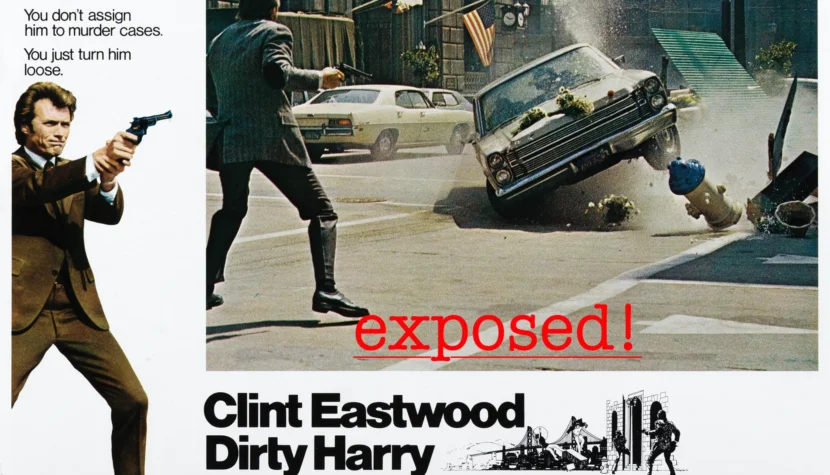

DIRTY HARRY. The One and Only Harry Callahan “Exposed”

Nicknamed Dirty Harry, the protagonist of five films made between 1971 and 1988 is a relentless enforcer of the law, fighting crime with his own methods, often contradictory to the rules.

The movies featuring Dirty Harry are classics of action cinema, whose influence can be seen in many later productions of the genre. Much of this is due to Eastwood’s character, who significantly shaped the archetype of the rebellious, brutal, but just cop, recurring in many films. Though Callahan’s character may seem very simple and consistent, it was a figure intriguingly developed over the years and subsequent films.

Dirty Harry first appeared on screen in 1971 in Don Siegel’s film simply titled Dirty Harry. Despite controversies, the film was a success, allowing Eastwood to reprise his role as Callahan in Magnum Force (1973), The Enforcer (1976), Sudden Impact (1983), and The Dead Pool (1988). Subsequent productions in the series are fundamentally similar and maintain the same convention. The main storyline remains unchanged – Harry Callahan fighting crime on his terms, often battling not just criminals but also bureaucracy and conservative regulations. Opponents changed, times slowly changed, but Harry always remained the same, faithful to his rules and methods of action. However, it is worth noting that individual films differed in details, seemingly insignificant but decisive for the character of each episode, with each film directed by a different director (after Siegel, Ted Post, James Fargo, Eastwood himself, and Buddy Van Horn took turns behind the camera). These subtle nuances significantly influence the development of Harry’s character.

Dirty Harry – the first and best of the series – is a film with the most brutal and dark tone. The plot centers around Callahan’s duel with the psychopathic killer Scorpio, with their entire battle unfolding in the nihilistic, degenerate world of San Francisco at the turn of the ’60s and ’70s. Although the film was read as a glorification of violence and solving problems by force, the matter is more complicated as Dirty Harry does not seem to praise anything but rather paints everything in dark colors. The heavy tone of the original was maintained in Magnum Force and The Enforcer, with both films breaking the oppressive atmosphere with clearer humorous accents, and Callahan stepping back from the central position in the film, becoming more of a key element of the story than its main subject (especially in Magnum Force). Sudden Impact offers a more different story, not only sending the visibly older Callahan from his native San Francisco to the seaside San Paolo but also problematizing the motives and actions of the murderer he is tracking, significantly changing the course of the division between good and evil. The most distinctive part is the cycle-ending The Dead Pool, where Callahan entered a world dominated by media and celebrity pop culture, and the whole story took on a decidedly comedic tone, sometimes bordering on parody.

Like the subtle changes in the films, the main character underwent certain transformations. Dirty Harry was a character generated by the times in which he functioned, serving as a necessary byproduct of the social system. Over time, with changes around him and successive crimes and criminals he encountered, Callahan underwent some psychological evolution. During this time, he had to problematize his unwavering code of law enforcement and reevaluate some elements of his worldview. In such an ostensibly uncomplicated character, developed over seventeen years and five films, we can observe the transformation of “dirty,” brutal force of justice into a still “dirty” but more restrained figure of a hero despite himself, sometimes an inconvenient bastion of law.

