The Hays Code, or what HOLLYWOOD CENSORED for 30 years

In the history of American cinematography the years 1930-50 are considered the golden age of Hollywood. At that time, Dream Factory produced over 400 films a year, and 90 million viewers visited American cinemas every week. In the same time the Motion Pictures Production Code, more widely known as the Hays Code was in full effect. William Harrison Hays was an American politician who headed the Association of American Motion Picture Producers and Distributors. The Code of Production adopted by this association oversaw the content of each American film, trying to improve the tarnished image of Hollywood.

Hollywood on the verge of decency

The brutalization and frivolity of film language, numerous scandals involving movie stars, such as the murder of director and actor William Desmond Taylor or the alleged rape of actress Virginia Rappe by the famous comedian Fatty Arbuckle, shocked American society. Pre-Code films were characterized by unprecedented daring and unprudishness. Productions from 1920–34 were often full of promiscuity, prostitution, sex, miscegenation, homosexuality, drug addiction, violence and gangsterism. Hollywood actresses played the roles of strong, independent, seductive women, often portrayed in provocative, skimpy outfits – like the star Jean Harlow, who played a prostitute in the 1932 film Red Dust. Gangster life, such as in the 1931 movie The Public Enemy, was more often glorified than condemned thanks to the rising fame of American gangsters Al Capone and John Dillinger. Morally devastated Hollywood severely condemned political, religious and civic organizations. They called for the introduction of censorship, which was to restore law and order in the factory of dreams. Scenes full of violence and brutality, such as in the 1932 film Scarface, and bold and provocative scenes, such as the 1930 Morocco of Marlene Dietrich kissing another woman, were to disappear from the screen for good.

The Production Code at the service of cinema

New regulations were adopted in 1930, but they became legal four years later – then a new Production Code Agency was created. Film studios adopted the new regulations in hopes of avoiding top-down government censorship. For almost three decades, the Hays Code has been a guardian of the moral integrity of films produced and distributed in America. It contained many guidelines specifying what content is acceptable in American cinema, and what content should be avoided like the plague. He was guided by the most important principle – no image should question the viewer’s morality. The film should avoid topics referring to evil, crime and sin. Crimes and offenses could not be portrayed in a positive light. If any of the heroes committed an immoral act, the villain had to be punished. The family in the film was supposed to represent a conventional model. It was forbidden to show interracial and non-heterosexual relationships, and marital infidelity – if it had to occur – was presented as an unworthy act. The Hays Code also prohibited the display of nudity and references to sexual behavior. Kiss of film lovers could last no more than 3 seconds. The scenes of drug dealing also disappeared from the screens, and the lines abounding in profanity from the script. The words “Jesus Christ”, “damn” or “hell” were also not allowed to come out of the actors’ mouths. No film could mock faith and religion. Priests, clergy and nuns were presented with due exemplification and respect.

Every film, sooner or later, fell under the scissors of insensitive censorship. Frank Capra’s 1934 film It Happened One Night was one of the first productions to comply with censorship, thus ensuring a generous remuneration and the film’s lasting success (it won as many as 5 Oscars). In Capra’s comedy, unmarried characters Peter and Ellie, played by Clark Gable and Claudette Colbert, spend a lot of time together – even sleeping together in the same room. Frank Capra found a way to protect the bed scene from excessive obscenity. When the heroes get stuck in one motel room, Peter hangs a thick blanket between the two beds, ceremonially calling it the Walls of Jericho. Claudette Colbert does not reveal an inch of skin – she presents herself in pajamas buttoned up to the neck. And when Peter wants to give the woman a lesson in undressing, she runs away in terror. The director, however, managed to preserve the romanticism of the scene in a subtle and innocent way. Despite the lack of intoxicating passion and strong desire, one can clearly feel the love tension between the two protagonists.

