THE MALTESE FALCON: The Legend of Crime Noir

…serves as a summary of both the essence of The Maltese Falcon, John Huston’s film and the titular dark object of desire for its characters. In both cases, we are dealing with some of the earliest (though not the first!) examples of film noir and the MacGuffin—a plot device often absent from the screen, insignificant in itself, but driving the story and its characters. No wonder, then, that the 1941 motion picture and its silent, black prop have become legends of cinema.

This film, also available in a digitally colorized version, was not Hollywood’s first attempt at adapting Dashiell Hammett’s detective novel. The Maltese Falcon was Hammett’s most popular and profitable work (though his The Thin Man and shorter stories like The Glass Key and Red Harvest, the latter inspiring the Coen Brothers’ Miller’s Crossing, were also adapted). Huston’s was the third Hollywood take within ten years—and the fourth overall, if you include Roger Corman’s later variation, Target: Harry.

A decade earlier, there was a fairly faithful adaptation with the exact same title (later retitled for TV as Dangerous Female). In this earlier version, the titular statuette seems a bit more predatory and ominous. The film itself, produced before the Hays Code, was bolder in portraying both violence and sexuality. However, lacking charismatic stars, Roy Del Ruth’s production failed at the box office and was relegated to obscurity due to the strict censorship that followed.

Five years later, William Dieterle made the weak Satan Met a Lady starring Bette Davis. Davis was the sole redeeming feature of this version, which altered key events to such a degree that the plot became nonsensical and dull. Critics were scathing, audiences unimpressed, and the film flopped. Perhaps it failed because both earlier adaptations opted for a typical, ill-fitting happy ending. Then, another five years later, John Huston entered the scene…

For his directorial debut, the legendary Huston also wrote the screenplay, earning him an Oscar nomination.

Huston’s The Maltese Falcon received two additional nominations—for Best Picture and for Sydney Greenstreet, a newcomer who dazzled in the supporting role of Kasper Gutman at the impressive age of 62. Critics joked that Greenstreet’s performance stood out primarily due to his size. Weighing over 160 kilograms, he barely fit into the frame, requiring custom-made wardrobes and furniture. His character later inspired Jabba the Hutt from Star Wars. Despite the jabs, Greenstreet delivered a flawless performance, as did the rest of the perfectly cast ensemble.

Gutman is a slimy, unscrupulous type—not just physically large but also cunning. Peter Lorre, for whom this was a favorite role, played Joel Cairo—a character as untrustworthy as Gutman, but “half the man” he is and much easier to manipulate. Cairo is a streetwise trickster whose lies are blatant. Wilmer Cook (Elisha Cook Jr.), the henchman, turns out to be more bark than bite; Iva Archer (Gladys George), the loyal secretary, provides the only genuinely friendly face. Meanwhile, Brigid O’Shaughnessy (played by Mary Astor, who reportedly had an affair with Huston during production) is a quintessential femme fatale, stirring the passions—and trouble—for the protagonist.

