ERASERHEAD Explained: The Story Behind Lynch’s Masterpiece

Among the audience were the director’s friends and parents, his ex-wife and current wife, his daughter, people from the Institute, and those who had supported the project known as Eraserhead financially over the past five years. After 142 minutes of screening, the lights illuminated the faces of the audience. The room was completely silent, with only the sound of fluorescent lights buzzing.

Jack Nance, the lead actor of Eraserhead, turned to Lynch and said:

See, I told you this film would turn them into zombies.

Moments later, the silence was broken by thunderous applause.

However, not everything went according to the creators’ plans. Even before the private screening, an influential friend of Terrence Malick arrived at the warehouse that housed the film set, editing room, and everything related to Henry Spencer’s world, with the intention of finalizing a distribution deal with Lynch. Unfortunately, instead of a handshake and a signed agreement, the meeting ended in frustration and an abrupt exit. Malick’s friend stood up halfway through the screening, shouted, People don’t act like this! They don’t talk like this! This is nonsense! and left Lynch and sound effects specialist Alan Splet in stunned silence.

Eraserhead wasn’t accepted at Cannes. To get the film reels (12 reels of picture and 12 reels of sound!) to the screenings that would decide the entries for the New York Film Festival, Lynch went to a supermarket and managed to borrow a shopping cart from the manager. He made it on time. The film was shown at 4 p.m. When Lynch called New York three days later, he found out that not a single person was left in the audience during the screening.

A series of setbacks began to discourage Lynch. However, thanks to the encouragement of his then-wife, Mary Fisk, he agreed to try his luck with the Los Angeles festival selection. The couple drove the film reels to the location designated by the festival organizers. The film was screened at midnight. The next day, a scathingly negative review appeared in the respected Variety. But that wasn’t the most important thing.