The most formative film for Callahan’s character is, of course, Dirty Harry. This film can be treated as an in-depth, crime-tinged characterization of the main character. In the 1971 work, Eastwood establishes the image of the inspector in a tweed jacket, with an angry grimace on his face and a .44 Magnum in hand. This film also clearly shows the genealogy of Callahan’s character – born from the irritating tension between law and justice in a degenerate society. Cynical, cold, and unwavering in his pursuit of eliminating evil, the policeman is, on one hand, reprimanded and unwanted by the legal system, but on the other, he is its ultimate and most effective weapon in the fight for order and safety.

Harry’s identity is defined in opposition to the innocent people-killing Scorpio, whom he must confront. Both are two sides of the same coin, products of a decayed civilization where evil has become mundane and practically the norm. From the rot of society, Scorpio was born, looking like a former hippie psychopath with a twisted peace sign on his belt, methodically killing random victims and playing a perverse game with law enforcement. The bitter remedy for this pathology is another kind of pathology – Dirty Harry, born from the same system. He channels suppressed aggression in response to violence and evil, representing essentially the same violent element as the antagonist, but used in a reversed way and, in a sense, “tamed” for the good of citizens.

Both Scorpio and Harry embody the dark side of society, and their struggle can be seen as an internal, autoimmune battle of the culture itself. The scenery of their three main confrontations is noteworthy: the first two take place at night, under a great (silent) cross and in a deserted stadium, bleak symbols of Western civilization. The third and final confrontation occurs outside the city, in a remote quarry, as if what happens between Harry and Scorpio is meant to be hidden from public view. Each of these scenes has the flavor of something subconscious, unwanted, and repressed from awareness. Viewing Dirty Harry in this way, seeing the policeman and the murderer’s battle as an archetypal conflict, considering the film’s message as glorifying violence is superficial – the film and Harry Callahan’s character do not justify administering justice outside the law but rather show the contradictions and hidden forces within society. Harry is an emanation of social stagnation and the brutal will for justice it generates, acting on the principle of lesser evil. One could say he is indeed a hero of his time, an element unleashed by the progressive decay of society and culture.

Crime and Punishment

It’s not that Dirty Harry is a character devoid of feelings and empathy. Already in the first film, his relationship with partner Chico Gonzalez reveals Callahan’s more human side, valuing loyalty and capable of restrained friendship. These positive feelings, hidden under the mask of a brute, are what ultimately most distinguish Callahan from Scorpio and most strongly tie him to police service, and thus society. Despite his unsympathetic tough-guy image, Harry befriended virtually every partner he worked with, even if it meant overcoming prejudices, as in the case of Kate Moore, his partner in The Enforcer. Callahan’s methodical nature also excluded sharp conflicts with his closest colleagues, so even with the reluctance to an inexperienced woman in this role, in none of the episodes did any tensions between Harry and his partners go beyond verbal jabs, which were part of Callahan’s distancing strategy since his partners often ended up badly (only Al Quan from The Dead Pool survived while remaining in the police). Despite his rebellious individualism, Harry always adapted to what was expected of him and largely accepted the rules imposed on him by his superiors – all in the name of the higher value of protecting the city from evil.

Probably the somewhat hidden sense of loyalty and empathy for victims made Callahan return to the police after the dramatic finale of Dirty Harry instead of administering justice on his own, sinking into an unrestrained cycle of punishment. From Magnum Force, the process of gradually nuancing the inspector’s black-and-white vision of the world began, forcing him to reflect on the boundary between good and evil. In the second film in the series, Harry’s opponents were no longer criminals but a police organization administering justice on their own. It might seem that this solution would suit Callahan’s beliefs, constantly hampered by the system and suffering when his arrests were nullified by legal loopholes. However, in Magnum Force, Dirty Harry, after confronting his collective alter ego, opposes the organization and defines himself as a reluctant defender of the flawed legal system. This gesture is important as it clearly delineates a boundary that previously seemed unclear or nonexistent to him. This stance continues in The Enforcer, where he stands unwaveringly on the side of the justice system while openly despising it.

