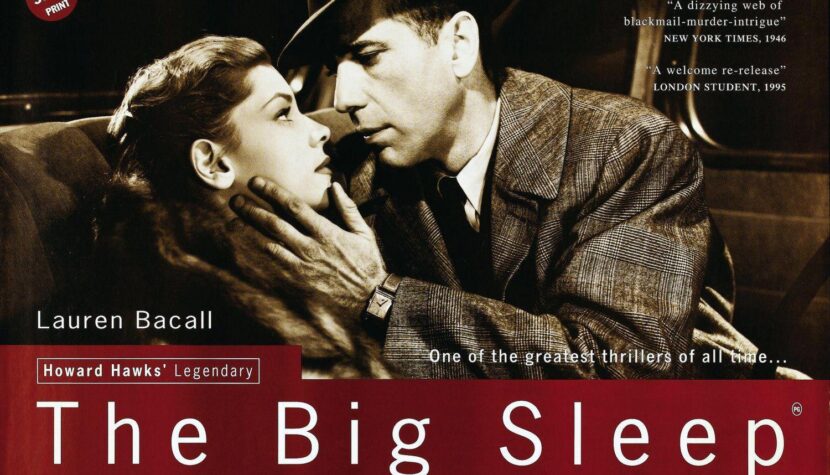

THE BIG SLEEP. Timeless crime noir classic

However, this was not the first film version of this story – the film was completed in January 1945 and shown to American soldiers stationed abroad. At that time, it had not yet received wide distribution, but the first critical voices were already reaching the creators, mainly concerning Lauren Bacall’s weak performance.

The actress’s agent, Charles K. Feldman, persuaded studio head Jack L. Warner to make some adjustments and re-edit The Big Sleep to strengthen Bacall’s character. Meanwhile, the actress suffered a severe setback with the film Confidential Agent (1945), and there were concerns that another wave of criticism could be very painful for her. The goal of the revised and supplemented II edition was to replicate the success of Hawks’ previous work To Have and Have Not (1944). The strength of that film lay in the relationship between the main characters, the witty dialogue, and the spicy remarks skillfully avoiding the requirements of the Hays Code.

Critics who saw both versions of The Big Sleep generally consider the 1946 edition to be a better film achievement, especially in terms of pacing, dialogue, and acting, but not in terms of plot clarity. Over the years, the film has been declared a timeless classic, but in the year of its release, many leading critics were not impressed. The re-editing involved the removal of several significant plot scenes, resulting in a loss of coherence in the story, making it more convoluted and confusing. However, this should not bother fans of Raymond Chandler, as the writer valued the atmosphere of the story built through sophisticated dialogue, strong character types, and evocative description of the world portrayed more than plot coherence. Howard Hawks’ film avoids didacticism; no one here tries to explain every detail unless necessary. There is also no explanatory dialogue about the title’s meaning, unlike the literary original (for comparison – another classic from that time, The Postman Always Rings Twice, contains quite unnecessary justification of the title).

The screenplay was worked on by the acclaimed writer William Faulkner, who years later was honored with the Nobel Prize (1949) and the Pulitzer Prize (1955). He collaborated with Hawks at least six times; the first time in 1933 on the war melodrama Today We Live, and the last time – twenty years later – on an (successful but underrated) attempt to create an epic historical drama, Land of the Pharaohs (1955). The adaptation of The Big Sleep marked the beginning of the director’s collaboration with the writer Leigh Brackett, who later became the screenwriter for Hawks’ westerns (Rio Bravo, El Dorado, Rio Lobo). In the 1940s, Brackett specialized in science fiction, but it was clearly not science fiction motifs that intrigued the Hollywood director, but her crime novel No Good from a Corpse (1944), written under the clear influence of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. To ensure a high-quality script, Hawks also hired other writers, primarily Jules Furthman, co-responsible for the success of To Have and Have Not (1944) based on Ernest Hemingway’s novel. Many sources suggest that the twin brothers Julius and Philip Epstein (Casablanca, 1942) also added some spice to the film with sexual undertones in a conversation about horse racing (“I bet on horses sometimes. I like to see the horses first, see if they’re worth betting on, get to know their strategy” or “– You have style, but I don’t know about stamina. / – That depends on who’s in the saddle”).

