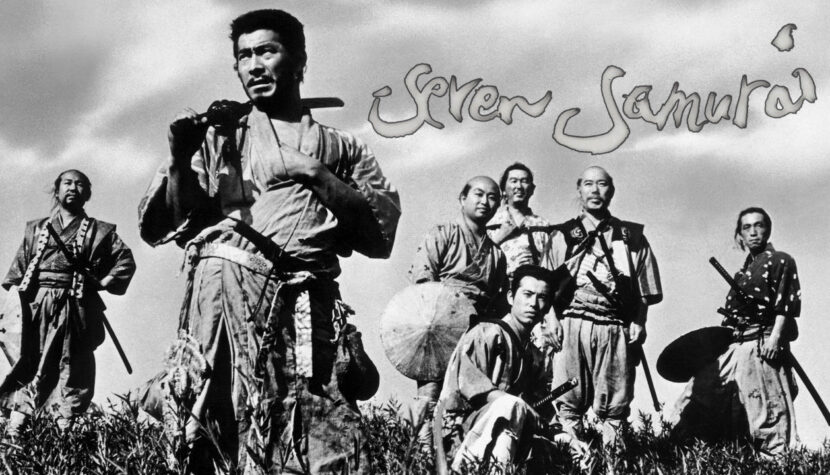

SEVEN SAMURAI. Akira Kurosawa’s Timeless Masterpiece

Every sentence can sound like a truism. I’ll try not to overuse the word masterpiece, as it no longer means anything significant.

In the case of Akira Kurosawa‘s Seven Samurai, such a term is an insufficient argument, too banal for this type of cinema. Although the main factor in the plot is simplicity, the arsenal of techniques used is complex. Diverse character behaviors, dynamic camerawork, rhythmic editing, and a harmonious sound stream – all these influence the viewer’s emotions and have caused the film to consistently captivate audiences of all ages and from all around the world for years.

Few are ready to fight; most hope that others will fight for them.

Sun Tzu – The Art of War

It takes seven well-trained warriors to repel an attack by forty bandits. But creating a simple yet truly epic and universal story requires a much larger team. However, it all started with a brilliantly simple idea developed by three talented writers: Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto, and Hideo Oguni. Taking inspiration from American westerns, they created a world consisting of three groups. The first group is the defenders of law and order – gunslingers replaced by ronin. The second group consists of dishonorable bandits. The third group is the community that the first group must protect from the second. The Japanese authors breathed new life into this rigid formula. The result is a dynamic picture that, despite its rough texture and monochromatic frames, continues to inspire and delight successive generations of viewers.

The American westerns also inspired the characteristics of the main hero. Even if he has a questionable past, he ultimately dedicates his time and skills for the good of the endangered community. Unlike those he protects, he is lonely – without a family and with little to lose beyond his life. He is distinguished by honor, independence, and exceptional strength of character. This collective hero of Kurosawa’s film comprises seven men who feel at home in the heat of battle.

For a film whose plot can be summarized in one sentence, its length is surprising. Two hundred minutes – that’s exactly the time needed to fully immerse oneself in it. Hitchcock might have said it’s a duration exceeding human bladder endurance. But Seven Samurai is watched in one breath, without a moment of boredom, not expecting commercial breaks but absorbing each scene, engaging one’s sight, hearing, and intellect. We witness an adventure where drama blends with humor, tears with laughter, the clamor of battle with the quiet anticipation of the inevitable.

A samurai should adopt the principle of showing no weakness in any situation. Even in small matters, the deepest secrets of the human heart are revealed.

Tsunetomo Yamamoto – Hagakure

It’s worth noting how the villagers are presented in Seven Samurai. They are not unequivocally good people, nor are they the victims they pretend to be. In a group, their animal nature emerges – with bamboo pikes, they can kill a man to rob him. They can kill a lone samurai if they have the advantage and realize they can benefit from it. Due to several characteristics, such as insolence or the ability to steal and murder, they resemble bandits and thus evoke the samurais’ contempt, for whom life is about following certain rules. Hence, the question arises: is it worth risking one’s life for such people? Is it worth sacrificing, knowing that besides satisfaction and a bowl of rice, you get nothing in return? The answer is simple: for a samurai, material goods don’t matter, as wealth is an obstacle to wisdom. Compassion also influences these warriors’ attitudes because, as Tsunetomo Yamamoto wrote in Hagakure, A samurai with only courage, without compassion, will surely perish.

