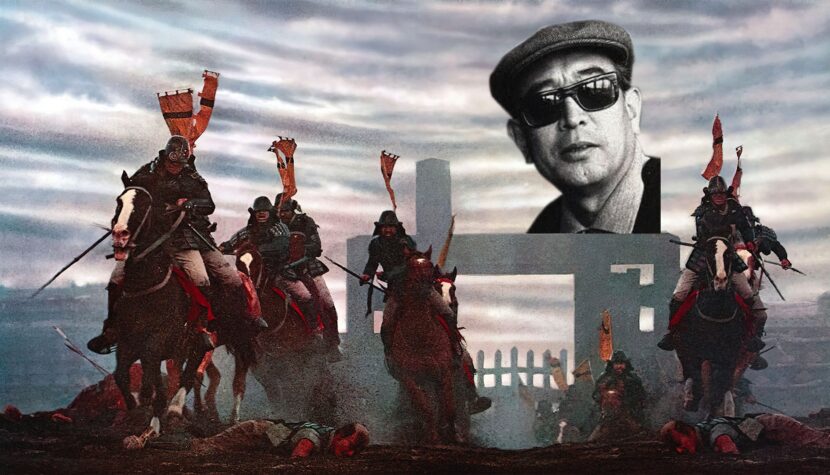

AKIRA KUROSAWA. Eight masterpieces you MUST WATCH

The world audience got to know him in 1950 when his film Rashomon was screened at the Venice Film Festival. The film was awarded the Golden Lion, the festival’s top prize, which was mentioned in the Japanese press with just a brief note. His directorial career spanned six decades, and each of them offers intriguing works. Many of his films are now considered classics of cinema. He was a painter, screenwriter, editor, and director. He was referred to as The Wild One and The Emperor. Akira Kurosawa and his eight most important films.

Seven Samurai

Arguably the most famous film by the director. It’s one of the few titles where the term “epic” fits perfectly and is not an exaggeration. Kurosawa stretches his narrative over more than three hours – giving us ample time to get to know and love the titular characters. Set against the backdrop of feudal Japan – the director’s favorite period – the story revolves around sacrifice, honor, and brotherhood. Impoverished villagers from a small village plagued by bandits seek help from samurai. The warriors agree to defend the villagers, fully aware that they won’t be able to expect gold, splendor, or glory. An uneven battle ensues, featuring spectacular fights, romance, and several moments of humor. Despite its grand scale, Kurosawa keeps the story grounded, preventing lofty statements from falling into banality or kitsch. Seven Samurai is above all a magnificent showcase of direction and editing, laying the foundation for modern action and adventure cinema.

Related:

Ikiru

Reportedly, Kurosawa considered this film his masterpiece. A personal narrative steeped in existential unease reminiscent of Sartre or Camus. Kurosawa has been criticized for Ikiru, saying it’s too sentimental, teary, and ultimately straightforward. However, it’s precisely from this simplicity that its beauty and strength emerge. Known for his grandeur, lavish set designs, and opulent costumes, the director opted for a more modest means of expression this time. The film relies heavily on the strong performance of one of Kurosawa’s regular collaborators, Takashi Shimura, whose gentle face and unassuming demeanor reflect the state of his character.

Dying from cancer, a bureaucrat decides to do something valuable in the last days of his life. He begins building a playground for children, aiming to give his life meaning and die with the knowledge of leaving a mark behind.

Stray Dog

A clever and appealing blend of genre cinema and socially engaged filmmaking – essentially what Kurosawa excelled at. A young police officer (Toshirô Mifune) and his older mentor (Takashi Shimura) delve into the world of post-war Japan’s criminal underworld. The intrigue begins with the theft of police weapons, but this incident is just the starting point for a much broader and deeper reflection on society’s condition. Stray Dog aligns with the poetics of crime films, from which Kurosawa draws narrative and dramatic solutions. Often considered a Japanese film noir, this description isn’t far from the truth, given how much of his work is owed to the director’s fascination with the West.

