David Lynch’s DUNE Explained: Strangely Beautiful Disaster

Tacoma – Yakima – Spokane

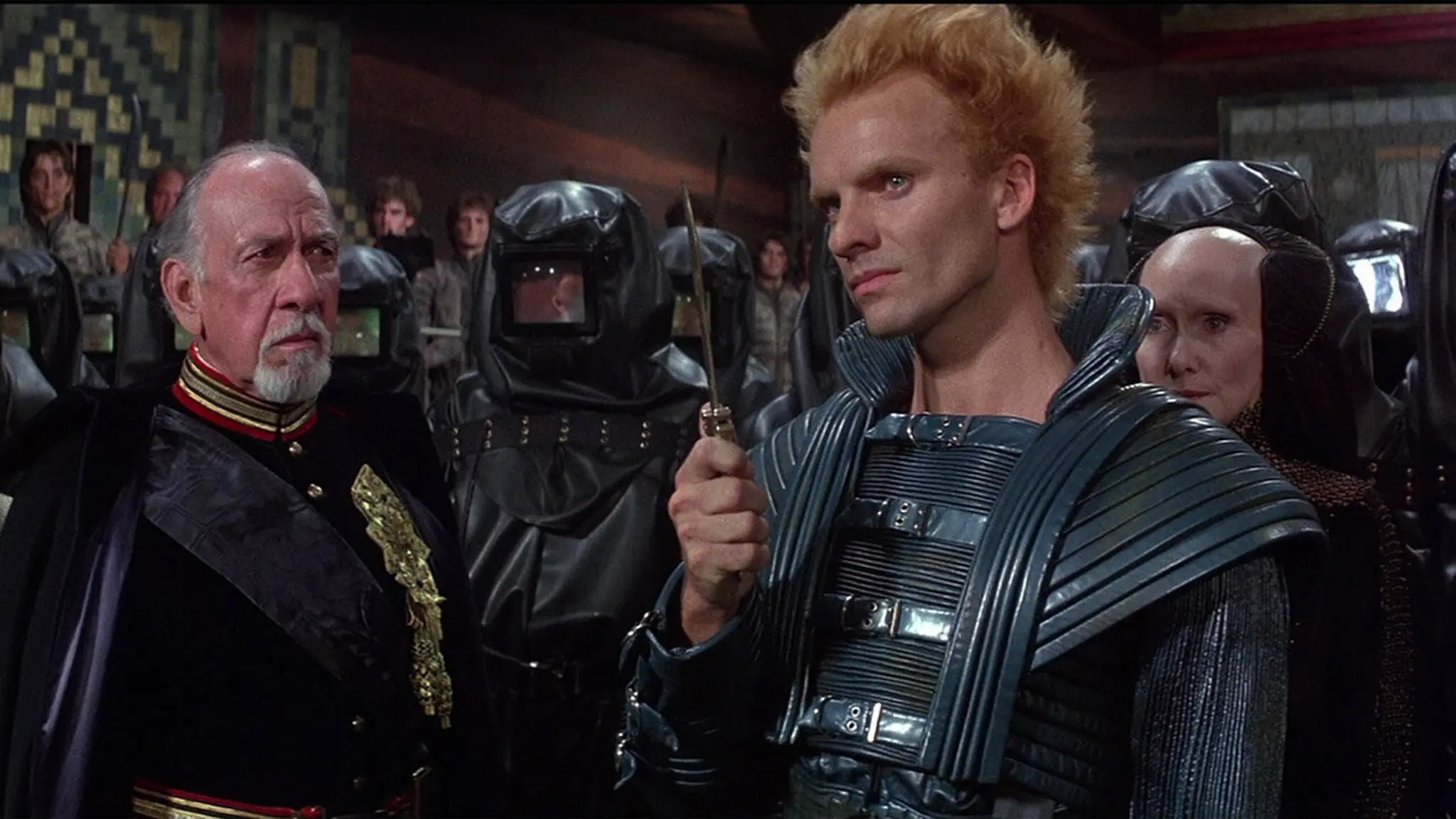

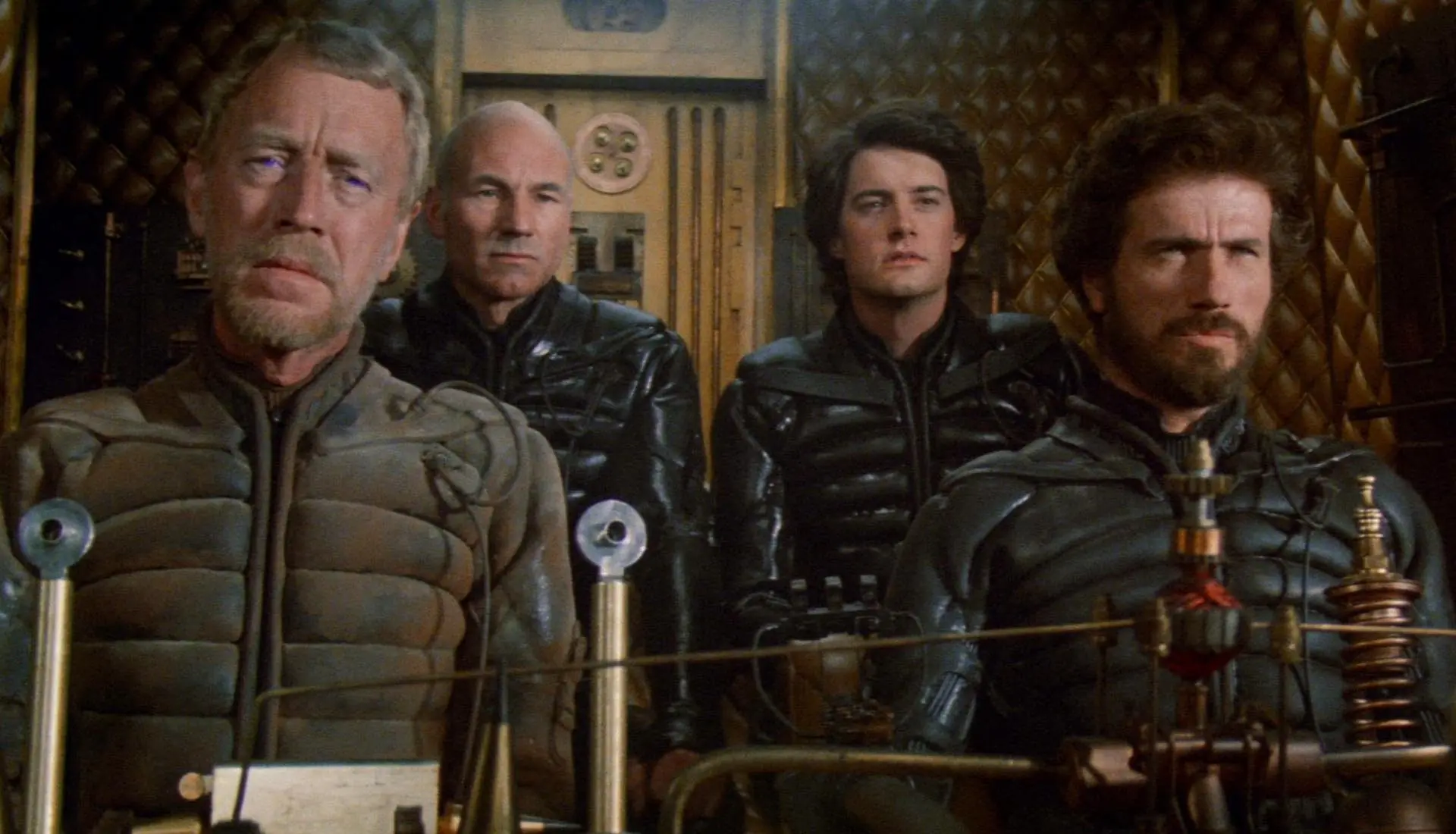

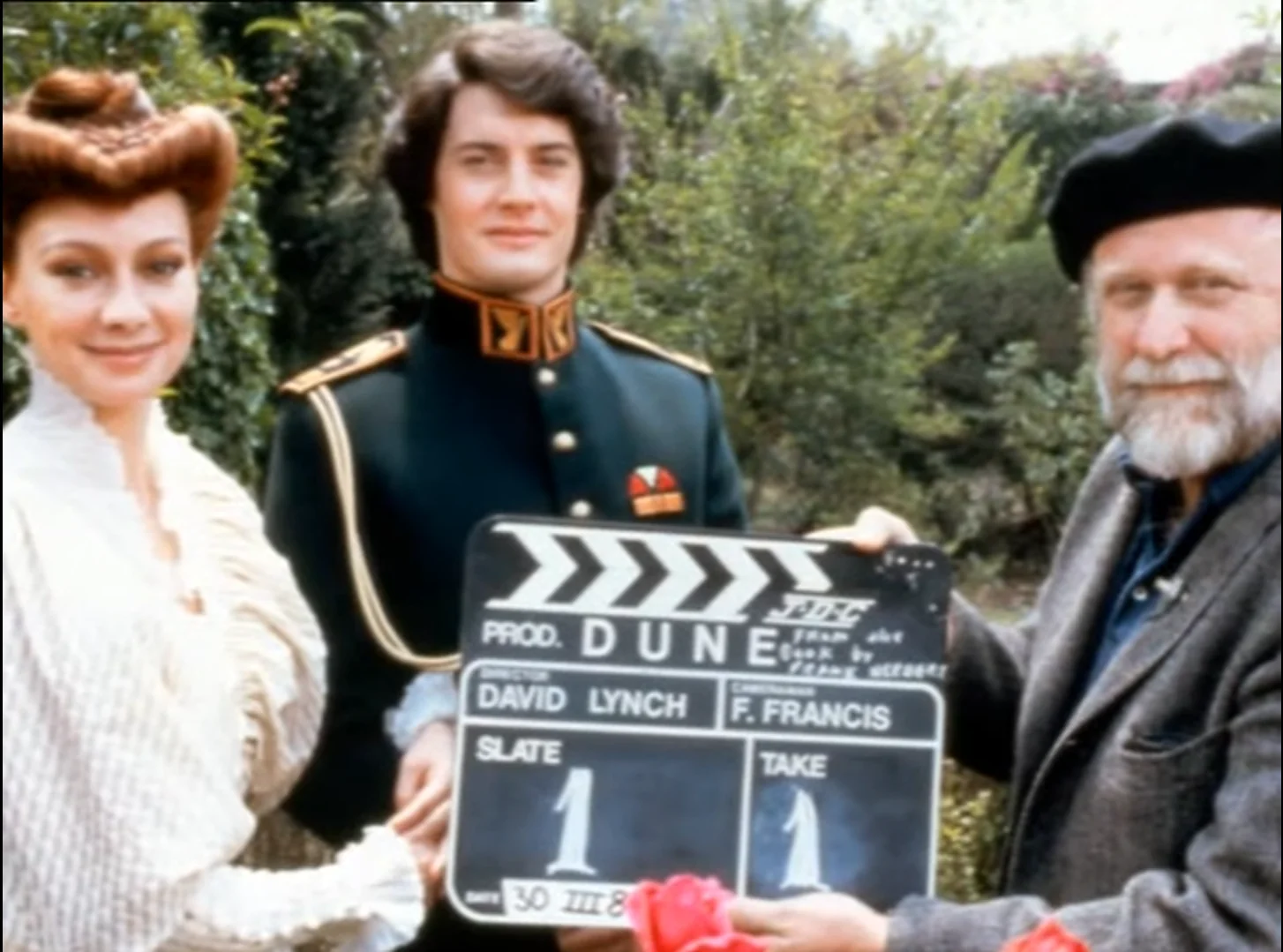

Frank Herbert’s ranch is in Tacoma. Several hundred kilometers to the east, practically a short distance by American standards, lies the city of Spokane, once home to David Lynch. Roughly halfway between Tacoma and Spokane is Yakima, the birthplace and childhood home of Kyle MacLachlan. The actor read Dune at the age of 14, and it became a favorite book of his. In Herbert’s vision, he saw a bit of himself. The desert inhabitants of Arrakis dreamed of one day turning their planet into an oasis suitable for growing plants and collecting water. Yakima, reclaimed by Americans from the desert lands of southern Washington, could evoke the environment born in Frank Herbert’s mind, making it easier for MacLachlan to identify with the novel’s main character. Dune was not the only thing that inspired MacLachlan. During his studies in Seattle, he became seriously interested in acting. Completing the prestigious Professional Actor Training Program opened the doors of theaters to him. While performing in Molière’s Tartuffe, he was noticed by a Hollywood talent scout working for Dino De Laurentiis. She knew that casting for Paul Atreides was underway in Los Angeles. After the performance, she informed MacLachlan about it, assuring him she could arrange a meeting with the director of Dune.

