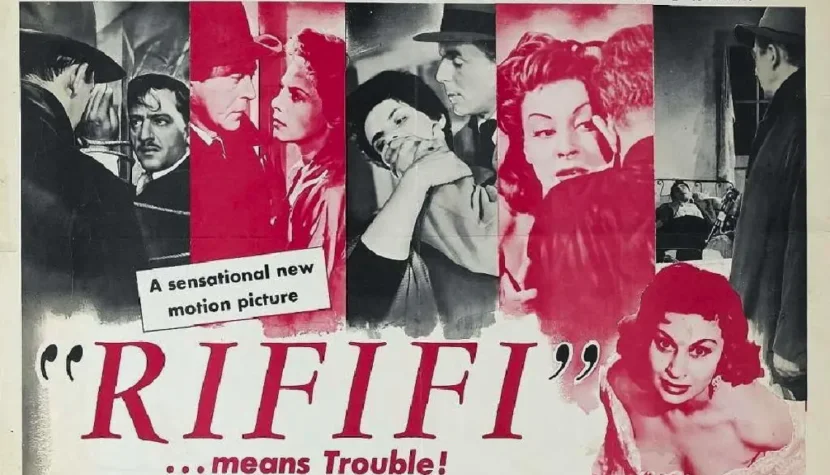

RIFIFI: A Stunning Heist Movie Masterpiece

Du rififi chez les hommes—the full original title—is as catchy and mysterious as it is somewhat amusing. And untranslatable. Czechoslovaks came close, boldly titling Jules Dassin’s work A Fight Among Men. Too literal, though, and far too superficial. In reality, the phrase is a slang term that originated during World War I, combining elements from three different languages. It refers to a tense and often chaotic situation, typically culminating in a violent confrontation among its participants—implicitly those from the underworld. This definition far better reflects the character and oppressive atmosphere of the adaptation of Auguste Le Breton’s novel.

This 1955 precursor to the heist film subgenre—Kubrick’s The Killing, which has a similar premise, debuted exactly one year later, although Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle technically came first—earned its place in cinematic history largely because of its burglary sequence. Nearly 30 minutes long, the heist is executed with meticulous precision and unfolds in near-absolute silence, devoid of music or dialogue. Even today, it makes a stunning impression, keeping viewers on the edge of their seats with heightened blood pressure, growing curiosity, and held breath. However, this sequence is merely the cherry on top of the true crème de la crème of a genre that, by the mid-1950s, was beginning to fade but was far from uttering its last word.

This genre was largely an American domain—and so it is here. Despite his French-sounding surname, Dassin—a Russian Jew by descent—was born in Connecticut and had long been contributing to Hollywood’s “noir” productions. He was responsible for classics like Brute Force and The Naked City. However, when the Communist witch hunts began in the United States, he was accused and forced to flee, leaving a lasting mark on his life. He later returned to the U.S., although he permanently settled in Greece, where he passed away in 2008. During his exile, he directed films such as Topkapi in the following decade. In the meantime, after a period of unemployment during which several of his projects failed, he seized the opportunity to collaborate with the French and outwit his American critics. This is how Rififi was born—a masterpiece in its class that combines distinctly American elements with a thoroughly European approach.

From a contemporary perspective, the story is as old as time itself. A world-weary, hardened ex-convict and expert burglar is released from prison after serving several years. Jaded and betrayed by a former lover but far from broken in spirit, he wants to avoid returning to his old criminal ways. Circumstances, however, force him to accept an offer to rob a jewelry store, a job that promises a hefty payday. Along the way, it becomes clear that the heist won’t be an easy score, and its consequences will be deadly serious.

It may seem like nothing groundbreaking, yet shortly after the film’s release, François Truffaut—at the time still primarily a journalist for Les Cahiers du Cinéma and not yet a key figure of the French New Wave—wrote that one of the worst crime novels he had ever read had been transformed into one of the best films he had ever seen. There’s something to that, although the formulas and archetypes the film established have since dulled its freshness. Still, it remains a compelling watch, thanks largely to Dassin’s persistence, which led him to significantly deviate from the novel.

