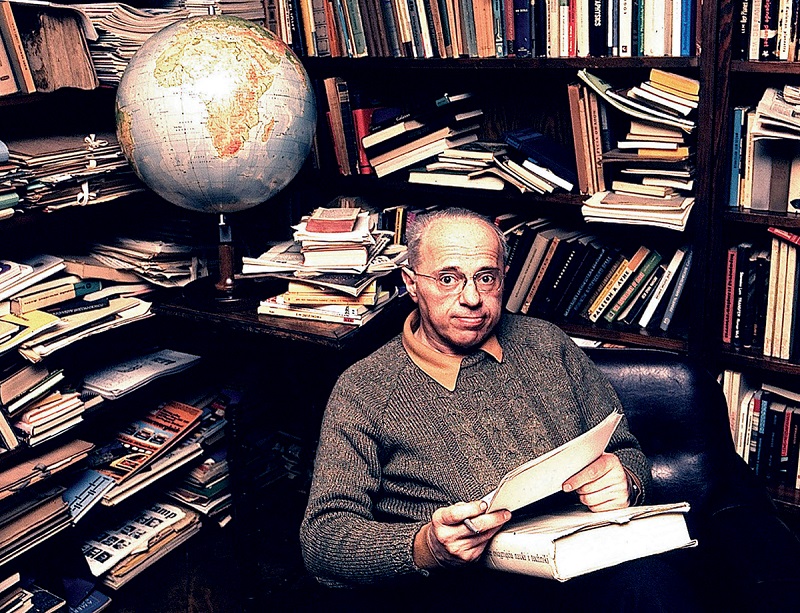

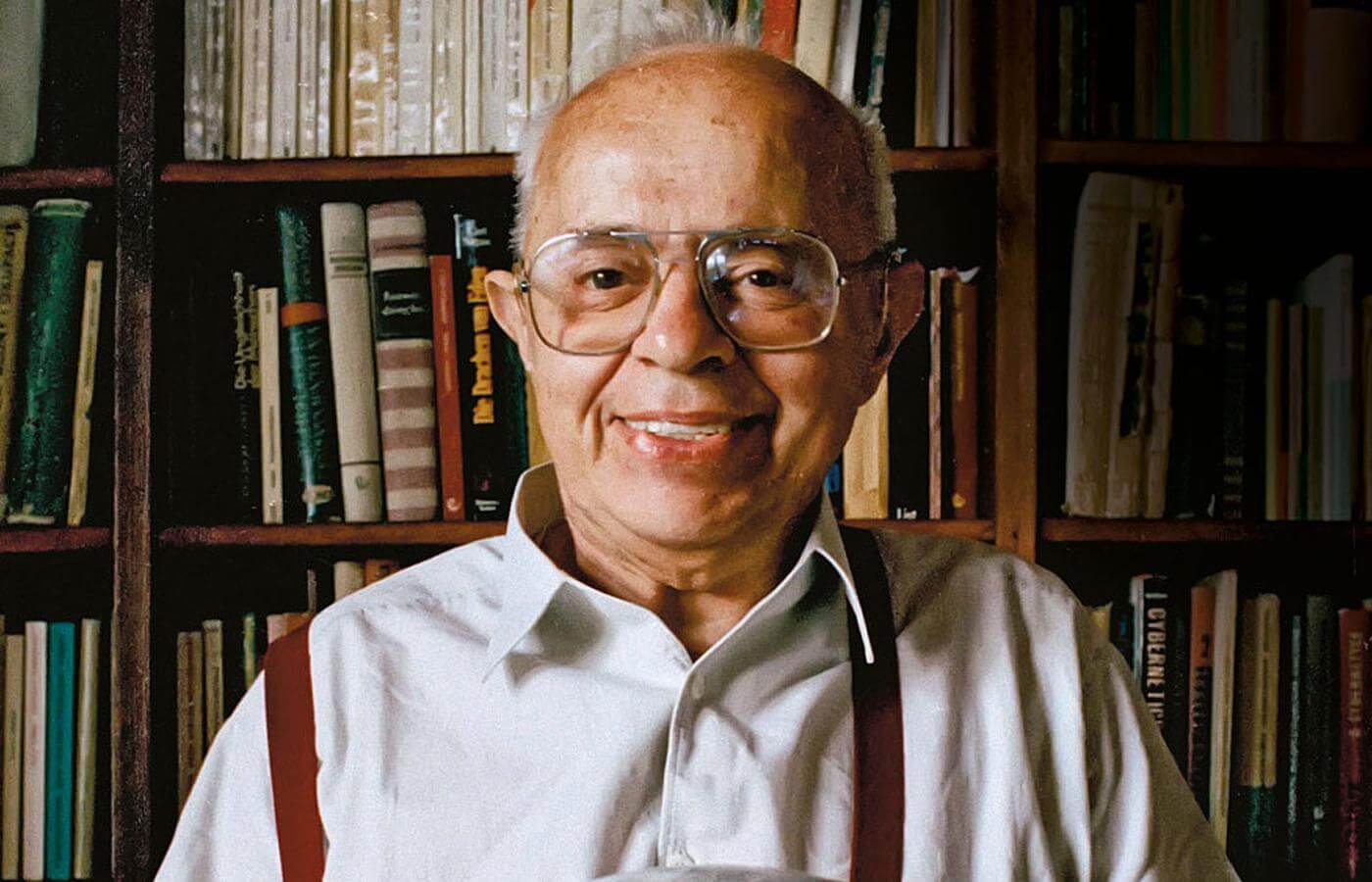

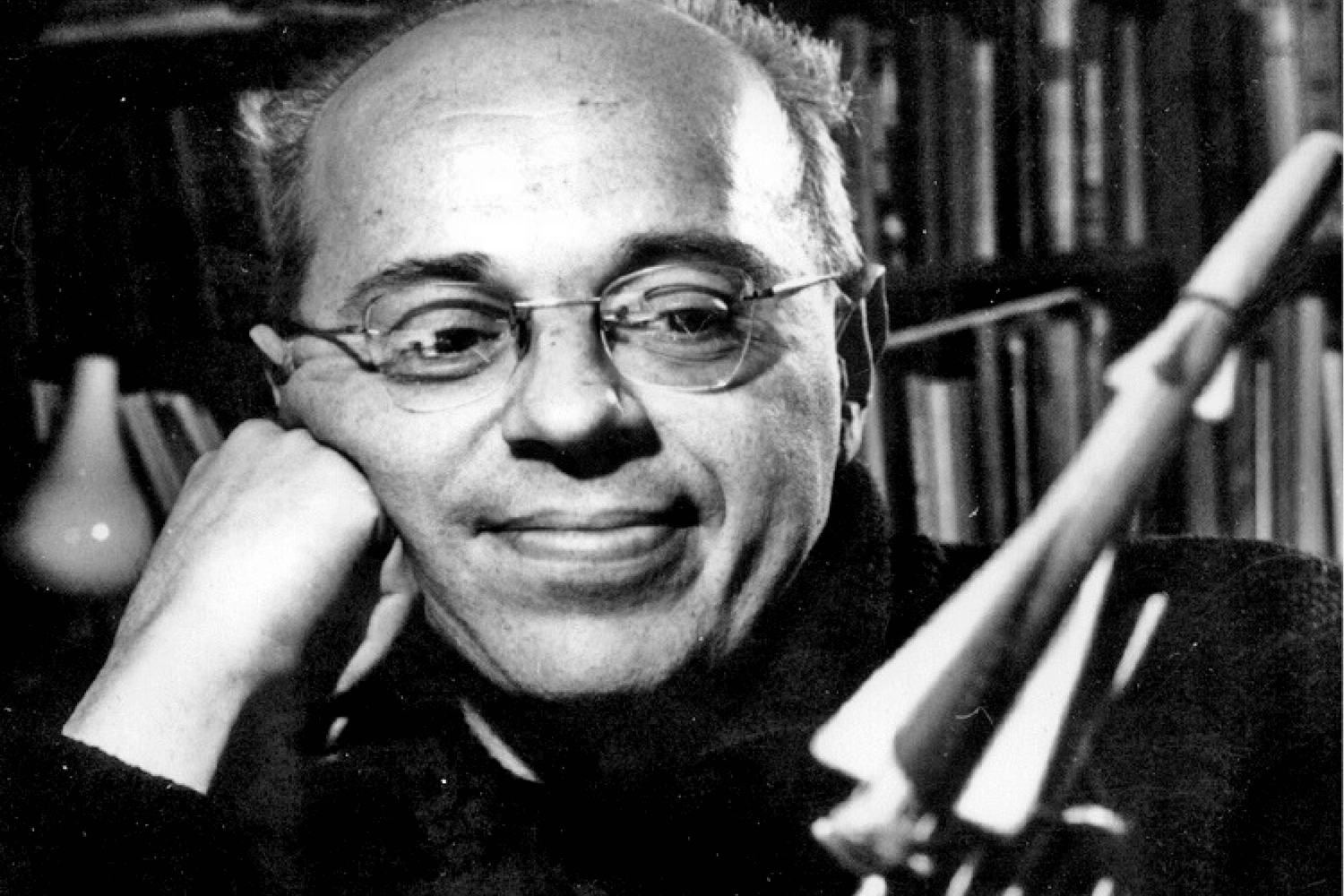

Screen adaptations of STANISLAW LEM, a science fiction GENIUS

Stanislaw Lem was born on September 12, 1921 in Lviv. There, in 1944, he began medical studies, which he completed four years later in Krakow. His literary work, initiated with poems and stories about the occupation, almost simultaneously moved into the realm of science fiction. In 1946, Lem writes his first science-fiction story Alien and the novel Man from Mars. In 1951, he made his debut on the publishing market with the SF novel Astronauts. In 1954, his next novel The Magellanic Cloud is published. Over the next 15 years, Stanislaw Lem consolidates his position as the best Polish science fiction writer and one of the world’s most outstanding SF writers, although each time he firmly emphasizes how much he dislikes science fiction, crushingly criticizing most of the genre’s ideas.

Lem’s name was widely known in Poland and abroad in the 1950s. The writer celebrated his triumphs with the adventures of Ijon Tichy in The Star Diaries, he also had The Magellanic Cloud and Eden under his belt, and Return from the Stars and Solaris were to see the light of day in a few years. Meanwhile, the poor cinematographies of the socialist countries, rising from the ashes of the war, timidly began attempts to make their own science fiction films, unlike the dynamically developing post-war sci-fi cinema in the United States. Several films exploiting the most classic SF literature motifs were made in the Soviet Union as early as the 1950s. The cinematographies of the remaining Eastern countries began flirting with science fiction only from the next decade. Brotherly artists from Poland and the East Germany were among the first to attempt such an endeavour. The script material for this prestigious co-production was the first published SF novel by Stanisław Lem, Astronauts from 1951.

Related:

