It is not easy to find a concept for a film about a serial killer who was never caught, about whose case there are more uncertainties and assumptions than certainties. One cannot convey how the truth was uncovered since there is no truth. One can adopt a certain point of view, but it will necessarily be one-sided and subjective. Fortunately, David Fincher achieved the impossible by combining an objective recapitulation of the Zodiac case with the subjective conclusions of Robert Graysmith in such a way that essentially no definitive conclusion is reached; doubts remain, and at the same time, we look at the case from the inside, through the eyes of all those involved, piecing together the fragments of the puzzle and having the full opportunity to draw our own conclusions. No judgment in Fincher’s Zodiac is categorical; none is final. There is enough space for our own speculations, as the entire reconstruction of the case is accurate, factually faithful, without a preconceived thesis dictating the terms. Robert Graysmith has his thesis, and we can have ours, and the film allows for that completely.

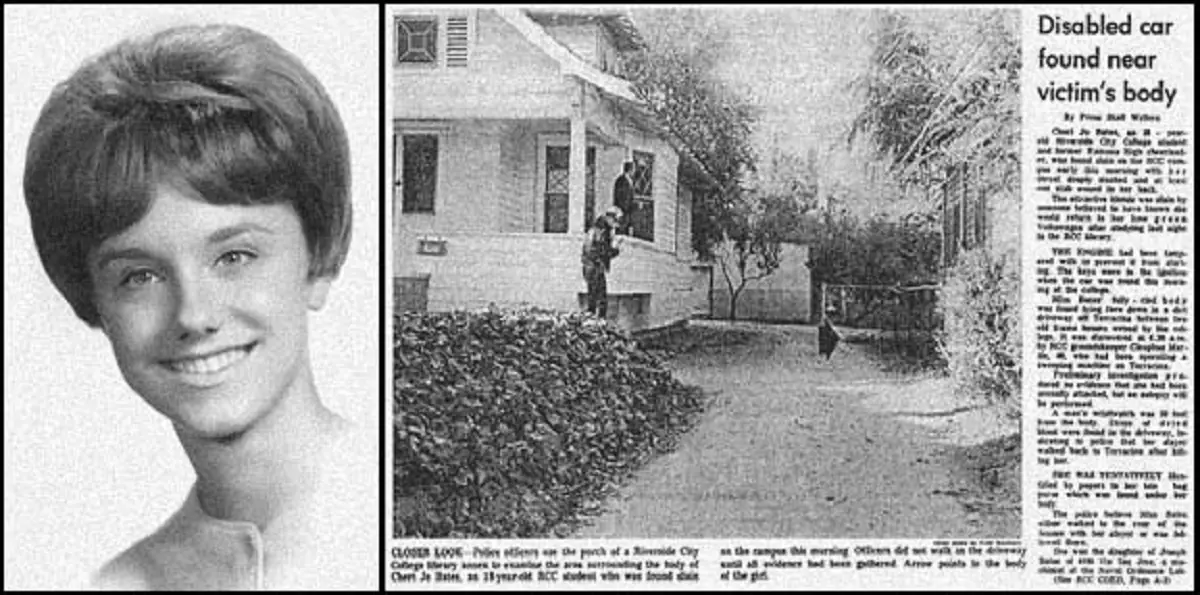

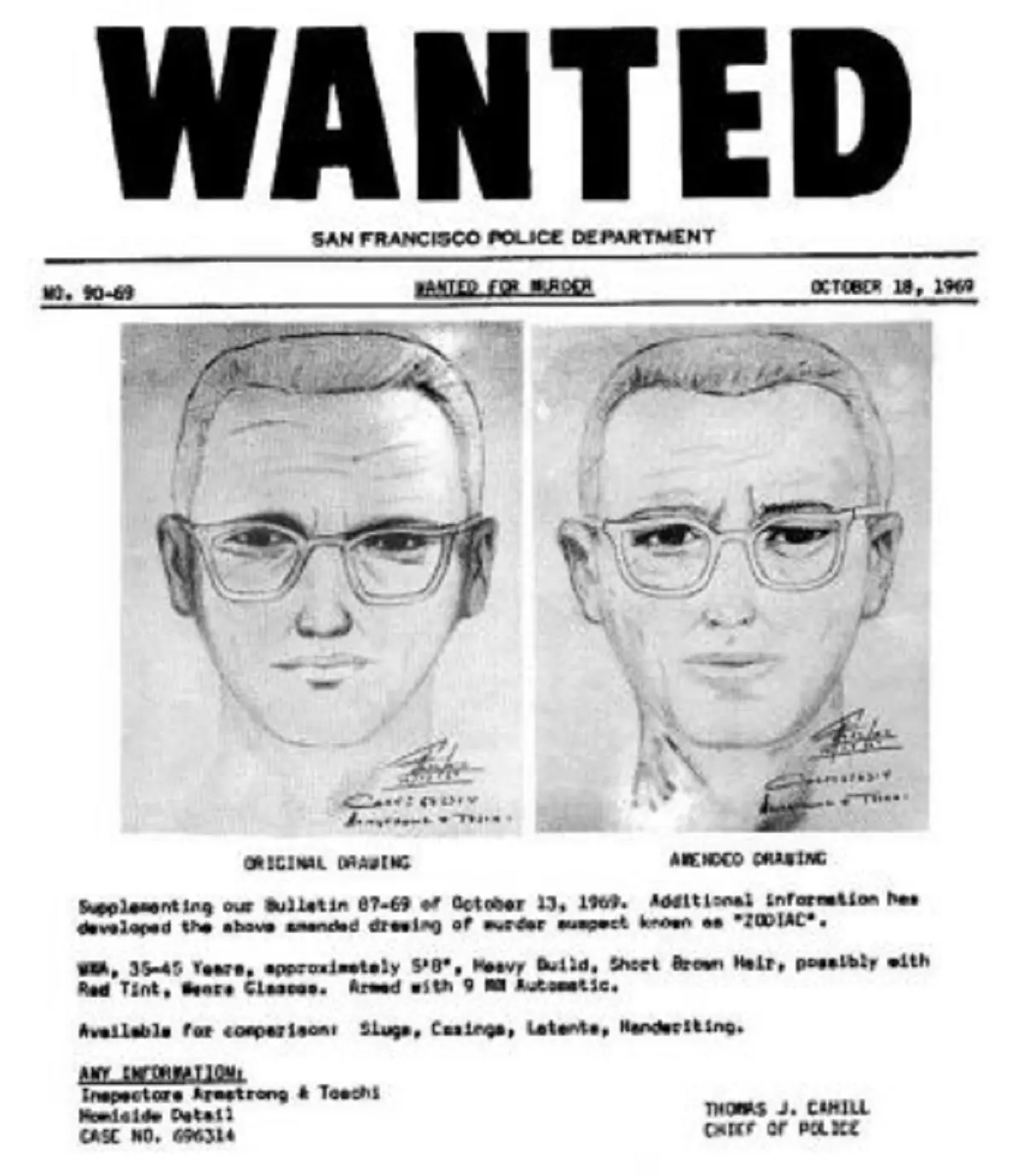

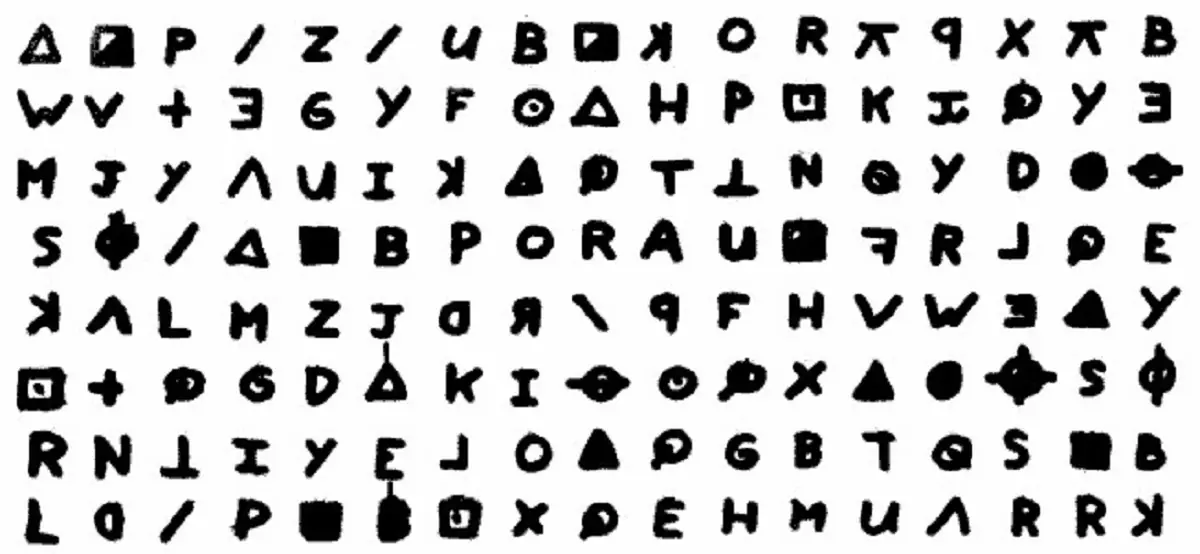

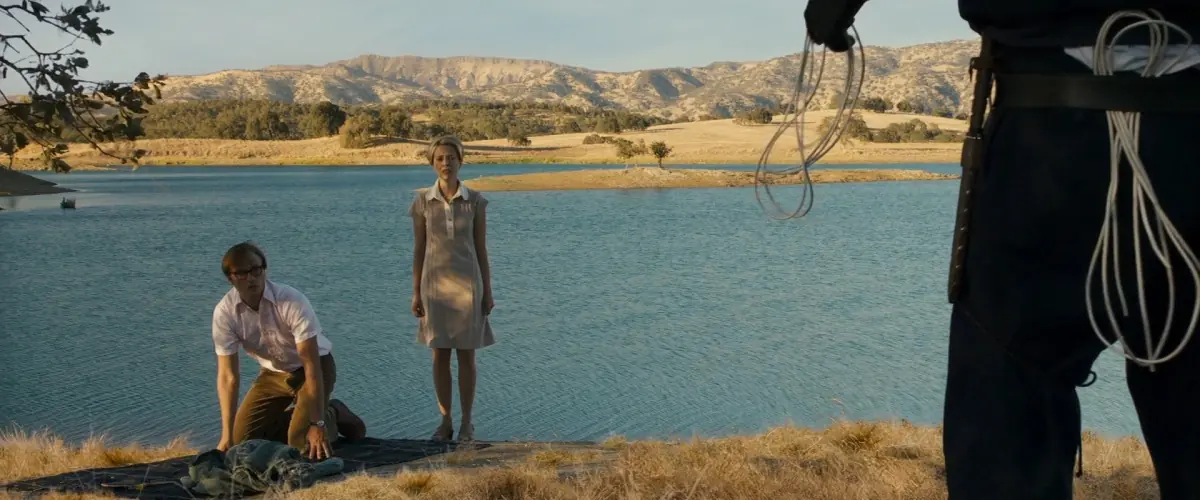

