THE ELEPHANT MAN Decoded. A Heartbreaking Lesson in Humanity

The stay in Henry Spencer’s industrial hell was too extreme for many viewers, even for a film session lasting just a few dozen minutes. Lynch spent hundreds of days and nights in that hell.

The first half of the 1970s was a continuous fight for survival for him. He battled to find the funds needed to complete his debut feature film, as well as the means to support his family, which was beginning to fall apart. Just like the objects and characters that filled the frames of his cinematic outcry, expressing deep fear about what tomorrow might bring. In 1974, Peggy Lentz left Lynch, taking their child, Jennifer, with her. At that time, three long years were still needed to finish Eraserhead, during which Lynch’s mental state continued to deteriorate. When the film finally hit theaters and established a solid position among those who loved to lose themselves in the cinematic world under the cover of darkness—among a crowd of originals avoiding mainstream cinema and police scrutiny—Lynch began to slowly find his way out of his struggles. A light finally appeared at the end of the tunnel, a light that Henry Spencer had so desperately longed to see. The Elephant Man.

Awakening from the Nightmare

In 1977, Lynch married for the second time, this time to Mary Fisk, the sister of Jack Fisk, a long-time friend of Lynch’s who played a significant role in completing his first feature. Like most of Lynch’s acquaintances, Mary also appeared among the gloomy sets of Eraserhead, leaving her clear mark on the film. Henry’s child’s mother was a long-haired blonde, just like Peggy. The alluring neighbor who starts to draw the protagonist’s attention away from his wife has hair as dark as coffee. Mary’s appearance was similar, and coincidences were unlikely here since Lynch’s first divorce wasn’t caused solely by his creative madness. Peggy quickly noticed that another woman had entered her husband’s life. However, the separation didn’t mean a sudden break in all contact. Lynch’s ex-wife also entered a new relationship with Tom Reavy, who soon became a second father to Jennifer. Lynch accepted this state of affairs, and the couple never hindered his contact with their daughter. Peggy’s home was always open to Lynch, sometimes resulting in unexpected situations. One day, after returning home from work, Tom found a grotesque sculpture made of tampons and ketchup in the house. After such an encounter, he knew he didn’t have to worry about Jennifer’s whereabouts—she was undoubtedly with her biological father.

Aside from sculpting and collecting stones, which would later end up in a yellow ceramic bowl placed in the director’s living room, Lynch developed a near-religious devotion to the Bob’s Big Boy restaurant, where he indulged in hamburgers accompanied by sweet milkshakes. Years later, these culinary rituals would find their echoes among the pine forests of the town of Twin Peaks. Nevertheless, Bob’s Big Boy is significant here for at least two other reasons. It was at this restaurant’s table that Lynch worked on the screenplay for Ronnie Rocket. Over a piece of beef and a milkshake, he also had a conversation with Stuart Cornfeld, who, at the end of 1978, offered him the opportunity to direct The Elephant Man.

It was a close call for Ronnie Rocket almost to become another Eraserhead. Determined to bring his idea to life, Lynch went from door to door, only to find that none of the producers he approached were willing to give him the financial blessing he needed. A detective story about a dwarf who controls electricity, making him half-hero, half-rock star, was simply too strange an idea for Hollywood executives. Add to that an arch-enemy ominously named the Donut Men and a plethora of motifs that would later find their place in the director’s future films (alternate dimensions, hypnotic trances, rooms and spaces that defy the concept of clock time), and it’s no wonder that the bankers from Tinseltown didn’t see a profitable opportunity in any of it. Faced with continuous rejections and a chronic lack of funds, Lynch once again began to fall into depression, while tentatively considering the possibility of making Ronnie Rocket in the same guerrilla style that he used for his first feature.

He was saved from a personal disaster by Stuart Cornfeld, who remembered that during one of their previous conversations, Lynch had mentioned that he might consider directing a script written by someone else. As a result, somewhere between a milkshake and a burger, the script by Christopher De Vore and Eric Bergren ended up on the table at Bob’s Big Boy. Years after the film’s release, Lynch recalled that during his meeting with Cornfeld, he knew nothing about the story of John Merrick. But hearing just the words “man” and “elephant” was enough for him to know that he wanted to make the film. After all, he thought, it was so wonderfully weird.

