THE STRAIGHT STORY: a Prayer. Lynch’s Masterpiece Explained

The Elephant Man propelled the director beyond the smoky halls of late-night cinemas where Eraserhead had been shown for years, but it wasn’t until Twin Peaks that Lynch’s cinema became a pop-cultural phenomenon.

However, the last decade of the 20th century was not an uninterrupted string of successes for the American filmmaker. The pale body of Laura Palmer, washed up on the shore of a foggy small town, electrified millions of viewers worldwide. But not all of them were ready to stay rooted in Lynch‘s world for longer than a few episodes of the series. Fire Walk With Me was met with a very cold reception from both audiences and critics. Financial failure also struck Lost Highway. Despite a favorable contract, the studio CiBy 2000 blocked the director’s eccentric projects, fearing they would bring even more severe losses. Thus, the creator, who at the beginning of the 1990s had won the Palme d’Or for Wild at Heart and graced the covers of prestigious magazines due to Twin Peaks, found himself once again in a rather complicated situation. The Straight Story

Painting became a refuge from the problems of film financing and the widespread accusations of senseless violence and misogyny. A great support for him was also his relationship with Mary Sweeney, who slowly introduced Lynch to her childhood world, deeply connected with growing up in the Great Lakes region. Her hometown, Madison, Wisconsin, initially didn’t seem interesting to the director, but with each visit, he warmed up to both the place and its people. After the buzz surrounding the premiere of Lost Highway had died down, Lynch agreed to an artistic collaboration with Tandem Press, an atelier under the auspices of the local university. As part of this, he created a series of lithographs, which were then auctioned in Chicago and New York, fetching substantial sums. However, it was not graphics or painting that would permanently link Lynch’s creative life with Wisconsin. Madison, once the backdrop for one of the director’s favorite films, Werner Herzog’s Stroszek, did not secure a place in his cinematic world either. He missed it by just over a hundred kilometers, as that’s roughly the distance separating it from Blue River, a small settlement now home to about four hundred people. It was there, in the summer of 1994, that Alvin Straight, the protagonist of The Straight Story, ended his extraordinary journey.

On August 24, 1996, a short article titled Brotherly Love Powers a Lawn Mower Trek appeared in The New York Times. Had it not been for this text, it’s likely that no one would have heard about the seventy-three-year-old Iowa resident who, having lost his driver’s license due to vision problems, decided to set off to reconcile with his brother on a 1966 John Deere lawnmower. By chance, the August issue of The New York Times also fell into the hands of Mary Sweeney, who, due to her background, was very familiar with the regions Straight had traversed. The man’s determination to reconcile with his brother on his own terms reminded her of people long gone from her life. It was a symbolic story about a world that once seemed like the only one to her.

A few days after reading the article, Sweeney sought to secure the film rights, only to find out that she wasn’t the only one who saw the potential in Straight’s story. An American studio had almost immediately purchased the rights to the New York Times piece. The script was to be written by Larry Gelbart, known mainly for the TV version of *M*A*S*H*, and the role of Alvin was reportedly reserved for Hollywood veteran Paul Newman. Sweeney, however, didn’t give up and closely followed the direction the project was taking. When the rights reappeared on the market in February 1998, Sweeney promptly acquired them. Although she had spent almost her entire adult life working as an editor, she decided to write the script herself due to her personal connection to Straight’s story. She enlisted the help of her childhood friend John Roach, who, like her, fully understood why she was determined to bring the story to the screen.

The research for the script and the writing process wrapped up very quickly. Unfortunately, the authors didn’t have the chance to meet Straight in person, as he had passed away two years after his journey (on November 9, 1996). The script was completed in June 1998 and almost immediately landed on Lynch’s desk, who at first adamantly refused to read it, fearing that he wouldn’t be able to give it a positive review, and thus, would hurt Sweeney, who had invested so much energy and passion into it. Lynch wasn’t comfortable being a reviewer, and Straight’s story wasn’t intriguing enough for him to consider directing it. Sweeney recalls that when she left the script on her husband’s desk, she never imagined he would ultimately decide to direct the film. However, after reading the script, Lynch had no doubts. After the labyrinthine Lost Highway, it was time to tell The Straight Story.