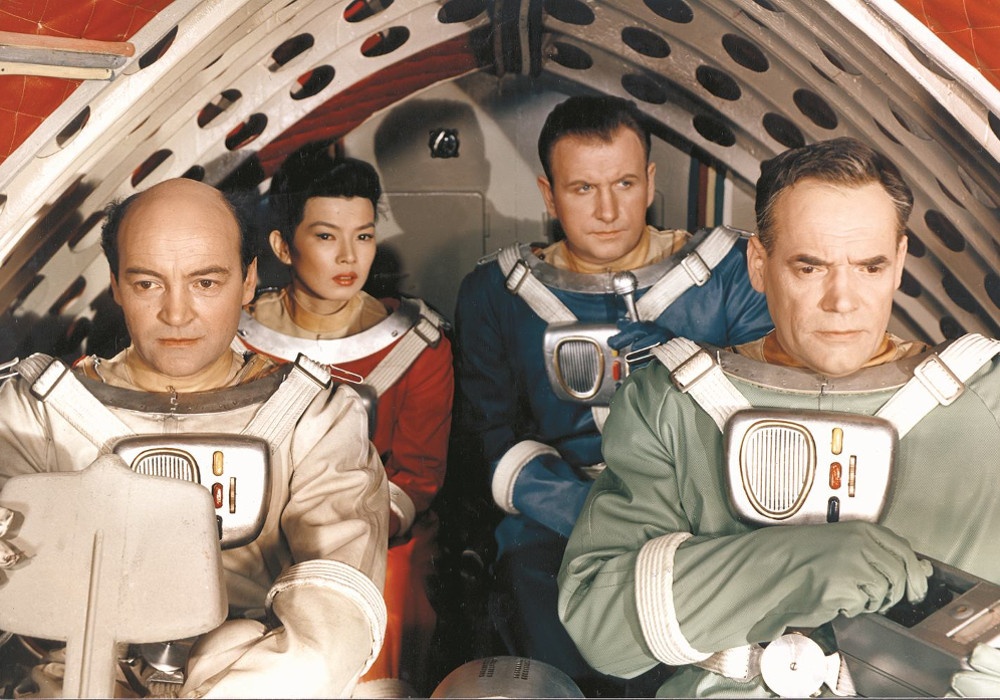

The Silent Star (1960)

The year 1970. A piece of metal, completely unknown to mankind, was found in Siberia, which was the remains of the Tunguska meteorite from 1908. Scientists, after calculating the supposed trajectory of the meteorite’s flight, came to the conclusion that the piece of metal is the remains of a spacecraft from Venus that crashed on our planet. Earthlings, under the enlightened leadership of socialist countries, decide on the first interplanetary manned flight to Venus. Expecting to see an advanced, thriving Venusian civilization beneath the cloud cover, the crew of the spacecraft Kosmokrator saw the blackening, radioactive ashes of Venusian technology reduced to rubble. The conclusion: the inhabitants of Venus planned an invasion of Earth, but they used the carefully collected arsenal to kill each other…

“Thank God no one remembers this film anymore. The Silent Star was a terrible mess, gibberish socialist realist pie. For me, it’s a very sad experience. The only benefit of making this tragedy was the opportunity to see the western side of Berlin. The wall dividing Berlin in two didn’t exist yet, so in the intervals between constant brawling with the director, I would sneak out to the west side.” (*) – as you can see, Lem does not mince words when describing attempts to adapt his work to the screen, although on the other hand he himself sold the rights to the screen to people who should rather not do it. The leading Eastern Germany director of those years, Kurt Maetzig, presented a quality directly proportional to the achievements of the cinematography of this country created artificially after World War II. Instead of guiding the actors properly, Maetzig placed figures in front of the camera, made of nothing but lofty ideas, poured with a thick, unswallowable, morality play sauce. The characters on screen are devoid of life and energy, not to mention wit or auto irony. The effect of such direction (or rather lack of it) is the viewer’s complete indifference to whether our heroes will return unharmed from Venus or not.

