M Explained: Fritz Lang’s Shockingly Relevant Masterpiece

The reasons for people’s attraction to this hypocritical ideology were, as always, the same—an escalating economic crisis, hunger creeping into the pots of an ever-growing number of citizens, declining living standards, and the ineptitude of the ruling parties. German intellectuals, artists, and politicians were aware of the gravity of the situation. The specter of Nazism began casting a shadow over a hopeful future. Nevertheless, most opponents of the Hitler camp did not attempt, even ideologically, to mount a broader fight. The more common phenomenon was a silent rebellion—an internal revolt against something that could not be stopped. M

Fritz Lang was one of Adolf Hitler’s quiet opponents. Lang’s opposition to the totalitarian state is clearly, albeit subtly, highlighted in his last two films made in pre-war Germany: M and The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. Chronologically, M was made in 1931, and the second part of the Mabuse saga premiered in 1933. It had to disappear from cinema screens shortly after its release due to its “incompatibility with the doctrine of National Socialism.” After this event, and after rejecting Goebbels’ offer (the Minister of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment saw a place for Lang in German cinema, ignoring the fact that Lang had Jewish roots), Lang left the Third Reich, leaving behind his wife and screenwriter Thea von Harbou, who had become obsessed with Nazi doctrine. This brief overview of the atmosphere surrounding the last two German films of Fritz Lang seemed necessary, in my opinion, to begin discussing his penultimate step and, in hindsight, perhaps the most decisive one (alongside Destiny) in the entire filmography of the German master—M.

M and German Expressionism in Cinema

Most film-related websites, not to mention the opinions of their users, claim with great pathos that M is the pinnacle of expressionist cinema—a kind of apogee of those fertile ten years of interwar German cinematography. I believe that such a carefree approach, devoid of any critical perspective on Lang’s film, is simply an infantile repetition of a slogan likely found on a poster or advertisement promoting a film that, in reality, needs no promotion. Even less understandable to me are attempts to compare it with films like Metropolis (Lang’s most popular film), The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (the cornerstone of expressionism created by Robert Wiene), or any other strictly expressionist film from the 1920s and 1930s. Unfortunately, we must call it by its name—this is sheer ignorance on the part of those writing about M.

Fritz Lang never adhered to the extreme formal expression initiated by the story of the somnambulist. Predatory building shapes, leafless trees distorted by a fantastical wind, and crazy worlds painted on canvases stretched between scaffolds in dark studios are elements we search for in vain in his German filmography. The closest film of Lang’s to Caligarism is probably Metropolis with its image of the city—a machine—and its people—soulless components in the background. This is not only because of the futuristic décor but also due to the extremely strong, almost naive contrast of white and black, where the former, of course, signifies goodness and mental clarity, and the latter, poverty, evil, and ignorance. Similar insinuations can be found in his Nibelungs, although the sharp color contrast there appears only in relation to one character—the cruel murderer Hagen. M is far from the formal extravagances of Caligarism, which—let’s make this clear—many mistakenly consider the only legitimate form of expressionism. On the contrary, M is formally stripped to a minimum, which does not mean it is devoid of formal virtuosity. This virtuosity manifests itself in individual scenes and shots, but it doesn’t jump off the screen like the fantastic, yet mad worlds of films à la Robert Wiene. In terms of aesthetics, M resembles Destiny, stripped of Méliès-like tricks, but there is once again a chasm between them in terms of content.

While Lang’s first film chronologically transports us to a semi-fantastic world—a reality in which Death can descend to Earth and test a truly loving woman—the story of a child murderer strikes with its realism. There is no place for fairies, golems, vampires, flying carpets, or Grim Reapers with big hearts. German folklore and the significant romanticism characteristic of expressionism fade away. Its remnants can only be glimpsed in the character of Hans Beckert, the titular murderer. He is, after all, a figure who hides a cruel secret behind an unassuming appearance—a man who is insane and torn by undefined forces that compel him to commit more murders. Despite his clear disgust for himself, he cannot stop the machinery of crime once set in motion. By harming others, he harms himself. A clear atomization of the hero’s mind is visible. The result is the emergence of two seemingly autonomous figures—the ruthless murderer and the clumsy victim of the wild desires of the former. This approach to man as a beast lulled to sleep by social norms is particularly close to expressionism.