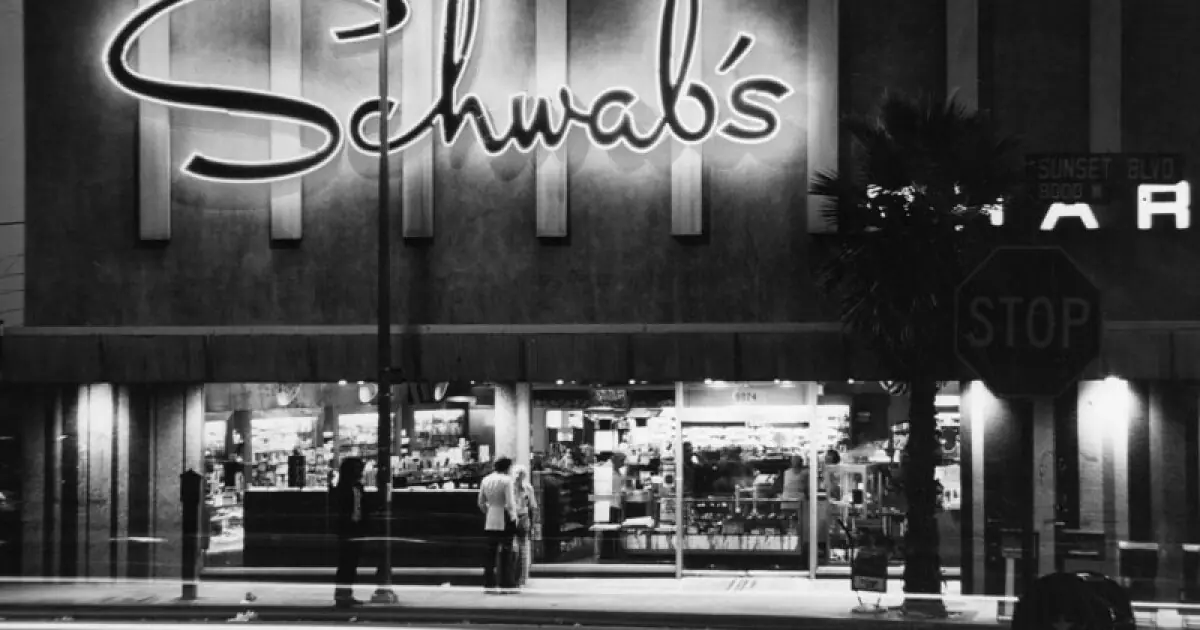

One of the Los Angeles festival organizers mentioned Eraserhead to Ben Barenholtz, who was known at the time as the king of New York “midnight movies.” Barenholtz already had artists like John Waters and Alejandro Jodorowsky under his wing. He was responsible for introducing cult movies like Pink Flamingos and El Topo to American cinemas. The producer quickly decided he wanted to do business with David Lynch. He sent his intermediary, Fred Baker, to Los Angeles. The two men signed a deal at the famous Schwab’s Pharmacy, known for its high-level film industry discussions from the 1930s to the 1950s. Schwab’s Pharmacy also appeared in one of Lynch’s favorite films, Sunset Boulevard, by Wilder. It was a good omen.

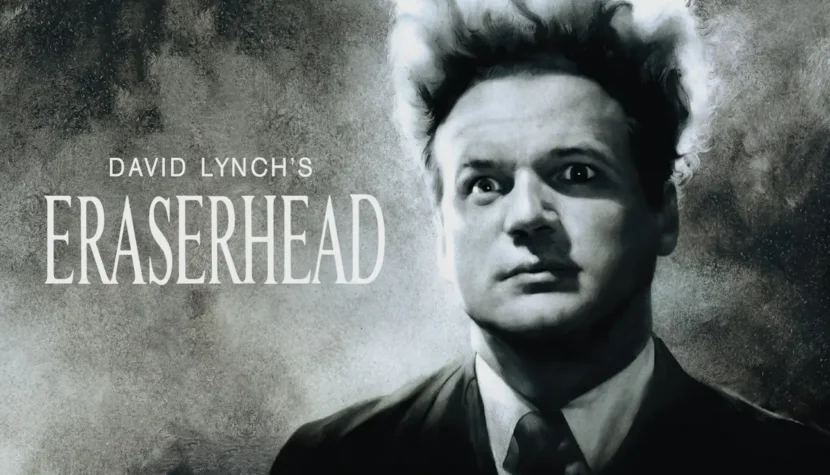

Eraserhead became a staple in the cult “midnight circuit.” Lynch recalls that John Waters himself, during a panel discussion following one of his films, didn’t respond to questions from the audience but enthusiastically recommended watching the film about Henry Spencer. After several years of continuous screenings, Lynch’s debut film became one of the primary symbols of “midnight movies.” The enigmatic face of Jack Nance mesmerized thousands of viewers from posters and silver screens. But how did it all begin?

TOWARD HENRY

In 1970, Lynch completed work on the film The Grandmother. The over-half-hour story transported viewers into a strange and cruel world where parents, acting like predatory animals, tormented their only son. The unhappy boy discovered a seed from which the titular grandmother grew—a woman full of warmth and understanding, the complete opposite of the father and mother. Amidst this dark world, where something evil and unsettling infiltrates the family home, a glimmer of hope emerged. Did it stay for good? I won’t reveal that.

Directing The Grandmother was an extremely important event in the context of Eraserhead. It was during this production that Lynch first started adhering to the principles of cinematic language. His painterly temperament still left a significant mark on the finished production (and always would), but—unlike his earlier works The Alphabet and Six Men Getting Sick—The Grandmother wasn’t merely a formal experiment.

While working on the film, Lynch met Alan Splet, who would later accompany him in creating the sound for Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, and Blue Velvet. Moreover, The Grandmother convinced Tony Vellani and George Stevens (bigwigs at the American Film Institute) that both Lynch and Splet were talents worth bringing to the Dream Factory. Lynch eagerly moved with his family (his wife Peggy and daughter Jennifer) to Los Angeles. However, Philadelphia, his previous place of residence, stayed with him forever (but more on that later).

