EX MACHINA. Brilliant yet slightly disappointing science fiction

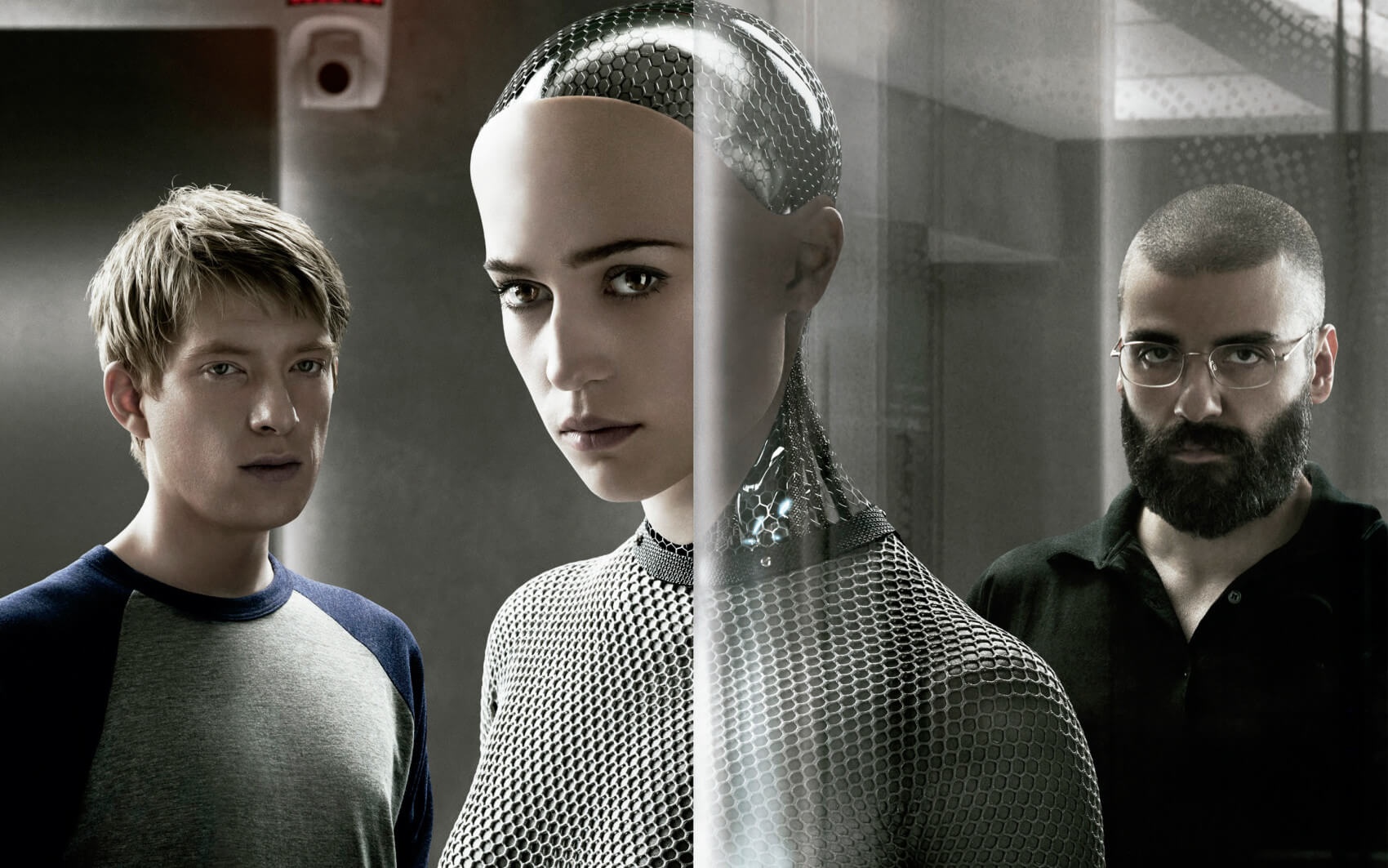

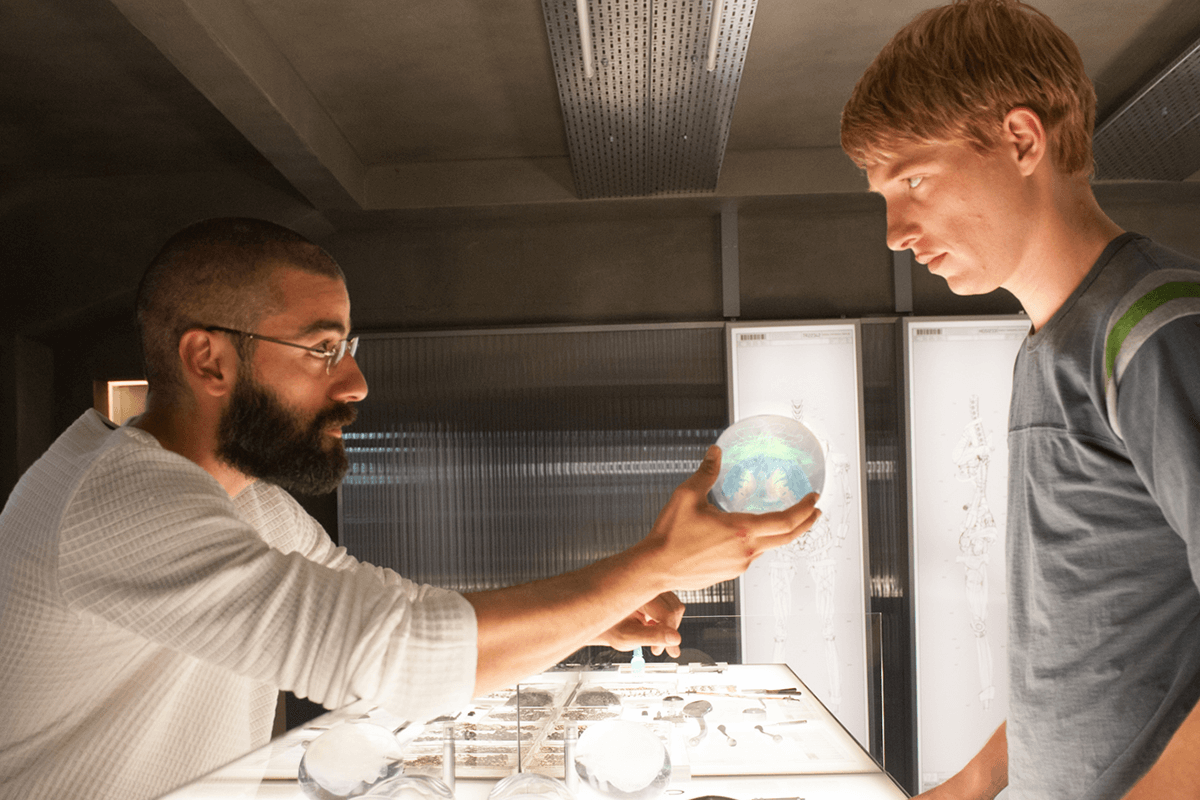

Caleb (played by the affable Domhnall Gleeson) wins a week-long stay at his boss Nathan’s (played by the rugged Oscar Isaac with a beard) impressive estate in a company lottery. However, it quickly becomes apparent that Nathan, a computer genius, has created Artificial Intelligence, and it is Caleb’s job to test it. The task is to determine whether Ava (with an angelic face portrayed by Alicia Vikander) is still just a machine or if she has become sentient. Ava’s body is comprised of wires, but she has a woman’s face and form, which complicates the task. Especially when, during frequent power outages, when all the cameras are turned off, she attempts to get closer to Caleb, sometimes using her own sexuality, arousing suspicion in her host.

