Everything there is to know about GERMAN EXPRESSIONIST CINEMA

As the 19th century was coming to an end, as doubts slowly crept in about the old man who had so generously endowed our civilization, whether, in his final days, he could bestow upon us anything more, a group of women marched out of the Lyon factory with smiles on their faces. There would be nothing unusual about this if this particular procession had passed through the square in front of the factory gates. However, their journey took place in a completely different location and, lo and behold, without their direct participation. The female workers were, in fact, marching between the frames of a celluloid strip, which, thanks to a certain magical box created by the manufacturers of photographic materials, the Lumière brothers, came to life and started moving amidst the solid walls of the Indian Salon. The 19th century amazed us once again, assisting in the birth of another muse: in 1895, it gifted us with cinematography.

The birth of a titan - Fritz Lang

The Golem marked the last interpretation of the Jewish legend of the Golem (in Wegener’s rendition), and after that, a brief silence fell over the world of German expressionist cinema. This silence was shattered by the expressionist hurricane brought about by the entrance of Friedrich Murnau and Fritz Lang onto the German scene.

Fritz Lang, after producing a few less captivating titles such as Spiders Part I: Adventure on the Golden Lake (a literal translation from German), appeared on the silver screens in 1921 with The Weary Death, written by his future wife, Thea von Harbou. In my subjective opinion, this fairytale represents the peak achievement of both the director and German expressionism.

The film tells the story of a young girl who, accompanied by her beloved, arrives in a small town where another stranger resides—a man with a sad face, eyes where the will to live has extinguished, dressed in black robes. Tempting the local upper classes with the jingle of gold coins, he buys consecrated burial land and erects a wall around it, a wall with no entrance. Only he can open the gate that leads to the hidden garden behind the stone enclosure. This newcomer is Death, and the garden is his kingdom, and the young man becomes his next lamb. The girl cannot come to terms with the departure of her lover; she loses her mind in despair. She grabs the Holy Scripture and stumbles upon a quote: “Love is as strong as death.” On the wings of this quote, she crosses the wall that separates her from the realm of Death and faces him. Death makes her realize that it is not up to her, but up to God, to decide who should end their earthly stay. However, he allows the girl to attempt to rescue her lover. He shows her three burning candles, symbols of human souls, and tells her that if she saves even one of them, she will return life to her beloved. Each flame represents a different story, a story of unfortunate love. The first transports us to mythical India, the second to Venice, and the third to the Far East, distant Japan.

Lang abandons the madness style employed by Wiene, to some extent perpetuated by Wegener, and revived a few years later by Paul Leni in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. For him, fulfilling the expressionist doctrine is important not artistically (in a painterly way), but ideologically. He conveys characteristic expressionist themes in a somewhat primitive yet beautiful manner and throws distinctive slogans.

He transports us to a world that breathes the same air Goethe once did. He upholds the tradition of German Romanticism, demonstrating the power of love; equating it with death, he makes us realize that love is the meaning of our life. He doesn’t belittle death itself, its power, because in the ending, he indicates that escaping fate is unavoidable, and the only way to overcome death is to reside in its garden. He criticizes the materialistic approach to life held by those in high positions. By naming his characters with universal titles—Doctor, Mayor, Official—he launches an attack on the bourgeoisie, who prefer to sit in bars and exchange sacred grounds for a handful of gold coins rather than engage in genuinely important matters (an expressionist critique of capitalism).

He transports us to the Far East, which for expressionists was humanity’s cradle, a place where humanity, devalued by war, could be reborn anew. There, all aspects of life are determined not by the desire for profit, but by faith. According to expressionists, combining Far Eastern ideas with Western civilization’s achievements would create an ideal society.

Lastly, a seemingly random scene, perhaps an attempt to criticize the contemporary world—a battle between two roosters on the floor resembling a map of our globe. They fight without reason, without purpose, much like how Lang fought on the battlefront three years earlier during World War I.

