UNIVERSAL PICTURES. The History Of The Legendary Film Studio

Before reaching the age of eighteen, however, he decided that, like his older brother and many young men who were seeking their place in the world at the time, he would leave his family home to try his luck in the legendary America.

At the end of 1884, Laemmle settled permanently in Chicago, where he married Recha Stern. Shortly after, their first child, Carl Laemmle Jr., was born. In 1889, the German immigrant was able to obtain an American passport. His dream of the United States was gradually taking shape. Of course, the start wasn’t easy. Laemmle took on various jobs to make ends meet, although even at the beginning of his career, he showed skills in capital management and accounting. He began working in this field in 1894, starting his collaboration with Continental Clothing Company. Managing the clothing company’s capital provided him with financial stability, but it didn’t satisfy his ambitions to create a business from scratch. Laemmle was still looking for opportunities to wisely invest the capital he had accumulated over the years and multiply it in a way that would make him fabulously wealthy. It’s hard to say whether it was through a deep analysis of the market or simply by chance, but at the beginning of the 20th century, he turned his attention to film. In 1906, Laemmle left his lucrative position and became the owner of one of the first movie theaters in Chicago. His business experience, however, suggested that the company’s operations should not be limited to a specific, narrowly defined activity. From the very beginning of his independent venture, Laemmle thought about creating a network of services that could complement each other. This idea became the foundation of Universal Pictures.

The driving force for the immigrant was the policy pursued by Thomas Edison, the absolute giant of the early American film industry. The well-known inventor was also an exceptionally successful businessman who quickly understood the commercial potential of cinema. Edison not only patented various devices used by the nascent film industry but, starting in 1908, he controlled the Motion Picture Patents Company, also known as the Edison Trust. This organization was a monopolistic agreement between the significant studios operating in the American market at the time. It limited the influx of foreign productions and sought to modify the system by which films made in the United States were distributed. Edison wanted to move away from a model in which the rights to a finished film were sold to distributors managing movie theater chains. Instead, he wished to introduce a rental system that would allow the Motion Picture Patents Company to maintain almost complete control over the films it created, while forcing theater owners to pay ongoing fees to the organization. Laemmle, who owned several theaters when the Edison Trust was formed, did not want to accept becoming just a small cog in the large machine under the dictatorship of one person. The only way to free himself from Edison’s control was to produce his own films.

In 1909, Laemmle, along with his brothers-in-law Abe and Julius Stern, founded the Yankee Film Company, which almost immediately evolved into the Independent Moving Pictures company, a small studio independent of the Motion Picture Patents Company’s influence. The company had offices in New York and New Jersey, where its films were also shot. Between 1910 and 1912, Laemmle’s venture gained momentum. Under the name Motion Picture Distributing and Sales Company, the company created more than two thousand films over two years, which, of course, caught the attention of Edison, who sought to curtail and ultimately completely outlaw the activities of independent film studios. Since the inventor held patents for most of the film equipment used in the United States, and small studios, in order to bypass this obstacle, often used unlicensed equipment imported from Europe or, without making it too obvious, also used Edison’s equipment, the monopolist often sued them for using equipment that did not meet the standards or violated the patents associated with it. Laemmle also found himself on the list of those sued, but the court ruled in his favor.

On April 30, 1912, the Universal Film Manufacturing Company was founded in New York, absorbing the Motion Picture Distributing and Sales Company previously managed by Laemmle. Among the studio’s founders were Mark Dintenfass, Charles O. Baumann, Adam Kessel, Pat Powers, William Swanson, David Horsley, and Jules Brulatour. However, it didn’t take long for the German immigrant to buy out the shares of the co-founders, making him the sole legitimate owner of Universal. The new venture was self-sufficient, producing and distributing films independently, and owning its own network of movie theaters, free from the influence of the Edison Trust. In March 1915, Universal City Studios was established near Hollywood, becoming the largest production center in the world for the next decade. It covered an area of nearly one square kilometer and was the first to open its doors to tourists, who were not allowed access to facilities managed by other Hollywood studios. This openness to the public was, in fact, a hallmark of Laemmle’s policy. Since 1909, when he made his first films, Laemmle, unlike Edison, promoted films by the names of the actors and filmmakers involved, thereby contributing to the creation of the star system, which would flourish in the American market a decade later.