Jimmy Stewart from Mars

After a series of consultations between the writers, Cornfeld, Lynch, and Jonathan Sanger (another producer committed to joining the project), the filmic story of John Merrick began to take shape. Yet there was still one major issue—funding. The leading studios didn’t see enough potential in The Elephant Man. Cornfeld and Sanger found every door they knocked on closed. When the situation seemed hopeless, the theater came to the rescue. A stage adaptation of Merrick’s story, directed by Bernard Pomerance, won the prestigious Tony Award, often called the theatrical equivalent of the Oscar. The buzz surrounding the title immediately caught the attention of those in charge of film budgets. However, the proposal to collaborate came from the most unexpected source. It turned out that the comedic giant Mel Brooks wanted to establish a production company that would support independent projects unlikely to receive funding from Hollywood’s major studios. Although Brooksfilm was an ambitious idea that would ultimately never become a hub for American avant-garde, it was enough to arrange a meeting between Sanger, Cornfeld, and Brooks. The master of absurd comedy took a serious interest in the project. There was just one catch—Mel Brooks had never heard of David Lynch.

At Brooks’s request, a private screening of Eraserhead was arranged. Lynch watched with mild apprehension as Brooks entered the room where the film was to be shown. Before the screening ended, the doors burst open, and Mel Brooks stepped into the hallway, shouting that Lynch was crazy and that he had just got the job. For Brooks, Henry’s industrial nightmare was a tale worthy of standing alongside the works of Beckett or Ionesco. Brooks even dubbed Lynch “Jimmy Stewart from Mars.” In his most famous roles, the American actor portrayed characters who grappled with obsessions and nightmares emerging from utterly ordinary, mundane places that anyone could recognize from their own lives (Rear Window, Vertigo). According to Brooks, Lynch’s terrifying dreams extended far beyond the window frames of shabby apartment buildings.

Among the Mists of London

Lynch arrived in London in the autumn of 1979, accompanied by his daughter, Jennifer. It was his first visit to Europe since a fifteen-day stay in Vienna, where, under the guidance of Oskar Kokoschka, he was expected to grow into the next great expressionist. However, the Austrian capital proved too sterile, too clean, lacking the cracks and dark corners that could fuel his imagination in the same way as the decaying neighborhoods of Philadelphia had during the making of Eraserhead. Initially, Lynch had planned his European escapade to last three years, but two weeks were enough for him to realize that his place was elsewhere. This is why the necessity of leaving the U.S. and working in London stirred up so many anxieties in him. As it turned out, those fears were unfounded.

Lynch quickly grew fond of London’s industrial character. Amid the dense fogs and cobbled streets, one could still feel the atmosphere of times when figures like Hyde or Jack the Ripper silently slipped between the alleys. The city’s decaying facades, presenting themselves to Lynch in various shades of gray, stimulated his imagination, attuned to urban decay—a vision that would, in the future, shape some of his most compelling portrayals of the downfall of American suburbs. Soon after his arrival, the search for filming locations began. Lynch visited countless abandoned hospitals and ruined buildings, barely standing under their own weight. However, one building caught his attention because, unlike the others, it still retained traces of the battle between life and death that had once taken place there. Abandoned beds, still-functioning gas lamps, and distinct hospital wards—this was the place for John Merrick. Only one issue remained. From his first encounter with London, Lynch knew he wanted to make a black-and-white film. He feared, though, that Brooks wouldn’t agree to such a choice for commercial reasons. Convincing the master of parody didn’t take long in this case. Brooks accepted the director’s vision and sent Freddie Francis to the set to ensure the quality of the monochromatic images.

