TWIN PEAKS, Season II and FIRE WALK WITH ME Deciphered

In the early 1990s, the director was literally everywhere. His face gazed at readers from the covers of prestigious magazines, including the American The Times, which in October 1990 dedicated a large article to him titled The Wild-at-Art Genius – Behind Twin Peaks. Industrial Symphony No. 1 – The Dream of the Broken Heart, the first and also last play directed and produced by Lynch, was staged at one of America’s most prestigious theaters. The music created for the series and its continuation, which appeared on the solo album Into the Night, made Julee Cruise a performer filling concert halls. Lynch received dozens of commercial offers, carefully selecting the most interesting ones. From his hands came advertising campaigns for brands like Yves Saint Laurent, Calvin Klein, and Giorgio Armani (commercials for perfumes produced by the fashion industry titans). Lynch also created video material promoting Michael Jackson’s Dangerous tour.

A separate issue was his status in Japan, where Twin Peaks became a national obsession. Lynch became the biggest American star in Japan, which did not go unnoticed by the series’ producers. Many advertising campaigns were made for Japanese television, including a series of commercials set in the Twin Peaks TV town, directed by Lynch, promoting Japan’s most popular coffee. These marketing strategies were fully understandable, considering the fact that Sheryl Lee (who played Laura Palmer) recalled witnessing a symbolic funeral for her character during a promotional visit to Japan. The attendees wept and cried as a coffin with a lifelike doll of Laura Palmer, wrapped in the iconic plastic bag from the series’ prologue, was buried. The world can be crazier than even David Lynch’s wildest visions.

However, Lynch’s popularity acted like a double-edged sword. As the pulse of enthusiasts for his work increased, so did the dissatisfaction of those who didn’t see him as a small-town American directorial genius. Moreover, the immense success of Twin Peaks attracted an audience that was definitely not ready for what Lynch had to offer, leading to some friction when these TV viewers encountered certain elements of the director’s cinematic productions. Even before the American premiere of Wild at Heart, there was a controversy about the film’s age rating. If the distributors decided to release the European version shown at Cannes, it risked being given an X rating, which at the time was a stricter version of the popular R-rating. This would have meant that viewers under the age of 17 could not see the film, even with adult supervision. This restriction posed a threat to the film’s financial results, so Lynch was forced by producers to adapt the film for the American market. As a result, a scene in which Bobby Peru blows his head off was “censored” with a cloud of smoke from the shotgun covering his head’s dramatic flight. This, despite many other censorial objections, was enough to secure an R-rating for the film. Ultimately, Wild at Heart grossed over $14.5 million in the U.S., which, given the type of production and its budget hovering around $10 million, was a fairly decent result.

In the context of Wild at Heart, accusations also began to surface against Lynch that had been quietly voiced after the release of Blue Velvet in 1986. Critics accused him of promoting extreme misogyny, culminating in the scene of Bobby Peru’s emotional rape of Lula, left in the small town of Big Tuna. To support their arguments, critics listed elements of Lynch’s work that depicted the abuse or exploitation of women. Dorothy Vallens being tormented by the demonic Frank came back into the spotlight, and it was pointed out that Twin Peaks largely revolved around the persecution and murder of an underage girl. After the prologue of Wild at Heart, accusations of racism also arose. It was noted that the criminal subdued by Sailor, who threatens him and Lula with a knife, was Black, which was seen as reinforcing negative stereotypes about African Americans. Things were happening.

Who killed Laura Palmer?

While creating the first season of Twin Peaks, Mark Frost and David Lynch were uncertain whether ABC would want them to return to the set for a second season. To optimize their chances, they ended the eighth episode of the series with a typical cliffhanger, which could potentially electrify the audience and, in case of moderate enthusiasm for the production, convince producers to fund at least a few more episodes. It turned out that shooting Cooper in the eighth episode wasn’t necessary to get ABC’s green light and the funds needed to produce the second season. People still wanted to know who killed Laura Palmer, and television producers couldn’t ignore this demand.

Unfortunately, the famous question about the identity of the murderer of the most popular student attending the high school in the forest-surrounded town of Twin Peaks became a curse for the series. The average American consumer wasn’t used to waiting so long for the resolution of a crime mystery. ABC began pressuring the creators more and more, demanding they finally reveal to the viewers who was responsible for Laura Palmer’s death. Their claims were supported by the series’ declining viewership compared to the first season. In a way, the network was right. Many casual viewers, who had come across the first episode of Twin Peaks and decided to stay in that world to discover the solution to the mystery of the body washed ashore in a dirty plastic bag, started turning away from the series because it was significantly different from what could be seen on American television at the time. Many people likely felt deceived, or even manipulated, by Frost and Lynch, who consistently delayed revealing the mystery. For a large part of the audience, it was seen as a cunning game meant to stretch the series as much as possible to accommodate the largest number of commercial breaks. ABC, which charged hefty fees for these breaks, didn’t like the drop in viewers, so they decided that solving the mystery—and, as a result, pushing the plot of the series forward—was necessary to re-energize the audience and encourage them to follow the characters’ fates. However, this was the wrong approach.