Lang portrays Death itself in an incredibly original way. As the title suggests, Death is weary of witnessing the suffering caused by its visits. It is tired of people demonizing it for following the orders of the same God to whom they fervently pray. It is a tragic figure, condemned to loneliness simply for being faithful to the Creator.

Just because the director shies away from the dreamlike decorations created by the “Der Sturm” group, it doesn’t mean his films lack captivating visuals. On the contrary, Lang plays with light and incorporates beautiful hints of what we now call special effects. The use of “Méliès-like” tricks allows the German creator to demonstrate in the 1921 film, a white horse galloping across the sky (in the Japanese story), a soul leaving a man’s body (main German story), a miniature army emerging from a sorcerer’s kimono (Japanese story again), a flying carpet, and an intelligent parchment (once more, a story from the Far East). Watching these types of shots revives the sentimental side of our souls. We sense that we are engaging with cinema, where magical events were brought to life through human hands, not lifeless integrated circuits.

Fritz Lang, while embodying the expressionist doctrine, creates one of the most beautiful European fairy tales, which unfortunately falls into obscurity under the weight of his most famous work, Metropolis. However, before we delve into the world of the 20th-century “city-machine,” let’s pause for a moment to consider his two earlier films – Doctor Mabuse and The Nibelungs.

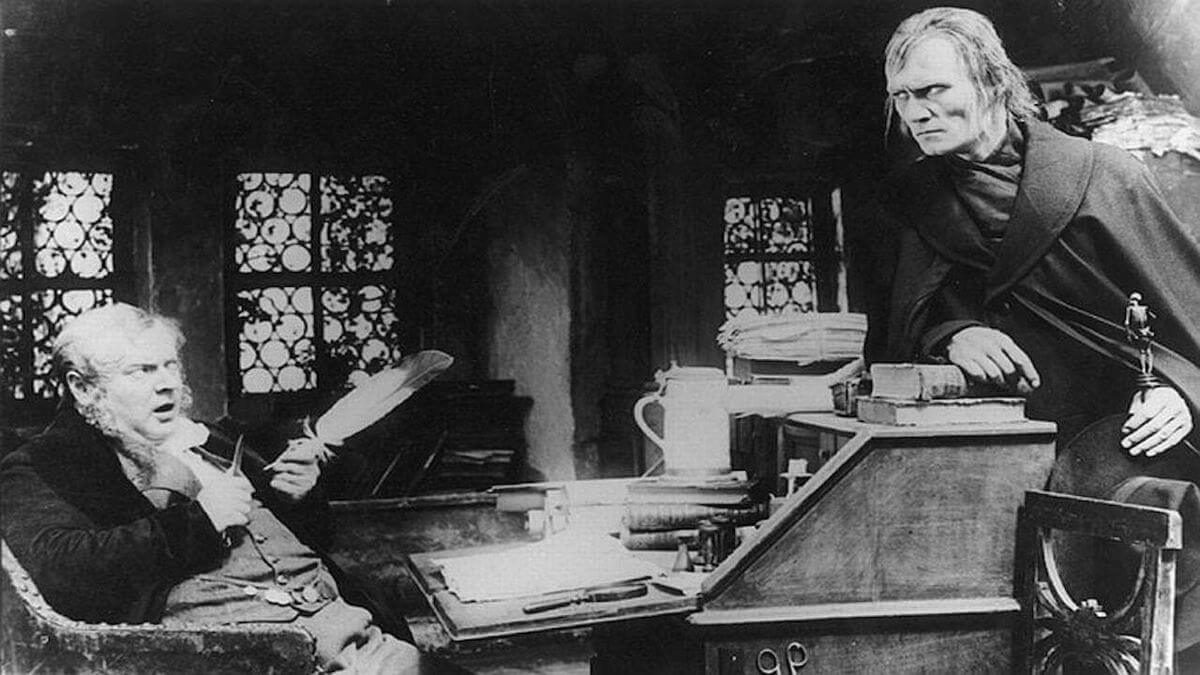

The story of Mabuse became a cinematic hit, and its sequels continued until the 1960s. However, only the first part of the series, premiered in 1922, was created in the expressionist style. Once again, Lang brings to life the script written by his wife, this time transporting us to a city where Inspector Norbert von Wenck battles the demonic leader of the local gang, the titular doctor. The entire story is an adaptation of a novel by Norbert Jacques.

