David Lynch’s DUNE Explained: Strangely Beautiful Disaster

…, stormed into the very insular world of Hollywood filmmakers. Although the story of John Merrick did not win Lynch an Oscar, it gave him something far more valuable — recognition. Dune

Positive reviews from all over the world ensured that Lynch was no longer treated as an eccentric curiosity, known only for one of the most disturbing films circulating among cinemas hosting wild, late-night screenings. The Elephant Man proved that the strange, young man who had once dedicated several years to creating a hypnotic madman’s dream could make a film that appealed to a much broader audience. What’s more, he could do it in such a way that people would reach for tissues and shyly cover their tear-filled eyes. After the final scene of David Lynch’s second feature film, tears were streaming down the cheeks of people who claimed they rarely got emotional during a cinema screening. One of them was Raffaella De Laurentiis, the daughter of the famous Hollywood film producer, Dino De Laurentiis. The 26-year-old woman, after watching The Elephant Man, knocked on her influential father’s door and, with tears in her eyes, declared that she had found the director for the film that had haunted not only Dino De Laurentiis but also several other highly recognizable artists for years. Two months after the Oscar ceremony, during which Lynch walked the red carpet for the first time, the American was chosen as the director of Dune, a film that, in the early 1980s, had one of the largest production budgets in cinema history.

Before deciding to collaborate with Dino De Laurentiis and his daughter, Lynch tried to raise the funds needed to produce a film that had been conceived in his mind even before directing The Elephant Man. Ronnie Rocket, a crazy story about a small man who, after an electrical discharge, becomes part superhero and part international rock music star, was waiting to be made but kept scaring away successive producers. The vision of a neon-lit, nocturnal city, the surreal script, and the accumulation of many strange, not fully understandable events and symbols definitely did not align with the calculations of a group of Hollywood bankers.

The person closest to getting involved with Ronnie Rocket was someone who had been rooting for Lynch since his Eraserhead days. Francis Ford Coppola used to show Lynch’s debut film to actors gathered on the set of Apocalypse Now to put them in a paranoid mood, to make them understand how the psyche of a terrified person works. After the premiere of The Elephant Man, Coppola invited Lynch to his estate. He flipped through the Ronnie Rocket script several times and then asked Lynch to read it aloud in his presence. After long hours of conversations, the Godfather director expressed his desire to involve American Zoetrope, the studio he co-founded with George Lucas, in the project. Unfortunately, it quickly turned out that Coppola would not be able to help Lynch, as he had fallen into serious financial trouble himself. The shooting of his musical, One from the Heart, began consuming more and more money. Ultimately, the film cost $26 million, which did not translate at all to box office success. After its 1981 release, the musical earned only $636,000 in the United States. This failure prevented the studio from engaging in Lynch’s project, which, due to his imagination, would not have been among the cheapest either. Ronnie Rocket was shelved once again. However, during his visit to Coppola’s, Lynch met a guest of his — the popular singer and budding actor Sting, who would soon don the Harkonnen family suit and fight for control of the sandy Arrakis.

From the beginning, Lynch was apprehensive about large budgets and producers considered to be big shots in the industry. He was also not particularly interested in directing a film created from another writer’s imagination. That’s why he turned down a lucrative offer from George Lucas, who had offered him the job of directing Return of the Jedi. The lack of freedom to alter the script, characters, and look of the Star Wars universe led Lynch to pass on the project, which went to Richard Marquand instead. When Dino De Laurentiis called him, Lynch was visibly surprised and thought there would never be a meeting of minds between him and one of the most influential producers in Hollywood at the time. In interviews, Lynch often mentioned that he decided to visit Laurentiis’s office out of sheer curiosity.

What’s more, although Frank Herbert’s Dune was a literary phenomenon and the story of its film adaptation was already becoming one of the greatest modern cinematic legends, Lynch had no idea what the producer was talking about during their phone conversation. For a large part of the conversation, he was convinced that Laurentiis wanted him to direct a film called June, not Dune. However, before meeting face-to-face, the director caught up and decided that Frank Herbert’s vision was remarkably close to his own. A brief conversation with the producer went in a way Lynch never would have expected. He felt that Laurentiis loved movies and that Dune was his pet project. The genuine enthusiasm from the Hollywood mogul made Lynch excited about the project, and he ultimately agreed to collaborate. That’s how another American dream could begin. However, in the history of cinema, Dune will probably forever be associated not so much with a dream but with a creative nightmare.