The creators ultimately gave in, and in the seventh episode of the second season, the 15th episode of the series overall, the world learned that Laura Palmer’s murderer was her father, Leland. The airdate of this episode, November 10, 1990, can be seen as the symbolic beginning of Twin Peaks’ downfall. ABC indeed got its way and achieved short-term success because the episode Lonely Souls, written by Mark Frost and directed by David Lynch, attracted over 17 million viewers—six million more than the previous episode, a figure comparable to the episodes from the first season. While it initially seemed that revealing the identity of the killer was a smart move and that the newly gained audience would stay with Twin Peaks for the long haul, it quickly became apparent that the series wasn’t ready for such a resolution. In hindsight, Lynch claims that giving in to the network’s pressure was one of the biggest mistakes of his career. Frost, who during the production of the second season was essentially the main coordinator of both the script and the on-set activities, has also repeatedly mentioned the disastrous effects of that decision.

After Leland’s unmasking, Twin Peaks hit a dead end. Lynch, who had distanced himself from the series earlier (mainly due to his work on Wild at Heart), withdrew from it entirely. He did not return to the set as a director or screenwriter until the final episode, in which he was responsible for creating the surreal ending and the famous cliffhanger that closed the second season. Even worse, Mark Frost also significantly distanced himself from the project, as he got the opportunity to make his own feature film, Storyville.

After the 15th episode, the series began to decline significantly in quality. Despite the fact that audiences, through dozens of letters sent to the creators, demanded that the rest of the series focus on the relationship between Audrey and Cooper, the creators decided not to take that route. The ultimate argument in this matter was apparently Kyle MacLachlan’s opinion (Cooper’s actor), who stated that his character would never allow himself to have a romance with a high school girl. There’s a lot of truth in that statement, but it didn’t stop the speculation about the abrupt ending of the potential romance between the FBI agent and the student. Many attributed this development to Lara Flynn Boyle, MacLachlan’s partner during the second season. The actress was supposedly pathologically jealous of Sherilyn Fenn, who played Audrey, so any love scenes or bedroom scenes were out of the question at the time. Frost jokingly says he regrets not putting into the script that Audrey had repeated a grade several times, making a romance with Cooper more plausible and a good foundation for the rest of the series. The odd cessation of this storyline led to the introduction of Annie, who became the object of Cooper’s affection. Frost saw this move as a clear mistake, believing that a character introduced so late couldn’t win over the audience’s favor. The lack of clear ideas for the plot’s development led to the over-exploitation of side threads, which over time became less coherent and, in Frost’s view, caused the character Windom Earle to appear too early. Earle, who was supposed to be a villain in the final episodes, became a long-running character whose plotline dragged out, diluting its impact. David Lynch was also unhappy with this, emphasizing that Earle was a character created solely by Frost. Nonetheless, after the 15th episode (with the exception of the season finale), Lynch decided not to interfere with the script as he was dissatisfied with the direction the series was taking (partly due to ABC’s pressure).

The final blow to Twin Peaks came with changes to the network’s schedule and attempts to cancel the series before the second season ended. Moving the show’s airtime to 10 p.m. on Saturdays caused the loss of more viewers, who preferred other activities on Saturday nights rather than sitting in front of the TV. This drop in viewership prompted ABC to abandon the series. Fan intervention allowed for the production of a few more episodes, which aired late on Monday nights. In May 1991, the network officially announced that Twin Peaks would be taken off the air, and a third season was not in the plans. Two final episodes were aired in June, and Lynch left his mark on the finale once again.

