocity. It is probably the most unflinching attack on the American Dream Factory in cinema history. An attack launched not from the periphery, not resorting to guerrilla tactics, but one that takes place at the very heart of Hollywood, and therefore strikes with incredible effectiveness. Mulholland Drive is, in a sense, Sunset Boulevard in reverse. Decades ago, Wilder showed us how the ruthless money-making machine, hidden behind the veil of the dream dreamt by moviegoers, destroys its brightest stars. Half a century later, David Lynch shows us how many stars burn out before we even notice their pale glow.

Cinema is but an illusion that sells us faces, not people.

There are thousands of girls like Diane Selwyn. From childhood, they manage to excel in everything: they win every local dance, acting, and singing competition. Crowds of their peers envy them, while the decent guys are too shy to approach them. They feel that life is open to them, that a great career is within reach. All they need to do is buy a ticket to the City of Angels, drive along the legendary stretch of William Mulholland’s road, and shine in the illuminated streets of movie paradise. Unfortunately, many of them end up behind the counter at Winkie’s bar, others beg for a cigarette from shady characters or seek refuge from human gaze in the dark corners of streets, where, as social outcasts, they continue to dream their dreams of grandeur. In Hollywood, there’s room for everyone.

Diane longed to be like Norma Desmond at the height of her glory, and Norma, though she couldn’t know Diane, would certainly have swapped places with her to be young again, full of vitality, and attractive to the unrelenting eye of the camera. It is at this point that the paradox of Hollywood is highlighted, where there are essentially no winners. There are only those who have money. As long as anyone wants to watch the show in which we take the lead role, everything is fine. But eventually, the moment must come when the phones fall silent. Then, like Rebekah Del Rio, we will collapse on the stage of the Silencio club, but that doesn’t mean the show is over. The music keeps playing because Hollywood is just a dream, a show played from a tape. Cinema is but an illusion that sells us faces, not people. Sometimes we painfully learn this—when an actor who entertained an entire generation decides to take his own life, or when, in front of his family, a man who portrayed Alvin Straight, teaching us to fight until the very end, shoots himself in the head. Then, following the lament from the Silencio club, all we can do is cry. Unfortunately, for Diane and many others, by then it is too late.