KAGEMUSHA: THE SHADOW WARRIOR. Visually Stunning Gem of a Movie

The Japanese filmmaker’s position in the world of cinema is so strong today that he is often thought of as an icon or a monumental figure on a massive pedestal. Kurosawa is rarely spoken of in human terms. People forget that he was an ordinary man who struggled with many problems throughout his life. On December 22, 1971, Kurosawa declared that he had had enough of fighting with producers and distributors.

Worsening depression and alcohol abuse brought him to the brink, from which he decided to jump. After slitting his wrists and the area around his throat, the director ended up in the hospital. The doctors managed to stop the bleeding. Kurosawa recovered fairly quickly, but he still did not know if he would ever be able to create another film. However, he was saved from oblivion by the Soviet Mosfilm, which offered him the opportunity to adapt Vladimir Arsenyev’s autobiography, Dersu Uzala. Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior

Despite the film’s success at the Oscars in 1976, Kurosawa’s subsequent projects remained uncertain. To ensure financial stability, the Japanese filmmaker even agreed to appear in a series of Suntory whisky commercials, the same brand Bill Murray promoted in Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation. When we note that Francis Ford Coppola, Sofia’s father, appeared alongside him while praising the taste of the alcohol, the story of a depressed actor making ends meet in Tokyo because he received no interesting film offers gains new significance. Regardless of how much the Japanese filmmaker’s story inspired Sofia Coppola to create her most famous film, seeing Kurosawa—a man with a significant alcohol problem—advertising whisky shortly after attempting suicide is a profoundly sad sight. Fortunately, his acquaintance with Coppola, who held his work in high regard, was not in vain. When the first Star Wars film by Lucas took over cinema screens in 1977, people increasingly mentioned The Hidden Fortress, which Lucas cited as one of his main inspirations for writing A New Hope. Though this claim is quite debatable today, at the time it captured the imagination of film enthusiasts and producers. When Lucas and Coppola realized that the creator of The Hidden Fortress, none other than Akira Kurosawa, could not secure funding for his next films, they decided to help the Japanese director. Through their influence in Hollywood, they managed to reach 20th Century Fox. Nearly twenty years after Sanjuro, Kurosawa returned to the world of samurai. The result of his work was Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior.

Although not all critics praised Kurosawa’s new story, the film shared the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival with Bob Fosse’s brilliant musical, All That Jazz. It also made an impact at the Oscars, losing in the Best Foreign Language Film category to Vladimir Menshov’s Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears. Awards, however, are not the most important thing. What matters is that with Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior, Akira Kurosawa gave cinema another masterpiece that confirms his greatness. Watching the film today, more than forty years after its premiere, and reaching its poignant finale, one cannot escape the feeling of encountering something truly monumental.

Identity Drama

The story Kurosawa in Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior tells is based on historical events. To avoid getting too detailed, it is set in the 16th century. Japan is in a state of civil war. Competing clans, led by generals known as shoguns, vie for control of the country. Their rivalry has continued unabated since the second half of the 15th century. The conflict is so fierce that there is no talk of peace negotiations. The war can only end when one of the clans achieves dominance over all of Japan and begins to govern according to its own rules.

One of the most influential leaders is Takeda Shingen. His opponents respect him for his excellent horsemanship and perfect mastery of swordsmanship. Shingen has a huge influence on his soldiers. The army is willing to sacrifice itself in the name of his ideals. When the leader is on the battlefield, their morale is so high that even death does not faze them. Unfortunately, during a night visit to an enemy castle, the general is seriously wounded by a shooter hidden behind the walls. Before dying, he asks his commanders to conceal his death for three years. After Shingen takes his last breath, the titular Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior steps in to take his place. The audience knows him from the film’s prologue. He is a thief caught red-handed, willing to do anything to avoid harsh punishment for his crimes. This petty criminal takes on the burden of convincingly playing the role of the charismatic shogun. He must deceive not only anonymous soldiers but also the deceased leader’s close relatives, particularly Shingen’s grandson.

