STAR WARS Decoded: The Pop-Culture Origins of the Sci-Fi Epic

It was supposed to be an enthralling story set in a vast world, into which the viewer would be unceremoniously thrown. Simply put: a crazy vision that couldn’t possibly succeed, let alone make a profit.

Almost no one believed in the success of the concept, especially at the start of its production. However, reality turned out to be quite different from these pessimistic forecasts: Star Wars became the biggest hit of 1977, and four decades and tens of billions in profits later, there’s no sign of interest in the brand declining. Ironically, the existence of this colossal pop culture phenomenon is owed to a group of people who refused to sell Lucas the rights to adapt the adventures of Flash Gordon.

From Flash Gordon to Luke Skywalker

From a young age, Lucas devoured comics depicting the adventures of Flash Gordon. He was also a big fan of the old TV series that brought this world to the screen. Of course, he was fully aware of how poorly produced that show was, so he wondered what could come of a proper adaptation that utilized the best aspects of that fictional universe. Unfortunately for the then-unknown Lucas, and fortunately for the rest of the world, the owners of the Flash Gordon brand weren’t ready to entrust the title to a promising but still unproven director. They had their eyes set on Federico Fellini (and later Sergio Leone), so they simply dismissed Lucas with a terrible offer that the young filmmaker couldn’t afford at the time. The subsequent turn of events can be described as an ironic twist of fate: Lucas decided to create his own science fiction universe, and a delayed adaptation of Flash Gordon (premiering three years after Star Wars) turned out to be a financial flop, with many critics accusing it of being derivative of Luke Skywalker’s story. This is especially amusing, considering how much influence Flash Gordon had on Lucas’s creation.

Star Wars borrowed from Flash Gordon the motif of infiltrating the fortress of an evil emperor by two heroes disguised in enemy uniforms, rescuing a brunette princess, a friendly alien character with a somewhat animalistic appearance and large stature, and the style of the introductory text setting up the story. The influence of Flash Gordon is also visible in later installments, which featured storylines involving a sky city and a protagonist fighting a monster in a closed underground arena. The adventurous escapades of Buck Rogers and Germany’s Perry Rhodan also left their mark on the Star Wars saga as a whole. Beyond specific plot elements and character types, Lucas sought to capture the adventurous spirit and optimistic tone of the works that inspired him. George wanted to create something that would be the opposite of his well-received but bleak (and not particularly profitable) THX 1138. He believed that audiences, bombarded with pessimism and moral ambiguity, deserved a film that would make them feel good. Star Wars was intended to be an antidote to Taxi Driver, Dirty Harry, and other titles that critically examined the state of society at the time.

Legends of Ancient Wars and Japanese Officials

In pursuit of this goal, Lucas analyzed children’s films and fairy tales, trying to understand how their structure affected their reception. He wanted to make his project something akin to modern mythology. Star Wars was to begin long before the first frame of the film and last for ages after the final shot. The intention was to create a living world filled with its own myths and legends, a world with unlimited potential for development. George aimed for a fairy-tale quality but not kitsch—he made it clear from the start that he didn’t intend to create something superficial but something the audience could believe in. Many of the problems the characters face are rooted in our reality, making them easier to relate to; on the other hand, the action takes place in an unspecified time and place, imbuing these stories with a fairy-tale atmosphere and giving them the nature of legends.

Luke’s journey and the characters he encounters fit into the classic “hero’s journey” structure, as described by Joseph Campbell, who noted that most cultural works have been based on similar foundations for thousands of years. A hero living in routine, an element that disrupts that routine and leads them on an adventure, a mentor figure who teaches the hero new skills or ways of thinking, and a second act ending with the hero’s downfall… For those interested in the topic, I recommend The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and for those unconvinced, I encourage you to consider the plot structures of the first parts of Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and The Matrix—they share much more than it might seem! Lucas was well aware of the importance of these archetypes in crafting timeless stories, so he spent countless days consuming tons of comics, books, TV shows, and films, in an endless search for the golden formula. The formula for properly utilizing many existing elements to create something no one had ever seen before.

