8½: Federico Fellini’s Seminal Masterpiece Deciphered

…– and which remained in the works of this screen magician until his death, was dormant within the artist from the very beginning, gradually awakening from this long slumber and subtly revealing itself in his early films, unobtrusive to our attention.

One might assume that, like any debuting creator, Fellini was searching for his style – his unique “stroke,” which he learned and perfected in his early works – realistic and seemingly devoid of poeticism. However, there is another aspect of this situation – Italian neorealism, which had been developing since the end of World War II and constantly influenced the master, in a sense restraining his lyrical inclinations. Nevertheless, Fellini’s entire body of work (despite the radical stylistic change in 8½) is decidedly personal and authorial; and the departure from realism should be attributed more to the internal development of the artist than to a liberation from the prevailing trend, whose decline we observe in the second half of the 1950s. Therefore, we can confidently encompass the works of the La Strada author with a single frame and sign it with his name.

Evidence? In every Fellini film after 8½, which marks a clear division in his filmography, we can see elements of the style whose seeds are found in his early works (speaking of early works, I mean films made before 1963). One such element of Fellini’s authorial idiom is the autobiographical nature of his works. Federico Fellini populates his worlds with characters created based on real people. Their silhouettes lingered in the director’s memory, leaving their mark on his consciousness. An example here is Saraghina, a local prostitute from Rimini, whom the director recalled in Otto e mezzo. However, apart from the recurring motifs in Fellini’s works, such as the fondness for bizarre characters, recurring landscapes (very often the beach), the broadly described phenomenon of vitellonism (emotional and social immaturity), and the significant scenes following “orgiastic” sequences (I Vitelloni, La Dolce Vita), I will return to the issue of poeticism, which I believe is a kind of key to the author’s style of the screen magician.

In my opinion, poetry (or “screen poetry”) is a very vague and unclear concept – something inherently not so much indefinable as extremely resistant to rigid and clumsy words of definition. However, feeling obliged to attempt to outline this term, I will quote Mirosława Salska-Kaca, who in the article Selected Problems of the Style of Poetic Film defines the phenomenon as follows:

[…] The poetic film, instituted by the lyrical function, is generally characterized by the evocative nature of the depicted reality, the metaphorical construction of the narrative, aiming to stimulate the viewer’s associations; particularly important in this statement is the emotive and autotelic function […].

Thus, when dealing with a poetic film, we encounter a certain additional organization of the filmic text. Simply put – a certain depth of meanings. For example: in the final scene of La Dolce Vita, the main character – Marcello (played by Marcello Mastroianni) – is unable to hear the call of a girl standing nearby. She is drowned out by the sea waves. At first glance, the scene is understandable. However, upon closer inspection, we notice elements that hide meanings and demand interpretation. How to recognize such an additional construction of the scene? The first clue is the grotesqueness of the whole situation. The distance between the characters is small. Just a few steps would be enough for the characters to communicate with each other. Instead, Marcello kneels in resignation on the sand while the girl unsuccessfully tries to shout over the noise on the beach. Of course, this brilliant scene should be interpreted in the context of the whole film and all the information we gathered during the screening. Thus, the girl on the beach can be interpreted as a symbol of a certain kind of “purity” that Marcello longs for – as the opposite of the corruption that Rome in the film is teeming with (You know, you look like an angel from Umbrian stained glass windows? – asks the main character in the restaurant scene). One could say that she belongs to the world of ideas, which the protagonist cannot access due to the hedonistic lifestyle he leads.

Much can be written about the symbolism of the sea in Fellini’s works. In many films, it represents a chance for rebirth (as in the ending of La Strada). It is similar in La Dolce Vita. The final scene by the sea gives the hero a last chance for redemption, which he does not take. He remains deaf to the voice of his angel and, as usual with Fellini, the film ends with a lenient conclusion – the girl’s benevolent smile. There are, of course, more subtle examples of poeticism in films before 8½. I could mention, for example, the symbolic characters from La Strada, which Maria Kornatowska writes about:

[…] Without falling into the exaggeration typical of Fellini’s exegetes, one can assume that the three characters of the film represent three fundamental elements of human existence for the director: sensual corporeality, which confines a person within the limits of their biology and material needs (Zampano); the spiritual element, which constitutes the bond between a person and the world and other people, in contrast to the body, it connects rather than divides (Gelsomina); and fantasy and freedom, which is often the domain of art and dreams (The Fool) […].