It would be entirely unrealistic, in classical expressionism, to place criminals, police officers, and ordinary citizens on the same level. Just a few years earlier, Hans Beckert would probably have been depicted as a deathly pale madman with sunken eyes, wrapped in a jet-black coat that covered nearly every part of his body. In M, he looks like a clumsy citizen running out to buy fresh rolls for breakfast. Moreover, during the film, one of the criminals points out that the child murderer won’t look like a fairy-tale monster but, quite the opposite—“he could be a nice guy who plays marbles with the kids with a smile on his face.” The criminals and the police not only look very similar but also act based on similar logic—the logic of gain. The police are not keen on public opinion seeing their weakness (their inability to catch a serial killer). The criminals decide to take matters into their own hands because the increased police activity interferes with their work. Thus ends the era of clear value judgments emphasized by the contrast of black and white. The society in M is the result of these colors—everyone is gray and inclined toward both good and evil. This is far from expressionism, unless we stretch the whole argument to Hans’s character (the fragmentation of the mind, the inherent schizophrenia in the style of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde). In terms of content, M is far removed from most expressionist films that were successful enough to remain in the memory of some moviegoers.

The same goes for its form, which—like its content—is closer to Kammerspiel than German expressionism. Kammerspiel stood in opposition to the extreme unreality of films from the first half of the 1920s, focusing on depicting real life and real people. Thick smoke or fog, often playing a significant role in the story of the murderer, also brings it closer to the delicate imagery of Kammerspiel, distancing itself from the predatory contrasts of the “mad expressionists.”

On the other hand, drawing a clear, thick line between M and expressionism or M and Kammerspiel is not, and never will be, possible. This film draws inspiration from both of these different currents to create an innovative whole. That’s why I believe that M should not be naively seen as the apogee of expressionism. Lang surpassed any straightforward critical classifications with it. If it is the pinnacle of anything, it must be the pinnacle of itself—the pinnacle of M, as idiotic as that may sound.

Circumstances of Creation

Lang’s film appeared in German cinemas in May 1931. Just two months later, Peter Kürten, known as the “Vampire of Düsseldorf,” was sentenced to death for nine murders and seven attempted murders. It is certain that Kürten’s criminal spree took more victims. Until his execution, Kürten showed no remorse or regret for the fate of the families of the brutally murdered victims. Conversations conducted by forensic psychiatrist Karl Berg revealed that Kürten derived sexual pleasure from his brutal murders. He was particularly aroused by the sight of his victims’ blood (including that of young children). During his attacks, he also committed rape several times. Like many serial killers, he toyed with the authorities and public opinion by sending letters to popular newspapers. The police department announced a large monetary reward for his capture and even called for help from organized crime groups. Ultimately, Kürten was betrayed by his own wife, remarkably at his own request. One of his victims, a young woman, survived the attack and identified Kürten’s residence. Cornered, Kürten asked his wife to testify against him, motivated by the desire to ensure her a decent life after his death.

