THE TERMINAL MAN: An Unknown Science Fiction Masterpiece Praised by Kubrick and Malick

The Terminal Man is one of the most underrated yet most remarkable science fiction films of all time, which also had some influence on Blade Runner. And yet, almost no one knows about it.

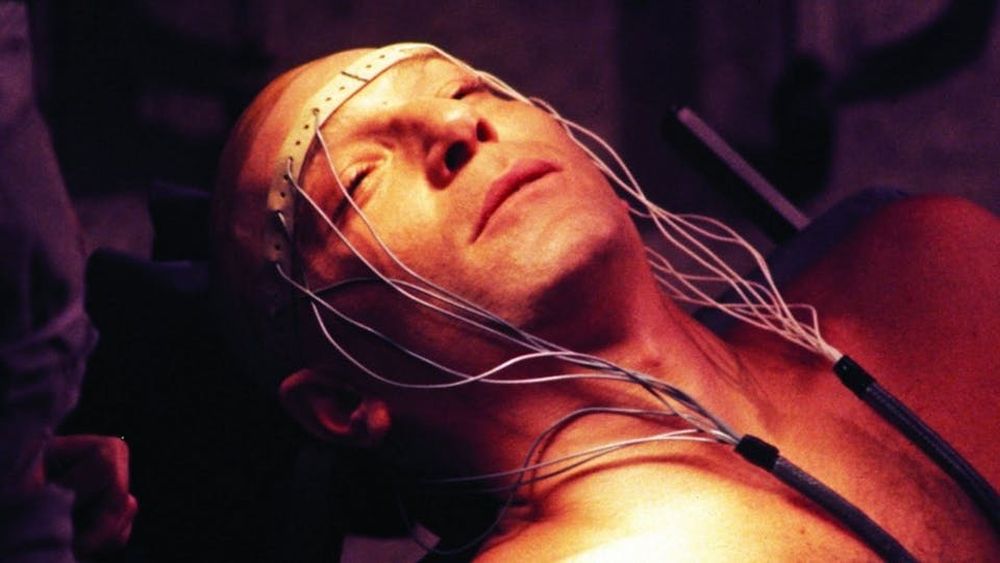

Harry Benson is an exceptionally intelligent computer scientist who believes that one day computers will take over the world. At the same time, he suffers from neurological disorders somewhat reminiscent of epilepsy: during his seizures, he loses awareness but not consciousness, and to make matters worse, he becomes aggressive and uninhibited, with no memory of these events afterward. Benson undergoes an experimental neurosurgical procedure involving the implantation of special electrodes in his brain. These electrodes are designed to detect and neutralize seizures with electrical impulses. The operation is performed by Dr. Ellis, assisted by a team of surgeons and psychiatrist Janet Ross; only Ross and the elderly Dr. Manon harbor doubts about the procedure—both its efficacy and its ethical implications. Initially, the operation seems successful, but a few days later it becomes apparent that Benson’s brain is triggering seizures more frequently, as he has become addicted to the pleasure induced by the stimulation. Worse yet, the dangerous patient escapes from the hospital.

The Terminal Man is an adaptation of Michael Crichton’s 1972 novel of the same name, which was also published in Poland. Crichton, known for works like Jurassic Park and Sphere, saw his book become a bestseller, quickly attracting the attention of Hollywood producers. They were further encouraged by the commercial success of Robert Wise’s The Andromeda Strain (1971), another Crichton adaptation. Warner Bros. acquired the rights to The Terminal Man and enlisted Crichton to write the screenplay, though the studio ultimately rejected his draft. “When I finished, they were outraged. They said I had chopped my own text into pieces. […] I enjoy working on a book and adapting it for film,” Crichton later recalled. The task of writing the script and directing the film was handed to Mike Hodges, the British filmmaker behind the acclaimed Get Carter (1971). Hodges wanted to shoot the movie in black and white but was denied by the studio. Filming took place in Los Angeles during the summer of 1973, with George Segal (Benson), Joan Hackett (Ross), Richard A. Dysart (Ellis), and Donald Moffat (McPherson) in the lead roles.