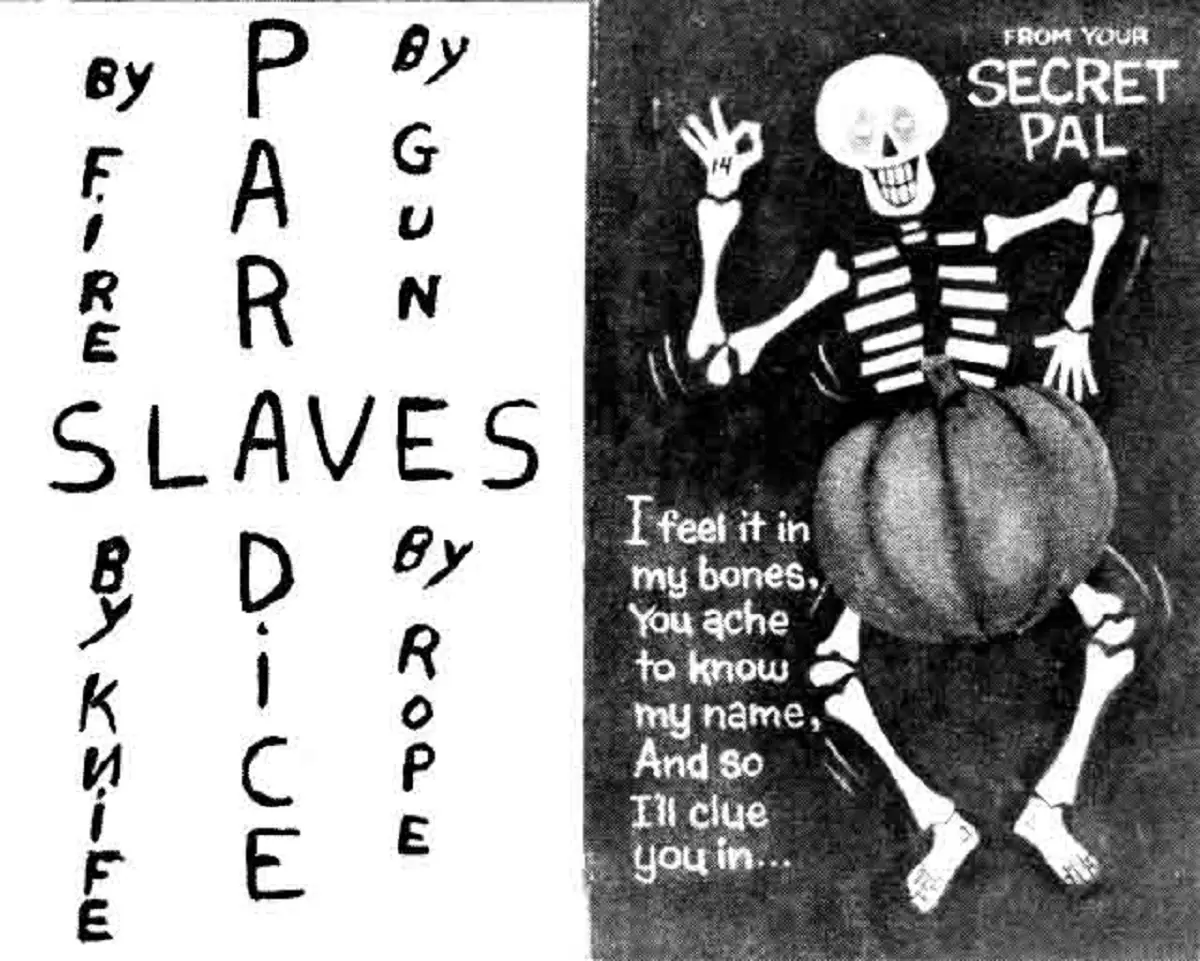

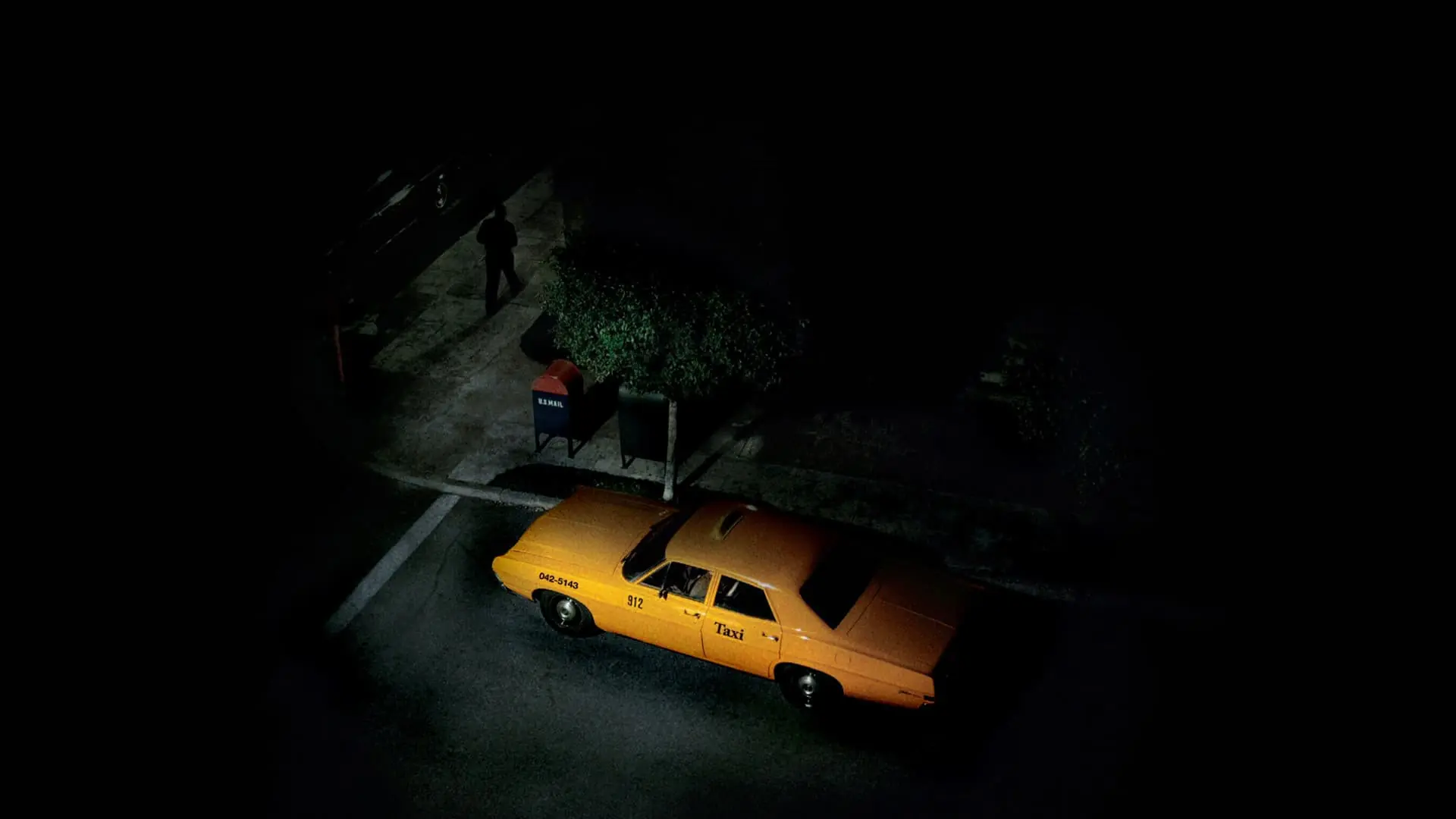

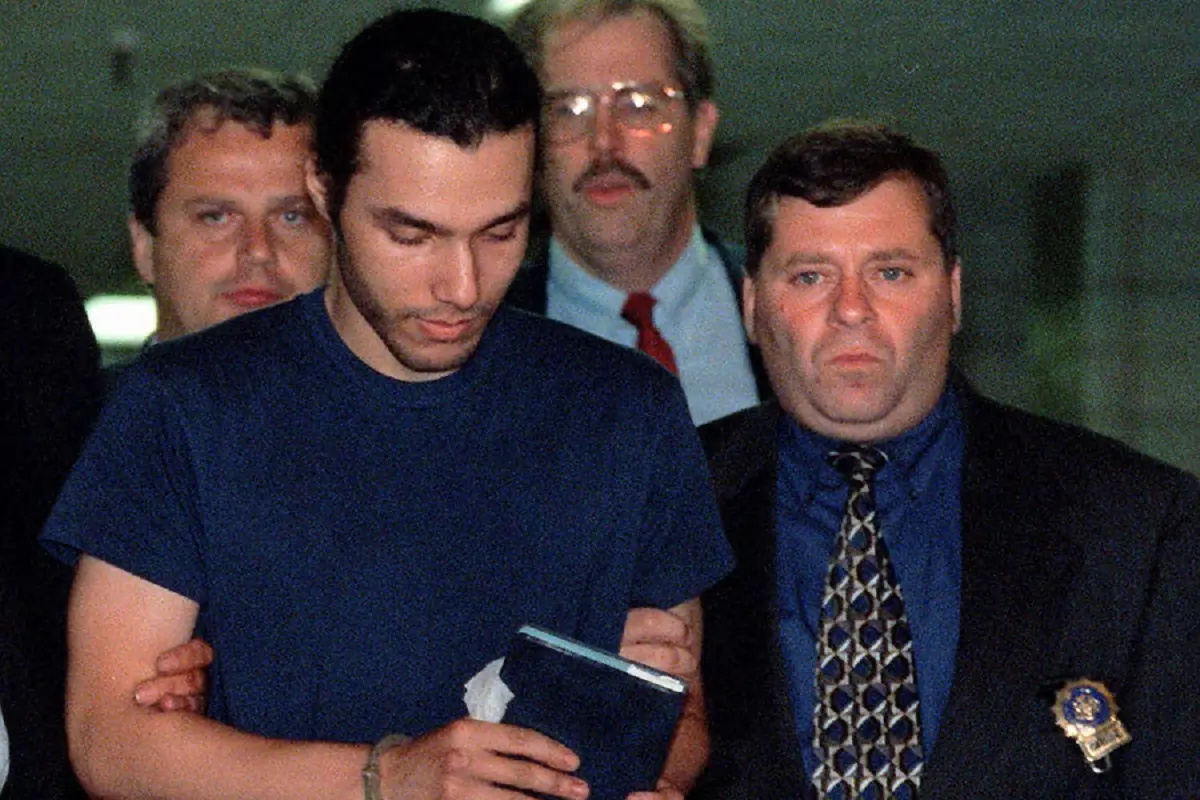

The atmosphere of Zodiac is extraordinary. Thick, dark, it pulls you in from the first minute and doesn’t let go for a moment. We navigate through the meanders of a complicated investigation, witnessing how the fascination of an outside observer develops, throwing themselves headfirst into dangerous speculations—how accurate those are is an entirely different matter. Graysmith’s conclusions, presented in his bestselling book Zodiac, did not receive widespread acclaim, although he is still regarded as one of the best specialists on the case. In Fincher’s Zodiac, the central focus is on the people—painstakingly sifting through evidence, disheartened in the face of failure, excited by every new lead, juxtaposing their experience, commitment, and dedication against the undeniable skill of a cunning killer. We see the investigation from its unappealing, bureaucratic side—piles of paperwork, miles of dubious witness testimony, a procession of witnesses seeking their moment of fame, formal obstacles, regulations, and paragraphs, all while amidst it all is a sudden glimmer of light in the darkness that we cling to desperately, although it may lead nowhere.