Despite the scale of Universal’s venture, the company for many years hesitated to take on the first-tier players in Hollywood. A significant portion of the films produced by Laemmle’s company was aimed at audiences living outside major cities—those visiting smaller, lesser-known theaters rather than the glitzy multiplexes where famous personalities were often spotted. Universal’s system involved producing three types of films. The majority were low-budget films categorized as Red Feathers. Next in line were Bluebirds, which were mid-range films. The rarest productions were the high-budget premium films, known as Jewels. This approach was directly tied to Laemmle’s own philosophy, which involved avoiding the risks associated with financing via loans. The absence of borrowing meant that Laemmle didn’t face the threat of losing his company if a high-budget production failed financially. However, it was also one of the main reasons for Universal’s stagnation and its vulnerability to other Hollywood players. This policy didn’t, however, guarantee complete safety, as shown by the situation during the production of two films by the rebellious Erich von Stroheim – Blind Husbands (1919) and Foolish Wives (1922). The ever-growing budgets of these films almost drove Laemmle to bankruptcy, but his experience and creative marketing skills allowed him to successfully promote the films and recoup the money invested.

The productions that solidified Universal’s position in the market were two films starring Lon Chaney, which began the iconic Universal Monsters/Universal Horrors franchise, a series of horror films created by the studio between 1923 and 1960. The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) and The Phantom of the Opera (1925) were commercial hits, largely due to the involvement of the young producer Irving Thalberg, whom Laemmle had brought into the company. Despite his youth, Thalberg had earned a reputation as a wunderkind in the industry after just a few years of working in film. Impressed by his talents, Laemmle made him head of production at the studio when Thalberg was just under 25 years old. However, such recognition was not enough to contain his extraordinary talent. By the age of 26, Thalberg was still head of production, but at the competing Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, which was able to offer him a much higher salary. His departure had a significant impact on Universal, which struggled to capitalize on the success of the Chaney films and continued to operate as a less significant studio, unable to build on the momentum and climb to the top.

The lack of prospects for breaking into the American major leagues led Laemmle to turn his attention to his home continent. In 1926, Universal opened a branch in Germany (Deutsche Universal-Film AG), headed by Joe Pasternak. The films produced in Europe were primarily in German, with occasional productions in the languages of the countries that would become their target markets (mainly Hungary and Poland). Unfortunately, due to the political situation arising from the rise of the Nazi party, and the resulting hostility from the authorities toward foreign capital, Deutsche Universal-Film AG was doomed to failure. In 1936, the branch was closed, and Pasternak emigrated to the United States, where he successfully transplanted some of the conventions of the films made in Europe. The most popular genre was the musical, featuring young girls singing in soprano. Penny (1936) starring Deanna Durbin, the first such film produced by Pasternak in America, became a commercial success, helping to pull the studio out of a serious financial slump caused by the production of The Great McGinty (1936).

In 1928, Carl Laemmle Jr., the son of the founder, formally became the director of Universal. His succession to the role did not surprise anyone in the industry, as nepotism had long been a characteristic of the studio’s leadership. It was said that among Universal’s employees, Laemmle was affectionately known as “Uncle Carl,” a nickname that seemed fitting given that around seventy members of his family were reportedly employed by the company at the time. It is also worth noting that one of the people who entered the world of cinema thanks to his influential relative was William Wyler, regarded as one of the most important directors of Hollywood’s Golden Age. The founder’s family-oriented approach even prompted a comment from American poet Frederic Ogden Nash, who humorously satirized it in a short rhyme: “Uncle Carl Laemmle / Has a very large faemmle” (playing with the word “family” to make it sound like “faemmle,” reminiscent of Laemmle’s last name).

From the outset of his career, Carl Jr. aimed to modernize the studio, which naturally required significant investment. Universal began purchasing existing theaters and constructing new ones. The studio also started producing sound films and returned to making films in the Universal Horror genre, which had once brought it enormous popularity. In the early 1930s, iconic films such as Frankenstein (1931), Dracula (1932), The Mummy (1932), and The Invisible Man (1933) were created, cementing the fame of Bela Lugosi, Tod Browning, and James Whale. All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) earned the studio its first Academy Award. It seemed that everything was finally moving in the right direction, and that it would only take a few seasons for Universal to join the ranks of the major American film studios. However, Carl Jr.’s aggressive policies could not align with the principles of his father. Universal could not afford to cover all the ventures approved by its new head. While the steps Carl Jr. took were not wrong, they were made at a time when most companies were being cautious with every penny, preferring a safe stagnation rather than comprehensive modernization. We must also remember that between 1929 and 1933, when Carl Jr. began to implement his new vision for the studio, the world was grappling with the Great Depression. Aggressive capital investment and depleting financial reserves were, to say the least, not the safest actions during such times. This approach negatively impacted not only the studio but also the Laemmle family itself.

