DIABOLIQUE. Thought-provoking Masterpiece of a Thriller

… Henri-Georges Clouzot’s black-and-white film certainly evokes a spectre. Diabolique, the horror production, based on the novel by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, is originally titled Les Diaboliques, which can be literally translated as “She-Devils” (as the film was titled on American television)—especially considering that the main protagonists are two provincial women from the teaching profession, united against a source of all evil: a man. However, the film is not a critical take on the education system nor a judgment on the war between the sexes. It’s a classic crime story, one that also leaves room for punishment. Demons, therefore—the specters of the past, overzealous imagination, and fears within us—deny us sleep, especially when our conscience is burdened with more than just an unpaid phone bill.

Born in the early 20th century in Niort, France—where part of the movie’s action also takes place—Clouzot gained fame in French cinema primarily as a talented editor and screenwriter. He had to wait nearly a decade for his directorial debut, but it was The Wages of Fear, also based on a novel by his compatriot Georges Arnaud, that brought him recognition. Two years later, often compared to and even openly rivaling Alfred Hitchcock for the title of the “master of suspense,” Clouzot (not to be confused with Clouseau!) beat his British nemesis by mere hours in acquiring the rights to adapt Les Diaboliques. Both films were remade years later by Americans.

While William Friedkin’s remake, intriguingly titled Sorcerer and dedicated to the French filmmaker, turned out to be a high-caliber reinterpretation that could rival and, in some respects, surpass the original, the 1995 Diabolique by Jeremiah S. Chechik (the same director who gave the world the holiday antics of the Griswolds), starring Sharon Stone, Isabelle Adjani, Chazz Palminteri, and Kathy Bates, utterly reduced the original to typical Hollywood pulp, robbing it of its greatest strength—imagination.