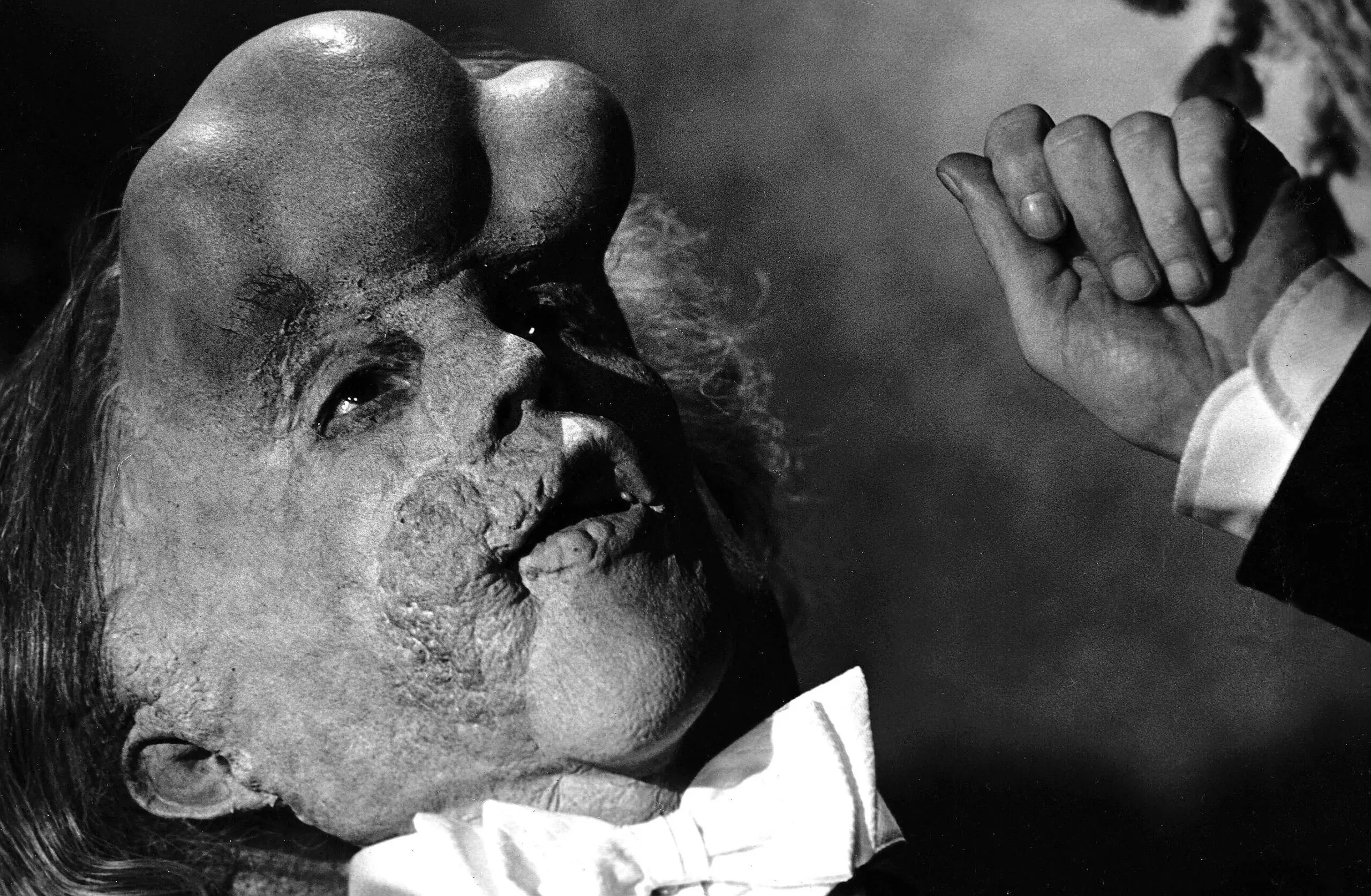

After assembling the cast, filming could finally begin. Ten days before the start of shooting, however, the team faced its first major challenge. They still didn’t know how the titular character would look. Merrick’s makeup was practically non-existent. Lynch, who until then had maintained total control over his projects, took this issue very personally, and he wanted to create the makeup himself. However, the skills he had gained while working on Eraserhead were not enough to design a mask or costume that an actual actor could wear on set. The grotesque child from Lynch’s first film had been a separate prop. Merrick’s costume, however, had to be tailored to the specific physiognomy of a real person, John Hurt. Tony Clegg, one of the production managers, recalls that Lynch’s design resembled a monstrous mask that could frighten kids at a birthday party. It was a total disaster. That’s why Lynch decided to hand the task over to a professional. Christopher Tucker took on the job of creating the makeup.

Lynch’s contribution to Hurt’s final look was, however, invaluable. Thanks to his friendship with a certain Mr. Nunn, the keeper of memorabilia related to Merrick, Lynch was able to persuade him to lend plaster casts of the real John Merrick’s arms and head for a short time, just as Tucker began his work. With these aids, Tucker was able to almost perfectly recreate the appearance of the historical figure. Proof of this success was Nunn’s tears when he first saw Hurt in full makeup. As for Hurt himself, he probably also shed some tears while transforming into Merrick, since he had to spend seven hours every day sitting in the makeup chair. During one of these long sessions, he reportedly came up with the idea to give his character the gentle, almost angelic voice we hear in the film. Hurt believed that anyone who endured such burdens daily must have been a messenger from the heavens.