The film that led to the Laemmle family’s loss of influence over the studio, which had belonged to them since its founding, was the previously mentioned Show Boat from 1936. The title could be considered “cursed” for the Laemmle family, as a previous version of the story, produced by the studio a few years earlier, also proved to be a financial failure. This time, in line with Carl Jr.’s temperament, the film was meant to be more than just a low-budget production for local theaters; it was to be a first-class musical. Well-known Broadway actors were hired, and a large sum of money was invested in the set design and crew. Carl Jr.’s free-spending approach did not go unnoticed by the studio’s financial backers. Attempts were made to halt the production. To finish the musical, Universal had to take out a loan for the first time in its history. The company borrowed $750,000 from Standard Capital Corporation, which required control over the studio as collateral for the loan. Show Boat exceeded its budget by more than $300,000, and Universal was unable to repay the debt. The Laemmle family was forced to step aside, even though Show Boat eventually turned out to be a significant financial success. Control of the studio was taken over by Standard Capital Corporation, and John Cheever Cowdin was appointed president. He abandoned Carl Jr.’s policies, cut company expenses, and focused on producing smaller films, which had always been the foundation of Universal’s business.

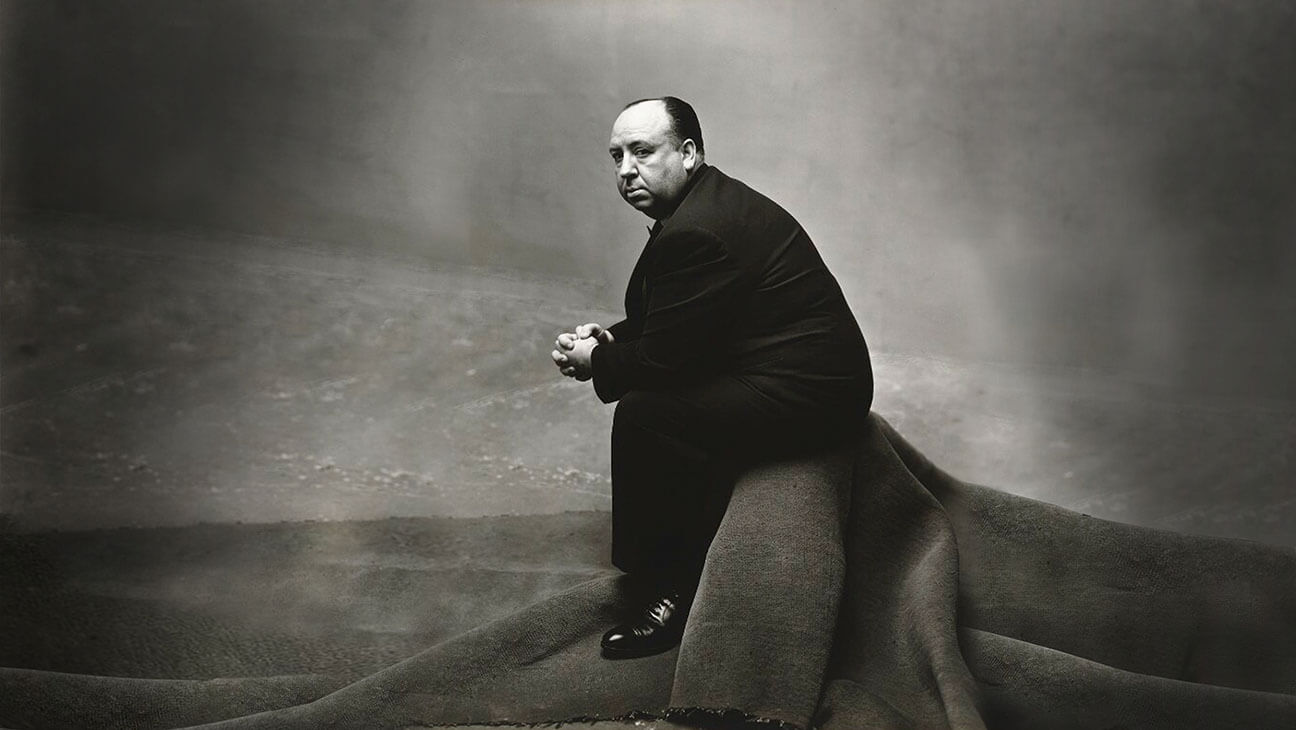

Throughout the 1940s, Universal focused on producing films with small or medium budgets. Much like during Carl Jr.’s time, the primary audience for these productions consisted of people from small towns and villages, frequenting low-class theaters. The studio’s “small-town” imprint is particularly evident when looking at its Oscar history. Although Universal’s films were nominated over the years, from the first Oscar win in 1930 for All Quiet on the Western Front to the Oscar win for The Sting in 1973, the studio did not receive an award in the most prestigious category—Best Picture—during this entire period. Despite Carl Laemmle’s early contributions to the creation of the famous American star system during Hollywood’s Golden Age, the studio could not afford to keep big-name stars on exclusive contracts. The most famous actors associated with Universal during this time were Margaret Sullavan and Bing Crosby. Other major stars appeared with the studio occasionally, under contracts signed with other film companies. For example, Alfred Hitchcock directed films for Universal, including Saboteur and Shadow of a Doubt.