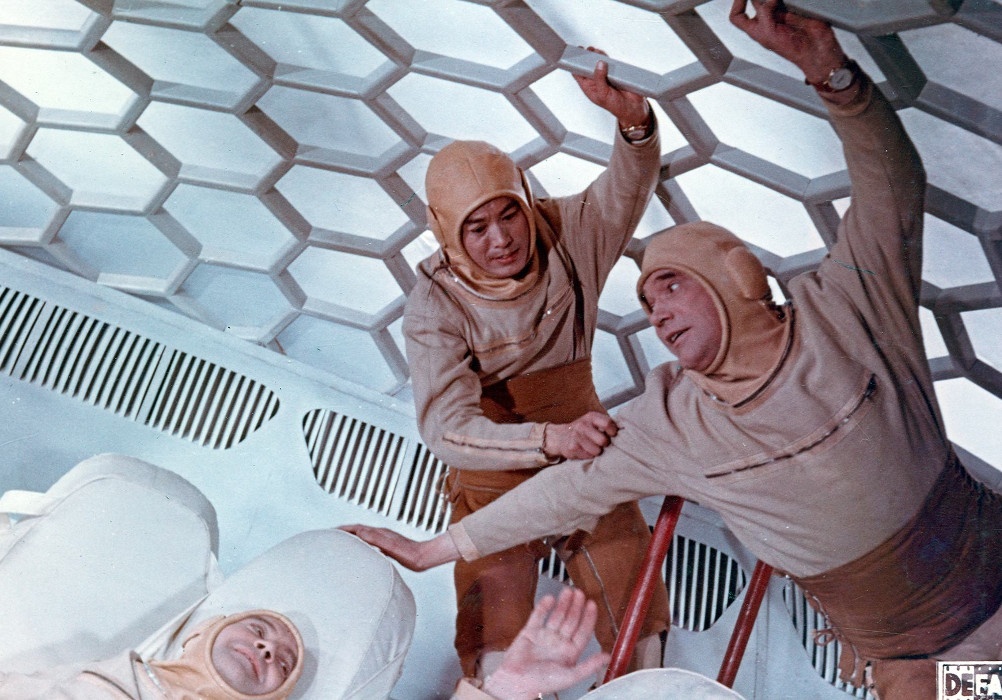

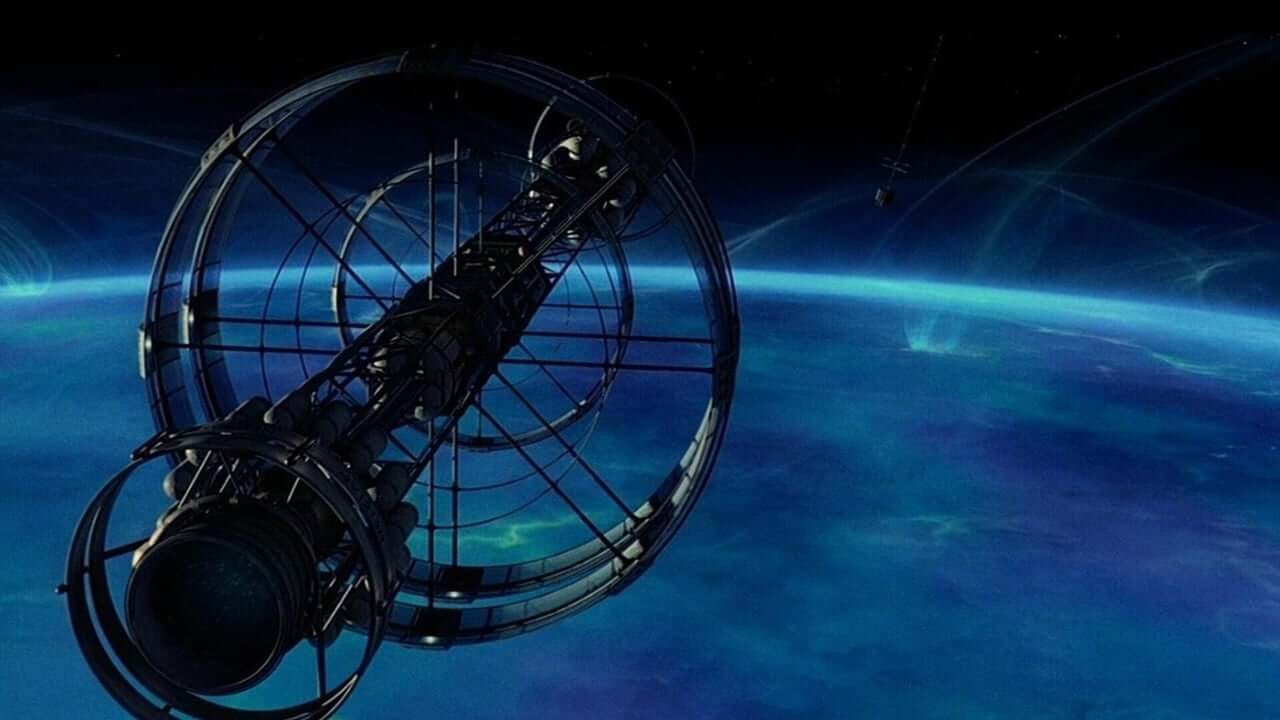

The visual side of the film is the true museum of SF imagination. For the modern viewer, the view of the interior of the Kosmokrator is so lame that it’s just simply laughable. The ship’s electron brain, called the Marax, can perform a staggering 5 million operations per second. On-board devices are mandatory sets of flashing lights or screens displaying abstract patterns. But it should be remembered that The Silent Star was actually a precursor SF spectacle in cinematographies form behind the Iron Curtain. From the time perspective, it must be clearly said that the vision of the great Polish set designer Anatol Radzinowicz (and the German Alfred Hirschmeier) must have made an impression, and not a small one. Venusian landscapes, bizarre constructions covering the surface of a destroyed planet, were an outstanding achievement for those times, as was the case with the interiors of the Kosmokrator. Nobody has such an idea about the scenery for a SF movie anymore, but space fantasy had to mature thanks to such attempts of screen artists from the past. The special effects in The Silent Star were quite advanced for those years (and technical possibilities). The optical combination of miniature photos with live action was done flawlessly, only the very use of miniature spaceport decorations screams naivety and lack of credibility. Several American critics even wrote that The Silent Star is the best-looking space sci-fi movie of its time, produced outside of Hollywood.