The figure of Robert Graysmith serves as the glue for Fincher, a guiding motif upon which he built the structure of his film, but without pressure, without suggesting that this version is the only correct one. It is merely an axis around which he oriented the best recapitulation of the Zodiac case that cinema has known so far. He abandoned cheap sensationalism, focusing instead on the people—those whom the Zodiac case affected personally, in various dimensions, with varying effects. We cannot look from the perspective of the perpetrator since we do not know him. Thus, the only option is to view things through the eyes of the people who knew him as well as possible. Add to that facts, testimonies, speculations—and the entire picture slowly shapes itself right before our eyes, creating an absolutely fascinating, engaging story. Without excessive dramatization, moreover, this is not the only case, nor is it the only one that remains unsolved. It is not the center of the world but merely one of its elements.

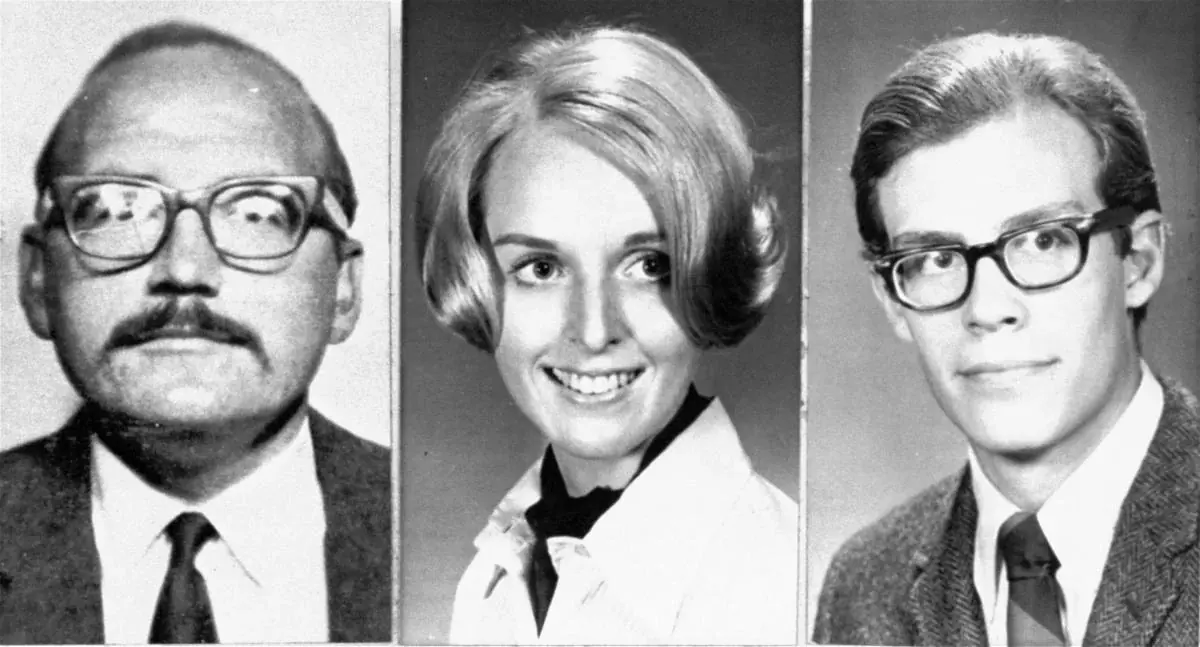

Fincher’s film is closer to All the President’s Men than to The Silence of the Lambs. The axis is the investigation, which, in the case of the Zodiac, is multi-faceted, multi-dimensional, and unfolds in several locations simultaneously. The story runs along multiple tracks, on one side through the media channel and on the other through the police. There are long-standing misunderstandings between law enforcement and sensationalist media, but the rhythm of the Zodiac’s actions inevitably forces cooperation between the two sides. Various individuals enter the orbit of the investigation and then, just as suddenly, disappear—relatives of the victims, police officers from other districts, witnesses, attorney Melvin Belli, families involved in the case. A powerful network of interactions is created, an uncontrollable flow of information, making it increasingly difficult to separate the wheat from the chaff, facts from media creation, and on this fertile ground, the Zodiac is born—a symbol, the Zodiac—an autonomous phenomenon. A phenomenon that persists while Robert Graysmith’s children grow up, Toschi’s partner changes career paths, Paul Avery resigns from his job, and Sherwood Morrill retires…—in this three-hour film, a significant slice of many people’s lives is condensed. This enhances our awareness of how complicated and absorbing the Zodiac case was, how strong its impact was, and how frustrating the lack of a conclusive outcome felt.