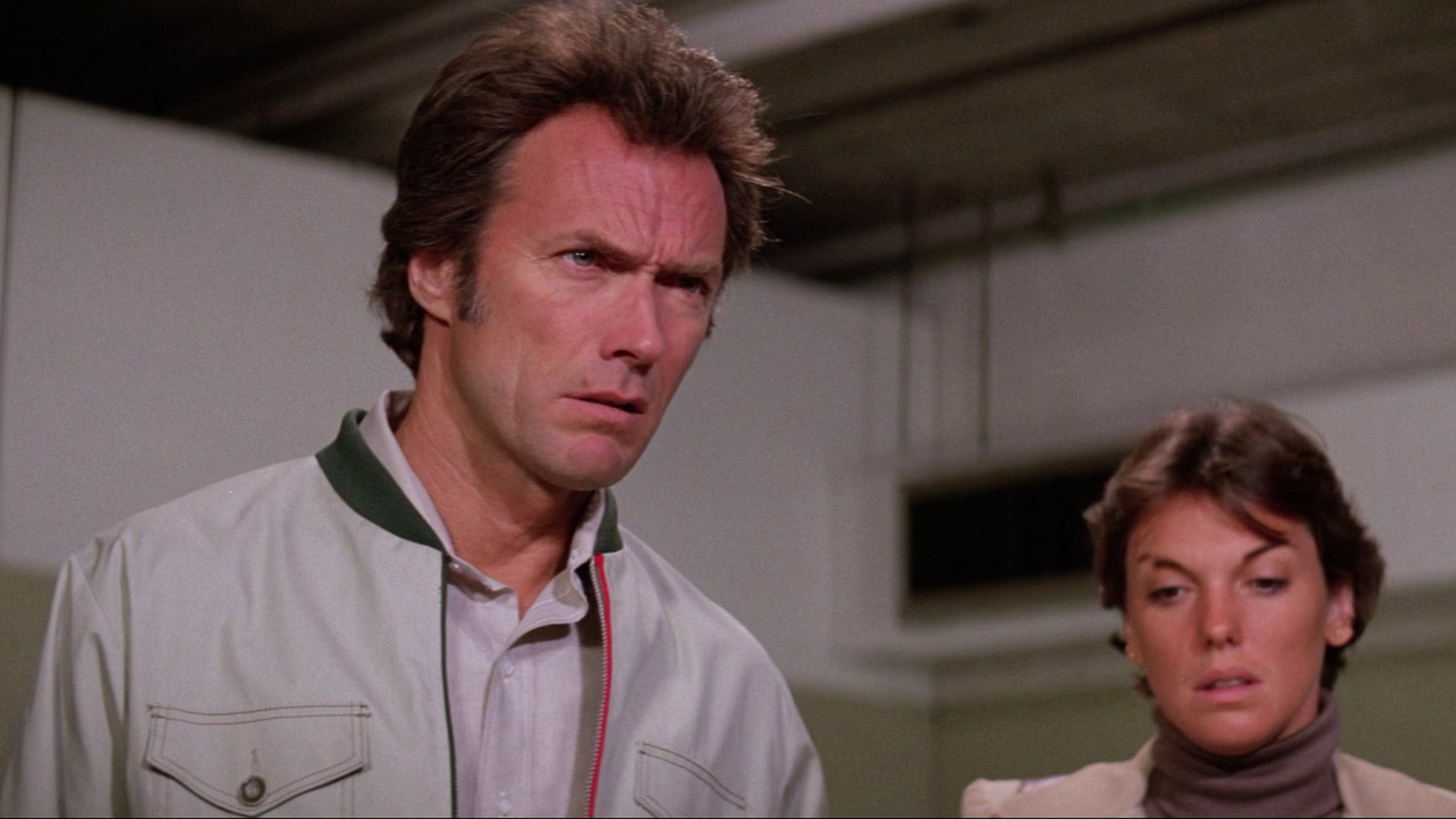

The recognition of the ambiguity in distinguishing between good and evil and the arbitrariness of the division between the forces of law and chaos makes Callahan seem to create himself as a guardian of citizens, who, out of necessity, operates within a decaying system. His disdain for his own camp quickly began to merge with the recognition of ambiguity on the other side of the barricade. In The Enforcer, tracking a terrorist group, Harry collaborates with Big Ed Mustapha’s anti-system organization (clearly referring to the real Black Panthers), which ultimately proves more helpful in fighting evil than the bureaucratic Police Department and prosecution. This theme of nuanced positions of opponents of power structures and Harry’s recognition of not only the good among them but also the motives of opposition is most fully developed in the seven-year-later Sudden Impact.

