David Fincher’s SEVEN explained

In Seven, as in no other crime mystery I know of, there is an unprecedented manifestation of Evil. Unprecedented not so much because of the enormity of the crime committed, but because of its incomprehensible ambiguity.

Intro

In response to the “hygienic nature” of the European model of the crime novel, as well as in connection with the problem of conventionalizing the content of works, over a hundred years ago the so-called “hard” detective story (also called “black”, although personally I prefer the latter name to refer to works of cinematography). What was the American contribution to the evolution of crime fiction? First of all, the stories will now be placed in the world of social lowlands, ruthless “gangsters”, betrayal, in the fumes of alcohol, cigars and drugs, in the world of prostitution, eroticism and various human perversions. This will be reflected in the language of the novel, which will begin to brutalize, and in the ethical amorphism of the characters. American hard boiled fiction is not puzzle books for polite children from the parish school.

However, there is a well-disguised trap in this reasoning. Although the formal differences between the “European” and “American” schools are clearly visible, nothing has changed in substance: the investigation still shows an undisturbed push for the finale, the detective seems to be balancing, but after all you simply know that he is a noble fellow and a criminal gets behind bars, one way or the other. The focus has simply been shifted from the cool calculation of the detective-gentleman to the brutal threshing of a tipsy sleuth. A fist instead of a magnifying glass, a joint instead of a pipe. It is true that the creators of the “black series” stopped misleading the reader with a simplified, primitively dualistic image of the world, the moral decline of its inhabitants finally began to correspond with the urban abomination that surrounded them, but what if the reader knew perfectly well that the detective must succeed, just as he knew that what he was holding in his hand was a crime novel with an irrevocably happy ending. It can be put as follows: here the author of the “black” crime story makes a tacit agreement with the reader – I will try to make my hero’s triumph not too easy, and you will forget that my hero must triumph at all. As a result, what the “European” model smuggled in veiled and implicitly – the battered law and the controlled ambiguity of the detective’s behavior – the “American” model exposes with lustful satisfaction. This is the end of the dilemma. The detective approaches this imaginary line separating Good from Evil, timidly crosses it, then returns to the “right” side in the glory of the winner, with a studied smirk on his lips, and boasts about his initial ignorance, as if serving a joke. “Are you saying you assumed from the start?” Nora asks her husband, to which he replies: “Actually, I should be ashamed that I didn’t think of it right away.” (Hammett’s The Thin Man). It is therefore easy to be deceived by the provocative revolutionary nature of Yankee crime prose, but looking more closely at these two genealogical trees of literary detectives – American and European – it immediately becomes clear that with all the possible variations of types, their diversity is, after all, something external, perhaps even regional. The difference is only in the polarization of methods – logical thinking on the one hand, wild violence on the other.

Now let’s take Fincher’s film. What determines the uncommonness of this particular movie compared to other crime works? What’s so “anti-criminal” about this crime story created according to sacred rules? This question is justified because Fincher’s film could easily be considered a continuation of the “black” crime story in the spirit of Raymond Chandler. The poetics developed at one time by the creators of the “black” series is realized in the film with obsessive meticulousness: an urban jungle with dark alleys, pouring rain, detectives dressed in long coats with collars sticking out, the dense atmosphere of nightclubs, corrupt cops… These and other features inadvertently place Seven in a series of excellent book adaptations of classics, maintained in the suffocating climate of cinema noir, although the film itself is of course no adaptation – it is the original work of screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker. The problem is that the above-mentioned ingredients are only superficial signs of kinship, a form in itself, without any major substantive aspirations. Seven is different. It’s a sequel where a champion like Chandler would fail to recognize himself. Chandler’s world was populated by individuals of dubious provenance, but on the whole it was also characterized by benevolent irony, it was predictable, elegant and optimistic in its own way, while Fincher’s film focuses on an exaggerated, sometimes macabre image of anarchy and aberrations of civilization . It is a macabre vision in the full meaning of the word, giving the viewer no opportunity to rest from the hustle and bustle of events, almost all of which are far from the commonly understood principles of normality. The point is not that in Seven – as it was clearly shown in Lem’s experimental detective stories – there is no return to the elementary equilibrium of rational cognition. Such a return is possible, indeed, the fact that Evil triumphs and Justice has been deceived does not mean that the world turned out to be unknowable. Here we encounter a similar paradox as in the case of Lem’s Investigation: the pessimistic ending of the film, which contradicts the dogmatic rules of the genre, does not necessarily prove the failure of the knowing mind. On the contrary: the statement that Evil triumphs, although it does not establish a moral equilibrium in us, nevertheless allows us to maintain an intellectual equilibrium, because it is clear what has happened: we have come to know the world and therefore we rule it, and not he rules us. It’s something completely different. In Seven, as in no other crime mystery I know of, there is an unprecedented manifestation of Evil. Unprecedented not so much because of the enormity of the crime committed, but because of its incomprehensible ambiguity.

Related:

The city

Its labyrinthine structure, built of narrow streets, treacherous passages and tightly adjacent buildings, effectively intensifies the claustrophobic impression, emphasizing the depressive and unfriendly atmosphere of the place.

The fact that the plot of every solid detective story should take place in a closed space, separated from neighboring areas by a tangible physical barrier, is one of the fundamental distinguishing features of the genre. Not so with Seven. Everything, from the discovery of the first victim (a fat man dipped in spaghetti sauce), through the subsequent stages of the investigation, to the recognition of the perpetrator, proceeds without the slightest external interference within the limits of the big juggernaut city. Seemingly, the exception to this rule is the final confrontation in the desert, but only apparently, because it will take place only after the criminal is recognized, not earlier. Therefore, we have no choice – we will spend most of the time in a multi-million metropolis, watching the police wrestle with a serial killer, and the scenography specialists who created a truly repulsive vision of the city made sure that the journey through the city corridors was not a pleasant experience. Its labyrinthine structure, built of narrow streets, treacherous passages and tightly adjacent buildings, effectively intensifies the claustrophobic impression, emphasizing the depressive and unfriendly atmosphere of the place. Hovels with dilapidated plaster, tenement houses falling into disrepair, waterlogged courtyards, all this insistence in illustrating ugliness add up to a general scenographic ugliness, additionally constantly poured with streams of heavy rain. Despite the general disgust that accompanies us while moving through the alleys of the city, one cannot deny the artists’ artistic sophistication: the picturesqueness of the frames here is as indisputable as their exposed hideousness, and the ugliness of the urban landscape often attracts with its peculiar sophistication. This way of imaging is, of course, not a proprietary invention of the creators of Seven. If I had to pick a song that immediately preceded Fincher’s aesthetic endeavors, it would be Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. The resemblance is striking – some frames from Fincher’s film seem to be cut out of Scott’s movie.