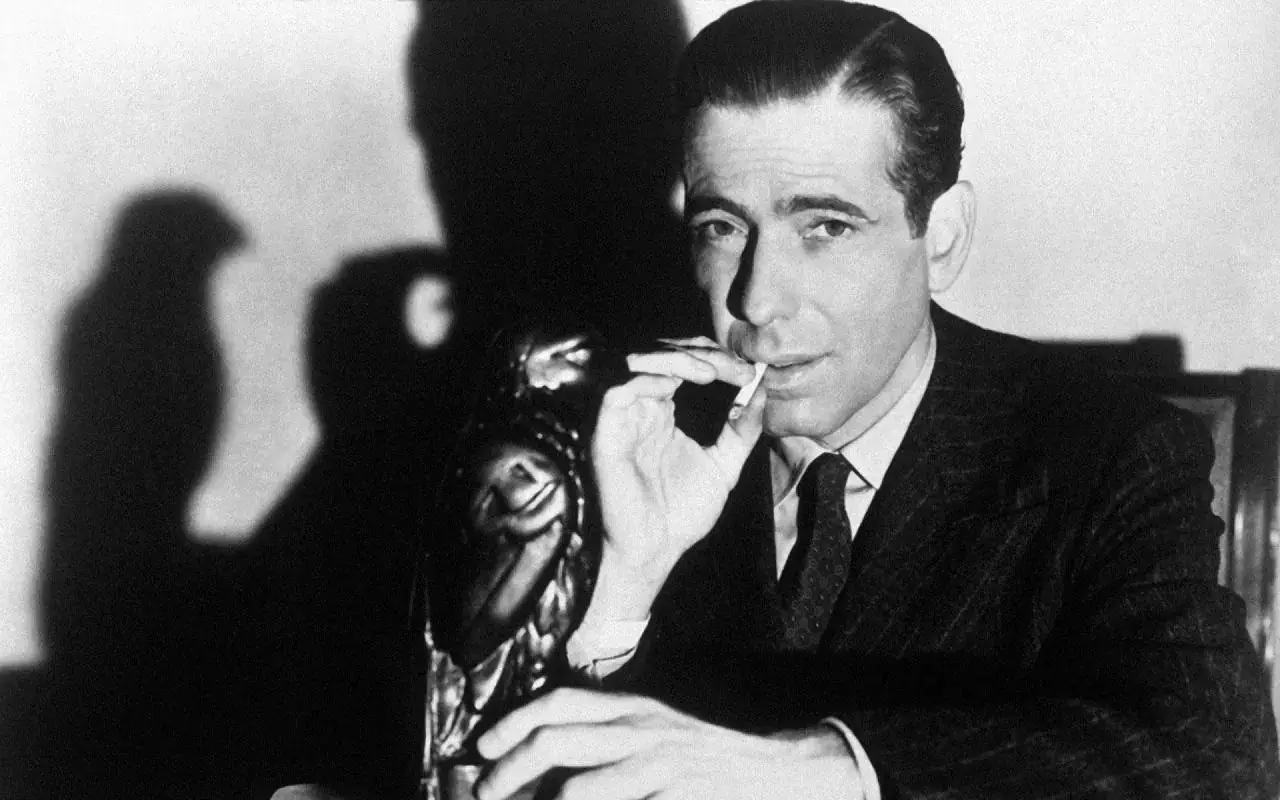

And then there’s him—Samuel Spade, iconically portrayed by Humphrey Bogart. For Bogart, this role, alongside The Treasure of the Sierra Madre seven years later, became his career-defining opus magnum. Ironically, considering that Bogie was the complete opposite of Hammett’s descriptions in the book, which Huston transferred to the screen with almost no changes. Just as in the book, we have Miss O’Shaughnessy, who one day appears at Spade’s office and, under a false name, hires him and his partner to find her sister—or rather, the man her sister allegedly ran away with. The woman pays them a substantial sum in cash, so the men accept the case. Soon, Sam’s partner, Miles (played by Jerome Cowan, who appears on screen for maybe two minutes), is shot dead before our eyes by an unknown assailant. Spade, suspected of the murder by the police, becomes the focus of interest for mysterious figures.

This is the core of a plot that, almost 85 years after its premiere, remains an undeniable classic—a benchmark not only of film noir but also of the detective genre. It still thrives on surprising viewers, uncovering new layers of mystery. And the more cards are dealt, the harder it is to resist the impression that all of them are marked. Like a ghost, the shadow of the titular bird hovers over them—a mythical object in Huston’s interpretation, whose fictional history, reaching back to the Middle Ages, already stirs the imagination during the opening credits. When the falcon is finally revealed, we—just as impatient as the players hunting it—may feel slightly disappointed, even cheated.

But this was intentional, as the story’s goal was to deceive both viewers and characters, who are willing to sell their souls to the devil to lay their hands on the statuette. Convinced of its uniqueness, blinded by its value, and driven not so much by dreams of wealth and glory as by sheer greed, they forget everything else, sacrificing the lives of others without hesitation and completely losing their heads over a statuette that is almost the polar opposite of the gleaming golden Oscar. But is that truly the case?

One must admit there is still something fascinating about it—enigmatic, alluring. Yet it is also disheartening, perhaps even terrifying. Shrouded in black, it gleams in the eyes of those entranced by it. Unwavering and silent, it serves as a perfect mirror for their shallow souls—a kind of guardian of human secrets and a marker of the unknowable. It personifies both desires and sins. Ultimately, it also bears witness to the downfall of humanity—its faith, naivety, and every weakness of the human condition. Ironically, the prop created by Fred Sexton turned out to be genuinely valuable over time.

Inspired by a real 17th-century jewel-encrusted figurine called the Kniphausen Hawk (now part of the Duke of Devonshire’s collection), it is today worth over one million US dollars. Or rather, they are worth that much, as four of the versions made for the film still exist. There is even a fifth, a golden replica created on commission for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the 69th Academy Awards ceremony. That version—adorned with platinum, rubies, coral, and a diamond—is worth as much as eight million dollars. In the book, the falcon was estimated to be worth about two million dollars. Meanwhile, the cost of creating all the original props—made primarily from polymer resin and lead, measuring nearly 30 centimeters (compared to over 40 centimeters for a real peregrine falcon), and weighing 2.5 and even 20 kilograms—amounted to only 700 dollars.

The film itself also became a box office success, earning back its modest $375,000 budget many times over. The financial and artistic triumph was so significant that Warner Bros., the studio behind the production, quickly decided to produce a sequel. Huston once again wrote the screenplay but did not direct Three Strangers, which was released in 1946 and ultimately bore little connection to The Maltese Falcon as originally planned. Although Lorre and Greenstreet reprised similar roles, legal disputes over copyright meant that entirely new characters appeared on screen. The resulting film was competent but could not hope to replicate the triumph—especially without Bogart as Spade on the payroll.

This makes the “first part” all the more exceptional. Today, the film—which was initially going to be titled something more cryptic, The Gent from Frisco—may not have the same impact as it once did. After all, the genre itself and the evolving careers of Huston and Bogart have produced several other equally great, perhaps even superior masterpieces. And the character of Sam Spade—the lone, silent, and tough crusader devoted to the cause—has been so thoroughly consumed by pop culture that today it is the epitome of a textbook hero, to the point of being almost cliché. An archetype teetering on the edge of parody. Nevertheless, the film’s resonance remains strong and relevant, and it itself remains an exceptionally sharp work. Put simply: among cinematic predators, this falcon still screeches the loudest. It’s worth listening closely.