In this film, Lang does not distance himself from the fascination with the expressionist movement, incorporating into his cinematic craftsmanship a character who can induce people into a hypnotic trance using his psychic abilities. This man uses his extraordinary powers to fulfill his most secret desires – the desire for murder, the desire for profit. Ultimately, Mabuse is defeated by his own mind, which refuses to obey him when the ghosts of his victims appear before him. The doctor ends up in a psychiatric hospital, which becomes the setting for the next film in which he appears. Throughout the film, the influence of Freud’s theories is evident, and Lang believes that the non-material world somehow still accompanies the reality in which we exist. The demonic figure of Mabuse strongly resembles Caligari, also a doctor. The only difference is that Lang’s character uses extraordinary psychic abilities within his own body, while Caligari exploits the psychic predispositions of his sleepwalking victim. The struggle against the mad doctor, the ending within the walls of a madhouse, the demonic doctor – did Fritz Lang commit something akin to plagiarism? Or did the scriptwriter of Wiene’s film not acknowledge the influence of Jacques’s novel?

Doctor Mabuse is also one of the precursors of the crime thriller, effectively developing the patterns initiated by French stories about Fantomas. Aggressive editing and excellent chase and panic scenes contribute to its undeniable success. However, beneath the guise of sensational entertainment lies an attempt to depict post-World War I Germany, where doubt and anarchy roam the streets much like they do on the film reel.

After Mabuse, and before the leap into the future, Fritz Lang embarks on a journey to the past. He visits an era where Germanic tribes are triumphant (unlike the Germany of his time) and presents us with the 12th-century tale of the Nibelungs. He divides this tale into two parts, both closely connected in plot; both parts premiered in 1924.

The first part, The Death of Siegfried, narrates the love between the titular hero and Kriemhild, a love that is interrupted by the death of the valiant lover. Young Siegfried, embodying all virtues (emphasized by the contrast between his white attire and the clothing of his tormentors), encounters a fire-breathing beast as he journeys through a magical forest. Swiftly drawing his sword, he ends the life of the terrifying dragon. Suddenly, a skylark speaks to him from a nearby branch, revealing that bathing in the dragon’s blood will make his body invulnerable to sword strikes, arrowheads, and spears. Following the advice of the avian messenger, the youth decides to take a bloody bath. However, as the dragon’s dying body writhes in its final agony, a leaf falls from a tree and lands on Siegfried’s shoulder. This becomes Siegfried’s “Achilles’ heel,” into which the morose warrior Hagen – a dark figure clad in black armor – thrusts his sharpened spear. The murder is revenge for Siegfried’s assistance to King Gunther, enabling him to win a contest for the hand of the Icelandic ruler Brunhild. Siegfried’s aid is motivated by his love (Gunther’s marriage to Brunhild was a condition for Siegfried’s union with Kriemhild), but Brunhild views it as dishonorable.

The second part, Kriemhild’s Revenge, sheds its fairy-tale veneer and transforms into a dark spectacle of revenge. Kriemhild, in pursuit of her plans, remarries. This time, she weds King Etzel of the Huns. However, Etzel does not agree with his new wife’s intentions, prompting her to take matters into her own hands. Kriemhild seizes Siegfried’s sword and unleashes a bloody massacre at her wedding feast, during which her lover’s murderer, the brooding Hagen, and King Gunther are among the victims.