The Curse of Dune

The enormous publishing success of Frank Herbert’s novel led to Hollywood’s quick interest in acquiring film rights. Dune debuted on bookshelves in 1965. In the late 1960s, Arthur P. Jacobs, the producer behind the 1968 Planet of the Apes, was preparing to make a film adaptation. Unfortunately, a heart attack prevented Jacobs from embarking on a journey to the sandy planet filled with valuable spice. After his death in 1973, Dune resurfaced in the film market. It was then that Alejandro Jodorowsky and Michel Seydoux appeared on the scene, beginning efforts to create a multi-hour version of Dune, which they initially planned to release as a single film, screened without any breaks or division into parts. A unique mix of talents and personalities gathered around the project. The creation of the cinematic world was to be overseen by Jean “Moebius” Giraud (a renowned French artist) and H. R. Giger (the painter who designed the Xenomorph for Alien). They were to be assisted by Salvador Dalí, who agreed to help create visuals depicting the Dune universe and even act in the film.

Other potential cast members included Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, and Mick Jagger. The music for the film was promised by Pink Floyd, who agreed to collaborate after meeting Jodorowsky in a restaurant. The Chilean criticized them, saying they were more interested in eating burgers than participating in a great artistic endeavor. The argument must have struck a chord with the Brits. Despite Dune making it past the conceptual phase, leaving behind a legacy of magnificent storyboards and visuals depicting the smallest details of the Arrakis universe, the costs exceeded what the market could bear at that time. Jodorowsky fought to the end, but ultimately failed to secure funding, which meant the film rights reverted to the market. That’s when a massive fan of Herbert’s novel, Dino De Laurentiis, stepped into the fray.

De Laurentiis acquired the rights to Dune in 1978. Out of respect for the author, he visited Herbert’s ranch right after purchasing them, offering to let Herbert prepare the screenplay. The creator of the literary universe was eager to work on the adaptation, given complete freedom by De Laurentiis. However, it quickly became apparent that Herbert’s attachment to his book was too personal. He couldn’t remove any subplot, resulting in a 175-page typescript that would be impossible to translate into a film likely to captivate a global audience. Yet Herbert didn’t take offense at being distanced from the project. De Laurentiis changed his strategy, deciding to find a director before hiring a screenwriter, hoping that a filmmaker would impose a clear vision of what they wanted to achieve during production. The choice fell on Ridley Scott, who had just celebrated triumphs after the excellent reception of Alien — a film that would likely have looked very different without H. R. Giger’s work on Jodorowsky’s unmade Dune. After hiring Scott, De Laurentiis tasked Rudolph Wurlitzer with writing the screenplay, a writer known for Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid and the somewhat forgotten Two-Lane Blacktop. However, Wurlitzer quickly made a mess, introducing an incestuous relationship between Paul Atreides and Lady Jessica. Herbert’s outrage was so great that despite swift editing actions, the screenplay was essentially discarded. When it turned out that Ridley Scott’s vision was spiraling out of financial control as quickly as Jodorowsky’s insane project, the undertaking was hanging by a thread. In 1980, Ridley’s older brother Frank died unexpectedly of skin cancer. In mourning, Scott stated that he didn’t have the strength to devote two or three years to Dune. His departure ultimately ended another attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s prose. Shortly afterward, Raffaella knocked on Dino De Laurentiis’s door, and David Lynch joined the ship headed towards Arrakis.