What goal – apart from the strictly aesthetic one – guided the creators when they decided to set the action in such an extremely repulsive environment? All in all, one might as well ask what was the purpose of the “black” detectives when they relocated their detectives to the cities – it would come out the same. First of all, the city is associated with a labyrinth, and the big city crowd makes it harder and harder to find a criminal, because it is also easier to hide in the human thicket, break ties with others, become anonymous, cover your tracks. It’s not without reason that the movie killer is named John Doe. In the US, this is used to refer to men with unidentified or hidden identities. In another sense, “John Doe” is also an ordinary, gray citizen. That’s first. Secondly, the rotten urban staffage fosters a purely functional need to humiliate the defenders of the rule of law. I’m already telling you what it is. Well, the law – according to the above line of reasoning – should first be severely mocked, so that later it could triumph in the blinding glare of the police badge. For the more overwhelming the crime and the more insolent the criminal, the greater the satisfaction when, pushed to a desperate defense, the trampled law will rise from its knees, and the relentless tracker of evil will catch the vile villain. The game is therefore about the spectacular victory of the social sense of justice, understood in terms of retribution for the harm done. This is the axiology characteristic of the classic detective story, which has never, let me emphasize: never, been abandoned. Does Fincher’s film deliver on these promises? The style of film noir was needed by Fincher to bring to the fore the content that rested deep below the deck of hardened and long-dead genre norms. Fincher does not argue with the achievements of the “black” detective story – he only exaggerates the degenerations in the orbit of his interests.

Somerset and Mills

The prologue of Seven is expository: it serves to introduce the drama’s two leading characters to the stage, as well as to present the scenery against which the main intrigue will take place.

The film opens with scenes in Somerset’s apartment. The hero is getting ready to leave. He knots his tie, grabs his badge and switchblade from the table, brushes a speck of dust off his jacket, turns off the light, then cuts to the inside of a grime-slick tenement house. Somber atmosphere. A corpse lies on the floor, a shotgun next to it, a splatter of gore on the glass. Somerset looks at the drawings hanging on the refrigerator door. His innate inquisitiveness evokes sincere reluctance among colleagues, the prospect of imminent retirement – genuine relief. This is said directly, without hypocrisy, thanks to which the detective grows in our eyes to the rank of “the last noble cop”. He immediately evokes sympathy mixed with compassion. Originally, the film was supposed to start with a scene in an old cottage in the countryside. It’s a good thing it didn’t make it into the final edit. The soothing silence of the landscape and the frames bathed in the glow of the afternoon sun, instead of introducing the viewer to the soulless atmosphere of the urban jungle, would rather promote reflective stupor. It would be an unbearable dissonance, a flaw in the film’s emotional fabric, given the ironclad consistency of its later parts.

The second most important character in the film is David Mills. A young, lively and outspoken detective at first does not find common ground with a more experienced and subdued partner. Somerset treats him with fatherly severity – like a surly son who prefers talk to the art of listening. He relates to him as if he were talking to a rookie who still needs to be trained, acquainted with the secrets of the police craft. This may not be a revolutionary observation, but it is significant because in almost every police film, the friendship between the partners is always born in the fire of misunderstandings (regardless of gender).