What distinguishes Seven Samurai from Hollywood westerns is the omnipresent nervousness. In contrast, High Noon (1952), a classic of its genre, lacks violence, with tension building very slowly and calmly. In Kurosawa’s film, the mounting tension before the big battle is depicted without such subtleties. Movement dominates, emotions are hard to control. The characters’ faces show true despair and anger, even total, unrestrained fury. The director allows his actors to scream and make all sorts of faces. Toshirô Mifune, in the role of the nameless man (when asked his name, he replies, I forgot. You can give me one), excels at this. His unusual expression of inner turmoil suggests he is not a true samurai. Because according to the samurai code, one should strive for spiritual harmony. Kikuchiyo (the name he eventually adopts) is restless because he grew up in a poor village among weak people who knew no honor. His inner self is torn between contempt and compassion. He carries the burden of his origins on one shoulder and the burden of joining the samurai, whom he wants to impress, on the other.

Both Toshirô Mifune and Takashi Shimura, playing the leader, two of Kurosawa’s favorite actors, were nominated for the BAFTA award in the Best Foreign Actor category. In 1954, the film won the Silver Lion in Venice, but the Oscar went to another Japanese film – Samurai (Miyamoto Musashi, 1954) by Hiroshi Inagaki. It is the first part of a trilogy in which Toshirô Mifune similarly portrayed the legendary swordsman Musashi Miyamoto with brio. When the Foreign Language Film category was introduced at the Oscars in 1957, The Burmese Harp (1956) by Ichikawa was nominated, but Seven Samurai was also recognized with nominations for Art Direction (Takashi Matsuyama) and Costume Design (Kôhei Ezaki).

One can live when it is right to live and die when it is right to die.

old Japanese proverb

Seven Samurai gained even more popularity thanks to a western remake (The Magnificent Seven, 1960), done by William Roberts (screenplay) and John Sturges (direction), who set the action in the Mexican-American 19th century, expanded the character of the villain, and cast the bald Yul Brynner as the leader, inspired perhaps by a scene in which Takashi Shimura shaves his head to impersonate a Buddhist monk (though the baldness had no significance in the remake, and Yul Brynner might not have even taken off his hat). Most importantly, the story told in the western format wasn’t simplified but rather strengthened the original’s message, emphasizing its universality and timelessness.

Kurosawa, Hashimoto, and Oguni told this bitter story without overusing pathos. They introduced a character who, through his clumsiness, provides humor. The funniest scene involving him is probably the one where he tests the maxim Under the best rider, the worst horse will run like the wind. However, this character, played by Toshirô Mifune, turns out to be a tragic hero. The authors seem to say that the one we laugh at may deserve as much compassion as those who appear to be paupers and weaklings.

Who understands human nature, his orders will be carried out as effortlessly as water flowing from the mountains.

Sun Tzu – The Art of War

Technique is secondary, said Kurosawa, but for a director with a recognizable style, it’s hard to overlook when discussing his works. The montage technique known as the wipe, which the Rashomon creator uses as regularly as commas in a review, stands out. The technical masterpiece is the final scene in the mud and rain. In David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson’s textbook Film Art: An Introduction, the final scene is analyzed for its sound combinations. Various sounds of different intensities (the drumming of rain, the pounding of hooves, battle cries, the screams of the wounded, the neighing of horses, women’s screams, gunshots) merge into one harmonious sound stream.

The result is an extraordinary combination, Seven Samurai is an excellent example of how to make epic cinema. The professional visual and sound design remains a backdrop, while the foreground features empathetic characters, intense acting, and a timeless story that evokes emotions and leads to reflection.