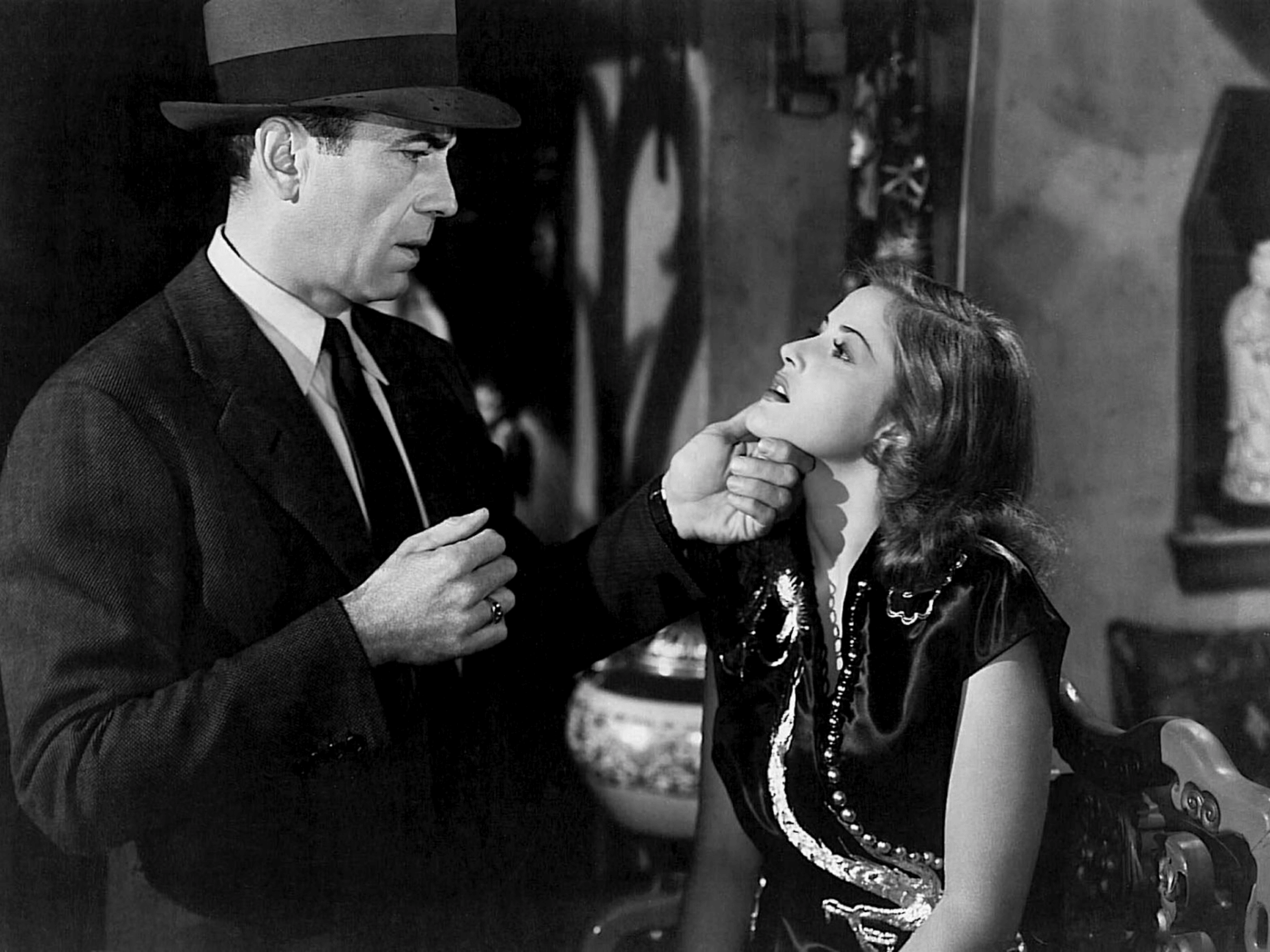

The film actually begins with a sex scene, or rather a suggestive allusion to a sexual relationship. During the opening credits, we see a man and a woman smoking cigarettes, and both butt ends end up in the same ashtray. This is how sex scenes were filmed when censorship boards armed with the Bible known as the Hays Code were concerned about the morality of the American audience. The idea of adapting Chandler’s novel was risky because it contains motifs related to pornography, and one of the characters is a nymphomaniac. For the director and screenwriters, it was a challenge to maintain this erotic atmosphere without showing nudity and sex, without using prohibited words, relying on subtle jibes, more or less readable to the viewer. For example, there is a scene where Lauren Bacall says, “You’re going too far,” to which Bogart replies, “Sharp words and aimed at a man who’s just leaving your bedroom.”

