Everything there is to know about GERMAN EXPRESSIONIST CINEMA

As the 19th century was coming to an end, as doubts slowly crept in about the old man who had so generously endowed our civilization, whether, in his final days, he could bestow upon us anything more, a group of women marched out of the Lyon factory with smiles on their faces. There would be nothing unusual about this if this particular procession had passed through the square in front of the factory gates. However, their journey took place in a completely different location and, lo and behold, without their direct participation. The female workers were, in fact, marching between the frames of a celluloid strip, which, thanks to a certain magical box created by the manufacturers of photographic materials, the Lumière brothers, came to life and started moving amidst the solid walls of the Indian Salon. The 19th century amazed us once again, assisting in the birth of another muse: in 1895, it gifted us with cinematography.

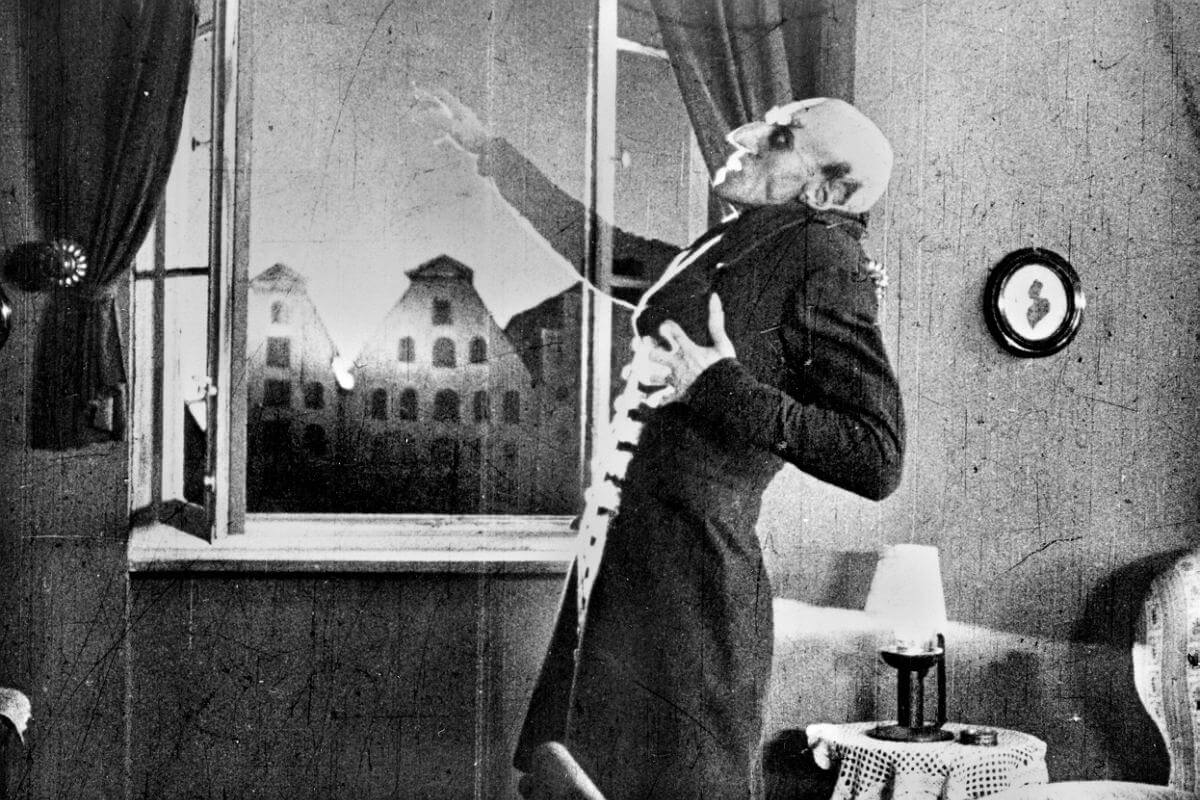

The birth of a demon - Friedrich Murnau

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau merely flirted with expressionism. The idea of creating reality in unreal spaces was not close to his heart. Murnau preferred to utilize the possibilities offered by outdoor shooting. This led to the creation of the first film that tells the story of a Romanian bloodsucker ruling an ancient castle hidden within the Carpathian borders.

Nosferatu – A Symphony of Horror made its debut on silver screens a month before Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, in 1922. Unable to secure the rights for an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s novel, Murnau decided to sidestep copyright regulations. As a result, the novel’s Count Dracula transforms into Count Orlok on celluloid, the titular Nosferatu – and a similar situation occurs with the names of other characters. The storyline itself also undergoes significant modifications, with the character of Dr. Van Helsing, for example, being limited.