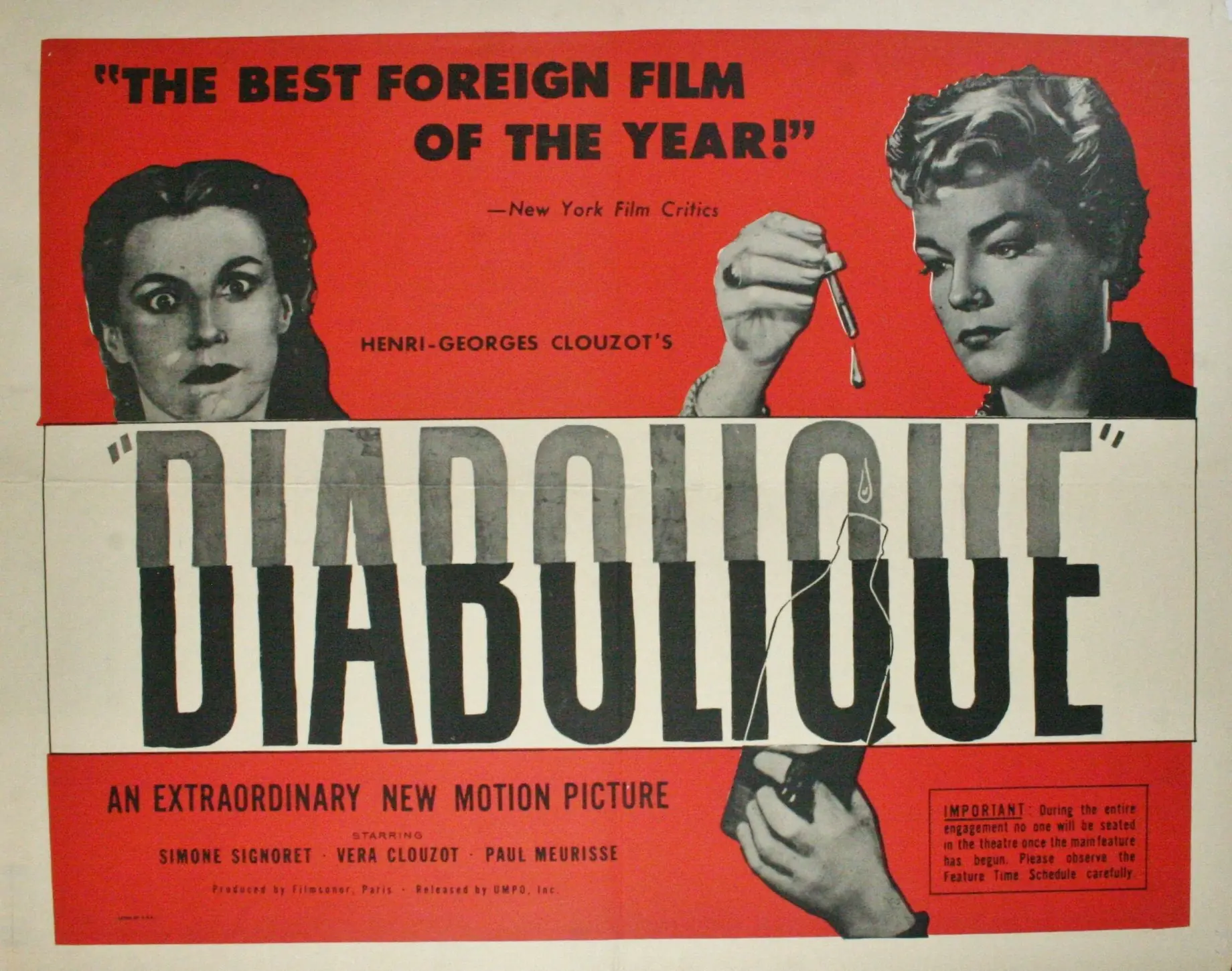

The original Les Diaboliques was aptly advertised as a thought-provoking, even shocking masterpiece that one shouldn’t discuss too much in company—and revealing its ending would be nothing short of a sin (as emphasized by the closing credits). Indeed, even today, it manages to surprise, not with an over-the-top twist à la M. Night Shyamalan, but with a tension built on subtle ambiguities that grip viewers long before the final Fin appears on the screen. In fact, the story engrosses you so thoroughly that you hardly notice its end.