The story of the Nibelungs has been one of the most popular Germanic tales for centuries, and its interpretations include Wagner’s famous tetralogy The Ring of the Nibelung and Friedrich Hebbel’s dramatic work, which was performed on German stages until 1914. The wife of Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou, appeared in Hebbel’s version, and the classic, unadulterated 12th-century spirit of the Nibelungs, unaffected by Wagner’s opera, was well-known to her. This familiarity was helpful when creating the screenplay for her husband’s film. The potential of the ancient Germanic legend, combined with Fritz Lang’s artistry and the production power of the “Decla-Bioskop” and “UFA” studios (the two largest German studios), resulted in the creation of a monument of German silent cinema.

Lang enclosed the entire endeavor within the walls of an impressive atelier, which, thanks to exquisite set designs – not the cubist phantasms in the style of Wiene, but Lang’s characteristic style – transformed into a fairy-tale world from the ancient Germanic tales. The director skillfully utilized the possibilities offered by artificial lighting, thus realizing one of the fundamental principles of expressionist visual arts – an affinity for contrast, which is also used in character portrayal. Thirty years before the birth of Japan’s Godzilla, Lang confronted the audience with a fire-breathing dragon, a challenge that young Siegfried must face. Moreover, the beast doesn’t look bad at all; compared to the monsters from contemporary “B-movie” productions, it hardly differs. The dragon is by no means the only “gem” to be admired in The Nibelungs. Kriemhild’s dream is splendidly realized, the animated scenes are interesting, but all of these pale in comparison to the brilliance emanating from the ingenious set designs of Hunte, Vollbrecht, and Kettelhut.

A three-year gap separates the premiere of The Nibelungs from the first screening of what is arguably the most famous German expressionist film, Metropolis.