Splet and Lynch began attending the school affiliated with the Film Institute. Inspired by Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, the director began working on a screenplay for a film called Gardenback. Just as with the Prague writer, Lynch’s story was also supposed to feature an insect as one of the main characters. In Kafka’s work, the protagonist transforms into a bug, while in Lynch’s story, the bug was to be a painful manifestation of guilt that emerged from a “spark” between a man and a woman. This bug-monster would appear in the protagonist’s house, grow, and take up more and more space—a domestic invasion. However, the project never materialized. Lynch lost interest when producers insisted on expanding the 20–30-minute concept into a full-length feature. His enthusiasm further dwindled after the release of The Hellstrom Chronicle (1971), a pseudo-documentary about insects taking over Earth (Lynch felt his idea had lost its originality).

Frustrated with the project’s failure and several school-related incidents, Lynch, along with Splet, decided to drop out. Surprised by the situation, Frank Daniel (the director of the institution and, according to Lynch, the best teacher he’d ever met) summoned both men for a conversation. During the discussion, Lynch shouted that he “didn’t care about the whole Gardenback project.” Daniel then asked what he intended to create instead. The answer was Eraserhead.

BECOMING A FILM

Splet and Lynch found themselves in an ideal situation. Daniel wanted them to stay close to the Institute, so he allowed them unrestricted access to the equipment warehouse. Thanks to the generosity of his friend and warehouse manager, David Khasky, Lynch packed a small film studio into his Volkswagen and set off towards Greystone Mansion, which would become his home for the next five years.

The American Film Institute used the property on Doheny Road as a film studio. When Lynch began working on Eraserhead in 1972, the mansion’s rooms were completely deserted. In the following years, the Institute didn’t mind that Lynch occupied the spaces 24 hours a day. They also didn’t ask for the borrowed equipment back, which Lynch supplemented with professional sound recording and editing equipment (Alan Splet became the head of the sound department). In a way, Lynch and his friends created their own self-sufficient film studio for five years.

However, Frank Daniel couldn’t provide Lynch with the money needed to finish the project. Financing Eraserhead was a challenge for its creators. Lynch invested every dollar he earned into the project. His friends (both those working on the film and those who believed in Lynch’s success) and his father also contributed. The situation was difficult. Eraserhead was shot at night since daylight ruined the film’s visual style, and a nearby park full of daytime activities was a major obstacle. The film crew lived by night, and day was for sleeping. Lynch worked delivering the Wall Street Journal, riding his bike each night for an hour-long sprint to return to Greystone as quickly as possible. The weekly salary from the paper route was $42.

This lifestyle took a toll on Lynch’s personal life. After nearly two years of working on Eraserhead, Lynch separated from his wife Peggy, the mother of his daughter Jennifer. Lynch couldn’t provide for his family, as he spent nearly every cent and every spare moment on the film. When production was paused (this happened several times due to lack of funds), Lynch was often absent, constantly searching for ways to earn a little more for the project. The situation grew so dire that Lynch’s father and younger brother invited him for a “man-to-man talk,” strongly advising him to abandon the project and not to leave Peggy and Jennifer for Henry Spencer’s world. Nevertheless, Lynch decided to finish the film.

After separating from Peggy, Lynch practically moved into the set at Greystone Mansion. He (literally!) slept on the same pillow as Henry, turned on the same lights, and ate at the same tables. The world of Eraserhead became his reality. Friends became his family, especially Jack Nance and Catherine Coulson, who stayed at Greystone almost constantly. Coulson would sneak off to work in the mornings to earn money for the next scenes. Jack and Mary Fisk (Lynch’s future wife), Frederick Elmes, Herbert Cardwell, and the indispensable Alan Splet were always there to help. Peggy continued to support Lynch. The film crew became a family, as evidenced by the recurring names in Lynch’s subsequent productions. For instance, Lynch introduced the concept of the Log Lady from Twin Peaks to Coulson on the set of Eraserhead, long before he even conceived the show’s script.

After five years of struggle and an intense life within Eraserhead’s world, the film was finally completed. Its journey to the screen was covered in the first part of this article. Now, it’s time to cross the threshold of Henry Spencer’s home, and in doing so, step into David Lynch’s mind.