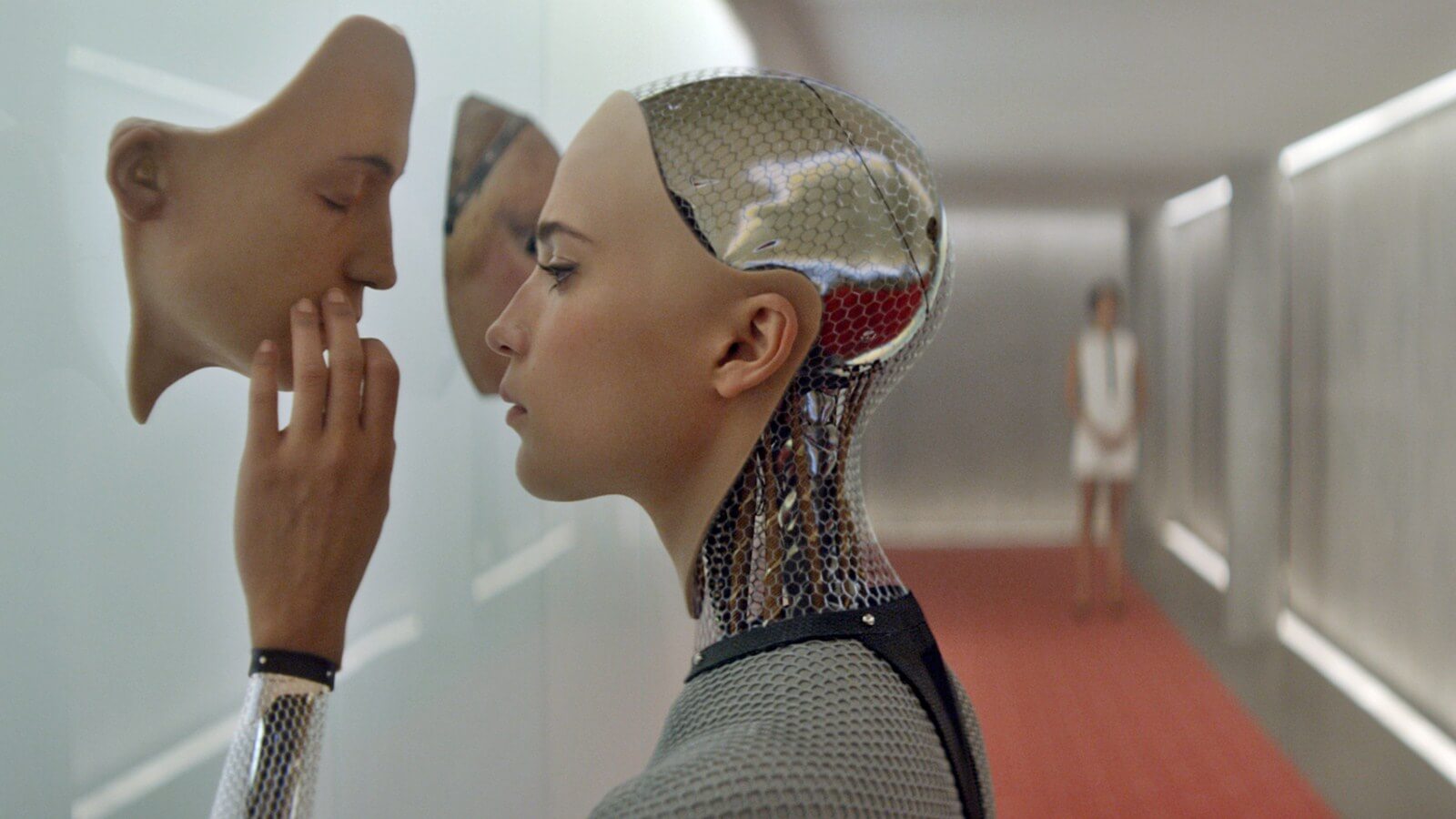

In Ex Machina conversations between the man and the machine take place behind a thick glass, somewhat reminiscent of the dialogues between Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter. His qui pro quo had its price, and so it is here – both are studying each other, seeking common ground that would not be based on their differences but rather their similarities. Or perhaps differences, but not stemming from the fact that one is a human and the other is not. Garland, much like the main character, eventually stops perceiving Ava as a mere marvel of technology and begins to be interested in her as a woman. The film raises questions about the need to assign feminine qualities to her, her sexuality, which comes to the forefront. Not only because it gives Caleb a reason to stop thinking of Ava as a machine, but also to leave the viewer with the impression that the story they are watching has a deeper layer. Just momentarily forget about the fantastic setting.

