RAN. Akira Kurosawa’s Stunning Masterpiece Explained

He edited most of his films himself, and indeed, he mastered this craft. Skillful editing is not just about perfect cuts, but more importantly, about perfect connections. Finding the point where two separate images touch is extremely difficult. Usually, you have to juxtapose wide and narrow shots, several moving objects, and, above all, maintain continuity in the actor’s performance and expression. The Japanese filmmaker did this masterfully, but his genius went even further. He connected not only moving images but entire cultures.

Between Worlds RAN

With Throne of Blood, Kurosawa proved that he could read and understand Shakespeare, despite the fundamental differences between his own environment and the times and customs of medieval England. Addressing the differences and discrepancies between culture, religion, and philosophy, he created an egalitarian yet distinctly Japanese film. Both Asian and European audiences agreed that this film was one of the best interpretations of Shakespeare in cinema. However, no one could have thought that Kurosawa had not yet said his last word on the subject and that the best was still to come. This occurred in 1985 with the historical epic Ran. This time, the basis of the screenplay was King Lear, considered, like Macbeth, one of the pinnacle achievements of the playwright from Stratford. This story echoes ancient tales passed down in various forms and tells of a father—king who decides to give up his power and wealth to his offspring. In the English original, Lear has three daughters—Goneril, Regan, and Cordelia, the last of whom refuses to serve her father according to his command, incurring his wrath. The father’s adventures, exiled and humiliated by the remaining daughters, form the core of the work, and the side plots, as is typical with Shakespeare, provide a basis for exposing human weaknesses and passions that lead to man’s downfall.

Kurosawa transforms several characters, discards others altogether, and adapts the story—albeit without strict historical context—to the times of feudal Japan, much like in Throne of Blood. However, Ran is a rather loose adaptation. The reference to the Shakespearean drama is clear but does not determine the same conclusions and morals and serves only as a platform to build a much larger and more complicated form. Some see Ran as a summary, a kind of testament to Kurosawa’s work (even though it was not his last film), and it should be considered as such: both as a final attempt to bridge the legacies of different cultures and as the creator’s swan song.