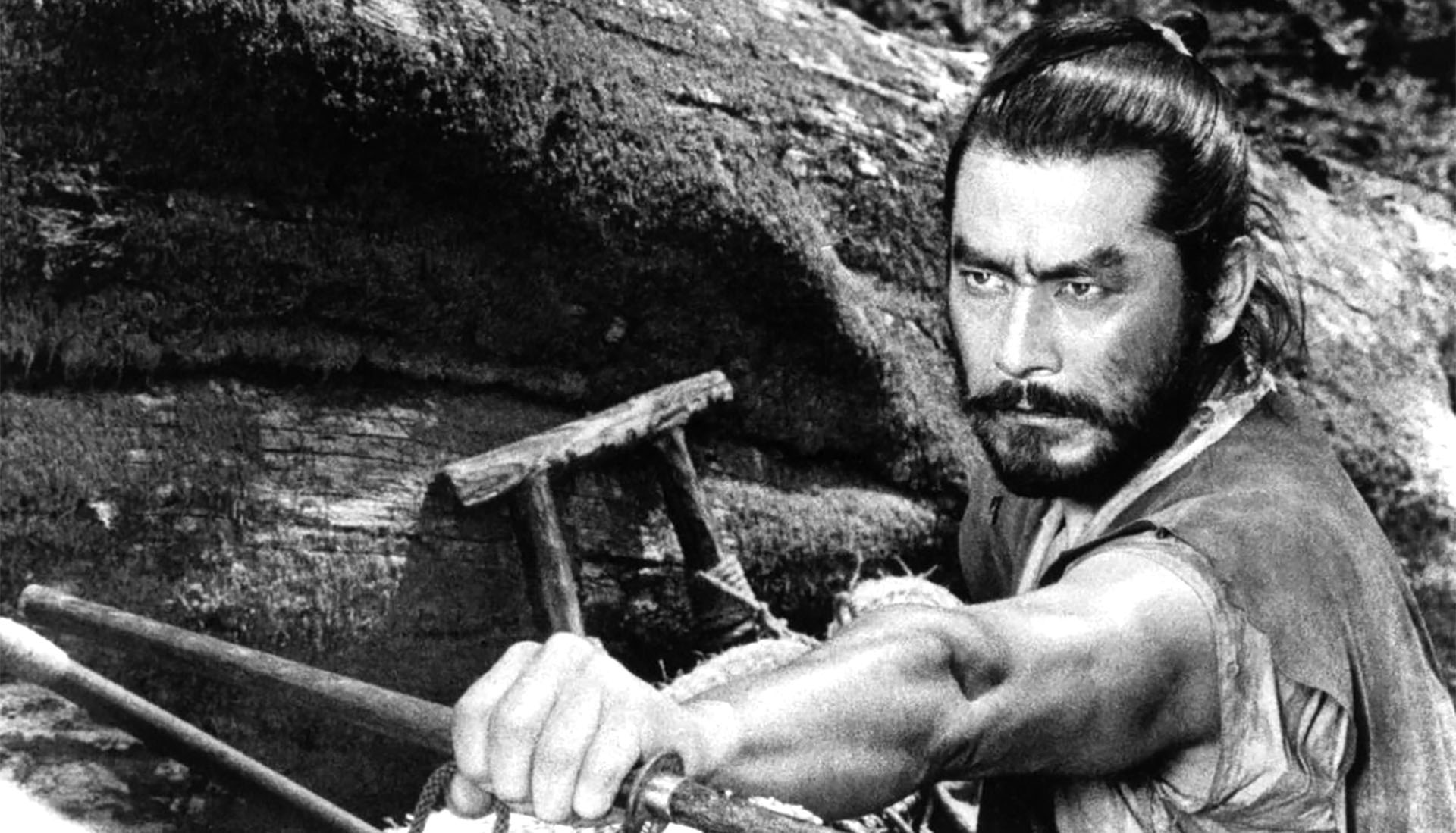

Thus, it was not just a simple remix of the adventures of a few heroic adventurers; in addition to the aforementioned pulp adventures, George was also fascinated by samurai cinema, especially The Hidden Fortress. Kurosawa’s work gave Lucas ideas for several plot twists and motifs (e.g., a princess asking for help from a battle-hardened general), which made their way into both the first story draft and the final version of the script, though their significance pales in comparison to the most important inspiration Lucas took from the film. The comedic duo of clumsy and constantly bickering officials immediately found their way into the gallery of Star Wars characters and eventually evolved into the two most recognizable robots in cinematic history – R2D2 and C-3PO. The decision to start the movie from their perspective (rather than the typical introduction of the protagonist), their argument, and the subsequent capture and enslavement of both robots—all of this was borrowed from The Hidden Fortress, which George also revisited while creating the plot of The Phantom Menace.

In addition to adventure stories and Japanese productions, Lucas always appreciated war cinema; one of his first ideas for Star Wars was an approach to depicting space dogfights inspired by this genre. He used scenes from films like The Bridges at Toko-Ri and Tora! Tora! Tora! as working material. Lucas edited cut scenes of airplane battles in the way he envisioned the confrontations between the ships that later became X-Wings and TIE Fighters. Incidentally, during the early stages of editing, clips from those films were used to structure the Death Star battle sequences, as the fighter battle shots were still being worked on. The director was particularly interested in achieving a sense of authenticity, mimicking the style of war documentaries; this was, in fact, how he originally wanted to approach Apocalypse Now, back when everything indicated that it would be his next project after American Graffiti. Lucas’s original concept may seem astonishing today: a story with elements of absurd black comedy, a small budget, black-and-white footage, real soldiers, a style bordering on documentary and newsreels, and filming in Vietnam during the war… However, due to various circumstances, this wild idea was shelved, and a disappointed George focused on Star Wars instead.

The persistent director, however, couldn’t entirely let go of Vietnam – in reality, the entire saga references the war and the events surrounding it. A poorly equipped group of freedom fighters going up against a superpower is one example of this idea. It’s worth noting that the superpower is unequivocally portrayed as the antagonistic force, which serves as a critique of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. This analogy becomes especially clear in Return of the Jedi, which depicts the primitive Ewok civilization aiding a handful of rebel soldiers in defeating an elite (!) legion of stormtroopers, despite the latter having a numerical and technological advantage. Despite these similarities, it would be mistaken to label the Empire as purely a jab at the United States. Upon examining the structure, rhetoric, and visual symbols of the regime, it’s easy to spot similarities to various totalitarian systems, especially Nazi Germany.