Jane Russell’s exposed, round breasts became not only the most important decoration, but also the showcase of Howard Hughes’ 1943 western The Outlaw. The director designed a special bra for his star to enhance the actress’s breasts. And it was because of them that the film ended up in a drawer for two years before it appeared on the silver screen for good. Hughes began an unequal battle with the censors, who demanded that Russell’s most racy scenes be cut. The controversy surrounding the film’s release turned into the great publicity the director needed most. The action aroused enough interest for a slightly modified film to be released in theaters for one week. Finally, The Outlaw was released three years later, in 1946, and the premiere was accompanied by a huge box office success.

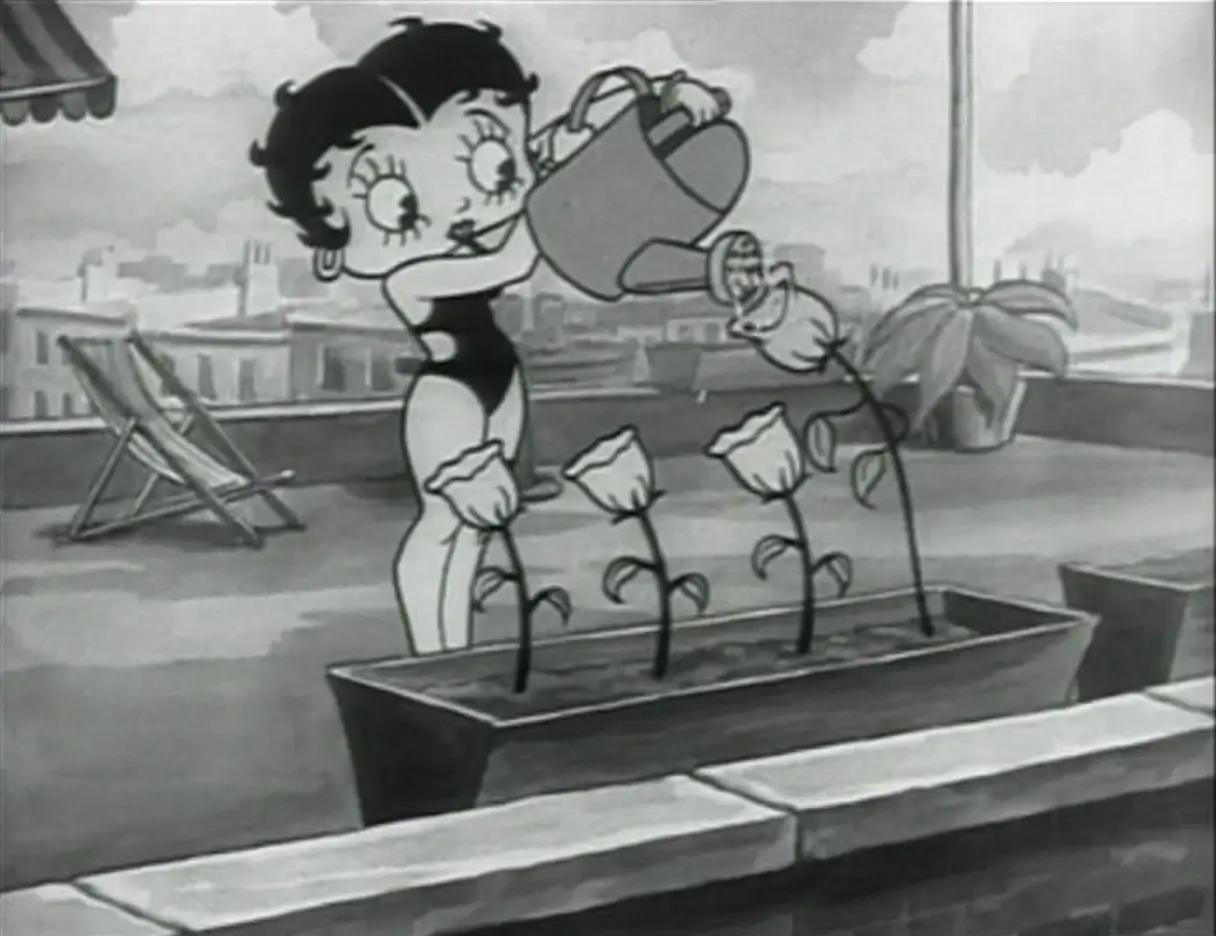

Even the most popular coquette in the United States – Betty Boop – did not escape the censorship. The cartoon heroine with extremely feminine shapes entertained with her frivolity and carefreeness. After the introduction of the Code, Betty lost all her attributes: she exchanged tempting short skirts for long dresses, covered her legs with stockings, and covered her neckline with chaste collars. Betty’s metamorphosis became the most drastic example of the stiffness and sanctimoniousness of censorship.