Among the Sands of Arrakis

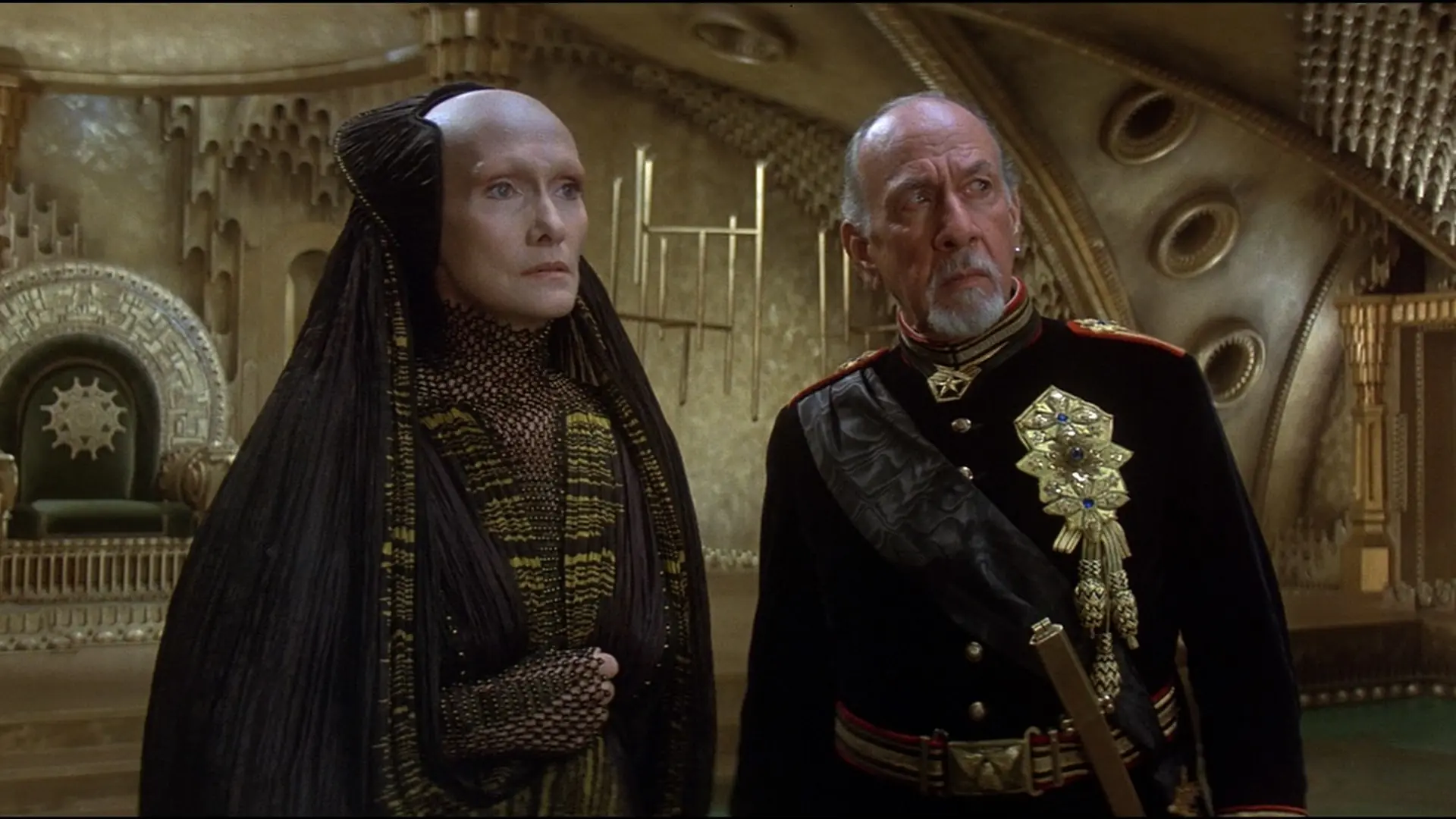

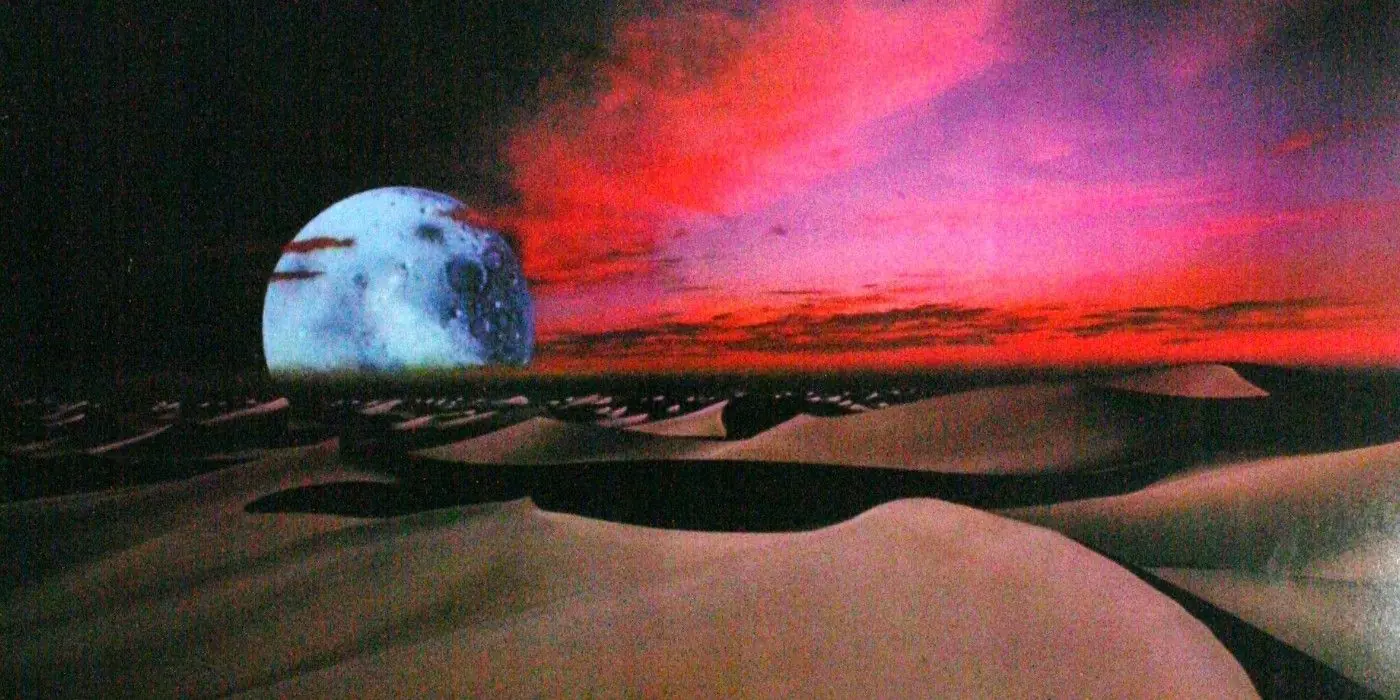

Immediately after signing the contract with the producer, Lynch set off for Tacoma, the home of Frank Herbert. The two men spent several weeks together, during which they got to know and like each other. Years later, Lynch would recall that the only issue they couldn’t agree on was the choice of a diner or restaurant for dinner. But that was a trivial detail. In the early 1980s, what mattered was that Herbert and Lynch communicated well regarding the adaptation of Dune. The filmmaker’s ideas pleased the author, who treated his most important novel like a child. This is not surprising since Dune is full of elements that resonate with Lynch’s fascinations. All kinds of dreamlike and hypnotic visions, rich descriptions of worlds with unusual textures, legends of the eternal battle between good and evil, the clash of the urban nightmare represented by the Harkonnen planet with the surreal harshness of the desert Arrakis — all of this certainly spoke to the American director’s imagination.

While Lynch was in Tacoma, the script for the film was being worked on by his friends, Christian De Vore and Eric Bergren (co-authors of The Elephant Man). However, their cinematic vision of Dune turned out to be so different from what Lynch had imagined that he decided to remove them from the project. With the scriptwriting position vacant again, the American knocked on De Laurentiis’s door and offered to take on the challenge himself. Initially, the producer wasn’t thrilled with the idea, but after receiving the first dozen pages of the script, he declared it the best Dune script he had read so far. Lynch was given the green light.