Ran, or Chaos

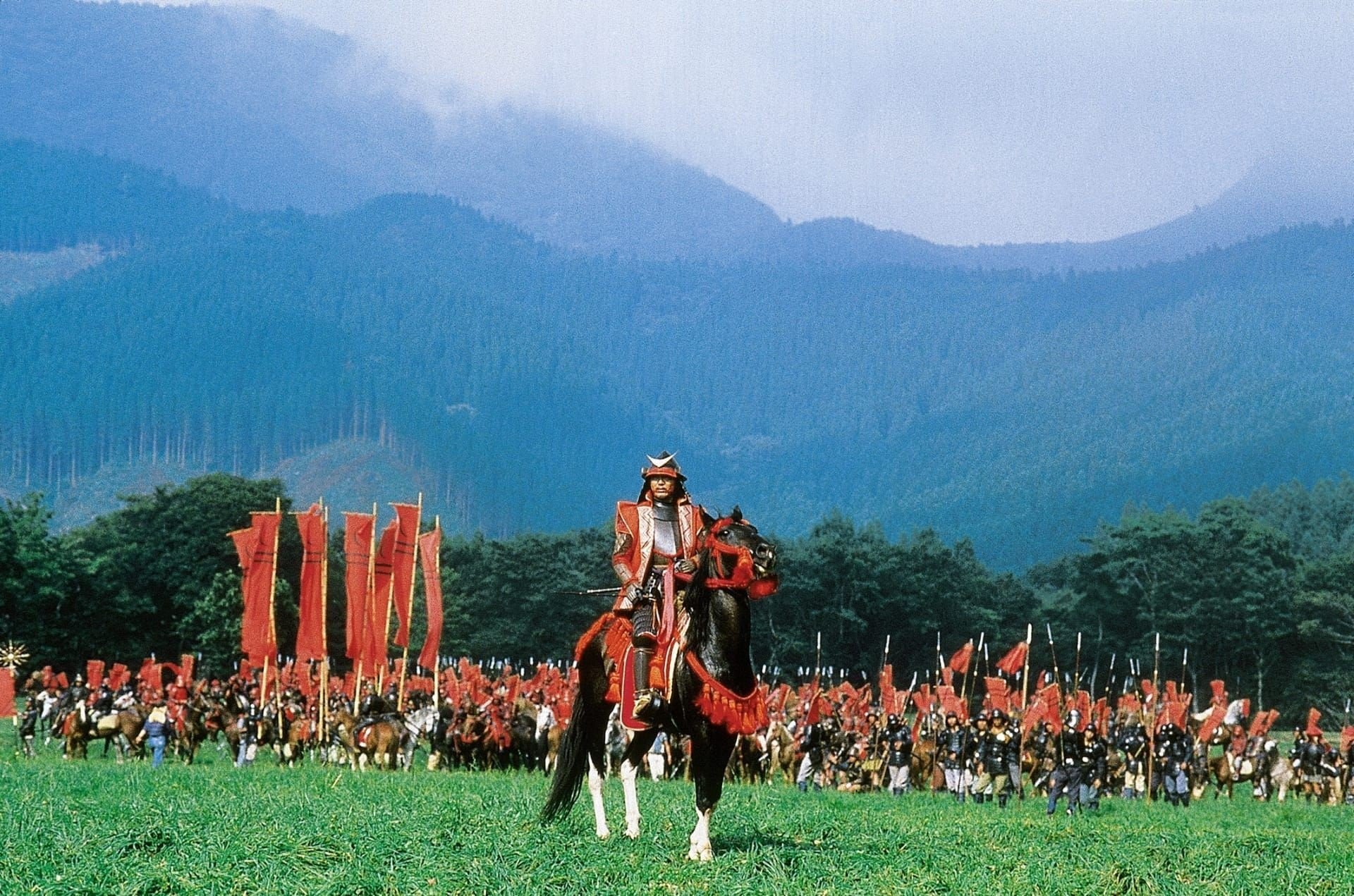

The first shots of the film show samurai against the picturesque backdrop of Nippon‘s green hills. They are waiting for something, looking around carefully. One might even get the impression that they are reacting to the disturbing music accompanying the image (this musical motif, replacing sounds, will return later in the film in a very important sequence). The image exudes unnatural calm. Moments later, game appears, and the armed men start hunting. Chaos ensues…

The old ruler—Hidetora Ichimonji—is tired of fighting and ruling, so he decides to hand over power to his heirs. He distributes his assets among his sons—Taro, Jiro, and Saburo. The first, the eldest, will also be the heir to the throne. Initially reluctant to the proposal, he quickly changes his mind under the influence of his father’s speech. Unlike in Shakespeare, we do not learn the father’s motivations for his choices and do not know what he based his decisions on. However, he emphasizes in his speech that three rulers are harder to break than one. He uses a metaphor for this. He gives each son an arrow and tells them to break it. They do so without any problem, so the father takes three arrows and again tells them to break them. Taro and Jiro cannot do it, but Saburo uses a trick and breaks the bundle. Hidetora feels humiliated by his son, who disagrees with his opinion and will. Saburo is disinherited and exiled, initiating a conflict that ultimately leads to tragedy. The parable of the ruler dividing the kingdom and comparing people to arrows has its roots in Japanese tradition and has no equivalent in the Shakespearean drama.

Karma is… Ironic

Have the gods abandoned us? Where is Buddha? If you exist, hear me! Are you so bored up there that you have to crush us like ants? Is it so funny to watch people cry?—asks Kyoami, the fool. Enough! Don’t blaspheme! It’s the gods who cry. They see how we kill each other since we existed. And they can’t save us from ourselves,—answers Tango, the loyal servant of the ruler. This dialogue, placed towards the end of the film, not only summarizes the events on screen but expresses a thought that perhaps began very early, maybe in Stray Dog, and continued in Throne of Blood. Very Buddhist in essence: evil comes from man, not from a higher power; and human sins will not be punished by God but will return to man according to the law of karma.