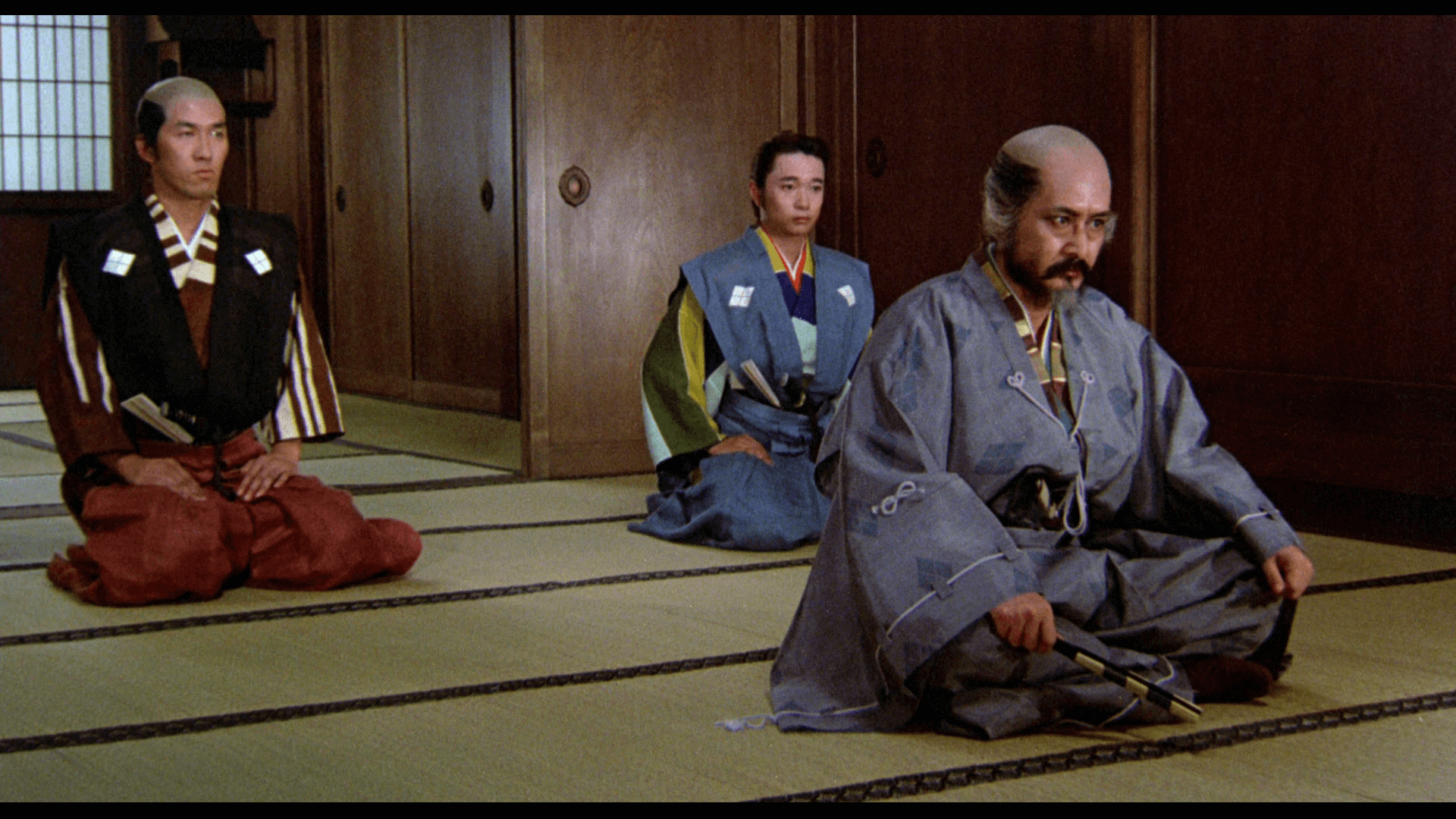

At this point, Kurosawa and Tatsuya Nakadai, the actor playing the role of Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior, begin to create a compelling story about identity. At the start of his journey, the shadow warrior cannot rid himself of the character traits that accompanied him before his capture. One of the first things he does after being left in one of the shogun’s private rooms is attempt to loot a large vase. To his horror, he discovers that the tightly sealed container holds the embalmed body of the deceased leader instead of valuable stones and metals. This encounter with the dead Shingen is one of the most crucial moments in the film. It marks the beginning of the protagonist’s internal transformation, as he gradually starts to lose his own personality in favor of adopting the characteristics of the deceased shogun. The leader’s life, especially his close relationship with his grandson, who loved him unconditionally, begins to draw the protagonist in more and more. The necessity of constantly playing the role leads the shadow warrior to a crisis of identity. At a certain point, unnoticed, the thief abandons his own personality and loses himself in the character he is portraying. The shadow warrior adopts Shingen’s way of speaking, learns to perfectly mimic his movements, forms a strong emotional bond with the grandson, and begins to think according to the ideals of the deceased ruler. The line between the shadow warrior’s identity and Shingen’s blurs increasingly. Therefore, when circumstances force the commanders to expose and denounce the man before the subjects, the thief does not return to his old life. He remains a mere shell of a man—an empty vessel, initially filled with his own identity, and later with Shingen’s. Kurosawa brilliantly illustrates the demonic nature of masks, demonstrating how role-playing can lead to the destruction of identity. This is not about their theatrical dimension but their social one. When a symbolic mask appears on our face too often, the moment when we forget what our true face looks like is only a matter of time.