Murnau narrates the story of a young man who sets out on a journey to the castle of the old count, driven by a desire for wealth. He leaves behind his beloved in his hometown, who, out of longing and fear of losing her lover, succumbs to madness. Meanwhile, the young man arrives at the stone castle, which surely remembers the times of medieval battles. It turns out that the surname Orlok instills a near-panicked fear among the villagers from the nearby village – supposedly, the castle’s owner is a legendary bloodsucker. Skeptical of supernatural phenomena, the young man ignores the warnings of the locals and ventures to meet Orlok. By the time he realizes that the count is not a normal man, it is already too late. The vampire signs a contract that makes him the owner of the property adjacent to the young man’s house. In the meantime, Orlok notices a likeness of the young man’s beloved placed in a gold locket. The bloodthirsty vampire has only one goal from that moment: to taste the blood of this beautiful woman.

Murnau’s expressionist concept is realized in the screenplay as an escape from reality into the realm of fantasy. Formally, the director treats expressionism quite selectively, employing ubiquitous contrast and demonic makeup that transforms Max Schreck, the actor portraying Orlok, into a terrifying creature.

Schreck’s portrayal was so convincing that even to this day, a legend circulates that he was an actual vampire. The claim states that on-screen, he was himself, and he assumed an actor’s mask off-screen, pretending to be human. The legend is further fueled by the significance of the actor’s name, which translates to “fear” in German, and the mysterious biography of the actor portraying the vampire. Today, we know about the life history of the German actor (he was associated with Max Reinhardt, similar to the expressionist Golem), but should we unconditionally believe it? Perhaps Schreck played the role of a human so convincingly that he managed to deceive even his biographers?

An homage to this legend was paid by American filmmaker E. Elias Merhige in 2000, with the creation of Shadow of the Vampire. The film, utilizing fragments from the 1922 Nosferatu, narrates the story of the making of Murnau’s film. It portrays Max Schreck as a bona fide vampire who manipulates the director at every step of the film’s production, demanding the blood of the actress portraying the real estate agent’s wife as payment for his role.

This is what Murnau left us with in terms of expressionism – of course, within the stylistic confines of the movement. A somewhat average story with characters who somewhat resemble those we will encounter in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis a few years later. Characters without deep psychological dimensions, naive. All this is flavored with a spine-tingling legend that still captivates the imagination of the viewer. One might say that Nosferatu is more the work of Max Schreck than of Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau himself, who would realize his directorial talent in the Kammerspiel style, creating masterpieces like The Last Laugh (Interestingly, the script for The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari was also written by the author of The Last Laugh, Carl Mayer).

In longing for Caligari – Paul Leni and his cabinet

At the same moment when the monumental triumphs of The Nibelungs, propagating the expressionist poetics according to Fritz Lang’s recipe, were celebrated, a film with visual references to Caligari burst onto the screens. The initiator of this whole commotion was Paul Leni, a director in his early thirties from Stuttgart.

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari serves as a synthesis of two expressionist ideas – the cubist fantasies of Wiene are merged with the narrative structure once written by Thea von Harbou. It acts as a common denominator between The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and The Weary Death. Additionally, it brings together the most characteristic actors of the expressionist era. Emil Jannings (Porter from the Hotel Atlantic, The Blue Angel), Conrad Veidt (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Hands of Orlac, The Student of Prague [1926]), and Werner Krauss (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Rails, The Student of Prague [1926]) stand side by side. Thus, Waxworks could be referred to as a sum of expressionist diversities.

Similar to The Weary Death, the story unfolds on four levels. However, the candles symbolizing human souls are replaced by three wax figures. The stories will revolve around these figures, devised by a young novelist hired by the cabinet owner to enhance the stories of his wax subjects. The first exhibit is the likeness of Sheikh Harun al-Rashid (Emil Jannings), so the initial story adopts the backdrop of his homeland of exotic spices – a variation borrowed from Fritz Lang’s film. The second figure represents Tsar Ivan the Terrible (Conrad Veidt), who, consumed by his bloodlust, falls victim to the witchcraft snares set for his prey. The final exhibit is an exact replica of the infamous murderer, Jack the Ripper (Werner Krauss). His episode was not inscribed on parchments; it was a dream-like creation of a tired writer and served as a bridge between the works of Wiene and Lang.

Despite copying the precedents’ patterns, the film remains significant as it amalgamates everything that expressionism brought. It harmonizes Wiene’s cubist-geometric fantasies with the brilliant use of spaces and mastery in manipulating artificial light, characteristic of Fritz Lang. The enchanting oriental tales of the era contrast with contemporary Germany. Demonic characters like Caligari, Nosferatu, and Rotwang are linked to stereotypical personas like Jack the Ripper and Ivan the Terrible. Probably intentionally, the entire piece is united by its cast. By placing the three titans of acting side by side – who, no matter how you look at it, play the roles of monuments, statues they have erected with their unforgettable performances even in their lifetimes.

The fall

The era of silent film was coming to an end, and in 1927 in America, the premiere of the first partially sound film took place – The Jazz Singer. Sound killed silent cinema, which was just beginning its artistic revolution. The advent of sound film, along with changes in the mentality of the German citizens, also marked the end of expressionism.