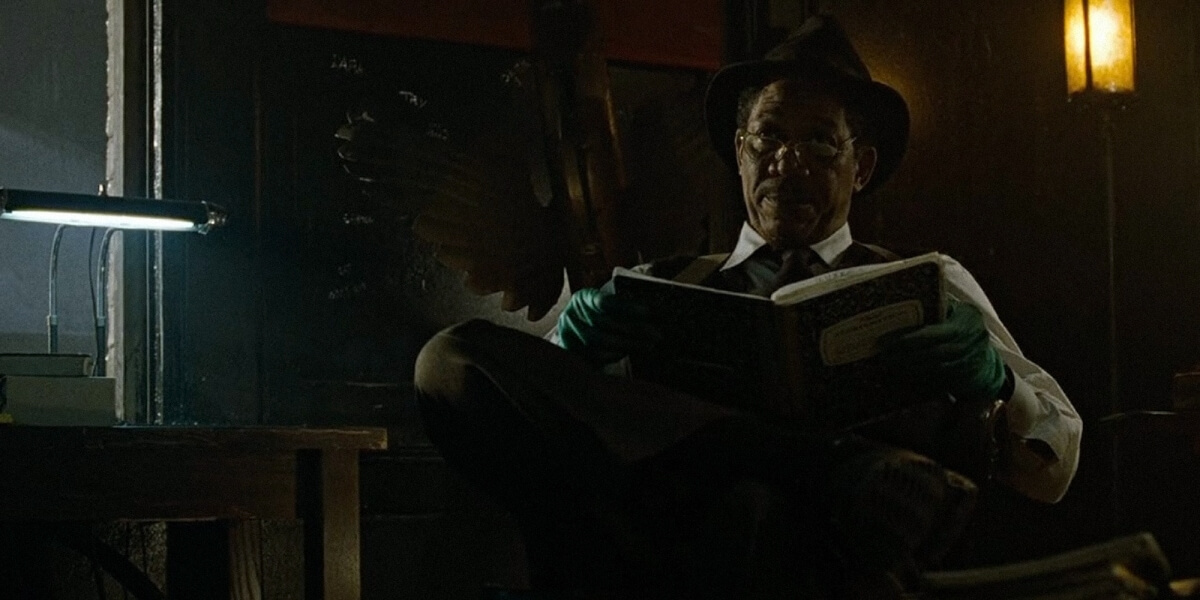

The prologue of Seven is expository: it serves to introduce the drama’s two leading characters to the stage, as well as to present the scenery against which the main intrigue will take place. The audience must assimilate a few names, as well as learn elementary features on the basis of which it will recognize the acting characters. We, in fact, relying on fragmentary information, could give a pretextual characterization of both detectives. The rest of the movie will only confirm these initial assumptions. Thus, Somerset is not significantly different from the literary characters we know: he is an “old-fashioned” detective (avowed chess player, reads a lot, uses an antique typewriter at work, shuns television), he has much of the policeman-scholar in him who leaves precinct space for the sole purpose of investigating a crime scene, which thoroughly interrogates suspects by asking tricky questions, which captures significant details at a glance, and then arrives at a solution without having to engage in risky firefights or daring chases after a fleeing criminal (this role will go to Mills). Somerset is simply an aged sleuth who compensates for physical deficiencies with the innate ability to associate seemingly distant facts. His sense is smell, and victory is the triumph of reason. In the case of Mills, however, we are dealing with a complete reversal of the hierarchy: what for Somerset was the quintessence of investigative work, for Mills becomes unnecessary ballast restricting freedom of movement. Self-confident, reckless, he prefers spontaneous action to idle sitting behind a desk. He despises paperwork; as a rebellious soul, he often comes into conflict with his superiors. Mills is, in a way, an heir to the tradition of police cinema, which requires investigators to make up for what they lack in experience with cleverness and eloquence. “You’ll talk. Get those golden lips of yours to work,” Somerset will say as they both stand at the door leading to John Doe’s apartment. By the way, in Somerset’s creation I miss something that could be described as “the last brushstroke”. I miss him that craving for alcohol, which was manifested, for example, by Chandler’s characters. Chandler’s private detectives were constantly moving under a slight “buzz” – drunk, but still able to drive a car. There was a lot of unspeakable nonchalance about it: a jaded detective with a few days’ stubble, a glass of brandy “for the sake” on the table, a dying cigarette in the ashtray.

The clash of two such completely different characters – apart from the fact that it is not very likely to exist outside the film: after all, psychological tests in the police are not done to combine fire and water – must provoke tension. This is a trick as old as the cinema itself, exploited to such an extent that today it is probably only suitable for parody purposes. Meanwhile, among the creators of, let’s call it working, “light” police cinema, it still enjoys unflagging popularity. The hackneyed pattern: sedate cop – hotheaded cop, stubbornly copied by countless Hollywood screenwriters, is usually calculated to evoke a specific reaction in the audience. And at this point I am forced to interrupt the argument with another digression: Seven has absolutely nothing to do with the atmosphere of noncommittal sensationalism with mocking overtones. It’s a completely different league, a different weight category. Fincher’s film is definitely closer to the extremely dark aura of Friedkin’s Cruising. My point is that the humor in Seven, evidently present as if between the lines, does not serve to soften the horror pouring out of the screen or to reduce the tension. We will not find in Fincher’s work cheerful dialogues that could be considered a safety valve, allowing a man to breathe and regulate his pulse before the next act. On the contrary: it is a very discreet humor, devoid of verbal fireworks, extremely raw, so raw that we are afraid to smile. In this regard, the consistency of the film is admirable, considering the fact that wit has now become a mandatory ingredient in almost all similar productions.

John Doe

This guy is methodical, thorough, and worst of all, patient.