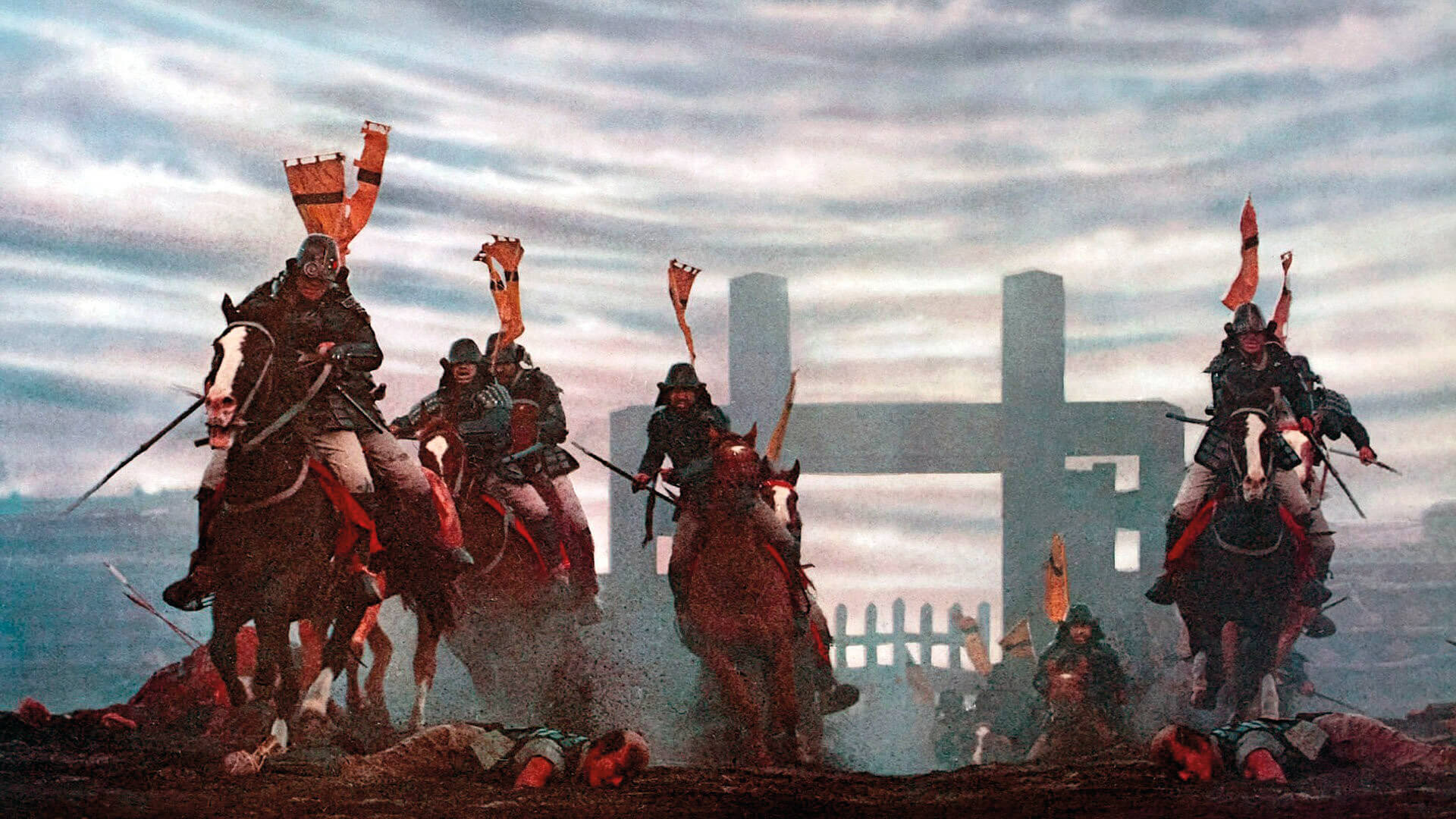

Interestingly, karma returns to Hidetora in a very ironic way. Realizing the evil he has done and the chaos he has caused (Ran means chaos), he submits to fate and voluntarily exposes himself to death. Kurosawa shows this as follows: during the sequence of the great fratricidal battle, Hidetora wanders through the castle. Wherever he steps, dead soldiers fall—from arrows or firearms, in pools of blood and silent spasms (the entire sequence takes place without diegetic sounds, and the only illustration is the disturbing, uneven sound of the flute against the background of drums), yet he somehow avoids death. Having lost his mind, he sits indifferently in the middle of the battle and waits, but even that does not bring the expected result. The end of life would mean the end of suffering for him, but he must still atone for his sins. Therefore, he lives—to see all his loved ones turn away from him or die.

The motif of the separation between man and God is one of the main themes of the film. Kurosawa’s pessimism is felt in the overall tone of the film and in the individual elements. Through the mouths of his characters, he constantly utters fatalistic statements, and visual clues lead to the image of man abandoned by God. In one scene, Hidetora searches the palace for his daughter-in-law—Lady Kaede—and learns that she has gone to pray. The lord then goes to the prayer room, opens it, but it is empty. On the wall hangs only a picture of Buddha. The same picture, which in the last scene of the film is dropped by a crippled blind man. This is the perfect summary of the story, containing all the pessimism the creator infused into his work. The blind man stands on the edge of a precipice. He tries to take a step forward but almost falls. He maintains his balance, but the aforementioned picture of the god falls from his hands. Kurosawa makes two more cuts, gradually moving the camera away from the character, showing his tragic position in a total shot. In doing so, he summarizes the human fate—doomed to failure and estranged from God.