Only two titles were able to realize the principles of the movement on a tape enriched with a melodic line. As we know, the first of these was M – The Murderer, which cultivated the traditions initiated by Doctor Mabuse. The second one, The Blue Angel, besides the magnificent performance of Emil Jannings, also gifted the cinema something more – the wonderful Marlene Dietrich. Let’s start with this film, as it premiered a year before Fritz Lang’s movie.

Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel has a subtitle – The Fall of the Tyrant. This tyrant is a high school teacher (played by Jannings), who among his students does not enjoy a favorable reputation. One day, disgusted by the demoralizing influence of a cabaret star (played by Dietrich) on the town’s youth, he visits her with complaints. This visit becomes his downfall; seduced by Dietrich’s predatory sexuality, he spirals down to rock bottom. The respected profession of a teacher turns into a comedic charlatan’s costume, and his scholarly eloquence transforms into the terrifying crowing of a rooster.

The Blue Angel is not just about Dietrich’s sensuality; it’s also a metaphor for contemporary Germany. Beneath the layers of deep faith and rigorous adherence to rules, true emotions are brewing within the society, emotions that according to Nietzsche or Bergson determine our essence. The Blue Angel is also the perfect contradiction to the Hollywood cinema of the time, which from the 1930s onwards became governed by the Hays Code, blocking any manifestations of on-screen sexuality. It’s precisely this sexuality – Dietrich’s incredible allure – that captures our attention. Could the scene where she sits provocatively with her legs crossed not have been an inspiration for Paul Verhoeven and the famous scene from Basic Instinct?

Lang’s penultimate film made within the territory of Germany departs from the style he employed since the premiere of The Nibelungs. The director abandons monumental tales from ancient Germanic times and apocalyptic visions of the future, returning to themes somewhat initiated in 1922 by his Doctor Mabuse. He creates a suspenseful crime story, which is based on real events. He crafts a film that, between the lines, poses a serious question to the audience – how should mentally ill individuals be treated when they pose a threat to the normal people? Should they be judged like mentally healthy individuals?

M presents the story of a mentally ill outsider who takes the lives of innocent children in the winding alleyways. Ultimately, he is found, not due to the faulty police apparatus, but thanks to the joint effort of society and the mafia organizations, who pursue the perpetrator because his crimes mobilize the local security forces. In a confrontation with the gang leader tasked with extrajudicially executing the killer (the role of the mafia boss is played by Gustaf Gründgens, the same actor who in a few years will portray Mephistopheles in Nazi Germany’s theaters and will become the subject of István Szabó’s film), the question of the moral foundations that could justify such an act arises. Soon, Adolf Hitler will resolve the issue of mentally ill citizens with his T4 program.

M, in accordance with expressionism, is politically engaged – it is, to some extent, a critique of the sluggishness of the police force and a critique of the legal system. Like a magical mirror reflecting the moods prevailing in Germany at the beginning of the 1930s, it is full of anxiety, difficult questions, and dynamic changes. And ultimately, it is fascinated by the secrets of the human subconscious, once again using a deranged person as a creative tool, a fetish of expressionist authors.

Thus, within a decade, German expressionist cinema was born amidst post-war troubles and died under the pressure of sound cinema and the impending Nazi doctrine. However, it did not perish completely; its spirit continues to haunt the realms of the tenth muse.

Conclusion

Motifs from expressionist films appear in the music videos of the most famous rock bands. Even the great Queen uses scenes from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. The same apocalyptic vision of the future becomes an inspiration for Japanese director Rintaro, who in 2001 creates his vision of a city-machine. Another prominent German director, Werner Herzog, pays homage to F.W. Murnau in 1979 by creating a new version of Nosferatu, employing expressionistic elements. The magical, unreal sets of Tim Burton strongly reference the fantasies of expressionist creators. The city in which Edward Scissorhands must live is wonderfully unreal, just like the cities of expressionists. Gotham City from Burton’s version of Batman is almost a replica of the future city created by Fritz Lang. David Lynch skillfully employs expressionistic techniques in his feature debut, the enigmatic Eraserhead. The champion of Manhattan himself, Woody Allen, creates an homage to the style with Shadows and Fog in 1992. From expressionism arises film noir, influencing directors like Kurosawa and Hitchcock. In the end, expressionism is the father of horror narratives; without it, horror might have emerged only after World War II and could have taken a completely different direction.

Let us conclude by adhering to the principles of this extraordinary doctrine. Expressionism may have died in physicality, but its spirit has transitioned to a realm of reality that continually oscillates on the border of our material world. Some individuals can draw from this realm, aided by intuition and the subconscious. They think with their hearts, not their minds. They are the chosen ones, and only they can resurrect the spirit of expressionism so effectively that it once again takes our breath away.