Shortly thereafter, MacLachlan was sitting face-to-face with Lynch, talking about their shared experiences growing up in Washington. They also discovered they were both wine enthusiasts. During the first meeting, the director hardly mentioned Dune to MacLachlan. At the end of the encounter, he handed him the script, asking him to prepare for a presentation of his vision of the role. The next audition took place in Mexico, where MacLachlan performed in Paul Atreides’s costume. After delivering a few lines, he returned to his hotel room, finding a bottle of Lynch’s favorite red wine on the table. A phone call confirming his employment was, of course, a mere formality. Being cast in the lead role of a major Hollywood production was like winning the lottery for the young, unknown stage actor. The success was even greater because many young men were said to have auditioned for the role, including a young Brad Pitt, who failed to capture the attention of the casting organizers and had to wait for his breakthrough, which would come several years after Dune’s release, with Thelma & Louise (1991).

After MacLachlan joined the cast, Dean Stockwell was also hired, who had found success as a child actor but had abandoned show business in the 1960s. His turbulent time spent in hippie communes had caused Stockwell to be forgotten by the general public. His roles in the 1970s were mostly unremarkable, which affected his financial situation. To support his family, he had to work as a real estate agent. When Lynch began filming Dune, Stockwell was on a family vacation in Mexico. He decided to seize the opportunity and visited the Churubusco studio. Upon entering the office, the actor was surprised to find Lynch staring at him, saying he had been almost certain Stockwell was dead. Shortly afterward, he was cast in the significant role of Dr. Wellington Yueh. This performance, along with his appearance that same year in Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas, brought Stockwell back into Hollywood’s good graces.

Under the Fire of Criticism

As work on Dune was nearing completion, a massive marketing machine was set in motion. Before advertising efforts began, the film had cost about $50 million; after the campaign, the budget rose to a then-astronomical $68 million. For comparison, the production and promotion costs of Return of the Jedi were around $43 million. America was going wild. Store shelves were filled with toys related to Herbert’s universe, and the media competed to provide updates on the upcoming hit. Many in the industry predicted that Dune had a chance to break box office records. No one expected that the blockbuster, which took four years to make, would become a financial flop.

Because Herbert’s story had literary sequels, it was assumed even before the release of the first part that more installments would follow. Lynch was in favor of the idea. Kyle MacLachlan even changed his phone number to 547-DUNE. However, the wave of enthusiasm quickly began to wane. Frank Price, one of Universal’s executives, watched the film and felt that audiences would struggle to understand it, which would impact the financial results. Similar opinions, though expressed in a much more blunt manner, came from distributors attending private screenings. Many harsh words were directed at De Laurentiis. Negative opinions about the film began to leak to the media. The marketing machine turned against Dune. The fact that the film had been in the spotlight for months due to the efforts of advertising specialists meant that the media and the potential audience eagerly absorbed every rumor from private screenings. Despite its desert character, Dune began to sink even before the official premiere. When the first reviews from the most influential critics appeared in the press and on television, audiences got the clear message that something was wrong with Dune. Even the usually measured Roger Ebert trashed the film, placing it on his list of the worst productions he had seen in 1984. At that point, the biggest winner was probably Alejandro Jodorowsky, who said he nearly fainted before going to the cinema. The Chilean had seen Eraserhead and believed that Lynch was the only director who could adapt Herbert’s vision better than he could. After leaving the cinema, Jodorowsky reportedly burst out laughing, joyfully repeating that Dune was terrible. Lynch’s failed vision undoubtedly contributed to the mythologizing of the unmade film by the creator of El Topo and The Holy Mountain. If the 1984 production had gone down in history as a genre masterpiece, the crazy idea of the South American surrealist would probably be known to only a few.

Dune officially debuted on December 14, 1984, and was financially and attendance-wise crushed by Beverly Hills Cop. During the first five weeks of its release, the film with Eddie Murphy grossed $122 million in the U.S., while the much more expensive Dune earned only $27 million. Ultimately, in the United States, Lynch’s film barely crossed the $30 million mark. Even when adding the money that came from international distribution, one conclusion is clear: The film was a massive financial failure that significantly weakened the director’s position in the industry.

Lynch never tried to justify his failure, but he still dislikes discussing Dune. It is the only film in his career where he did not retain the right to the final cut. After shooting, the director had over four hours of completed material. Knowing that not all scenes could make it into the film, he wanted to reduce it to three hours. The producers firmly refused. The theatrical version of Dune is two hours and seventeen minutes long, meaning that almost half of the shot footage remains under Universal’s lock and key. Some scenes not included in the theatrical release are available in the 1988 TV edition of Dune. However, it should be noted that Lynch distanced himself sharply from this version and had nothing to do with its editing. The credits replaced his real name with the usual “Alan Smithee” (a pseudonym used by directors who don’t want to be associated with a film). He was also allowed to invent a fictional pseudonym for the scriptwriter, as he was the original author. Lynch took the opportunity to mock the studio executives. The scriptwriter for the TV version of Dune became the fictitious Judas Booth. The figure of Judas needs no introduction, and Booth is the surname of Abraham Lincoln’s assassin.