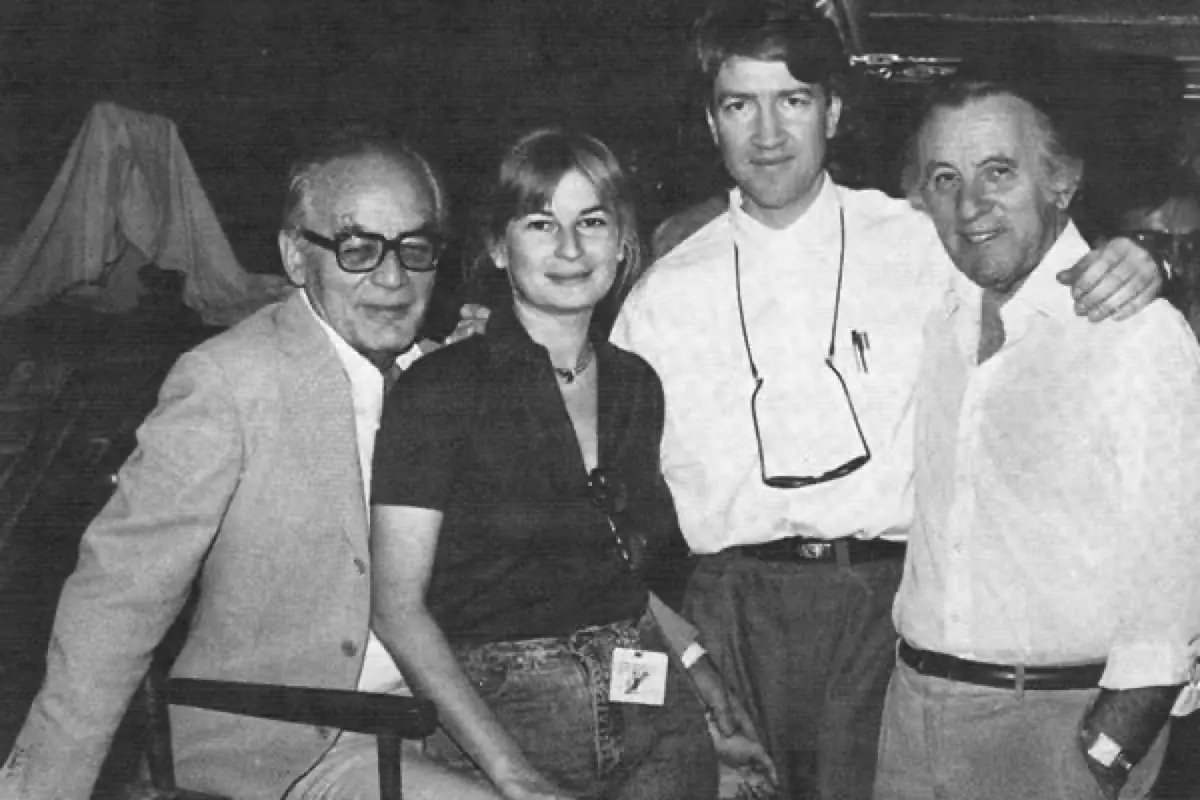

Around the same time, the team was being assembled, and locations were being scouted that could imitate the world created by Frank Herbert. Raffaella De Laurentiis, despite her young age, was appointed by her father as the coordinator of the entire undertaking. The choice eventually fell on the Churubusco studio in Mexico, located near the sand fields of Samalayuca, which once served as the backdrop for the gunslinger’s journey in Jodorowsky’s famous El Topo. It could be said that the spirit of the Chilean continually haunted the world populated by Atreides, Harkonnens, and Fremen. Churubusco was nothing like Hollywood studio complexes. The Mexican production halls were large, but the services provided by their owners left much to be desired. Frequent problems with power supply and malfunctions often disrupted work on the premises. Communication was also poor, making it difficult for actors and crew members to contact their families and agents. To make matters worse, the harsh climate, exacerbated by the studio’s altitude (over 2,000 meters above sea level), took its toll. A significant portion of the crew suffered from unpleasant ailments that frequently paralyzed film production.