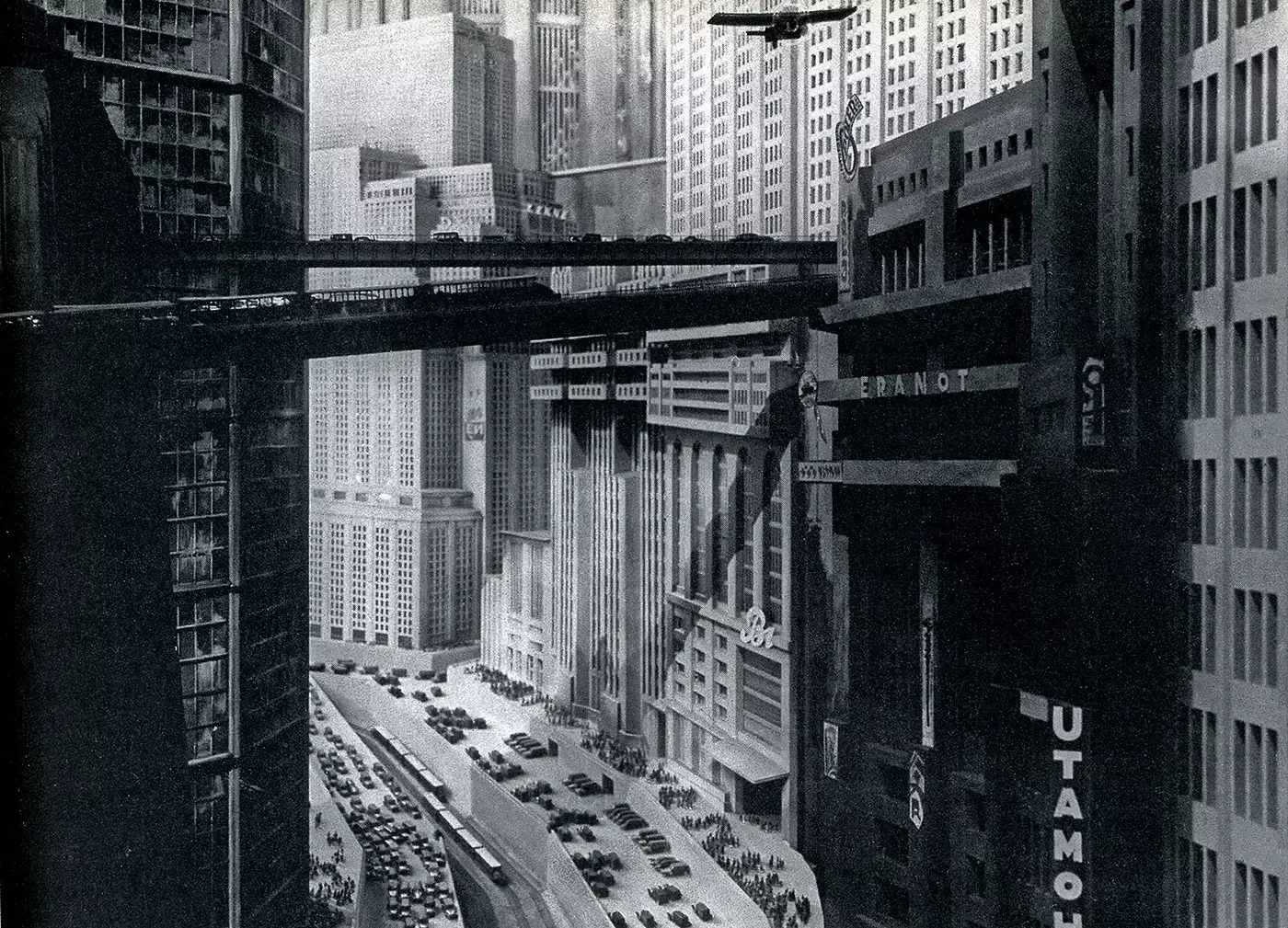

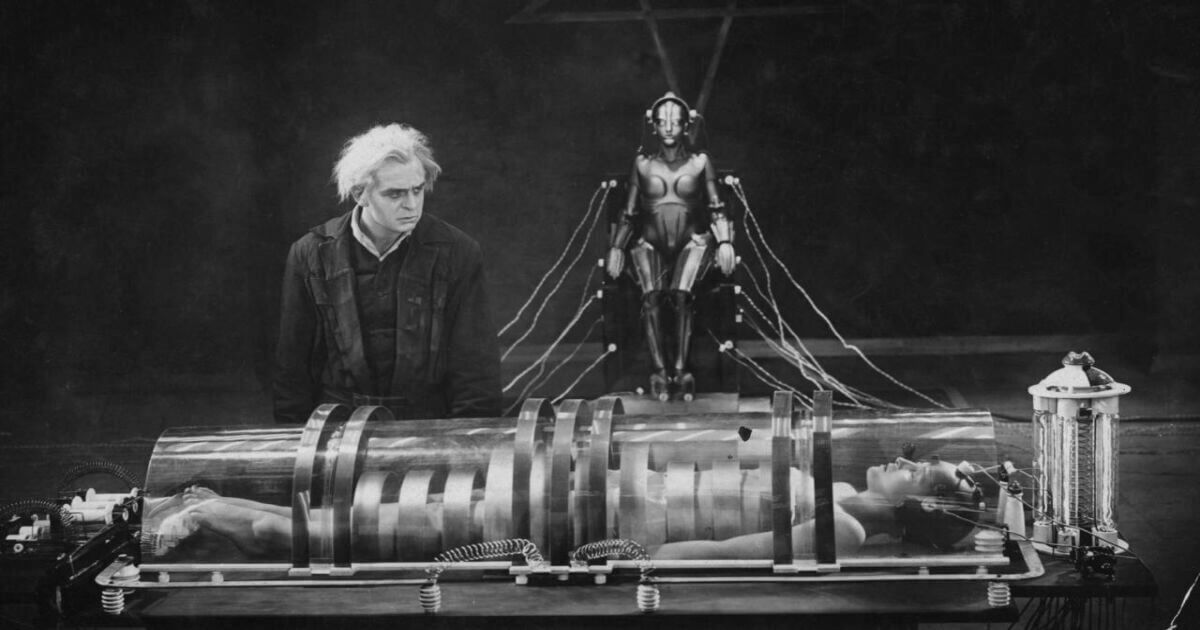

This time, Fritz Lang transports us to the 21st century, depicted on the subsequent frames of the film reel in a truly apocalyptic manner. Society is divided into two classes – the workers, who resemble a horde of genderless creatures servicing the machinery located in the underground depths of the titular megalopolis, and the privileged, inhabiting the upper levels of the city. The world above sea level resembles an earthly Eden, striking us with its whiteness, modernity, and monumentality. The underground resembles dark, narrow tunnels dug by ants between clumps of earth, and the comparison is not coincidental, for the workers, much like these insects, look nearly identical, with the sole exception of Maria, their counterpart to the queen ant. In the eyes of the workers, treated by the privileged as mere cogs in the lifeless machinery, Maria is akin to a prophet in modern times. She preaches the idea that a man will come who will unite the hands (symbolizing the workers) and the mind (symbolizing the privileged) through the heart, creating a symbiotic human organism (symbolizing a harmonious society). Alongside prophets, there usually appear mystifiers attempting to exploit their social position. In Metropolis, the machine becomes the mystifier, crafted with such precision that it cannot be distinguished from a living being.

Wonderfully naive, yet chillingly relevant is the collaborative work of Fritz Lang and his wife. Naive in terms of depicting human relationships, their affinity for contrast, which was already evident during the adaptation of the 12th-century legend, becomes excessively overrepresented in this tale of an apocalyptic future. The distinction between good and evil is no longer based on the color of clothing but rather on the drastically different attitudes of the characters. There are hardly any ambiguous figures, except for the heir of Caligari’s character – the creator of the false woman, Rotwang. As a result of these stylistic choices, the characters in Metropolis become personas who essentially lack psychological depth, instead being given a set of stereotypical character traits. Chillingly relevant is the dependence of humans on machines – isn’t our life already dependent on hundreds of tons of steel