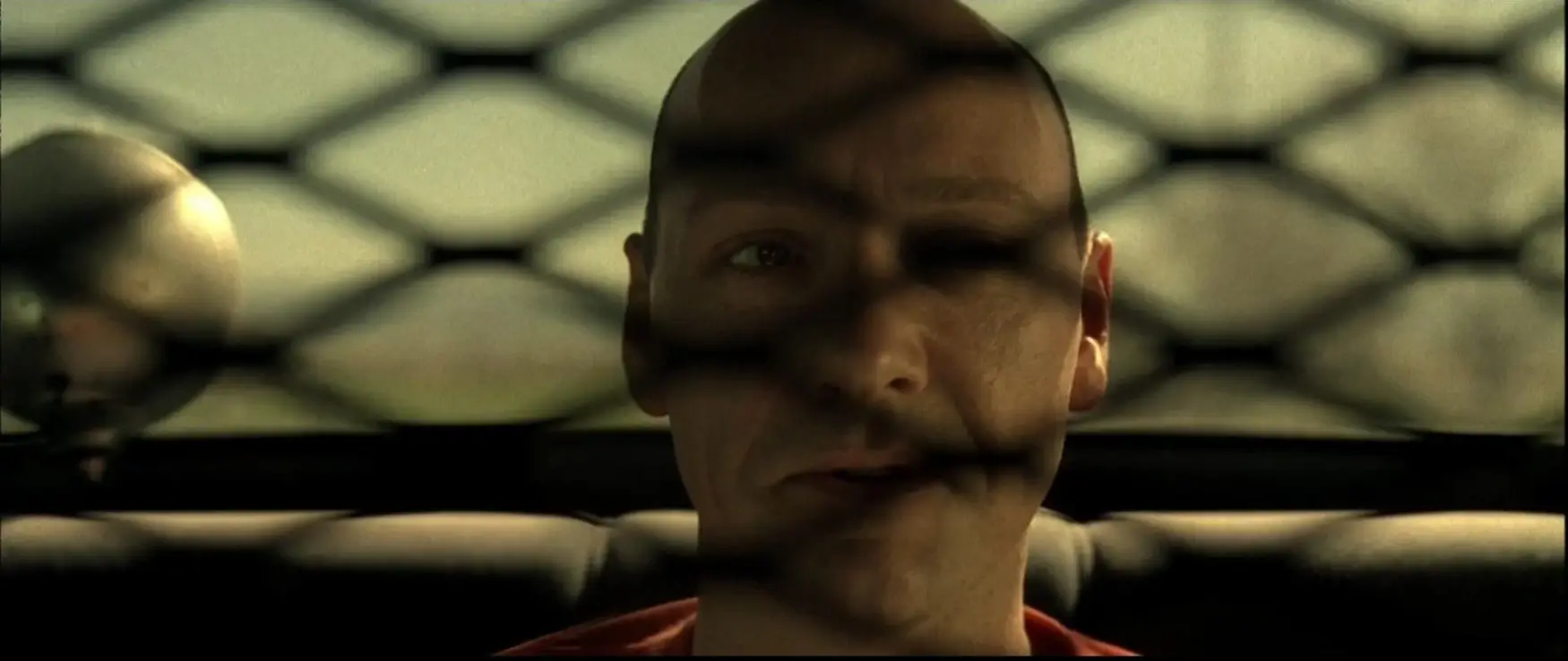

It is significant that the detective story avoids serial killers like the plague. The maniacal murderer can be tracked down, cornered and apprehended, but it is difficult to wage an intellectual duel with him, which is the basic duty of a novel detective. No psychic aberrations can take away from a murderer the privilege of thinking and acting logically. And they don’t answer. Suffering from mental deviations, the murderer immediately provokes the public’s opposition. The audience – generally hostile to any manifestation of mediocrity – does not like to watch “ordinary” psychopaths in action (Angst by Kargl, Man bites dog of the trio Remy Belvaux, Andre Bonzel and Benoit Poelvoorde), prefers to follow the actions of outstanding crime artists who work for two hours for slightly higher motives than a damaged chromosome or the parental overbearing stepfather. In Seven, John Doe becomes such a self-proclaimed preacher. Sticking to the canonical rules of a criminal charade, the director will reveal his face to us only at the end of the film. Another thing is that it will take place in circumstances that are far from the usual pattern, but more on that later.

The prototype of John Doe – and in this case my intuition borders on certainty – was John Ryder (Rutger Hauer’s memorable portrayal), murdering drivers in Robert Harmon’s The Hitchhiker. Man from nowhere – overly mysterious and disturbingly effective. An interesting fact is that at one point in Seven there is a line that sounds like a paraphrase of a statement from Harmon’s movie. What’s more, it happens in analogous conditions – at the police station, right after the criminal’s capture, and in both cases the line is spoken by the police captain, standing in front of a Venetian mirror and watching the suspect sitting at the table in the interrogation room. At Fincher: “We didn’t find a single good print. … He didn’t take loans. No sign of employment. All we know about this guy is that he’s rich, well-educated, and completely insane”; Harmon: “No criminal record, no driver’s license, no birth certificate. We ran his prints into the computer and found nothing. We don’t even know his name yet.”

John Doe also shares a special kinship with another psychopath – Dr. Lecter from The Silence of the Lambs. And it’s not about the passion for sophisticated torture. Both of them are of considerable intelligence, which fits perfectly into another criminal template – a photogenic murderer with above-average erudition. Both also bear all the hallmarks of fiction detached from life: a brilliant murderer, acting extremely bestially, acting not out of material needs, but out of sentiment for art, because he does not take into account the fact that he could make money from his wicked dealings. World criminology is suspiciously silent about individuals who compose crimes the way Wagner composes symphonies, but film (and literary) fiction is by far the least concerned with this argument. What keeps the audience sitting on the edge of their seats is the cerebral precision of the guy’s criminal actions. “This guy is methodical, thorough, and worst of all, patient” (Somerset). The phenomenon of the mechanical side of the murderer’s madness is puzzling, the derivative of which is not, as one might expect, ubiquitous anarchy, but an excess of rigor. From reading experience, I know that crime tends to complicate the simplest things, almost always requires a huge amount of eye-catching apparatus, and for this reason alone it must come to light. Rarely in crime fiction is the crime committed in prosaic conditions. It should be rather muddy and overly complicated. And it is already the peak of dreams if it seems to be a challenge to common sense. This has its good sides – crime as an intellectually and technically sublime construction usually self-destructs by its own ever-increasing confusion. The problem is that the undeniable absurdity of Doe’s actions, instead of loosening the knots of logic, gives his actions the features of a macabre system. Doe does not make uncoordinated movements. A spontaneous gesture excludes diabolical machinations. Pride, greed, impurity, envy, gluttony, anger, laziness – this is the bulleted pattern by which John Doe chooses and murders. Clarity worthy of a mathematical equation.

The storm

Doe manifests his absolute dominance over the world of law.

Already in his full-length debut (Alien 3), Fincher proved that he is extremely efficient at blowing up existing patterns. There is a scene in Seven when, after many days of continuous downpour, the sun finally peeks out from behind the clouds. Around the same time, a taxi pulls up to the police station. A man in a bloodstained white shirt climbs out of the car. What will happen in a moment will be the final nail in the coffin of a classic detective story: here, of his own free will, the wanted murderer crosses the threshold of the police station and, with an expression of a mocking smile on his face, allows him to be put in shackles. I didn’t expect such a poker move from the director. My surprise was no less than that of the film characters, because nothing that had happened earlier foreshadowed such a radical turn of events. The scene in which the criminal appears at the police station is a key, climax of the plot – it is then that the whole lacy structure of the crime story falls to pieces, and a viewer like me is suddenly jolted from a blissful state of contentment and put on the defensive, at the same time losing control over the action. Emotions run high. The armor-piercing principle of the crime story that we reach the criminal from the circumstantial evidence ceases to apply in Seven when Doe crosses the threshold of the police station. Reason capitulates. Doe’s advantage over police officers is not an ordinary advantage, well known to us from hundreds of other crime stories. When Doe decides to confuse the chase by giving the police a clue in the form of fingerprints imprinted on the wall, he simultaneously sends a signal that these and other tricks should be treated only in terms of a cunning game between the criminal and the detective. But when he visits the station with brash bluntness, the game turns into a manifesto. To put it bluntly: by appearing at the police station, Doe manifests his absolute domination over the world of law. Immovable and uncompromising in what he does, he grows to the size of a symbol of impunity.

The mystery

The structure of the world presented in Seven is quite similar to the architecture of the old mystery scenes.