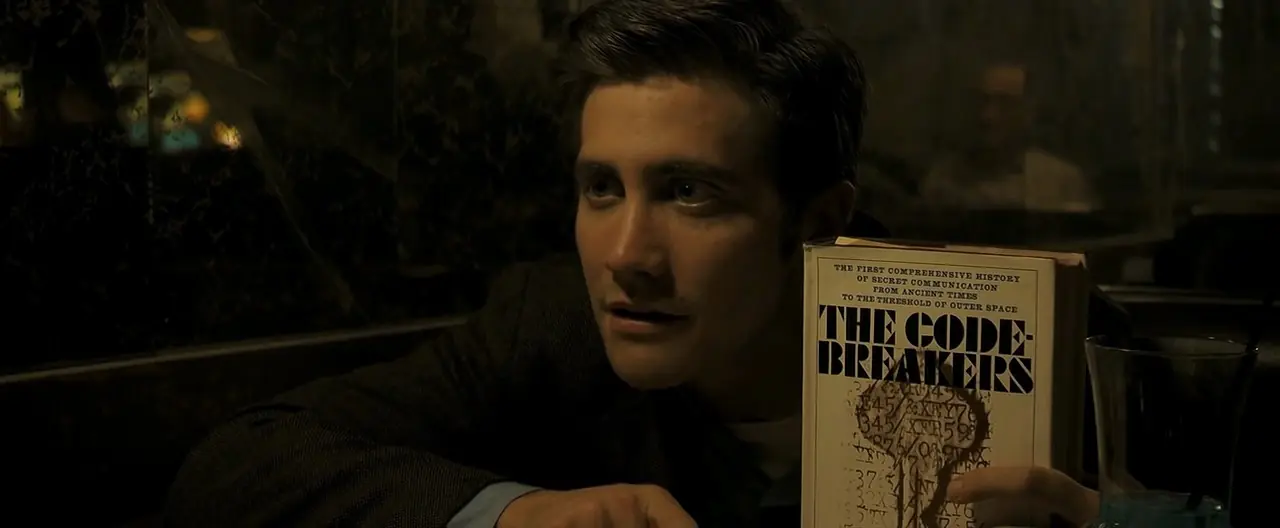

The strength of the film is firmly based on three points of a triangle, three outstanding acting personalities, through which the main currents of the film flow smoothly before our eyes, without chaos or disruption. There’s the strong and charismatic cop with a biting sense of humor—David Toschi (Mark Ruffalo)—our guide through the realm of the police investigation. Paul Avery (the brilliant Robert Downey Jr.)—the eccentric reporter—serves as the audience’s ticket into the arena of media frenzy, a partially unhealthy but certainly intense excitement that burns out anyone unable to withstand the pressure. Finally, there’s Robert Graysmith (in a calm and measured performance by Jake Gyllenhaal)—the observer, commentator, and someone entirely on the outside who, paradoxically, turns out to be the one whose life is most profoundly impacted by the Zodiac. Three points of view, three interested parties, three elements of the overall puzzle—a pattern that never fully materialized.

As the Zodiac desired, a good film has been made about him. Although he probably wouldn’t be satisfied with it, as he is not the main character in the film about himself. For the outside observer, the Zodiac is, fortunately, not a biography but a documentary of the times, a testimony to a real case and its implications—the impact that is rarely considered while following dry press reports. It is a historical gem that is excellent to watch. On the shoulders of the most mysterious serial killer since Jack the Ripper has grown Fincher’s most mature film to date. I wonder what the Zodiac would think of it?