Rashomon

The title that brought Kurosawa international fame and recognition through its victory at the Venice Film Festival. Interestingly, Kurosawa wasn’t present at the ceremony because the film didn’t receive recognition in Japan. The unconventional narrative structure, captivating direction, attention to detail, painterly frames, and Toshiro Mifune’s expressive, animalistic performance turned out to be a mix captivating enough to draw the eyes of cinephiles worldwide to the work of the Japanese director. Rashomon presents four perspectives on a single event. Four facets of the truth, or perhaps simply – four truths? Kurosawa poses questions about the meaning of one of the fundamental concepts and examines human morality put to the test. And he does so in his style – that is, by utilizing the possibilities of the cinematic medium in every conceivable way. Camera work, framing, editing, lighting – everything in Rashomon sets a standard to be emulated.

Throne of Blood

The director’s first (of three) forays into film adaptations of Shakespeare. The basis of the screenplay was one of the most renowned texts from the Stratford master – Macbeth. Kurosawa transposed the action from medieval Scotland to feudal Japan, skillfully transferring motifs from Western culture onto the canvas of Eastern civilization, finding coherence and unity at the juncture of two religions. However, Throne of Blood is not a philosophical treatise; it’s cinema – visceral and vivid. The dramatic action reaches its peak of tension thanks to the extraordinary directing, staging, and editing skills of the creator. The concluding sequence with the deluge of arrows burying the panicked Mifune is one of those images that remain with a person for life.

Red Beard

The last black-and-white film by Kurosawa and also the final movie in which Toshirô Mifune appeared – previously his regular actor, with whom he collaborated sixteen times. The titular Red Beard is a young doctor who is assigned to work in a hospital for the impoverished. Once again, the director allows the audience ample time to get to know the characters and develop an attachment to them. The three-hour-long experience is rich with subplots, secondary characters, dramatic (perhaps occasionally overly dramatic) scenes, all of which contribute to a bitter, melancholic reflection reminiscent of the works of world literature classics like Knut Hamsun or Fyodor Dostoevsky. It seems that Red Beard remains one of the most underappreciated works of the Japanese master, which is why it’s worth revisiting.

Dersu Uzala

One of the most remarkable features of Kurosawa’s work is its tendency to bridge divisions. This is also true in the case of the Soviet-Japanese co-production. The epic adventure film tells the story of an old hunter, the titular Dersu Uzala – a Nanai, a representative of the Tungusic peoples who inhabit Siberia, and a Soviet military officer and explorer – Captain Arsenyev. The scientific expedition led by the latter seeks Dersu’s assistance in navigating the inaccessible and dangerous terrain of the taiga. Initially, the Russians view the Nanai as an eccentric, peculiar old man, but as the story unfolds, they begin to recognize his profound wisdom, incredible intuition, and skills derived from a lifetime of living in the rugged wilderness. Captain Arsenyev and Dersu form a deep friendship, and their bond lasts until Uzala’s death.

The film is based on a true story, recounted in Arsenyev’s expedition journals. Film lore even suggests that the character of Yoda in The Empire Strikes Back was inspired by the titular character of this film – a diminutive figure combining quirkiness and unparalleled wisdom.

Ran

Kurosawa’s magnum opus. A film steeped in the nihilism and darkness that accompanied him in the later years of his career and life. Despite the Oscar success of Dersu Uzala in 1975, which was made “on commission,” the director faced personal and professional challenges. He struggled to secure finances for his subsequent projects, battled alcoholism, and attempted suicide in 1971. Nevertheless, he found the strength within him to create his final masterpiece in his career. Ran, meaning “Chaos,” was released in 1985, just a few months after the death of the director’s wife. In this film, Kurosawa returned to his fascination with Shakespeare (as well as Western civilization), adapting his play King Lear into the context of Eastern culture, Buddhism, and traditional Japanese art.

Ran is, if one could use such a term, a total film, wherein you can find a culmination of the artist’s creative and personal life, and witness his directorial talent in its full glory. Suffice it to say that the film’s storyboard was personally created by Kurosawa (who was a trained painter) – each frame was initially painted on canvas. It is an absolutely essential viewing for every self-respecting cinephile.