Lynch has responded to questions about the four-hour version of Dune several times, emphasizing that even if he received the material and could create his version, he doesn’t believe that the story of desert Arrakis would become a better film. He notes that, years later, he realized that Raffaella’s pressure and constant worry over the film’s final length affected the entire production process, distorting the vision at the heart of the script. Lynch’s extrafilmic artistic activity bears witness to how stressful this period was for him. Starting in 1983, Lynch published short comic strips titled The Angriest Dog in the World in LA Reader. The title of the series probably speaks for itself.

A Strangely Beautiful Disaster

Lynch’s Dune is certainly not a typical blockbuster. It’s a much heavier film. The side plots are not always adequately developed. Many elements of the script mysteriously disappear under the weight of subsequent scenes. Viewers demand a return to them, wanting to understand the paths the creator follows, trying to piece together the scattered fragments of the story amid the sands of Arrakis. This isn’t easy and, more often than not, it may be impossible without reading the book. The cause of this lies in the film’s runtime, which constrained the director’s vision from the start. Due to time limitations, Lynch decided to explain many things through a narrator’s voice. Although Herbert employed a similar technique, he had hundreds of pages to craft his intricate puzzle, and paper is undoubtedly more patient than Dino De Laurentiis and the American audience. Looking at Dune in hindsight, it’s the excess of information that constitutes its biggest flaw. The labyrinths present in almost every Lynch film are usually based on the emotions of the characters. Their corridors do not meander through complex plots amidst intricate mythologies. This is the strength of most of Lynch’s movies. Despite their surreal aura, as well as their mystery, cruelty, or absurdity, they always remain very close to the human experience. The world of Dune often distances itself from its characters, drifting toward a realm of ideas too complex to be conveyed in a two-hour screening.

The question remains whether, at the time of its release, the film truly deserved such devastatingly poor reviews. It’s impossible to predict how Dune’s fate would have unfolded if the most prominent names in American film criticism hadn’t buried it before its official premiere. With a film made at such a significant financial expense, every slip can be the beginning of the final downfall. In the case of Dune, the marketing machine unleashed by advertising specialists got out of control, ultimately leading to the premature death of its precious child. With the passage of time, many criticisms of the film seem highly debatable. Richard Corliss from TIME Magazine criticized it for not providing the simple entertainment found in other high-budget science fiction films (remember that Return of the Jedi premiered in 1983). Roger Ebert complained about the film’s general gloominess and odd color scheme, believing that Lynch should have taken inspiration from Lawrence of Arabia and used a color palette more pleasing to the eye for the desert shots (he overlooked the fact that the set designer for both Dune and Lawrence was the same person). But within Frank Herbert’s vision, is there really room for carefree fun and swashbuckling adventure à la David Lean?

The screenplay of Dune was a mess. There’s no denying that. Yet within the narrative chaos lie many intriguing elements that ensure Lynch’s film remains one of the most unique high-budget science fiction movies in cinema history. The universe created by Frank Herbert was unlike the cosmos familiar to Star Wars viewers. His vision of the universe was much darker, less comprehensible, entangled in religious and political struggles between warring factions. The atmosphere Lynch created perfectly captures the essence of the Dune universe. Herbert often, despite media backlash, repeated that conceptually and visually, Lynch’s film reflected his ideas about a world obsessed with the power of a mysterious spice. The rawness of the desert Arrakis, the urban nightmare of Giedi Prime, the extensive use of ornamentation inspired by Egyptian, Arabic, and Venetian art (Lynch drew inspiration from Venetian Renaissance when creating the film’s set design) immerse the viewer in a peculiar, almost hypnotic atmosphere. Because of this, Dune is a very strange and unforgettable experience. On the one hand, its weaknesses are apparent at first glance. On the other, watching the film leaves the impression of something profoundly original and inspiring in its complete uniqueness. That’s why this film, like its literary predecessor, is a kind of challenge. A quick viewing or casual skimming won’t suffice to appreciate Dune. To navigate the dunes haunted by majestic sandworms, you need time. It’s a strangely beautiful disaster.