Samurai Elegy

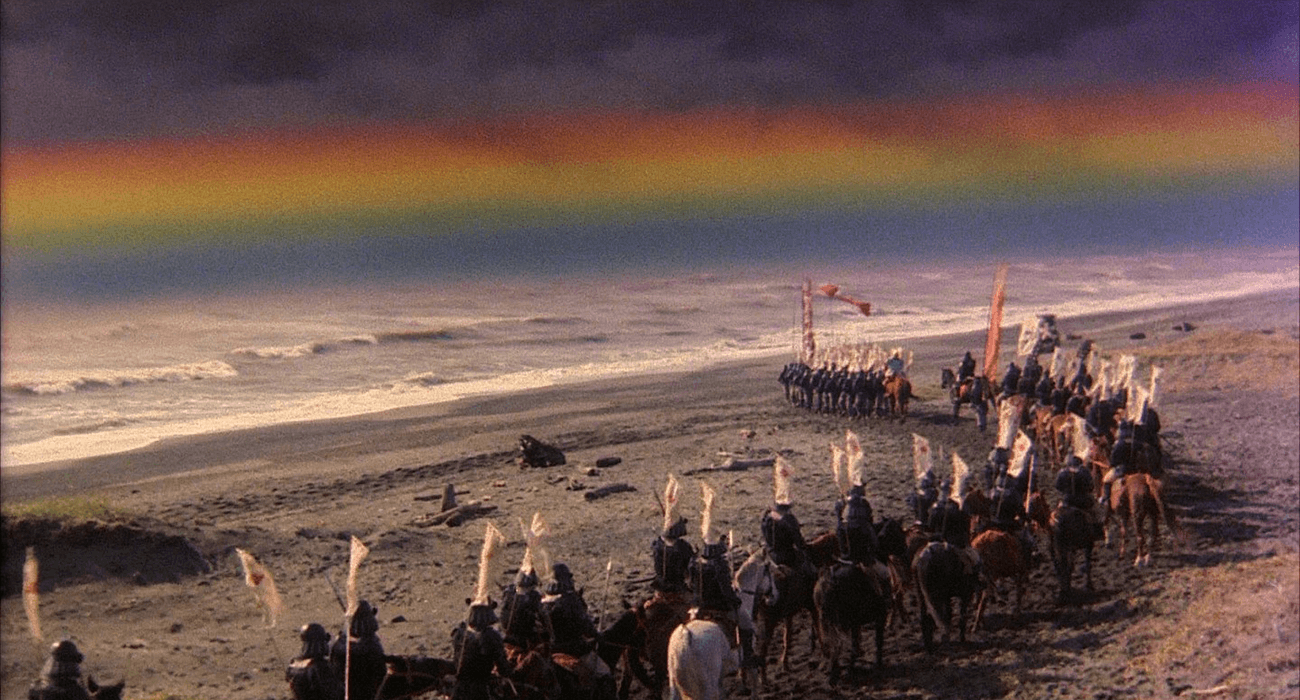

However, Kurosawa would not be himself if he did not place Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior ‘s story in a much broader context. That is why the personal drama translates into the tragedy of the entire Takeda clan in his film. When the protagonist pretending to be the shogun for the commanders’ sake is expelled from the city, the symbolic mask of political intrigue among military leaders is also shattered. Without it, the clan becomes somewhat defenseless, naked, completely exposed. Shingen is dead, we have no leader, and the man you have been bowing to was a thief we picked up from a filthy street. Greatness was built on a lie. It is hard to follow people who make a shogun out of a criminal. Even when the rightful heir, the deceased leader’s son, comes to power, it is already too late. The chance for victory in Japan’s civil war died with Shingen, which is expressed in the poignant battle sequence of Nagashino.