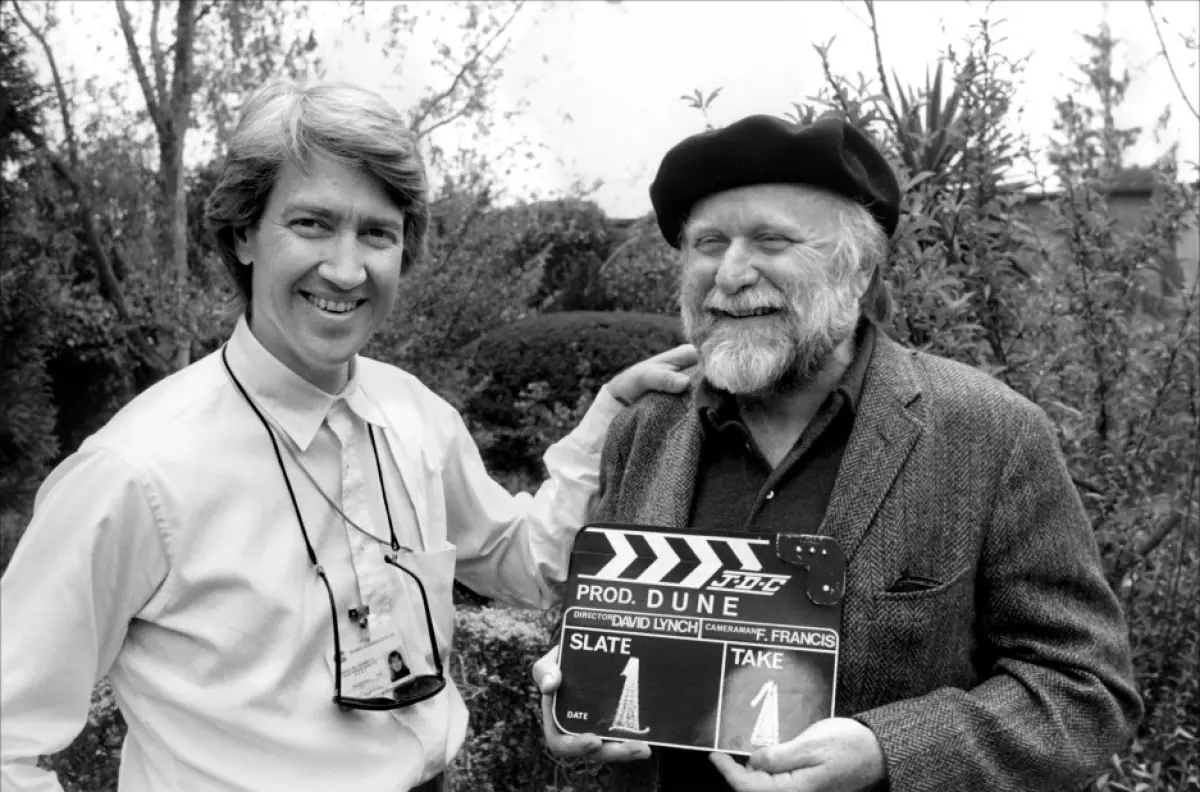

Lynch coped well with the difficulties of the set. From the early stages of the project, however, he was troubled by Raffaella’s insistence that the film’s length not exceed two hours. Given the complexity of Herbert’s vision, Lynch knew that containing the action within that time frame would be extremely challenging. To help manage the creative chaos, he relied on a carefully assembled team. Many of Lynch’s friends were involved in the Dune adaptation. The cinematographer was Freddie Francis, the director of photography for The Elephant Man. Sound effects were handled by Alan Splet, one of Lynch’s most loyal collaborators, who had assisted him during the creation of the short films The Grandmother and Eraserhead. Speaking of Eraserhead, Henry Spencer, aka Jack Nance, another close friend of the director, was also part of the film’s cast. Additionally, Tony Masters, the set designer for Lawrence of Arabia and 2001: A Space Odyssey, joined the project — interestingly, he had been rejected during the search for a set designer for Jodorowsky’s Dune. Carlo Rambaldi, responsible for designing and creating E.T. for Spielberg’s family hit, and Kit West, an Oscar winner for special effects in Raiders of the Lost Ark, were also on board. Even with actors like Sting, whom Lynch had met at Coppola’s villa, Max von Sydow, and Patrick Stewart (who would gain fame a few years later thanks to Star Trek), Lynch still lacked a lead actor to play Paul Atreides. Time was running out.