The Galactic Third Reich vs. Mystics with Laser Swords

Although the Galactic Empire bears some resemblance to the U.S. government in certain ways (Nixon’s presidency and the design of the Oval Office influenced the Emperor’s throne room in Return of the Jedi), Lucas always intended to evoke strong associations with Hitler’s regime in viewers. The Empire was also a dictatorship based on strict control of its citizens, who had relinquished democracy in favor of the “strong hand” of a figure wielding absolute power. The new order severely punished any independent thinking and discriminated against all non-human races – xenophobia, and even sexism, were deeply embedded in the functioning of a society where most women couldn’t even dream of serving in the army. Throughout his reign, Palpatine aimed to impose imperial dominance across the galaxy through totalitarian means. To achieve this, he resorted to propaganda, spreading fear and hatred within society, bloody wars, enslaving entire planets, mass genocide, and eliminating opposition.

Like Hitler, the Emperor had no qualms or moral reservations about committing unimaginable atrocities on an industrial scale. His will was almost always carried out to the letter by officers indoctrinated by imperial ideology, among whom murderous rivalry and sycophancy often masked blatant stupidity and incompetence (something Darth Vader had little patience for). These tendencies within the imperial army strongly evoke the reality of the Wehrmacht (especially its pop culture representation), while the uniforms of these officers were inspired by the actual appearance of Hitler’s soldiers (as well as 19th-century German Lancers). The similarities don’t stop there: the blaster rifle was based on the German MG-42, stormtrooper helmets resembled those worn by Nazi soldiers, and even the term “stormtroopers” itself is a direct reference to Sturmabteilung, the paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party – these are just a few examples.

Political suggestions and historical references didn’t end with the original trilogy; General Hux’s speech in The Force Awakens has such an obvious tone that even a swastika as a symbol of the First Order wouldn’t add much more to it. Palpatine’s rise to power also recalls not only the triumphs of Hitler but also the manipulations of Octavian Augustus, who similarly seized control of the Roman Senate before declaring himself emperor. The villains in Star Wars may seem exaggerated (especially the demonic Palpatine), but in reality, their characteristics are largely drawn from the darkest chapters of our history. This makes them all the more terrifying; they remind us of real people and real tragedies. Interestingly, their adversaries, the protagonists and supporting characters, are mostly derived from fairy tales and classic archetypes. While they possess enough humanity for viewers to relate to, their origins lie in cultural fiction. This aligns seamlessly with the escapist nature of Star Wars; while the forces of evil remind us of the reality we wish to escape, the heroes of good are as fantastical and abstract as possible without losing their necessary credibility.

Jedi Knights and the Force

The Jedi and the Force are perhaps the most fascinating elements of Lucas’s story; their evolution over the decades highlights the vast potential of exploring their nature. George describes the Force as a synthesis of all human beliefs he had the chance to study, though it’s undeniable that the greatest influence came from the Chinese philosophical concept of Qi. Like the Force, Qi permeates the entire Universe, and its manifestation is seen in natural phenomena and the existence of matter. These ideas significantly shaped the concept of the Force and the nature of the Jedi, who live in symbiosis with this cosmic phenomenon. Naturally, the figure of the Jedi Knight and the Order itself also draws from many sources – medieval chivalry, Japanese samurai, Greek philosophy, Buddhism, and Taoism are just a few examples. The prequel trilogy, and Luke’s teachings in The Last Jedi, carry an especially intriguing message about the Jedi – we see how an Order, with thousands of members, vast resources, and a council of the greatest masters, allows itself to be manipulated, makes terrible decisions, and partly contributes to its own downfall. In contrast, outcasts/novices like old Obi-Wan, Yoda, Luke, and Rey accomplish the impossible, freeing the galaxy from Palpatine’s oppressive empire despite being in utterly hopeless situations. A critique of structured faith while affirming the power of determined individuals who dare to leap into the unknown? It certainly seems that way.

It’s impossible to cover all the echoes of cultural history that resonate in Star Wars within this article. Numerous statements from Lucas and his collaborators point to dozens, if not hundreds, of references worthy of more or less attention. Who knows how many inspirations George never spoke about or wasn’t even aware of himself? Isaac Asimov’s Foundation, the works of E. E. Smith, Frank Herbert’s Dune – I’m mentioning these muses here for the first time in this text, and even within them, there’s a wealth of allusions and borrowings. Referring back to the question posed in the title of this article: I absolutely disagree with calling George Lucas a plagiarist. Borrowing an idea is one thing. Utilizing such a colossal number of elements from across art, pop culture, and history, and merging them into a coherent, original vision, is a true mark of a visionary. It’s like gathering a thousand diverse, often incompatible pieces and arranging them into a perfect structure. And if someone calls it a cultural remix? It’s hard to see that as a criticism in a world that’s been remixing existing content for as long as we can remember.