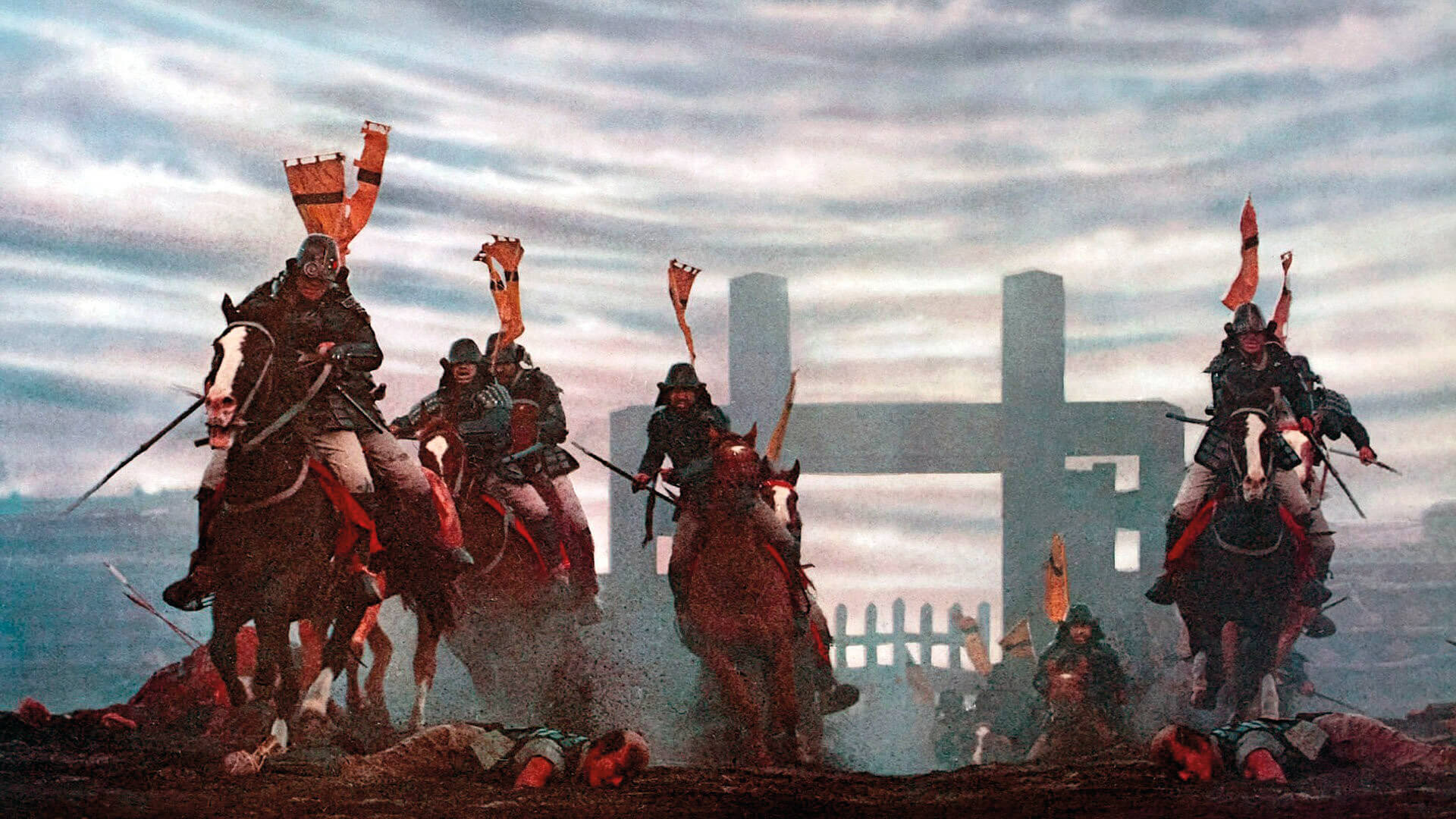

This battle scene of Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior takes us to an even higher level of metaphor. It is hard not to get the impression that as Kurosawa carefully shows the bodies of soldiers and horses falling to the ground, killed by bullets fired by enemies hidden behind a solid palisade, a chapter in history is coming to an end. Swords, spears, and bows give way to firearms. In the smoke of burning gunpowder, old Japan dies. Although history teaches us otherwise, as we know that after the civil war, Japan entered a period of isolationism, and the role of firearms significantly decreased again, the battle sequence of Nagashino leaves little doubt about the director’s intentions.

When the titular character: Kagemusha: The Shadow Warrior, observing the execution of Shingen’s army from hiding, at the end of the film, when it is all over, decides to run onto the battlefield and gallop towards the sinking family banner, we are witnessing a desperate attempt to save the existing state of affairs. Here is a man without identity, an empty shell, racing towards a piece of cloth symbolizing the ideals of the fallen soldiers. On one hand, it is a desperate cry of an individual making one last attempt to fight for his lost identity. On the other, it is a struggle to preserve the memory of a clan that has just ceased to exist. And thirdly, it is a sad reflection on times that—despite often falling victim to creating false mythologies—disappear with the shots of guns. No matter how you look at it, it is a lament. Profoundly sad, yet overwhelming in its beauty.