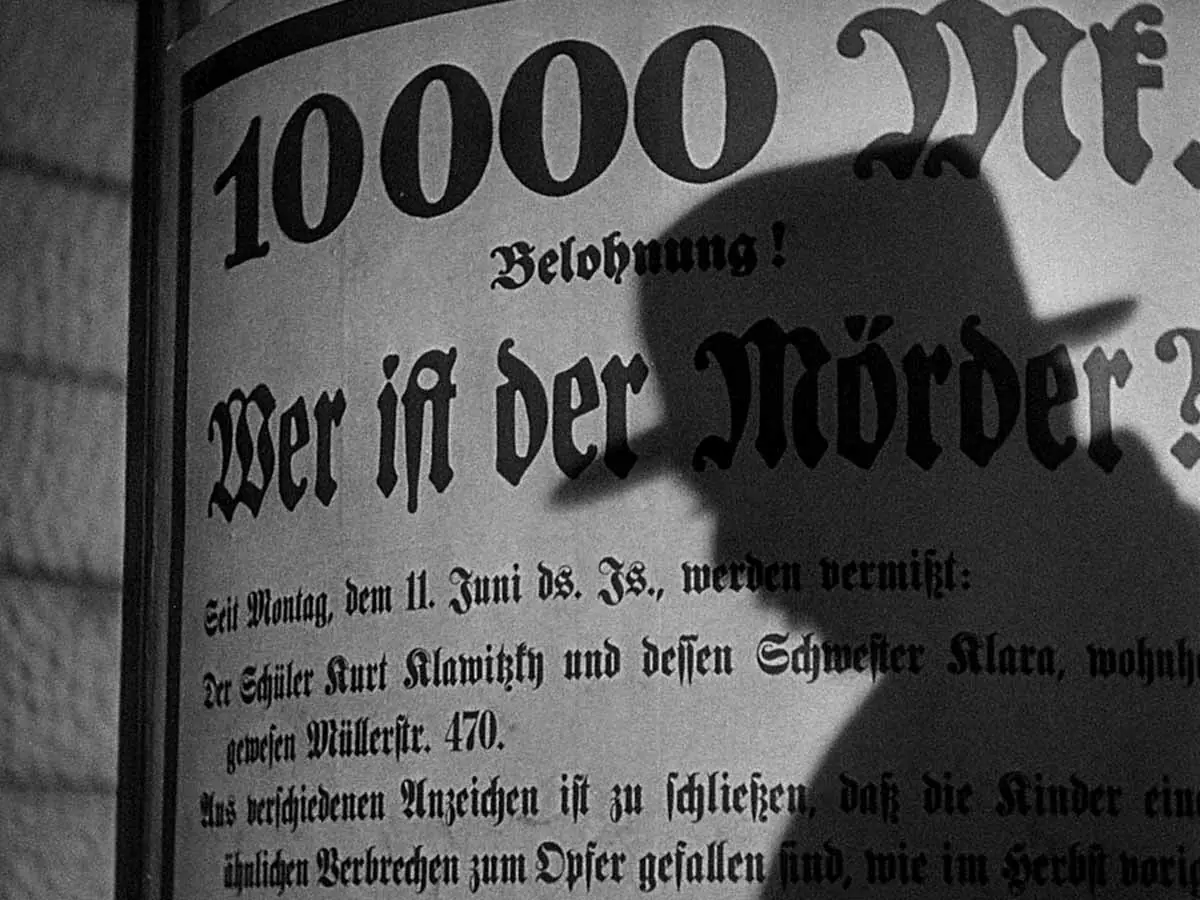

The analogies to M are obvious at first glance, yet—for reasons unknown—Lang opposed the idea throughout his life that Hans Beckert’s story was a film adaptation of the Vampire of Düsseldorf. Even the working title of M clearly hints at Kürten’s case. The murderer is among us (M – Mörder unter uns). The phrase was taken directly from a public announcement regarding the reward for capturing the serial killer, which Lang must have known about given the case’s widespread publicity.

Society, panicked by Kürten’s increasingly brutal crimes, began a full-fledged witch hunt, albeit in a more democratic form. Instead of using paper to start bonfires, people used it to write anonymous tips to the police. The number of leads collected by the police reportedly exceeded ten thousand. The reaction to this can be seen in one police officer’s refusal to release certain facts to the press, stating that it would only lead to more baseless tips. In a society gripped by hysteria, it became easier to lynch random passersby (a scene in which an innocent old man is almost lynched in M closely reflects this reality). The public mood was so frenzied that many people believed the killer lived within them (nearly two hundred cases were recorded). There is also a parallel between Hans’s “fondness” for children, especially little girls, who become the victims of brutal murders in the film. The film’s murderer, like Kürten, writes a letter to the press using a thick red pencil. Records show that Kürten’s letters to the press were written with a thick blue pencil. The final similarity is the fate of the villain—poena capitalis, or capital punishment, suggested but not shown in Lang’s film.

A decisive fact proving Lang and Thea von Harbou’s awareness of Kürten’s case is the research they did before starting M. While it might be believable that an average person, distant from the epicenter of the crimes, not reading newspapers or caring about criminal matters, could have missed the series of murders—though even that is difficult to accept given that Lang was not locked in isolation—it would be an abuse of trust to accept Lang’s claim that he was not inspired by Kürten’s case, especially when he and his wife carefully gathered information about all sorts of deviants by reading reports and interviewing forensic psychiatrists. Thus, M is certainly inspired by events in Düsseldorf, though not only by those. In the 1920s, there were three other infamous child killers: Haarmann, Denke, and Großmann.

However, I emphasize the word “inspired” in the first sentence of this paragraph. Lang used the facts he learned to build a film that has a completely different central point than the newspaper reports or stories about bloody murders. It seems the events in M are merely a pretext for the final two scenes: the basement trial and the legal trial. A pretext for discussing the justification of the death penalty, or perhaps more precisely, the righteousness of claiming the right to decide who is human and who has symbolically died, becoming human trash—a soulless beast.