Lynch was anxious about working on set, as it was the first time in his career he was dealing with actors who, unlike him, already had recognizable names. He was particularly intimidated by the thought of working with John Gielgud, though in the end, the most challenging dynamic turned out to be with Hopkins, who constantly questioned the young director’s competence. Their arguments ranged from trivial matters, like Hopkins criticizing Lynch’s eccentric wardrobe, to more significant disputes over the look of characters and, most crucially, the script and construction of scenes involving Dr. Treves. These clashes, however, were not destructive; they had a more creative character. Lynch allowed a good deal of Hopkins’s improvisation and listened patiently to his suggestions. One of their arguments even led to the decision to start filming before Hurt’s makeup was complete. Hopkins and Lynch agreed to try shooting the first encounter between Treves and Merrick without Merrick’s physical presence. The decision was spot-on, as Hopkins’s tearful reaction when he lifts the dark curtain and looks where the audience can’t see is one of the most powerful moments in Lynch’s filmography.

When the filming was completed, Gielgud sent Lynch a letter, asking with concern whether his performance was satisfactory. It turned out that Lynch’s minimalist directing style, his lack of firm instructions to the actors, and his openness to their improvisation led even someone as experienced as Gielgud to feel uncertain about his own work. For Lynch, who had initially been so nervous about working with established actors, this situation was quite remarkable. The renowned actor was now reaching out to the novice filmmaker, seeking validation for his otherwise excellent performance. Lynch, somewhat embarrassed, of course, responded with a letter full of praise. Both Gielgud’s role and The Elephant Man as a whole received acclaim from critics worldwide. The film earned eight Academy Award nominations but left the ceremony without a statuette. However, at that same event, Sissy Spacek, one of Lynch’s closest friends, won for her role in Coal Miner’s Daughter. In a way, then, it all stayed in the family.