In the Eastwood-directed film, the main “antagonist” is Jennifer Spencer, an artist grappling with the trauma of gang rape and seeking revenge on the perpetrators who escaped punishment after the case was covered up by the local police. While tracking the murderess, Harry realizes the ambivalence of the killings and unexpectedly begins to understand the motives behind her actions, which stem partly from helplessness in the face of a pathological legal system. The unwavering law enforcer seems to recognize the similarity between his value system and actions and Spencer’s motivations, in a way acknowledging the validity of her vendetta. This confrontation causes a significant shift in Callahan’s character, ultimately dismantling the perception of good and evil in “either-or” terms and leading to a highly problematic understanding of crime and punishment. The inspector’s final choice reflects this inner transformation, the relativization of values and actions through their context. Simultaneously, it represents the development of Dirty Harry’s unwavering belief in standing up for the oppressed, deepening the pessimistic, almost nihilistic vision of reality presented in the series due to the ambiguity of both crime and punishment.

Mythical Hero

Five years after his encounter with Jennifer Spencer, Harry Callahan returns in The Dead Pool, which takes place in a significantly different reality from the previous parts – media play a crucial role, America has become a celebrity culture, and ubiquitous drugs take their toll. In this world, Harry Callahan remains the unchanged factor, still standing guard over law and order with the same methods and attitude. However, at the very beginning of the film, a strange thing happens – instead of being disciplinarily transferred or at least severely reprimanded by his superiors after another spectacular action, Harry becomes a media hero, famed for his role in convicting a notorious gangster. Callahan finally transitions from a rebel to a star and the face of the San Francisco police.

The visibly tired officer surprisingly adapts well to the new world, fitting into the media realm despite a certain reluctance, becoming an icon of justice, with his tough demeanor and methods crystallizing into a kind of heroic image. It can also be seen that his near-celebrity status somewhat satisfies the eternally criticized Callahan, who is already contemplating retirement. Notably, in this film, his classic quotes – the gun-counting ending with the disdainful “Do you feel lucky, punk?” and the provocative “Go ahead, make my day” – are replaced by references such as “You’re out of bullets” (after the villain seizes his Magnum) and the final “You’re shit out of luck,” which seem to close Callahan’s provocative lines. It seems that having achieved the status of a local hero, Dirty Harry is ending his career, highlighted by the fact that the final walk from the scene of the fight takes place this time in the company of a journalist with whom he previously had a romance.

In the last film, we find the least of the classic Dirty Harry atmosphere, which has given way to pop culture and sensational clichés. Both the reality and Harry’s status have changed, as well as the presentation style – crime and violence have become more exaggerated, and the criminals grotesque. For the first time, we also do not know the identity of the murderer from the beginning, making the whole film more of a classic crime story than the existential action drama that the previous parts were. Callahan changes with the times – a character born from the unrest and ambivalence of the ’70s, in the ’80s transforms into a pop culture cliché, with his struggles and dilemmas covered by the veneer of his iconic status. This screen journey seems to correspond with Dirty Harry’s function in popular culture, where from a grim niche, Callahan has moved into the canon of the most recognizable film characters.

The dynamics of Dirty Harry’s character can largely be seen as representative of the transformations in American culture, drifting from the conservatively-tinged disillusionment of the Woodstock generation, through the gradual opening to social, equality, and feminist criticism, to the media-dominated, pop culture reality of the global world. The subsequent episodes develop the character of the hero within this sketchy trajectory, making him an interesting carrier of cultural reflection. Thanks to Clint Eastwood’s restrained acting and consistent control over the series, the character’s transformations are credible, and Callahan over the years remains a coherent figure. His sparse facial expressions, hard certainty, and irony, with which Eastwood endowed Harry, perfectly communicate his simple but internally tense identity as a rebellious hand of justice. Simultaneously, this minimalism in expression convincingly portrays all stages of character development and his transformation from a brutal force in the service of the law to a media personality. Thanks to significant discipline and interesting changes introduced in the subsequent films, Callahan is one of the most important cinema heroes, changing with the times, and the series with him is an excellent example of how action cinema can express the spirit of the times, enriched with new contexts.