machinery today? What was merely science fiction in Metropolis, expressing fear of rampant capitalism and industrial mechanization, is gradually becoming reality. As long as the machine is under human control, all is well, but what will we do when, just like in Lang’s film, the “false Maria” steps among us, looking just like us but lacking what is most essential in a human being – not only according to the expressionists – the immortal soul.

Metropolis emerges from the fear of an uncertain tomorrow in post-war Germany. On one hand, capitalism is galloping ahead, new factories are being established; on the other hand, people suffer hunger as their positions on the production lines are taken by machines. Power is concentrated in the hands of the privileged, capitalists, symbolized by the upper class residing among awe-inspiring skyscrapers. This upper class remains blind to the plight of the gray man, who feeds the ruthless machinery of the underground city-machinery with his own life. In the words of Jerzy Płażewski, Metropolis is not only a masterpiece of set design (extraordinary decorations depicting the city of the future), but also a “Dantean premonition of Auschwitz.” People dressed in identical uniforms, sacrificing their lives during the performance of their Sisyphean labor, waiting for a savior, a new Maria – they are identical to those who tend to the machinery of the underground colossus.

In light of this comparison, it is terrifying to note that a few years later, Thea von Harbou, the film’s screenwriter, would part ways with Fritz Lang and pledge her allegiance to Adolf Hitler’s misguided ideology. Lang, who resisted this new doctrine, had to leave the Third Reich and head to the capitalist America, which, contrary to his expectations, appreciated his directorial prowess, engaging him in the domestic film industry. Before Lang permanently left his homeland, he completed two more productions: his final expressionist film, M (M – Murderer), and the continuation of the Mabuse story, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse. We’ll discuss M in a moment, as alongside The Blue Angel, it was one of the two sound films that adhered to the expressionist principles. For now, let’s rewind a few years back, so as not to forget the man who liberated expressionism from the confines of the studio.