The episodic structure of the film (e.g., I Vitelloni, La Dolce Vita in early works, 8½, Satyricon, Roma, Amarcord, City of Women, etc. in mature works), which focuses on descriptiveness, diminishing the importance of the story itself, also fosters poeticism. The emotive function, mentioned by Salska-Kaca, is clearly evident here, as the camera’s eye is set on the contemplation of the presented reality, thereby evoking emotions in the viewer.

Federico Fellini before 8½ is an artist torn between realism and fanciful poeticism. In the 1950s, there was no director in Italy who did not succumb to the influences of Neorealism, as Kornatowska writes:

[…] Neorealism, as a sum of certain searches and experiences, completely transformed Italian cinema, and in this sense, every Italian filmmaker had to find himself within its sphere of influence […].

On the one hand, his films before 1963 are realistic; on the other, we find metaphors and a remarkable fascination with the world of ideals and dreams. Indeed, the obsessive desire to escape into the realm of dreams characterizes all the early films of the master. Wanda (Brunella Bovo) from The White Sheik – Fellini’s Madame Bovary – is a newlywed housewife, engrossed in cheap romance novels and dreaming of great, ideal love. The titular loafers from the 1953 film daydream about grand plans of escaping the province. Gelsomina (Giulietta Masina) from La Strada vainly seeks warmth in another person, while Augusto (Broderick Crawford) from Il Bidone, subconsciously or not, longs for redemption. The cheap journalist Marcello from La Dolce Vita wants to break free from the clutches of empty existence, seeking inspiration and a stimulus, but when he finds them, he remains deaf to their call.

However, reality is not kind to Fellini – it pulls the director down to earth along with the crowd of his characters. Wanda will learn that fairy-tale princes do not exist and will return to her husband; the loafers will likely end their days in the province (except for the youngest, Moraldo); and Gelsomina and Augusto will die in loneliness and oblivion.