Changes came in the late 1940s when British financial magnate Joseph Arthur Rank took an interest in Universal. Although his initial plan to merge Universal with Rank Organisation, the independent studio International Pictures (created by William Goetz), and the interests of influential producer Kenneth Young did not succeed, Rank and Goetz remained interested in Universal after a year of business operations. This led to another reorganization of the American studio, resulting in the formation of Universal International Pictures, with William Goetz at the helm. Goetz was no amateur—his career in the film industry dated back to its early days in the 1910s. Over his turbulent career, he managed United Artists, founded Twentieth Century Pictures (which later evolved into 20th Century Fox), and served as vice president at the studio.

Such a resume raised hopes that Universal would finally climb out of its slump, but once again, it didn’t succeed. Goetz, not for the first time, wanted to break free from the small-town stigma of the studio and begin its expansion into areas previously reserved for the bigger players. The first step toward this goal was, of course, a close collaboration with Rank Organisation, which included securing exclusive rights to distribute British films produced by the studio in the United States. Under this agreement, classics such as Great Expectations by David Lean and Hamlet by Laurence Olivier premiered in America. The acquisition of Castle Films, one of the largest companies involved in the burgeoning home video market, was intended to expand Universal’s presence in that area, but Goetz’s investment failed to bring the expected profits. Despite a few hits like The Killers (1946) by Robert Siodmak, Universal continued to face financial troubles, which displeased Joseph Arthur Rank, who decided to withdraw from the business and sell his shares to Milton Rackmil and his Decca Records. This move once again curtailed Universal’s ambitious plans and returned the studio to making modest productions for a less demanding audience.

Under the leadership of Decca Records, Universal sank deeper into despair. The studio’s films no longer appeared among the nominees for any prestigious awards. The brand’s logo increasingly failed to attract major names to the set. By the late 1950s, when the model based on the close connection between film studios and cinema chains collapsed, Universal was virtually on its knees. The people at Decca Records couldn’t keep up with the times and missed the opportunity that arose with the rapid development of television and the decreasing role of cinemas in the film industry. However, another company, the Music Corporation of America (MCA), seized its chance. In 1958, Universal, which had suspended its operations for some time, sold its production village, covering one and a half square kilometers, to MCA for eleven million dollars. Although Universal formally only sold the property, not the studio itself, MCA’s involvement increasingly influenced the company’s activities.

MCA’s clients, such as Cary Grant and Alfred Hitchcock, began signing contracts with Universal, signaling the imminent takeover of the studio by MCA. After a thorough modernization of the company managed by Decca Records, the merger was finalized. In 1962, the companies merged under the name Universal Pictures. In 1964, Universal City Studios was created, combining the film and television divisions of Universal Pictures and Revue Productions. With the completion of the acquisition by MCA, Universal finally became a major player not only in the American market but also in the global film production industry, breaking the small-town curse that had haunted it since the days of Carl Laemmle’s leadership.

The studio’s journey to the red carpets, however, was not an automatic process, as throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Universal focused mainly on the television market, including close cooperation with American NBC. Of course, among its productions were titles distributed in cinemas that achieved significant commercial and critical success, yet their creation was not the core of the company’s operations. The most famous films from this period include The Sting (1973), American Graffiti (1973), and its biggest financial success, the iconic Jaws (1975) by Steven Spielberg. It wasn’t until the 1980s that a turning point occurred, marking the beginning of the studio’s regular appearance on the lists of the highest-grossing films. Since the release of hits such as E.T. (1982) and Back to the Future (1985), Universal has remained consistently present on those lists.

As is often the case in today’s world, rampant capitalism has led the studio’s future to be defined by agreements between financial giants in the media industry, which are of little interest to the film-loving reader. However, the nearly eighty years of the studio’s history presented in this article show that even giants, which today appear as unbreakable monoliths, have a turbulent past full of ups and downs. After all, who would have thought that this great Universal, for several decades of its existence, could not surpass the level of a studio creating films for local cinema chains, mostly located outside the major cities?