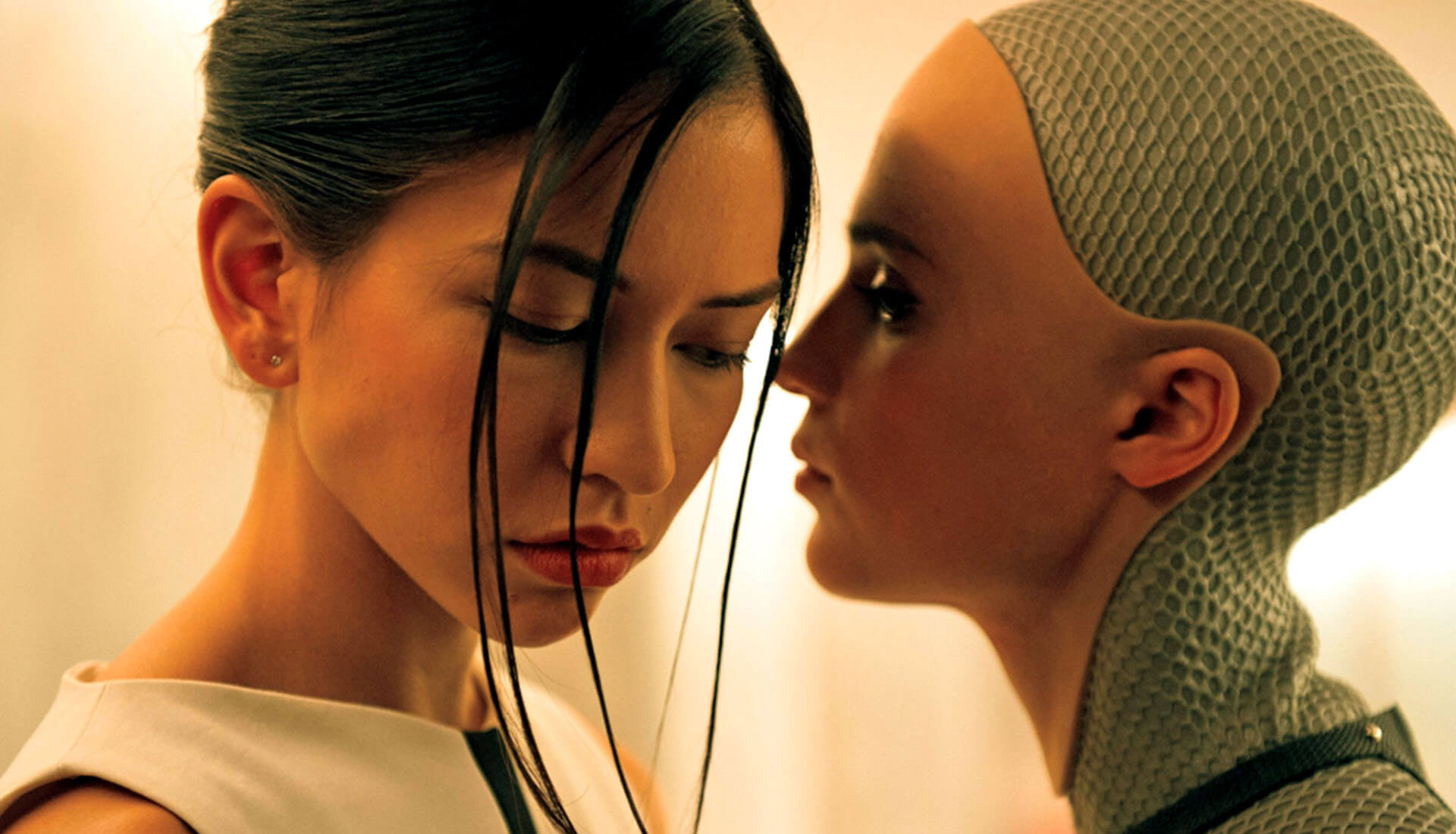

In addition to the three characters mentioned, someone else appears. Kyoko (brilliantly portrayed by the artificially human Sonoya Mizuno) serves as Nathan’s maid and serves him in various ways. She not only prepares meals and pours wine but also fulfills other desires of her master. Furthermore, she does not speak and seems not to understand what is said to her. Regardless of whether she is human or a machine – and it should be noted that she looks like a hundred percent human being – she appears as an object of arbitrary use. She is a body and nothing more. She is not locked in a glass room, nor is she subjected to research. But does that mean she is in a better position than Ava? She might seem more like an ornament than a full-fledged character in the eyes of the viewer. In reality, an impenetrable enigma, perhaps even the most intriguing character in the entire story.

Ex Machina ‘s director Alex Garland has made a name for himself as the screenwriter of intriguing films like 28 Days Later and Sunshine, both of which transform into displays of bloody violence in their finales. While in the case of the former, it was not only acceptable but even desirable (as it is a zombie-like horror film), the latter title carried much greater ambitions. Even the film adaptation of his The Beach, also directed by Boyle, found its resolution in violence. I won’t reveal how Ex Machina ends, although I also consider it an example of unfulfilled cinema.

Ex Machina begins brilliantly – the scene of winning the lottery is done without words, and in the next moment, Caleb is on a helicopter that will take him to his boss’s estate. Hidden in the woods, it gives the impression of being cold and empty. The minimalism of the interiors is designed to serve the work Nathan has prepared for himself and his guest. The sessions with Ava bring many surprises, arousing caution not only about the true intentions of the inventor but also of the director and screenwriter. This is intentionally a small film – the number of