Czesław Miłosz, The Noble Prize, winner once wrote that when complaining about the earth as the vestibule of hell, we should consider that it could be complete hell, without a single ray of beauty and goodness. It is very likely that Fincher managed to model – like Orwell in his time – such a perfect, global and frozen image of Evil, an image that has not been portrayed in such black perfection for a long time in cinema. The director made a monument out of the dispersed and incipient Evil, he built a reality of boundless lies and boundless violence, in which the right is not on the side of the victim, but on the side of the torturer. In this sense, Seven is an implacable film with which the final result is not negotiated.

The determinants of a criminal work used by Fincher and the simultaneous depiction of Evil that does not fit in such a convention, as well as the observational range covering civilization, discreetly hint at the existence of the film’s intellectual background, which shines through the facade of criminal acrobatics. This background will be the ancient mystery tradition. This means that the structure of the world presented in Seven is quite similar to the architecture of the old mystery scenes. It is enough to glance once at any work from the Middle Ages to see how strongly universalist aspirations their author had – the desire to describe the cosmos in one sentence, with one stroke of the pen, is evident in almost all texts of the era. In the medieval mysteries, the whole universe was presented as it was understood by Christianity. The theater showed us heaven together with heavenly spirits, earth, i.e. the proper stage, the circle of human activities, and hell, imagined as the mouth of Satan, from which representatives of evil came out – evil of all kinds, from betrayal to buffoonery. Thus, the mystery presented a coherent and comprehensive picture of the cosmos. When examining the presence of mystery in Seven, one should first of all answer the question of whether and to what extent Fincher’s work implements the project of the whole, which is significant for the poetics of the mystery.

The action of the film takes place in an unspecified space of the modern city. One would like to say that it is suspended as if in “historical timelessness”. Only the titles of individual chapters prove that the plot events take place within a week. The number “7” organizes practically all parts of the film, as an ordering element it is also a carrier of meaning. Other than this sparse mention, we have no further clues. The lack of precise nomenclature and specific time of action suggest a parabola. This is, of course, deliberate, with an established tradition in literature (not to look far – Kafka’s novels). The conclusions are self-evident: the arena of events taking place in the film will be the whole world, and this world as such will become the field of one thing – the constant struggle between the forces of Good and Evil. Going a step down, we come across important details. I have already mentioned it when describing the scenography: everything is rotten here, both in the physical, moral and, more broadly, ontological sense. The interiors are dark, gloomy, hostile, dominated by sad browns and faded greys. Apart from the rottenness and the ominous howl of police sirens, the city has nothing to offer, it breathes morbid ugliness, it is as if stigmatized with dirt, which begins to play a symbolic role – suggests the second of the three levels of the mysterious structure: Hell. The characters themselves obsessively emphasize this parallel. Mills’ wife, Tracy: “I hate this town.” Somerset, when asked by a taxi driver where he wants to go, replies: “As far as possible from here.” Another scene, this time in the interrogation room. Mills grilling the brothel owner where a young woman was murdered, asks the guy a seemingly trivial question: “Do you like what you do? The things you see?” The visitor replies with disarming honesty: “No, I don’t like it. But that’s life, isn’t it?”

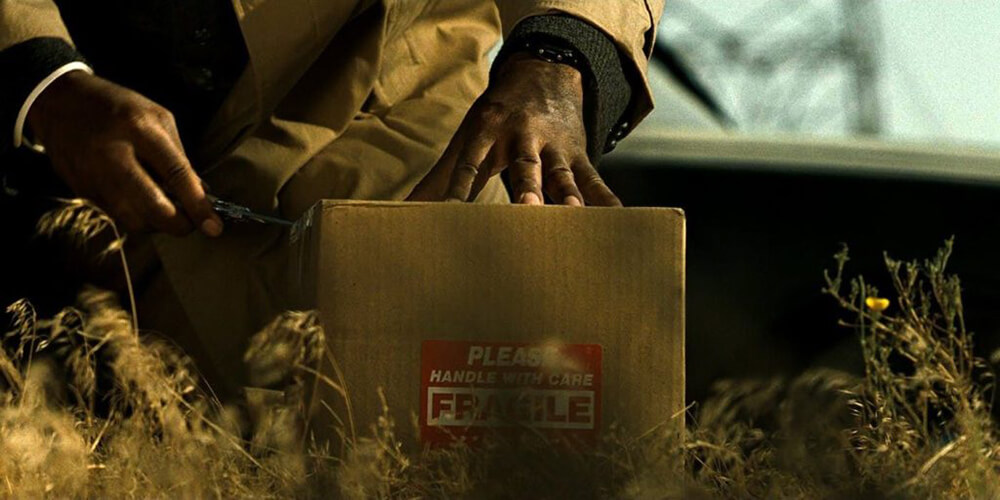

That’s life. These words, like a gloomy echo, will accompany us until the very end of the film. Truth overwhelms here with its brevity, it comments on existence in one sentence, launches a pessimistic interpretation of existence as vanity. In almost every utterance there is a longing for something better. And just as quickly it bends under the pressure of ruthless laws governing the urban reality. Murders, rapes, thefts, robberies – here is the world frozen in chaos, completely devoid of any traces of God’s presence, the world undirected, extremely opposed to the mystery space; it is a mechanism that has jammed, derailed, jumped off the tracks. The reality of Fincher’s drama is not a mysterious whole seen from the transcendent perspective of God. The battle with Evil is stripped of the remnants of pathos. The sky here is so distant that it is practically inaccessible, as if covered with a tight layer of lead clouds. The coherent image of the universe is crumbling. On its ruins, a phantom world instantly grows, fragmented, dead, founded on nothingness. And even if we agree that the Mills apartment, and the library, to which Somerset is so relieved to go after work, may pass in the popular consciousness as a kind of “vestibules” of heaven, they will still be only vestibules, and they are constantly exposed to to the vulgar attacks of the reality of the City external to them. Mills’ wife dies at the hands of John Doe, brutally murdered in her own apartment. The criminal will then not hesitate to chop off her head and send it to Mills packed in a cardboard box as a gift. The guards in the library play cards to pass the time to the accompaniment of J. S. Bach, one of them says that – here’s a quote – “Culture comes out of his ass.” The crime is incomparably smaller than the bestial murder, but let’s remember that we are currently on a mystery level, where even seemingly trivial words spread with powerful reverberation. It is worth paying attention to something else, a proof of the director’s uncommon intuition. The interior of the Mills apartment – always warmly lit, filled with soothing peace – is shaken from time to time by the rumble of the subway passing nearby. I read this signal as follows: the desire to be in an orderly space is great, but the fulfillment of this desire turns out to be impossible. Harmony is a wonderful delusion, a utopia set up by a desperate man, for there is no escape from the outside. You cannot live in the City and outside of it at the same time.