The Burden of Being Seen

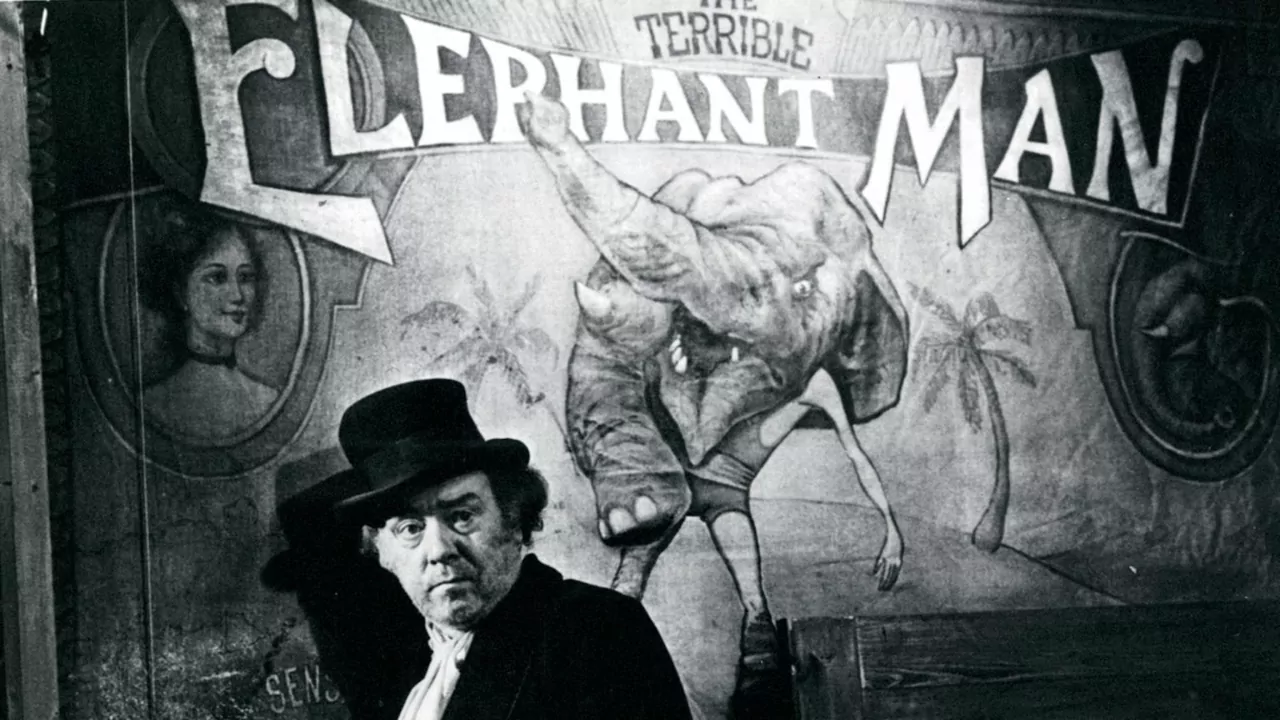

Dr. Treves meets Merrick thirteen minutes into the film. The tear running down his cheek during their first encounter significantly intensifies the viewer’s curiosity about the character, whose face will not be revealed for another eighteen minutes—over thirty minutes into the film. When a nurse, trembling with fear, opens the door and sees the horrifically deformed but utterly terrified figure lying on the bed, she screams and cries, recoiling in terror from the “monster.” She doesn’t notice what the audience does: Merrick fears human contact, he dreads being looked at, because throughout his life, no one has ever gazed upon him with tenderness or even the indifferent gaze we often exchange with strangers on the street. For Merrick, every glance he receives is a reminder that he is not seen as one of them. At best, he is a grotesque spectacle, a sideshow curiosity. To most, he is a wild beast, a creature that needs to be caged, positioned between the screeching monkeys and the fierce predators.

Lynch understands human psychology profoundly. The figure draped in cloth, appearing on movie posters and roaming the streets of London before revealing its true face, intrigues us. When Treves first approaches Merrick’s cage, we almost demand the camera show us the full view, to satisfy our desire to see. When the film denies this, our curiosity only grows stronger. Seeing Merrick becomes a goal in itself, overshadowing the moral questions that have surrounded his character since the film began. It’s in that very moment, when we finally do see Merrick, that Lynch confronts us with a figure as terrified as a child waking from a nightmare, crouched in a corner like a wild animal driven into a corner by man. We can’t help but feel like those Victorian gawkers, who would pay a few pence to glimpse the result of some obscene union between woman and beast. Until that moment, we haven’t seen Merrick as a human being, but as a twisted curiosity.

The burden of being seen accompanies Merrick to his death. Lying down, resting his head on the pillow, he finds peace, finally accepting his departure. But did his time in the hospital really change how people saw him? Did replacing the audience of working-class thrill-seekers with aristocrats make a significant difference? This is a question Lynch leaves open for us to ponder. Did these educated people recognize in Merrick the humanity that the residents of London’s industrial districts refused to see? Or was he merely another aristocratic toy, a means for them to reassure themselves of their goodness by offering him their sympathy? We are left to draw our own conclusions.

A Lesson in Humanity

The cinematic worlds of Lynch are filled with demons. They teem with violence, fear, and screams. This often diverts the viewer’s attention from what is most essential in these stories. For Lynch, throughout his entire career, what has remained most important is simply the human being—with all their flaws, desires, and fears. Perhaps this is why the tale of a Victorian outcast instantly became a story he wanted to tell through moving images. The Elephant Man is, after all, a true lesson in humanity, far from any kind of pathos, existing beyond the cold realm of philosophical ideas. Merrick’s childlike joy at encountering things as mundane as a photograph of children on a mantelpiece, the opportunity to speak with another person, or a visit to the theater, makes us realize how often we fail to appreciate those small things that, when combined, form our identity. They make us who we are.

During his stay in the hospital, Merrick begins to build a model of the cathedral visible through his window. It’s hard not to recall one of the most famous quotes of Saint Paul, who writes in his First Letter to the Corinthians: Do you not know that you are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you? For most of his life, Merrick could not look up to the sky. His deformity did not allow him to raise his head. Surely, he did not gaze toward cathedrals, which were sanctuaries for people, not for monsters. Before meeting Treves, Merrick was unsure whether he was even human. This is evident from the desperate tone in his voice when he shouted to the crowd surrounding him that he was not an animal, but a human being. A man who had spent his entire adult life earning a living as a circus attraction desperately sought confirmation of his humanity, which could only come from someone who could see beyond the mask of the Elephant Man. Yet nothing happens instantly; everything is a process.

For Merrick, this process concludes when the model of the cathedral is finished. It’s an obvious, perhaps even slightly clichéd symbol of his regained faith in his own humanity, but in Lynch’s hands, it takes on a truly extraordinary significance. It’s a beautiful and simple summation of all the small gestures that convinced Merrick that not every temple of God must be built according to the same principles or from the same material. As he leaves his model by the slightly open window, he has no fear that those who once treated him as a mere circus attraction will return. The transformation is complete. His dream of visiting the theater and watching a play alongside an audience has also come true. After all, animals are not allowed into theaters.

As Merrick lays his head on the pillow, he probably looks up at the sky for the first time in his adult life. And even if that sky is only the ceiling of a Victorian room, Lynch knows he must turn it into something more. After the character closes his eyes for the last time, the audience is presented with a view of hundreds of stars.

John Merrick dies because the Elephant Man had already died before he lay down on the bed.