In the book, the famous heist was merely a minor detail, whereas in the film, it becomes the central spectacle. Everything starts with it, and it leads to an incredibly gripping finale, perhaps even more thrilling than the heist itself. Forced to play one of the characters—the Italian César—Dassin infused the story with his personal experiences. César shares the director’s interest in women, and his sudden demise, filled with regret, shame, and disappointment, reflects Dassin’s own feelings about being blacklisted. The sense of betrayal that haunted him for the rest of his life is a recurring theme in the film. From the outset, the main character, Tony le Stéphanois—brilliantly portrayed by Jean Servais—punishes his ex-girlfriend for betraying him. Later, César faces a similar reckoning, and ultimately, everyone must confront the relentless force of betrayal, which spares no one, not even the innocent.

One of the film’s strengths is its nuanced morality. There are no simple divides between good and bad. There are no policemen and thieves, no heroes and villains. Everyone has a skeleton in their closet or is engaging in dirty dealings. From the beginning, Tony struggles; he starts by getting into debt during a poker game in a seedy den full of shady characters. He calls on his best friend, Jo, for help, unknowingly sealing both their fates. Tony, Jo, César, and supporting characters like Charlie, Fredo, and Mario—it’s all straight out of American noir, with equally high-quality execution.

So where does the European essence lie? Primarily in… family. Jo, his wife, and their son are Tony’s only true source of happiness. Mario, the mastermind behind the heist, also has a successful relationship. Such relationships are rare in noir films, where characters are usually lone wolves navigating treacherous packs of their own kind. This choice aligns audience sympathy with the protagonists, provokes emotions, and heightens tension. Especially since the gang’s actions inevitably and bloodily impact their loved ones—the only truly innocent people in the story. And in the end, it’s family, not money, that emerges as the central concern. It’s for their families that Tony and his crew are willing to risk their lives. This dual focus makes them authentic heroes and relatable individuals, earning the audience’s support.

The old-world charm is also evident in the intimate scale of the production. Everything feels confined to a small “family,” not just within the underworld but within a microcosm of it. Guns make an appearance and are used frequently, but there are no elaborate shootouts. No explosions, no chases, no grandeur. Even the final, masterful chase through the city relies more on the cinematography of Philippe Agostini and clever editing than on epic tire-screeching scenes à la Bullitt. Add to that a modest budget, an unknown cast (including a young Robert Hossein, a future director, who steals a few scenes as the drug-addicted Rémi), and perpetually overcast Paris skies instead of sunlit California, and voilà! A perfect fusion of two faces of cinema.

Of course, the film isn’t without flaws, most notably in its depiction of women. There are no heroines from American noir, no femme fatales in the pure sense, as the men create their own problems without much help from the women (despite the fact that César’s downfall stems from romantic entanglement). Worse still, the female characters pale in comparison to their male counterparts. In contrast to puritanical America, the film offers glimpses of nudity, but at the expense of giving women meaningful character or, in some cases, a voice.

Although Jo’s wife points out his life mistakes in a moment of desperation, her solitary scene is an exception in a sea of mediocrity. Ultimately, the most one can say about the women in this film is that they exist. And suffer. And sing—the shoehorned musical number explaining the film’s title is the only truly misguided and awkwardly executed element, a misstep Dassin admitted to years later. But it can be forgiven, considering the miracle of the film’s creation and its release in its final form.

Financial constraints forced the filmmakers into compromises and often created a tense atmosphere, which Dassin’s behavior didn’t help. He infuriated producers by waiting for bad weather that stubbornly didn’t arrive for days. He also clashed with the composer, Georges Auric, who had written an overly bombastic score for all the scenes, including the heist sequence. Auric was so proud of his work that he was stunned when told the heist would play out in silence, effectively discarding part of his music. Only after seeing the finished film did Auric concede Dassin was right.

However, the most controversial aspect of the story—revolutionary for its time—remained unresolved. The meticulous depiction of the criminals’ preparations, behaviors, and methods, down to the smallest details, sparked debates. The concern wasn’t just how audiences would perceive this quasi-glorification of thievery but also the potential misuse of this “how-to guide” by real-life criminals. Dassin held firm, and within a week of the film’s release, reports began surfacing about a rise in heists eerily similar to the one depicted on screen. In Mexico, the film was even pulled from theaters. This wasn’t just movie magic—it was the true power of storytelling!