Angels

In the face of Evil spreading with impunity, the heroic effort of the advocates of the Law turns into a silent scream.

Looking at the film from a “mystery” perspective, Somerset’s retirement after years of service and his intention to move to an old cottage in the countryside cease to be just an empty realization of a faded slogan about a detective who will solve the case only when he is removed from it. This clichéd interpretation is exhausted when we leave the criminal props room. The act of retirement, the privilege of the aged detective, suddenly takes on a revealing meaning – it is tantamount to a moral capitulation, a bitter admission of powerlessness (Mills: “You’re leaving not because you believe what you say. You want to believe it because you’re leaving”) . We have now reached such a point of analysis that it becomes necessary to revise the functions of all the characters in the film. Looking at Somerset from a different angle than before sharpens those features of him that have so far remained hidden. The hero will therefore be, according to the new nomenclature, “The Descending Angel”, a divine messenger who has strayed from the route marked out at the beginning. Having been on Earth for a long time (I will use the words “Earth” and “City” interchangeably from now on), he managed to feel the “dirt” of life on his own skin, immersed in the fetid swamp of callousness and cynicism. Apathetic, washed out of illusions, he treats settling in the countryside as the only reasonable alternative. But the earth’s mud cannot simply be washed away. Sitting on the couch in the waiting room, next to Mills, who is getting ready for a nap, Somerset will give a wry, poetic monologue – it will be a summary of his escapist, decadent attitude: “We collect remains, we collect evidence, we photograph, we analyze. We log it all and record the time of events ( …) We put them in neat little piles and put them on file. Maybe we’ll use them in court someday. We collect diamonds on a desert island, storing them in case we’re saved (…).” There is a note of bitterness in every word. The city has sucked Somerset’s last life-giving juices, it has taken away from him not so much his enthusiasm for work – for it is gradually fading away, giving way to routine – it has taken something much more valuable from him, namely, his confidence in the success of the mission he undertook once, long ago, as a young policeman, accepting the badge and taking the oath of allegiance. In the face of Evil spreading with impunity, the heroic effort of the advocates of the Law turns into a silent scream.

The natural counterweight to the beleaguered Somerset is Mills, sticking to the established terminology – “Ascending Angel”. He appears in the City unexpectedly, as if knocked down from Heaven to Earth. He confesses to his partner shortly after arriving: “I just got here and they already put me in here.” – “One thing I don’t understand: why here?” Somerset replies, surprised that he chose this particular place for his service. We slowly see that the standard duo of detectives transforms into a not trivial carrier of mutually complementary values. Somerset is prudent, just and moderate. Mills shows bravery. Four main virtues. A wreath of the most coveted ancient qualities. Only the biblical triad is missing. When added together, we get seven. The plus and minus of this world, a recipe for a dignified life, although not necessarily happy and pleasant. This pantheon of seven virtues is the only axiologically stable element in the entire film (apart from Mills’ wife, about whom in a moment). This monolithic structure of values will be contrasted later by John Doe, assisted by the seven deadly sins, fulfilling the classic postulate of a symmetrical composition of the work and revealing the second face of the mystery reality. Tracy deserves a little more attention if only because she is the only active female character in the film. And if she was merely a neutral figure for the detective story, i.e. the detective’s wife, deprived of the tempting and treacherous charm of a model femme fatale, she already plays the first violin on the mystery scene. She arranges the dinner, during which Mills’ relationship with Somerset finally solidifies, going beyond the framework of purely business contacts; she provokes Somerset to reveal tragic events from the past, when he forced his woman to terminate the pregnancy; and perhaps most importantly: Tracy is pregnant. Pregnancy, of course, has a symbolic meaning here, it emphasizes the heroine’s blessed state and seals her belonging to the kingdom of virtue. When in the finale, just before the execution, Tracy’s face flashes on the screen in the form of a single frame, everything suddenly becomes clear: the woman in the picture is the truest angel: shrouded in white, posing as an ephemeral woman with pale skin and slightly flushed cheeks. The embodiment of the ancient ideal of Beauty, Good and Truth in one person. Chopping off her head, Doe will ostentatiously announce to us his undivided dominion over the world. He will do the same in the scene at the police station: here he will humiliate the law, there he will humiliate Good.

The evil one

Evil spreads like an ink stain on blotting paper, mercilessly taking over more and more areas of humanity.

John Doe is the most enigmatic character in Fincher’s film. While qualifying him to the circles of hell does not cause many problems, assigning him a degree in the hellish hierarchy is.