characters is limited to four, the action hardly ever leaves Nathan’s house, and everything is contained within the span of one week. This naturally serves to focus on the film’s main theme: the confrontation with Artificial Intelligence, the assessment of its ability to think independently, and the attempt to find an element of humanity within it.

However, after some time, this idea begins to blur. We watch two men and two women paired together. The older ones teach the younger ones that there are no feelings or love, only roles imposed on them from above. As a result, both the characters and we, the viewers, begin to wonder if there are still humans among them. And since even they doubt their own humanity, is it possible to even attempt to investigate the boundary between beings of flesh and blood and entities created from a tangle of wires and gel? Garland seems to have doubts about this. But there is no certainty because the intellectual duel between one group and the other turns into a war of genders. On one pole, there are Caleb and Nathan, and on the other, Ava and Kyoko. And all it would take is to reverse the roles, give the machine male traits, and make the tester a woman, leaving the relationships between the other two characters unchanged. This would have added an interesting dynamic to the story, avoiding the pitfalls of such simple classification. But such speculations are marginal.

My disappointment comes from the fact that Ex Machina was a promise of ambitious and gritty science fiction but stopped halfway. Just like Caleb, I stopped seeing Ava as a machine at a certain point, while, unlike the well-intentioned programmer, I realized that she would never make that mistake. Nathan is also too certain of his convictions (and cunning) for me not to predict the later development of the plot. In this regard, I prefer last year’s The Machine, which deals with similar themes, in which the scientist maintains caution and doubt until the very end. When you are smarter than the protagonist, you know that both of you have lost.