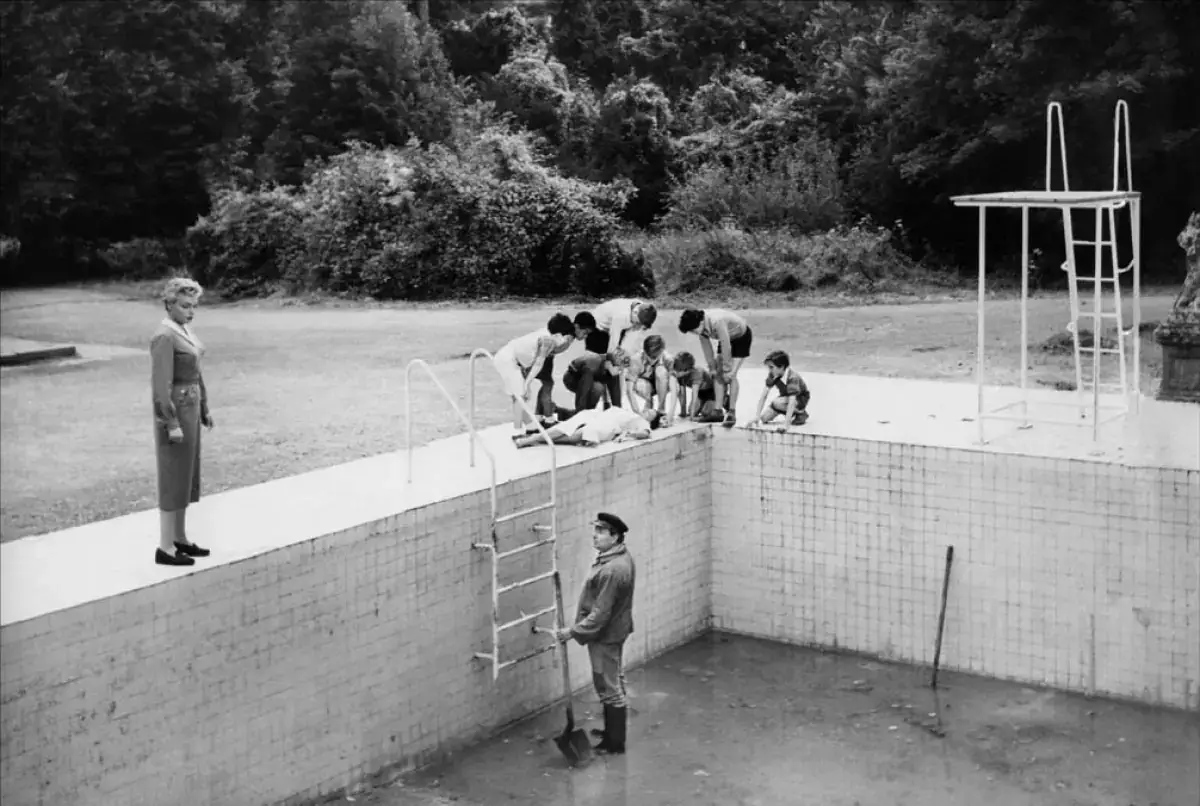

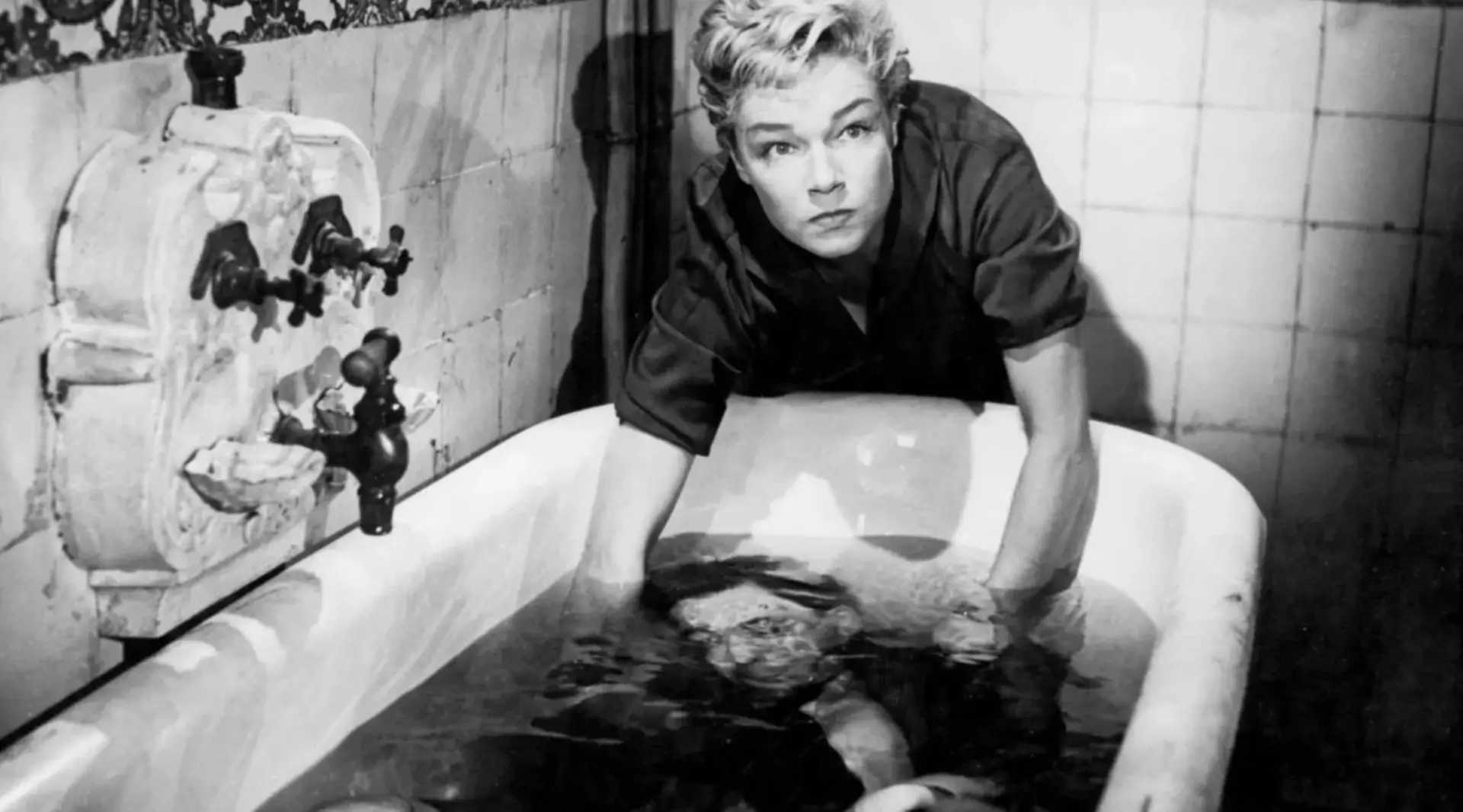

The plot boils down to a simple and beloved cinematic trope—murder. Set in a boarding school ruled by the tyrannical headmaster Michel, the institution is owned by his frail, shy, seemingly innocent wife, Christina (played superbly by Vera Clouzot, the director’s real-life wife, who tragically died of a heart attack a few years later, adding an eerie undertone to the film). Michel emotionally torments her as much as he does the students while carrying on an affair with another teacher, the blonde Nicole (also excellent, reminiscent of a proto-Ellen Ripley, Simone Signoret). Ironically, the two women share a friendly bond, fueled by Michel’s increasingly intolerable behavior. Together, they devise a seemingly foolproof plan to rid themselves of him while preserving their freedom. But loyalty is a relative thing, and the central event is merely the tip of an iceberg bristling with sharp edges. So, just another thriller?