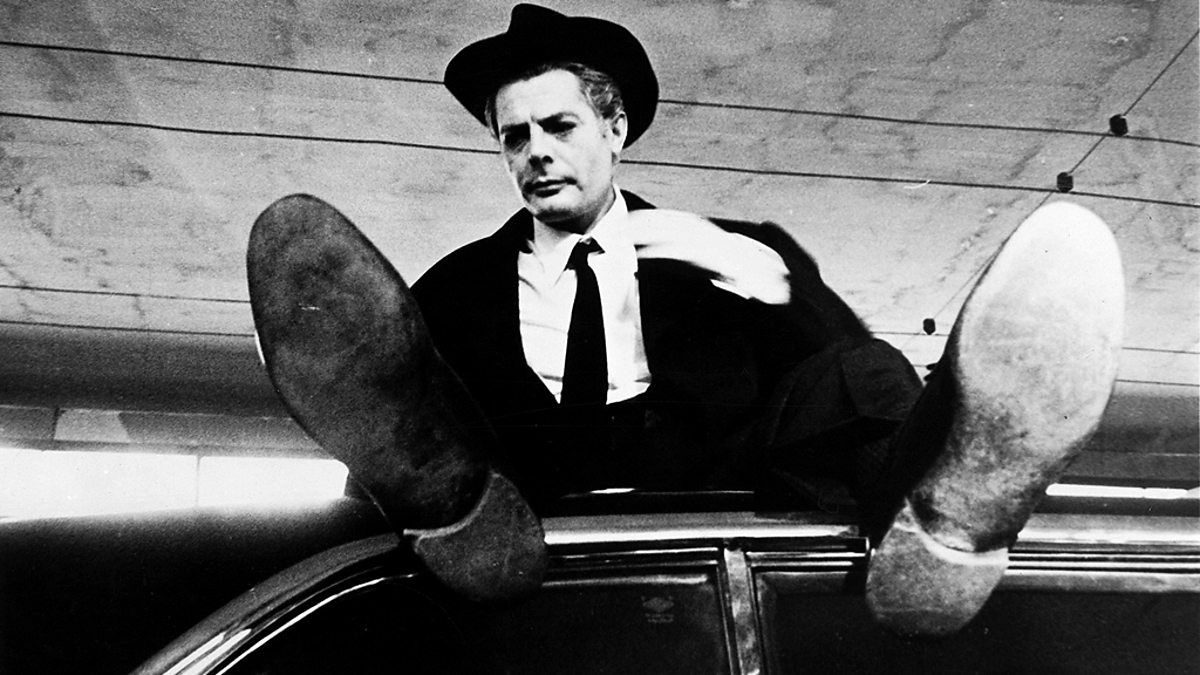

All these works are permeated by the same motif of longing and disappointment – the same one that seemingly haunted the director’s life. Just as his characters long and dream, Fellini longs for the extraordinary and poetry. His thoughts revolve around transcendent ideals, yet something always pulls him down to earth. Whatever it may be: the film environment steeped in the poetics of Neorealism, Italian criticism, or an inner immaturity for radical changes – it gives the impression of some artistic blockage. Therefore, in terms of form, I believe that during this period of his activity, Fellini, consciously or not, compromises with the audience and employs half-measures. Only in 8½ do the poetic tones pour out of the director as if he finally broke the barrier that had weighed him down from the very beginning and gradually subsided film after film. The very first sequence of the main character’s dream – Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) – is a kind of summary of the director’s struggles from previous films. Guido Anselmi is trapped in a traffic jam, suffocating in his car, just as Fellini suffocates in his environment. When he finally manages to get out of the car, he soars into the sky and flies away – free as a bird. However, shortly after, someone (again on the beach!) throws a lasso around his leg and pulls him down to earth. Interestingly, that someone will be one of the journalists appearing in the final scene…

8½ of the Film

The 1960s were an extraordinary period for cinematography. Ingmar Bergman produced a series of masterpieces, the French New Wave emerged, challenging Hollywood’s “cinema of the fathers,” and in Italy, Michelangelo Antonioni presented his famous tetralogy (L’Avventura, La Notte, L’Eclisse, Red Desert). During this time, Federico Fellini broke away from neorealistic mimesis once and for all with the creation of 8½.