Second Life

Our fate was decided in a previous incarnation, says Lady Kaede to Hidetora, and her words echo the message of Throne of Blood and add another meaning to Ran. The main character repeatedly recalls his life and makes a clear distinction between “then” and “now”. Now he is old, tired, and bitter, but once—he attacked and condemned the innocent to death. Exiled and betrayed by his sons, he roams his kingdom with only the fool remaining with him until the very end. Their journey leads through the ashes and ruins of villages and estates that Hidetora conquered in his “previous” life.

Kurosawa’s vision is dark, but that’s not the end. Evil returns to the person who committed it – this would still be justice, but usually, death befalls the innocent. Just as during the siege of the castle, Hidetora surrendered to death and could not regain it, so in the tragic finale, he is ultimately punished by fate. His youngest son, Saburo – the one he disinherited – turns out to be the most loyal. Despite his father’s decision, his attachment remained unchanged. He takes in the insane, ailing Hidetora and takes him to his castle. In one of the few hopeful scenes, we see them both riding a horse, smiling, happy, eager to talk to each other. The specter of death, previously silent, now manifests as a gunshot from an unknown direction. For a few seconds, it is not clear who the bullet hit—then Saburo slowly slides off the horse and falls dead to the ground. Is this fair? Have you left forever? – cries the father over his body, as if not believing that his son awaits reincarnation and a new life, which is, after all, the basis of Buddhist beliefs. Moments later, he dies of grief. Is this the ultimate end for him too?

Fire and Water

We increasingly distance ourselves from Shakespeare, with less literal adaptation of his text to film, but more universal and timeless meanings. Kurosawa claimed that placing a film’s story in the present makes the work lose relevance over time. Preparations for Ran supposedly took ten years. During pre-production and filming, the director lost many close friends: in 1983, his long-time collaborator Takashi Shimura passed away; during the first days of shooting, sound engineer Fumio Yanoguchi, who had worked with Kurosawa since the beginning of his career, collapsed and died; and finally, Kurosawa’s wife, with whom he had spent 39 years, died while he was working on the film. The seventy-five-year-old artist could not help but sense his own end (although he lived another thirteen years and made three more films), and also… the end of the world. The production assistant was Ishiro Honda, creator of Godzilla, which metaphorically expresses the atomic threat to civilization. Kurosawa’s later work, Dreams, also features a scene of a volcanic eruption that, like in Pompeii, brings an end to the lives of hundreds of people. The director expresses his anxiety in Ran through symbolism, which can be found in the color palette, weather, and characterization.

Shots of a cloudy sky mark the passage of time in individual scenes, but as the action progresses, the clouds grow darker and more turbulent, casting a shadow on the ground where the characters tread. The sky becomes a visual indicator of the world’s state. In one shot, particularly hostile weather draws the attention of all the characters. The soldiers look up, and Hidetora comments, What a terrifying sky. However, the image does not associate the sky with God, as is often the case in Christianity.

In the opening scene, color makes it easy to distinguish and identify Hidetora’s sons, especially since Kurosawa stages almost the entire film in wide shots. The fratricidal war between Taro and Jiro (yellow and red) is, in a sense, hell unleashed on earth, and the red-yellow flame at the castle results from the clash of the two armies fighting senselessly. Finally, the characterization changes Hidetora from an old man to a ghost over time. Kurosawa once again draws from the aesthetics of Noh theater, but this time he is cynical. The masks of old men in traditional theater had a solemn character—in the face of the fact that they are the ones who will meet death and the gods and spirits of the dead the soonest. Hidetora’s makeup and hairstyle, with a characteristic gray, pointed beard, indeed resemble an old man’s mask, but in his case, the connotations of death are exceptionally negative.

Hidetora is accompanied by the fool Kyoami (also present in Shakespeare). He mocks the king, comments on his actions, and despite being part of the events, seems to judge them most coolly and accurately. He utters the film’s most famous quote: Man is born crying. When he has cried enough, he dies. These words frame the story. Kurosawa’s narrative recalls the ending of King Lear. The play does not clearly define who becomes the next king (previous Shakespearean tragedies, despite their tragic nature, usually ended with the crowning of a new ruler). The Japanese filmmaker exaggerates this fact into a great question mark, posed by his film—a question mark about humanity’s future. And this is an essential, timeless, and universal question.