If Evil were ever to materialize, it would probably take the shape of an “ordinary” man to disguise. It could easily be a college professor, the plumber who fixed the leaky pipe under my sink, or the neighbor across the street who helped the old lady across the road and who graciously let people get out of the elevator. For if Good is heroic, Evil must be cunning. John Doe’s every move is the product of cold calculation. The hero moves every day among props with a positive sign of value: on his shelves we will find rows of fat volumes, including the titanic works of St. Thomas, in the drawer – a Bible and a rosary, on the floor of the crucified Christ, at the head of the bunk – a neon crucifix. The kitsch of these decorations is mixed with their sacred purpose, which only intensifies the feeling of debauchery. John Doe can do anything: he knows Milton’s Paradise Lost, boasts of reading Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, and quotes from Dante’s The Divine Comedy from memory. But despite this freedom in communing with the elements of the sacred, the murderer wears off his fingertips. At the criminal level, this will be an obvious form of protection against leaving fingerprints at the crime scene. On the mystery level, however, it can be a method of avoiding direct contact with the sacred. One way or another, Doe moves in the space that we would call the space of high, anointed culture, and what’s more, he does it without much embarrassment. Even torturing and mutilating his victims, he has selected scenes from Dante’s Purgatory before his eyes, with a small remark here – he does not imitate them, but pastiche them with grotesque artistry. As we know, in Dante’s sinners, penitent for laziness or gluttony, ran aimlessly, getting stuck in the bloody mud, penance required them to move. Meanwhile, in John Doe’s gruesome theater of torture, sinners lie or sit tied to beds and chairs with ropes; instead of renouncing indolence, they “decay” like one of the victims of the Doe’s activities, drug dealer Victor detained for a year in a horizontal position; instead of driving away the temptation to eat, they gorge themselves to indigestion, eating until their stomachs burst. The question is, why this staging straight from a tiresome nightmare? Why all this mess of piss and blood? All that iconoclastic staffage? In my opinion, this is the perverse logic of these sermons, it is about turning reality around, blurring its contours as much as possible, turning everything upside down, with the lining up. As Doe himself admits, “He turns sin against the sinner.” This truly “twisted” vision of the world, and at the same time the true nature of the criminal, will come to light in the penultimate sequence of the film, or more precisely – in the car driving scene.

Mills in the passenger seat, Somerset at the wheel, Doe chained in prison uniform in the back seat. His face is reflected in the rearview mirror. Hounded by detectives, the murderer finally starts a polemic. He spreads his own proposal for Hell in front of them. He is very vulgar, i.e. using demagogic tricks, he vulgarly appeals to their life experience, he wants to convince them at all costs that humanity suffers from an incurable form of moral gangrene, that everything that surrounds us is completely depraved and corrupt. Using a sledgehammer, he tries to force his listeners into their heads that the world is a gutter in which Evil spreads like an ink stain on blotting paper, mercilessly seizing ever new areas of humanity. A devastating diagnosis. It is difficult to accept it, considering that it contains some peculiar significance, based on the categorical verdicts. It creates a ghostly rhyme with Somerset’s laconic tale of a man whose eyes were gouged out because he refused to give his attacker his watch. Despite all this ambiguity, the senior detective tries to treat Doe’s statements with a great deal of reserve, cum grano salis, with distance. His questions, very cunning, are dismissed by the murderer with a biblical phrase about God’s inscrutable judgments. In order to fully understand the strategy of the criminal’s character, one thing must be realized – namely that John Doe is first a representative of Evil, and only then acts as a preacher. In practice, this means that he will sooner combine truth with falsehood than generously expose the mechanisms of lies. Doe uses his tongue like a snake – biting and spitting venom. In his speech, he performs a perfidious reversal of concepts, builds judgments based on paradoxes, and relativizes the perception of things. Mills loses – gets provoked. Somerset, on the contrary, remains unmoved to the end. He does not agree that the perverted extravagance of crime and the sadistic cruelty of the criminal – even if focused on rapists and sexual perverts – are considered the only right form of dialogue with humanity.

John Doe, however, does not give up, he constantly controls the course of events. His tirades about sin, guilt and punishment are a deceitfully played role of God’s chosen one; they are a theatrical spectacle, roaring with demagogic declarations, under the pressure of which it is very easy to bend; finally, they are a cynical attempt to pull a man to the “other side” – a satanic show of virtuoso manipulation of the word. In the “car” sequence, what is more important than what Doe says is how he speaks, how he uses language. It is significant that he addresses the detectives (as well as the audience) as a bit of a clown, the author of mocking “diaries”, a sarcastic chronicler of human misery. Why is he limping? Was he parodying with this gesture the disability of humanity, chasing after delusion, wallowing in the mediocrity and trash of everyday life? Or maybe he’s just pretending to be a fairground joker whose ludic instinct allows him to carelessly desecrate any sacredness? If the above statement is true, then, firstly, it refers us directly to Bakhtin’s theory of the carnival, and secondly, it is, in my opinion, the key to deciphering the meanings encoded in John Doe. Being the incarnation of all Evil, he shows inclinations characteristic of the representatives of Hell, i.e. he can combine opposites not by contrast, but by a uniform alloy, he can smoothly go from one extreme to another – from real macabre to circus buffoonery, from anointed seriousness to farcical ridiculousness. – and it does so without compromising its image. He emphasizes his advantage through laughter. In Goethe’s Faust, Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, or King’s The Man in the Black Suit, wherever you look, the same face, contorted in a grotesque grimace, the same caricatured gestures: on the one hand, a hyperbolically exaggerated mocker preparing “surprises” ” for the unsuspecting audience, on the other – as if a demon dissected from a Gothic bas-relief with eyes burning with live fire. In the moments of the highest tension, in the climactic moments, Doe is able to interrupt the conversation about the dead dog and defuse emotions with one clown: “I didn’t do it”, which in the context of his previous “accomplishments” sounds really bizarre.

The Anti-Mystery

The mysteries praised the cosmic order resulting from an unwavering faith in the wisdom of God’s decrees – in the film this trust is replaced by prolonged sobs.

The final sequence is bathed in bright daylight. It’s not a coincidence. Solar iconography played a significant role already in Fincher’s first film – Alien 3, when it set the time frame of the plot, fastening the story with a kind of bracket in the form of shots of the setting and rising sun, and heralded the coming of the night, giving the story a taste of a dark variation on the medieval allegory of grim reaper. Meanwhile, in Seven, the director resigns from showing the sun’s disk, and also spares us the view of moving clouds pierced by rays. Thanks to such a procedure, the symbolism of light loses its unambiguity and frees us from the obligation to mechanically interpret this sign in exclusively religious categories, which would be a very unfortunate move, contrary to what we had seen before. Because if we assume on the spur of the moment that God has spoken and sent John Doe to Earth to punish mankind in the same way as Yahweh once punished the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah, then the character of the antagonist would be suddenly reduced to the rank of a passive instrument, and the film itself with suspicious ease would fall into banality (every second psychopath declares that he is an extension of the punishing hand of justice). Leaving aside the issue of Doe and his function in the divine economy of salvation, the flaw in such an interpretation is most clearly determined by Tracy’s sacrifice. From the mystery perspective, the murder of her is an incomparably greater scandal than, say, the murder of a pregnant woman in a crime story. In the first case, there is an attack on the corpus of universal values, in the second – on individual human life; in the first case, symbolism, tradition, everything is lost, in the second – “only” an innocent person. This is different from the Old Testament Flood or the destruction of Sodom. It used to be said that Stat crux dum volvitur mundus (“The cross stands when the world turns over”). On the mystery scene, such a cross is undoubtedly the figure of Tracy, who until the end remains an uncompromised and indestructible figure. Of course, it can be located in a “compromising” context (the City), but then it is not the values that it represents that are subject to degradation, but the very context that was intended to annihilate it. For this reason, I cannot agree with the unintentionally divine interpretation of light symbolism in the film. The light retains its symbolic reference in Seven, but while the rain pointed directly to the “Book of Genesis”, the sun’s glare is self-sufficient, referring to the work itself, valorizing the ending as such, emphasizing its fundamental meaning against the background of the whole movie.