The devil, as they say, is in the details. And these details stand the test of time, even almost seventy years after the film’s premiere, making it extraordinary. I first saw this work just a few years ago, as a mature viewer already familiar with the mysteries of The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, The Shawshank Redemption, or The Sixth Sense, and it made a profound impression on me. It managed to intrigue, lull my defenses, and leave me questioning.

The film’s atmosphere is not particularly sophisticated, yet it’s exceptionally dense. Technically devoid of mind-blowing tricks and shot in a straightforward manner, it nonetheless captivates, making it hard to look away. The filmmakers seemingly reveal everything to the audience—there’s no need to puzzle over or infer subtle artistic nuances—and yet the viewer ends up knowing nothing and doubting everything. It’s a clever approach, as the script is tight, natural, and grounded in reality, while being as captivating as an alien invasion of the White House.

Speaking of American cinema, Hitchcock is the natural comparison here; he directed Psycho partly to outdo the success of Les Diaboliques, which he greatly admired.

Incidentally, the authors of the original novel later wrote another thriller specifically for him—D’Entre les Morts, better known as Vertigo. Comparing the styles and approaches of the two directors, one must credit Clouzot with taking a deadly serious approach compared to his English counterpart. Hitchcock, even in his most serious films, often includes moments of levity or outright humor, and his characters tend to elicit sympathy rather than embody monstrosity in human form.

Clouzot, on the other hand, maintains a poker face, even in moments of respite. As a perpetual cynic, he keeps his characters tightly constrained. These characters, in turn, rarely hold back, often representing the darker sides of human nature and moral decay. Les Diaboliques epitomizes this approach, with its depiction of murder as a disturbingly deliberate choice of the worst possible course of action. Even the children populating the school corridors are no angels. The film is rich in nuance and ambiguity, brushing against the supernatural—a delicate balance easily ruined (as demonstrated by Chechik’s remake).

What we get instead is an exceptionally cold yet emotionally charged film that eschews compromise. Its stark realism—though not devoid of a veneer of theatricality—is amplified by the near-complete absence of a musical score and the outstanding supporting performance of Charles Vanel as the police inspector. His meticulousness, affable persistence, slightly disheveled appearance, and slow-paced demeanor, complete with an ever-present cigar, foreshadow the character of Columbo.

Moreover, the decision to omit the lesbian subplot emphasized in the book enhances the ambiguity of the relationships. The authenticity and chemistry between characters were likely aided by on-set tensions. Prolonged shooting and, according to rumors, the director’s radical approach toward the actresses resulted in numerous conflicts, reportedly mirroring the strained dynamics seen in the fictional story.

Though Les Diaboliques didn’t win any major awards or widespread acclaim among its peers—François Truffaut and Jacques Rivette criticized Clouzot for cheap sensationalism and commercialism (to which he responded by calling the New Wave insular and dull)—it has secured its place in cinematic history. Its box office success facilitated its release in the United States, though a few minutes were cut from the film there. Despite this, it left a lasting impression on Western filmmakers, inspiring Brian De Palma, David Mamet, Stanley Kubrick, and his The Shining.

Notably, the film’s premise was so well-received that it spawned several adaptations, including John Badham’s 1974 Reflections of Murder and Mimi Leder’s 1993 House of Secrets. Even earlier, in the 1960s, Games with James Caan borrowed elements of the plot, complete with Simone Signoret as a sort of femme fatale.

Despite its imitators, the original, featuring Johnny Hallyday’s acting debut and the final performance of veteran Jean Témerson, quickly built a reputation as one of the finest examples of French cinema exploring moral anxieties. Over time, it achieved undisputed classic status, landing a spot in IMDb’s Top 250 and being included in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. That last recommendation is especially apt—Les Diaboliques is best watched alone on a long, sultry evening in an isolated country house.