DAISY TOWN. Lucky Luke embodies the Spirit of the Era

Across the prairie, stagecoaches roll forward. A line of caravans rushes nowhere through a desolate wilderness. All around, only swirls of desert dust rise, the scorching sun beats down from the sky, and there’s no sign of any river flowing nearby. Yet American pioneers are tough, filled with determination, pride, and resourcefulness. Along with their families and all their worldly possessions, they traverse the Wild West to find a place to call their own, to build homes, and to settle. Their bold march is halted by nothing less than a daisy (the titular flower), innocently growing in the middle of nowhere. A quick decision is made: this is where we’ll live! This is our place on Earth. Beside the daisy, they plant a sign bearing the name “Daisy Town.”

There’s nothing left to do but roll up their sleeves, get to work, and start building. Before our very eyes, a town takes shape—not just a backdrop for Lucky Luke’s adventures, but a full-fledged character and the true centerpiece of René Goscinny’s animated film. With remarkable creativity, the Frenchman adapts Maurice de Bevere’s comic (which the two later co-created) into the cinematic medium. The result is a rich, multifaceted, and distinct piece of cinema.

The creators take a loose approach to the Western genre, viewing it with a playful wink. The film’s opening sequence, depicting the construction of Daisy Town, introduces various locations strongly associated with the genre. The first building erected is, naturally, the hub of social life—the saloon. But it doesn’t appear in the usual way; instead, it’s cut in half, cleanly sawed down the middle. Before its second half is added, a drunken Mexican slumps by its entrance. Nearby, a funeral parlor emerges (its grim owner eagerly watching for victims of gunfights), alongside a bank that attracts robbers like a magnet, and a jail complete with a tunnel already dug for an escape. The town of Daisy rises proudly before the viewers’ eyes, accompanied by a joyous choral “Hallelujah,” while a white dove flies above the buildings, blessing this act of creation.

At times, Daisy Town transcends mere modernist parody. A particularly significant moment occurs when one of the Dalton brothers—the notorious villains tormenting the town—tries to persuade local Native Americans to join forces with them, plunder the town, and drive out its residents. Goscinny then takes us far into the future, showing the inevitable course of events. The small settlement will expand, consuming more and more territory, regardless of whether Native Americans live there or not. If Daisy Town isn’t destroyed, the Native Americans face extinction. During this sequence depicting the town’s expansion, the creators first draw ever-growing networks of railways and roads, along which cars race. Eventually, the animation gives way to shots of modern, sprawling American cities. This Belgian-French production thus blends humor with a touch of reflection on the consequences of civilization’s progress—the beauty it brings and the destruction it leaves in its wake.

Despite its brief 70-minute runtime, René Goscinny’s film offers a fascinating exploration of the themes, motifs, and characters of Western cinema. Each element of this world is presented vividly, employing caricature, stereotypes, and exaggeration. The Dalton brothers, for example, are comedic clones differing only in height and defined by their perpetual criminal scheming. Goscinny also finds time for a decisive mayor in a tuxedo, distrustful Native Americans, and a spectacular cavalry charge. The film features a gunfight on the main street (preceded by the rhythmic closing of window shutters), a bank heist, and gold prospectors. Daisy Town offers a comprehensive look at the pop-cultural image of the Wild West while capturing the vivid details and dynamic intensity of this world.

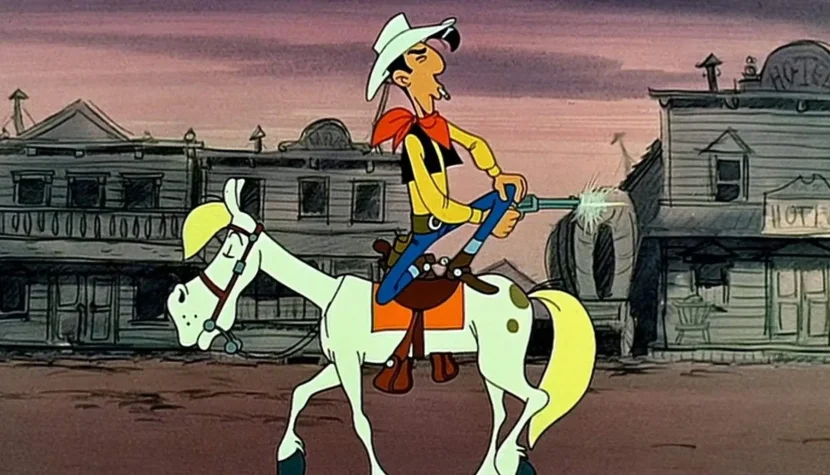

What role does Lucky Luke play amid all these attractions? Primarily, he’s an observer, sometimes a guide, and when necessary, an active participant in the unfolding events. The titular cowboy shifts roles throughout the film—at times a free rider, at others a sheriff, and finally the last just man—fulfilling the archetypal journeys of Western protagonists. Lucky Luke embodies the Spirit of the Era, both a product of his time and a romantic dream of it. He is a character who can exist only within the framework of this vividly imagined world.

In the lyrical finale, only Lucky Luke remains in Daisy Town. The town’s founders quickly pack up and move on, tempted by the promise of newfound gold riches elsewhere. Behind Lucky Luke, Daisy Town stands abandoned. Our hero lingers by the town sign, where the daisy from the film’s opening still blooms. The cowboy picks it and pins it to his horse’s mane. Then, at a slow pace, he rides off into the sunset. A quintessential scene, yet imbued with the power of an iconic image.