The last scenes demand elevation above the rest of the film, as they are the moment of the decisive confrontation between Good and Evil. It is not without reason that the thing is happening in a remote area, away from the city bustle. The desert as a space of seclusion, free from undesirable outside intervention, was perfect for the final. It is then that the director dismantles the mystery scene, breaking, one by one, the pillars supporting the ceiling of the scene. In the medieval mysteries, everything that existed in any way was turned towards God – in Seven, God withdraws from the world. The mysteries praised the cosmic order resulting from an unwavering faith in the wisdom of God’s decrees – in the film this trust is replaced by prolonged sobs. The director unfolds before us a Dantean vision of the modern infernum, pathologically distorted, devoid of metaphysical justification. In mysteries, individual spheres formed a coherent, hierarchical whole – in Fincher’s the picture is incomplete, because he lacks the view of Heaven. Accepting as credible the thesis that I put forward and concerning the identity of the earthly area with the abyss of hell, what strikes me is the futility of the mentioned quote from the Bible about the downpour, which is supposed to bring a deluge on humanity. In the Book of Genesis it stands: “For in seven days I will send rain on the earth for forty days and forty nights to destroy everything that exists on the face of the earth – whatever I have created…”. Despite the constant driving rain, the spiral of violence in the film, instead of slowing down, gains momentum, losing absolutely nothing of its senseless momentum. So it would turn out that John Doe is right – the sins of the world are indelible.

The confrontation in the desert ends tragically: Mills learns of the death of his pregnant wife and in despair kills the murderer with a shot to the head. Somerset’s warnings are in vain as he tries to convince his partner that Doe’s death equals his victory. After the execution there is silence. Significant words are then said, paraphrasing Hemingway: “The world is a good place. It’s worth fighting for”, and Somerset adds off-screen: “I agree with the other part”. As a spectator, I could safely bet on a Manichaean draw and prevent the murderer’s all-diluting relativism from triumphing. But I can not. In Seven, the predominance of crime over the world of law is too great to conclude the film with a compromise formula. This movie is not meant to cure cancer; it is to draw attention by force to the presence of evil in the world, which is tacitly allowed. Good people do nothing, so evil roams the earth with impunity. This is one of the boldest theses that American cinema has made in its long history. What’s more, the thesis is presented in an extremely original way – in the form of a detective story, which was created for completely different purposes than preaching from the pulpit. It is impossible to go further. Fincher was one of the first in mainstream cinema to have the audacity to take away all hope. Like Dante in Hell.

From the author

In Seven, the just punishment is contrasted with the victorious procession of Evil.

At the end, two questions: is the criminal mystery solved in Seven, and if so, will the social, legal, moral balance, whatever we call it, return to the state from before the crime was committed? Answering the first question: the mystery is unraveled, but without punishment – the murderer voluntarily appears at the police station and hands himself over to the police. In this sense, Seven can be safely considered a full-blooded detective story, because all the unknowns are revealed: we know who the murderer is and why he killed, in short, we know the perpetrator’s identity and motives. As for the second question, I am afraid that no – the conclusions of the investigation conducted by Somerset and Mills – if we accept my interpretation of the world as a mystery as credible – are ontological, have nothing to do with the process of restoring the socio-legal order, as is usually in the case of a criminal charade. In Seven, the just punishment is contrasted with the victorious procession of Evil: the murderer was caught (at his own request), but not defeated, he meted out the punishment, trampled the innocent, destroyed the system of values that negates him (the murderer). The motif of wrongly or rather unjustly administered punishment is particularly important in the film. Mills blindly believed that good always triumphs, and consequently this belief destroyed him. In the final act of Doe’s unimaginable cruelty against his wife, there is a cruel taunt: Mills is punished for the sin of anger, which also ends the murderer’s rhyme. Punishment comes as a reminder that no one is above sin, not even a good and noble cop arresting a murderer.

Sometimes I wonder if the original dialectic has not been reversed in Seven: Good is Evil and Evil is Good. A just society and social justice – isn’t this a specific terror that needs to be responded to with terror? No detective story aroused such anxiety and moral resistance in me as Fincher’s film. It is true that Fantômas, a criminal by inclination, created by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, when he was captured and sentenced to death, had an innocent man die under the guillotine instead; it is true that Fantômas struck again and again, with contempt for the Law, always successfully and always with impunity. The series about his fate can be considered an apotheosis of rape and crime, but in comparison with such a detective story as Seven, it will only be a local apotheosis, referring to a specific era in which the criminal acted, and aimed at a specific environment – the French bourgeoisie – without universalist aspirations. Seven, on the other hand, is a kind of film palimpsest, a work that torments the viewer with a lack of content, constantly challenging him to discover new unifying rules. In fact, every “criminal” prop appearing in the film has a symbolic potential, it can lead to the trail of hidden meanings, revealing the subcutaneous stratification of the presented situations or the perversely allusive nature of the movie. Fincher uses a double meaning all the time: characters, places and gestures have literal and figurative meanings. The presented world is given to us directly – the suggested world is concealed. So, in my opinion, Seven will be an ambiguous and enigmatically mysterious movie – a masterpiece of the genre.