I haven’t mentioned yet what this film is actually about, and it’s probably worth outlining the plot, even if it’s widely known. The main character, private detective Philip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart), appears at the residence of General Sternwood (Charles Waldron). He was summoned and hired to help him and his daughter Carmen (Martha Vickers) escape the clutches of a blackmailer demanding repayment of gambling debts. The conversation takes place in a heated glass room full of orchids, which “resemble human skin – they smell of debauchery and corruption.” After the conversation, it gets even hotter when the sweaty Marlowe encounters the general’s daughter, Vivian Rutledge (Lauren Bacall), who exhibits unsettling behaviors as if she has something on her conscience. The detective’s first lead is an antique shop owned by blackmailer Arthur Geiger, where Marlowe tests the librarian’s knowledge of classics (asking about an edition of Ben-Hur from 1860). The multi-layered plot leads the protagonist to a casino owned by gangster Eddie Mars (John Ridgely).

There was something special between Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall that attracted viewers to the screen. Not surprisingly, they also formed a relationship in private life. Their chemistry was visible on screen, although it must be admitted that Bacall was not an outstanding actress, so without good writers, her role would not have been impressive even with the best partner. Therefore, their joint films were subordinated to this relationship, their verbal sparring, provocative gestures, and glances. As a result, they were not tightly plotted works, but they stood the test of time. In discussing this film, it is fair to praise the supporting and episodic roles as well. Carmen, played by Martha Vickers, was characterized as “like a child who enjoys tearing the wings off flies.” According to Raymond Chandler, she overshadowed Lauren Bacall in the original 1945 version, so her role was reduced in the reissue. But even in the trimmed version, the seductive Carmen is a striking, memorable character. Among the episodic performances, attention is drawn to 20-year-old Dorothy Malone, who ten years later won an Oscar for her role as a nymphomaniac in the melodrama Written on the Wind (1956, dir. Douglas Sirk). The scene from The Big Sleep where the actress takes off her glasses at Marlowe’s request is one of the ideas for an erotic allusion, but it can also be unfortunately interpreted as a suggestion that people wearing glasses cannot be beautiful.

Why is The Big Sleep considered a classic film noir? This genre is characterized primarily by a specific visual style rather than a fixed set of plot motifs. In the discussed production, the atmosphere of the created world matters more, consisting of characters who like the smell of cigarette smoke, streets bathed in rain and darkness, cars dredged from the lake, and stuffy rooms. The question of “who done it?” – often asked in Agatha Christie novels – is less important. What matters more is the investigative process of navigating through the urban jungle. This jungle is populated by shady characters – blackmailers, murderers, hustlers, and duplicitous women – but even the detective himself is not without flaws. He acts within the law, but sometimes the situation spirals out of control, overwhelming him. The investigative procedure requiring the use of gray matter can lead the protagonist to such a point that he is forced to confront violence. Something cracks in the human then – he becomes more calculating and cynical. Characters like Philip Marlowe and films like The Big Sleep are also referred to as hard-boiled. The historical background, such as World War II and the post-war period in the 1940s, is not insignificant – there was an atmosphere of mistrust in the world at that time, which was reflected on the movie screen.

The Big Sleep has lived for almost 80 years and has aged with dignity, still providing a lot of pleasure. The whole was created in studio conditions, adding a claustrophobic atmosphere to the film. I can’t say the same about John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941), which in my opinion is not as fascinating and atmospheric a work. Hawks’ direction is characterized by brilliance – his way of directing actors and delivering dialogue never makes the film too talkative. Certainly, the elegant style of camera work directed by Sidney Hickox, a regular collaborator of Raoul Walsh (e.g., White Heat, 1949), helps. There are many subtle camera movements that follow the characters’ movements. Perhaps the most dated aspect is Max Steiner’s music – classical orchestration for those times created according to a simple template… In short, we are dealing here with an excellent adaptation of a great novel – I recommend both Hawks’ achievement and Chandler’s. Thanks to cleverly constructed dialogues and well-chosen actors, the film provides entertainment even upon repeated viewings… The Big Sleep is death, but as long as we live, it’s worth revisiting classics because they offer a dose of emotions no less than the achievements of contemporary cinema.