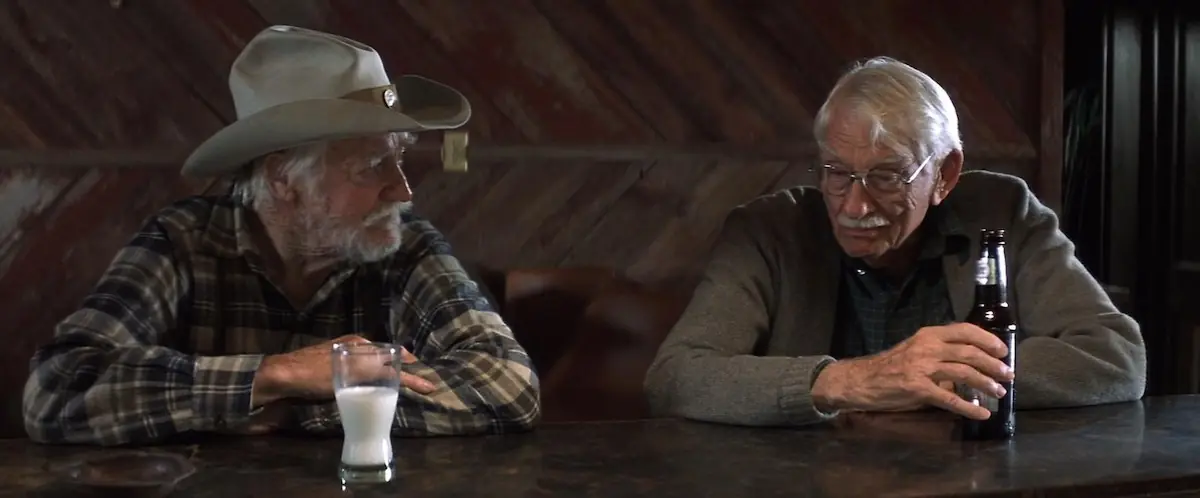

At first, the director saw Gregory Peck in the role of Alvin. The actor, who hadn’t appeared in a film since 1993, didn’t agree to return to the screen. The next choice was John Hurt, who had portrayed The Elephant Man a decade earlier. Unfortunately, they couldn’t reach an agreement in that case either. That’s when Richard Farnsworth’s name came into the picture. A cowboy, stuntman, and supporting actor who got his start on the sets of films like Gone with the Wind, Farnsworth was perfectly suited for the role. If Alvin Straight were alive, Farnsworth would have been his peer. The men shared similar experiences, growing up, aging, and living in the same America. After meeting Farnsworth, Lynch knew he didn’t want anyone else in the role. However, a problem quickly arose. The actor decided to turn Lynch down due to his health condition. He had been diagnosed with terminal prostate cancer, which had started to spread to his bones. Farnsworth could barely walk, needing two canes for support, and had further worsened his condition during a fall on the farm, injuring his hip. Lynch assured Farnsworth that moving with two canes wouldn’t be an issue for the character, so he needn’t worry about it affecting the work on set, which was Farnsworth’s main concern. Additionally, the director promised that once Farnsworth accepted the role, the seat of the John Deere mower he would be riding for much of the film would be specially contoured to alleviate the pain caused by his hip condition. The actor agreed to these terms.

Besides Farnsworth, the set of The Straight Story also included longtime members of Lynch’s film family. Cinematography was handled by Freddie Francis, who had worked with the director on The Elephant Man and Dune. The role of Straight’s daughter was played by Sissy Spacek, one of Lynch’s closest friends, while the sound was managed by her husband, Jack Fisk, who had also been part of Lynch’s world for ages. The soundtrack, of course, was composed by Angelo Badalamenti. The production was undertaken by Lynch’s studio Picture Factory, Sweeney, and Neal Edelstein, along with the French company Studio Canal. Nine million dollars were gathered for the film’s production.