The use of profanity of any kind was strictly prohibited by the Code. However, Clark Gable’s most famous line from Gone with the Wind in 1939 reads: “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn”. The producers of the film had a long dispute with the censors, with difficulty persuading them not to cut out the offensive word. The issue was eventually saved from modification, but David O. Selznick, the producer of the film, had to pay a five thousand dollar penalty. It paid off, to this day Gable’s statement is one of the most characteristic in the history of cinema.

Criticism and abolition of censorship

It’s no secret that the Code was like a splinter under the fingernails for producers and directors. With its lofty, prudish assumptions, it was at odds with the interests of the film industry and the expectations of a thrill-hungry audience. Thus, it was not uncommon for filmmakers to try to circumvent the bans imposed on them in all possible ways. The famous scene from Notorious from 1946 became a flagship example of open opposition to Hays’ directives. Alfred Hitchcock stand up for the independence of the American kiss. The code stipulated that a close-up of lips in a film could not last longer than three statutory seconds. The director found a way around the guidelines. In the famous scene with Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant, the director interrupted the intimate close-up of the actors every few seconds. Finally, the kiss scene, composed of several autonomous, passionate kisses, lasted two and a half minutes.

Hitchcock became an artist whom the censors did not let out of their sight. With each new project of the director, they had their hands full. It is no surprise that the most famous film scene of the master of suspense – the shower scene from Psycho, 1960 – aroused the most controversy. Not only was the brutality of the murder scene offensive, but so was the nudity of actress Janet Leigh. Hitchcock’s camera operated with many close-ups, however, a thorough study of the heroine’s body was abandoned. To completely remove the suspicions of censorship, Leigh’s breasts were covered with pink moleskin – a dense, thick fabric imitating human skin. The 1960s, however, were the period of the Code’s last jolts. The censors were losing their reputation – they were becoming more and more lenient, so after lengthy negotiations, Hitchcock was allowed a few innocent walks in Janet Leigh’s underwear.

The Hays Code was losing its strength. Year after year, the censorship became less and less rigorous, allowing bolder productions to be distributed. Filmmakers slipped censorship more and more often, until finally disregarding the Code’s directives became an open secret. Moreover, the words of criticism became clearer. The code was accused of prudishly showing human sexuality, trivializing the image of a woman (completely subordinated to a man) or racial discrimination. The film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner from 1967 turned out to be a breakthrough in this regard. The winner of two Oscars, in a humorous and intelligent way, talked about the relationship of a young white-skinned woman with an African American, whom the girl’s parents oppose.

The end of censorship came in the 1960s. The Hays Code died a natural death in 1968, and LGBT activists, feminists, the young generation of the hippie movement, questioning the conservative, parochial activities of their parents, contributed to this, which was also reflected in the cinema. The time has come for a sexual revolution, liberated films, such as Blowup from 1966 or the Swedish I Am Curious (Yellow) from 1967, which was banned in the US for depicting sex too boldly, but more on that in another article.

Today, in the times of bold and shocking cinema, it would be impossible to accept similar restrictions from 80 years ago. All the films we know today would undergo a brutal modification. In each of them there is a dose of eroticism, violence and innocent indecency that we like. Nevertheless, the films of Hollywood’s golden age boast such a title for a reason. Despite the prevailing censorship, the best works in the history of cinema were created at that time. The Hays Code has proven that good cinema is not only based on controversy, frivolity and iconoclasm. Restraint didn’t have to be a limitation at all, and many artists of that period used it to create elegant and sophisticated cinema.