Fire Walk with Me

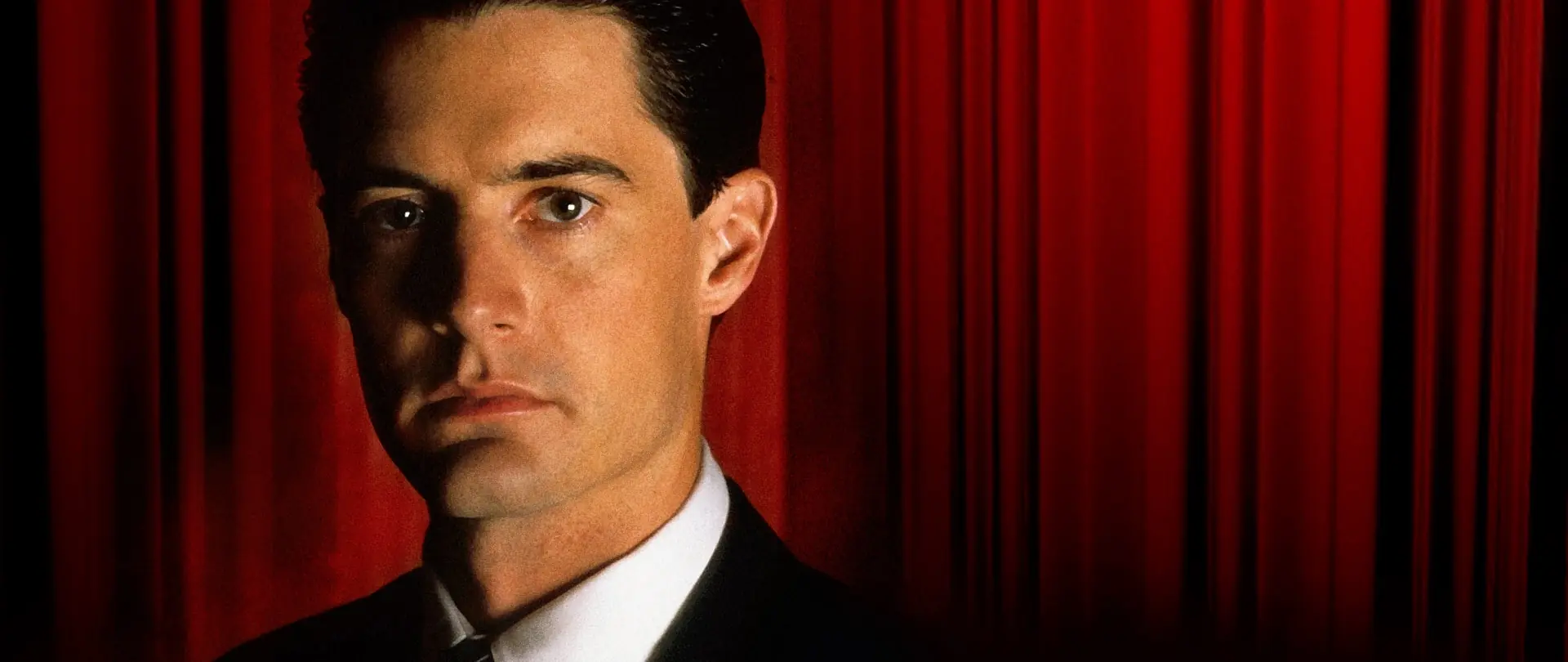

When Agent Cooper hit his head on a mirror, blood trickled from his forehead, his mouth twisted into a terrifying smile, and his reflection turned into BOB, the show’s embodiment of evil and the darkest secrets hidden in the woods surrounding Twin Peaks, viewers who had made it to the second season’s finale were left stunned. ABC clearly stated that this was the end of the series, yet the creators left the audience with many unresolved mysteries and a cliffhanger that made Cooper’s shooting in the eighth episode seem like a minor event. This situation would not change, however. The television adventure of Twin Peaks came to an end, although now we know that the prophecy uttered by Laura Palmer in the Red Room turned out to be true, and the series would return to viewers in 2017 (in a highly surreal vision, Laura told Cooper in 1991 that they would meet again in 25 years).

Lynch wasn’t willing to accept that his journey in Twin Peaks had ended this way. Partly consumed by guilt over distancing himself from the second season’s production and partly due to his strong attachment to the characters and the fictional town, Lynch wanted the dream of Douglas firs, owls, and the mysteries hidden among the trees to continue. A television continuation of the series was out of the question, so the idea of making a feature film arose. Initially, before the final episode aired, none of the producers would have been interested in delving into a world that, according to ABC’s ratings, no longer fascinated viewers. However, after the series finale, a new opportunity arose, making the idea of a feature film more attractive. In 1991, Lynch signed a deal with CiBy 2000, a studio founded a year earlier by the well-known, though not widely liked, French producer Francis Bouygues. The deal was worth 70 million dollars and stated that Lynch would make his next three films under the studio’s banner. Initially, the first project was going to be Ronnie Rocket (a recurring idea in Lynch’s career), which was allocated 25 million dollars from the budget, followed by One Saliva Bubble, with a third, undefined project in the pipeline. When Lynch made it clear that he wanted to return to the world of Twin Peaks, the plans quickly changed. Ronnie Rocket and One Saliva Bubble were shelved again. CiBy expressed interest in a feature film based on the series, although in the early stages of production, a problem arose with Kyle MacLachlan, who strongly opposed reprising his role as Agent Cooper. For this reason, it was announced on July 11, 1991, that Fire Walk with Me would not be made. However, Lynch didn’t give up and reached a compromise with the actor. By significantly reducing Cooper’s role and transferring part of his duties to another FBI agent, MacLachlan agreed to appear in the film. Thanks to Lynch’s changes, MacLachlan spent only five days on set. However, other cast members from the series did not return to Twin Peaks.