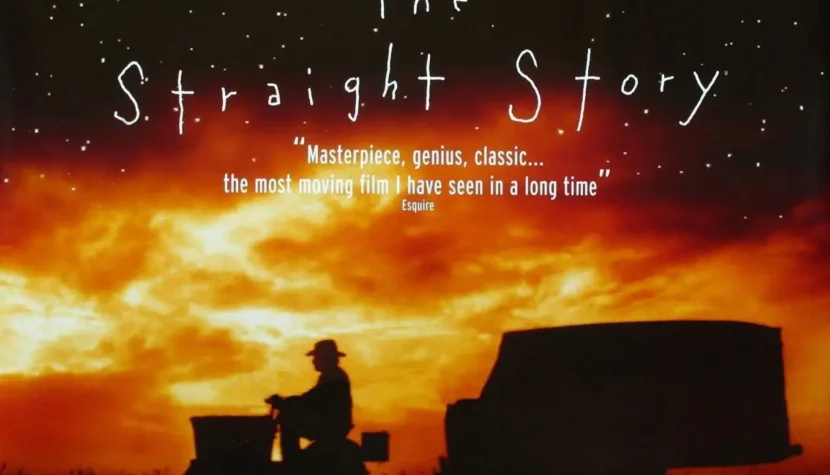

When The Straight Story was screened at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1999, even Lynch’s harshest critic, Roger Ebert, gave it the highest possible rating. Since The Elephant Man, no other Lynch film had been met with such universally positive reception from critics and audiences alike. Considering that two years earlier Lynch had attended the festival with Lost Highway, and before that won it with Wild at Heart, the fact that through business negotiations in the corridors of Cannes, The Straight Story ended up under Walt Disney’s wing astonished the media. The director, who had recently faced a storm of criticism over violence and the objectification of women, was now distributing his new film under a studio synonymous with childhood innocence and aversion to violence and sex. What’s more, Disney representatives mentioned in interviews that after watching The Straight Story, they were open to further collaboration with Lynch. Hell had frozen over.

A Prayer

A few years after the release of The Straight Story, Mary Sweeney mentioned in an interview that she was extremely proud of her screenplay. Nevertheless, she believed that David elevated the film to a completely different level, turning the story into something akin to a prayer. Somewhere amidst Francis’ warm shots, Badalamenti’s music, and Farnsworth’s determined and contemplative face, there truly is something that gives this story an extraordinary dimension. Throwing around words like “sacred” or “metaphysical” almost always feels a bit amusing and rather cheap, because how can we compare a story about a man traveling on a lawnmower to philosophical tomes discussing the nature of being? This is not the same language, not the same categories. And yet, every time I watch The Straight Story, I am convinced that its simplicity is only superficial, because in the series of smiles and grimaces of pain on Farnsworth’s face, amidst the landscapes of Iowa and Wisconsin, among the small gestures of human kindness shown by those who cross Straight’s path, and ultimately in that final gaze at the stars, there is no less meaning than in hundreds of pages of philosophical debates. That is precisely why I appreciate the ambiguity of the English title, where the word “Straight” refers both to simplicity and to the main character’s last name. In this light, we can have both a straight story and Straight’s story, which may not be so simple after all.

It’s hard to write about The Straight Story because most of the important things happen without words or between the words. Verbal minimalism is the main strength of Sweeney and Roach’s screenplay. This film could easily have been overtalked, ruined by stuffing it with lofty phrases about human resilience, love, and perseverance. Fortunately, that didn’t happen. Most of the dialogue doesn’t even talk about the characters’ feelings or motivations. From brief information, the viewer has to figure out on their own what emotions drive the characters. And it’s not just about Straight, but also about the people he meets—especially the family on whose yard he camps—and his daughter, who has missed her children for almost her entire adult life. That’s one reason why I don’t particularly like the official poster for the film, which focuses on the lawnmower journey but forgets about the people.

The journey here is merely a pretext for reflecting on human life—no matter how banal that may sound and how strongly the metaphor of the road has already been exploited. This is a film about life, about Sweeney trying to breathe part of her world into the borderlands of Wisconsin and Iowa. It’s the story of Straight, who at the end of his life decided to reconcile with his brother and set out on a journey, just as he did in his youth when he slowly traversed America selling horses. It’s the story of Farnsworth, who, after years of wrangling with horses and performing stunts, must now battle his own body, which is refusing to cooperate and causing him almost unbearable pain. In the end, The Straight Story is a universal tale about each of us. The story of a human is simple: it has a beginning, a journey, and an end. But everyone knows that this simplicity is only an illusion.

Alvin Straight died on November 9, 1996. Richard Farnsworth passed away on October 6, 2000. The actor had enough of the pain caused by his spreading cancer. He took his own life. Lynch’s film was his swan song and the greatest achievement of his long acting career. In this context, the final line, You rode that thing all the way out here just to see me? and Straight’s brief reply, “Yep,” take on special significance. The sky and stars, which Alvin and his brother gaze at through tear-filled eyes, and which Lynch himself often looks to for solace for his characters, can symbolize a better world. However, in the American’s vision, this world does not exist apart from the individual. It is through another person that one can find peace and consolation, can reach those metaphorical stars that the Straights, Henry Spencer from Eraserhead, or John Merrick from The Elephant Man gaze upon. The individual is the most important. Always.