The film premiered in American theaters in June 1974, but it was a financial flop and received negative reviews. “There is no suspense, and the only frightening moment comes with the fear that the film might last forever. […] The acting is so subdued that one begins to long for a bit of violence,” wrote Nora Sayre in The New York Times. In the UK, The Terminal Man was never distributed, despite a letter of gratitude sent to Hodges by Terrence Malick, who wrote: “You’ve achieved moods I’ve never experienced before in films. […] Your images allow me to understand what an image truly is—not just a pretty picture, but something that should pierce us like an arrow and speak its own language.” Stanley Kubrick was also a great admirer of Hodges’s film (“It’s magnificent,” he reportedly told his collaborator Mike Kaplan), but even he couldn’t convince Warner Bros. to release the film in the UK. It was finally shown there in 2003 at the Edinburgh Film Festival.

It’s easy to see what captivated Kubrick about Hodges’s film, as it shares a style similar to the works of the Barry Lyndon (1975) director. There is the same coldness, aloofness, minimalism, and detachment bordering on neutrality, as well as an absence of emotional exaggeration and overt moralizing, replaced instead by dry, restrained, and matter-of-fact observations. The similarities go beyond style and extend to substance. Like Kubrick, Hodges is merciless in his portrayal of power and authority. While the police in The Terminal Man are little more than comic book-reading fools incapable of keeping track of Benson, the scientists are portrayed as deceitful, vain, and suffering from a God complex. They see themselves as innovators and benefactors seeking to advance humanity through technology at all costs, yet they disregard the ethical implications of their goals. Benson, in their eyes (and hands), is merely a pawn, a means to an end, collateral damage—but not even a victim.

The uncompromising study of violence—both personal, everyday violence and systemic, institutional violence—cannot end happily. The authorities’ response to the violence they themselves created and fueled is even more violence: Benson’s termination. However, he is merely “patient zero,” the first of many. That is why the film’s final scene features the return of the impersonal, all-seeing eye of an unnamed scientist peering into an isolation chamber and saying, “You’ll be next,” as if addressing the audience directly. It’s impossible to overlook that both Crichton’s novel and Hodges’s film serve as a warning against blind faith in authority and scientific progress—especially when that progress ignores ethical considerations. Today, The Terminal Man feels chillingly prophetic. It’s not just that in 2023, doctors implanted a neurostimulator in a patient to control epileptic seizures; it’s that the surveillance depicted in the film has already become a reality. So far, it targets only information, not thoughts or behaviors. For now.

All of this is presented in a stunningly crafted form, with a hypnotic rhythm that captivates from start to finish. The Terminal Man is a slow, deliberate film, designed for patient viewers who don’t struggle with concentration (the surgery scene alone lasts nearly half an hour!). At the same time, it’s a work that should be shown in film schools as an example of flawless craftsmanship. Everything about it is impressive: the composition of shots, camera movements, storytelling, the script’s subtleties and layered dialogue, the understated yet meaningful symbolism, and the restrained use of music (Bach’s Goldberg Variations performed by Glenn Gould). Long after the credits roll, images linger in the mind: blood flowing into floor grooves, a view of a room through half-closed blinds, Benson against the backdrop of a stained-glass window, a rose crushed in a hand during a fit of rage. Don’t be misled by the few low ratings on popular film sites: The Terminal Man is a true masterpiece of science fiction.

P.S. A trivia tidbit for film enthusiasts: The Terminal Man undoubtedly influenced Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) on several levels. The tunnel where Benson waits for Angela is the same tunnel Deckard travels through. The grim reception scene in The Terminal Man takes place in the Ennis House in Los Angeles, which not only appears in Scott’s film but whose concrete blocks were also used to build sets (such as Deckard’s apartment interior). During production, Hodges was inspired by the paintings of Edward Hopper, particularly for their depiction of “the loneliness of urban America” [2]. Hopper’s Nighthawks was one of the artworks Scott showed his crew on the set of Blade Runner.