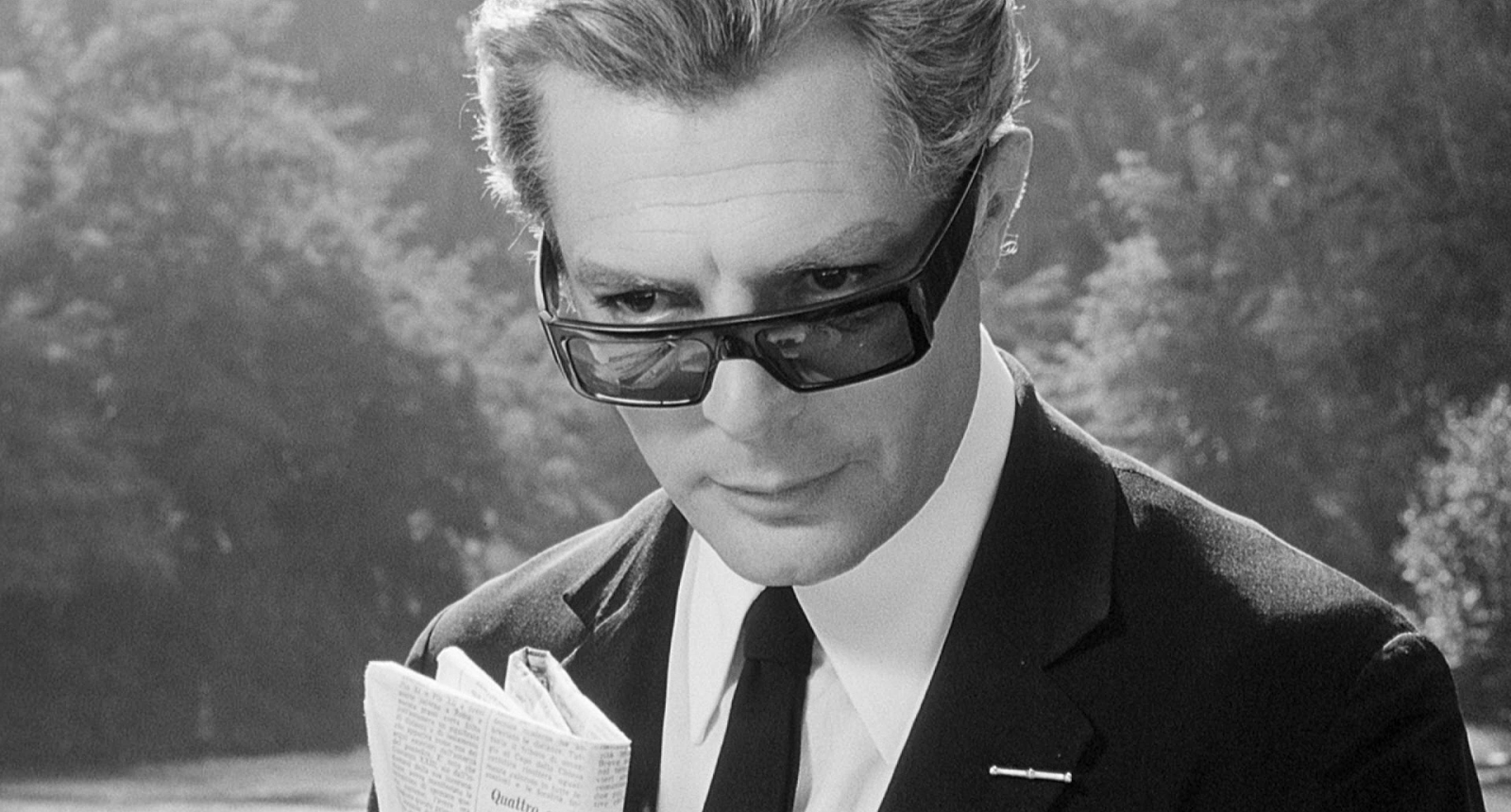

Otto e mezzo is undoubtedly a groundbreaking work, one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of cinema. Why? Primarily because it was unprecedented for its time in its exploration of the protagonist’s psychological state. The film combines a multi-layered structure of meanings with an incredible portrayal of the inner life of the main character. Fellini’s work defies all the storytelling rules established by American screenwriters. The plot here is treated as a pretext for descriptive richness. The director seems interested solely in the psyche of Guido Anselmi—Fellini’s alter ego—which is thoroughly explored in the film.

Guido Anselmi is a director staying at a health resort to recover from exhaustion. His drama lies in the fact that he is in the process of making a new film while experiencing a profound creative crisis:

I assumed that all my thoughts were organized. I wanted to make an honest film, without any lies. I thought I had something very simple to say. A film that could be useful to everyone, that could bury what is dead within us. Instead, I am the only one who lacks the courage to bury anything. There is chaos in my head—this tower I have here. I wonder why things have taken this turn, where I made the mistake? I have nothing to say at all, but I intend to say it nonetheless, complains Guido.

The way Federico Fellini talks about himself in the film is astounding. This is evident even from the title—before 8½, the director had made seven films and contributed two segments to anthologies. Tadeusz Miczka, in his article titled Form and Indeterminacy in Cinema: 8½ as an Open Work, cites an intriguing theory by French film theorist Christian Metz, suggesting that three levels of action can be distinguished in Fellini’s film:

1. The action of Guido’s imagined film (Guido as the hero of his film)

2. The reality in which Anselmi operates (Guido as the hero of Fellini’s film)

3. Fellini’s artistic reality bordering on his real world (Fellini as the hero of his film)