Ikaria XB 1 (1963)

In the early 1960s, Stanislaw Lem wrote the screenplays for two animated shorts by Krzysztof Debowski, The Trip Into Space (1961) and Desolate Planet (1962). A year later, Czechoslovak director Jindrich Polák presented the excellent, wide-screen SF film Ikaria XB 1. Under this mysterious title there is a story about the crew of a long-range spaceship traveling to settle on a suitable planet. During the journey, the expedition finds the wreck of an alien ship, but this is not the end of many unexpected and terrifying events…

For every SF lover, the above summary as vividly resembles the plots of Star Trek movies and series, and also Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979). However, we are dealing with a film made much earlier on eastern side of the Iron Curtain. And what is the connection of this film with Lem? Well, Czechoslovaks did not deign to mention it in the opening credits, but the script was based on The Magellanic Cloud, the second published novel by Stanisław Lem (published, because the novel Man from Mars was published in a book only in 1994; the first Lem’s novel was The Astronauts, The Magellanic Cloud was therefore his second).

Jindrich Polák’s film can be considered a precursor to American productions dealing with the subject of settlement space missions (not counting Fred MacLeod Wilcox’s spectacular Forbidden Planet from 1956). However, this is not a typical space opera. Instead of space heroes like Captain Kirk, we just see ordinary people with their everyday lives. Andrzej Kolodynski, in his book Heritage of the Imagination. The History of Science-Fiction Film, wrote: “probably for the first time in an SF cinema, people wash themselves, organize parties, think about spending their free time. (…) The film presents the process of psychological interaction consisting in the transformation of individual reactions into collective ones. After four months of travel, people show signs of weariness, fear of cosmic emptiness, and the dramatic conflict concerns the ways of overcoming them. Technology recedes into the background, people turn out to be the most important. The example of the Ikaria XB 1 shows the difference in the approach to the seemingly unambiguous topic of space flight. A creator from overseas would cut such material into a decent cosmic horror, or a battle spectacle, calculated for the effect. For Stanislaw Lem, classic sci-fi motifs were only a pretext for an in-depth description of a man struggle that only science fiction was capable of credibly depicting.

As you can see, the first cinematic adaptations did not put Lem in a positive mood. The Silent Star was, according to him, a complete bottom, and the Czechs did not even stutter about the plot from The Magellanic Cloud. The situation was quite the opposite in the reading world, which praised Lem to the skies for his subsequent novels Return from the Stars (1961), Solaris (1961), Diary Found in a Bathtub (1961), Invincible (1964), or collections of short stories The Star Diaries (1957) and Fables of Robots (1964). In the latter two, Lem made himself known as an incomparable mocker of classic SF motifs, a buffoon bursting with brilliant linguistic erudition who, in the form of grotesque, almost childish parables, was able to effectively smuggle extremely important issues. In The Star Diaries this wonderfully light tone undergoes a significant transformation along with the stories ending this collection of Ijon Tichy’s cosmic adventures, bearing the common title From the memories of Ijon Tichy. This is where almost revolutionary problems for the entire SF come to the fore, related to the morally questionable applications of advanced technology. It is enough to mention that the first story (unofficially called Professor Corcoran’s chests) can be successfully considered as the prototype of the fictional assumptions of the Wachowski’ Matrix.

Professor Zazul (1965) and A Friend (1965)

In 1965, two young artists, Marek Nowicki and Jerzy Stawicki, made two intimate, short films based on Lem’s prose for Polish Television. The first of them was Professor Zazul based on the third story From the memories of Ijon Tichy. The 22-minute film, shot in the vicinity of Wroclaw, is its fairly faithful adaptation. Ijon Tichy visits the titular prof. Zazul in his secluded estate. During the visit, Tichy notices a human corpse hanging from the ceiling. It turns out that Prof. Zazul was doing cloning research. Research, completed in the most unexpected way, also for Tichy himself…

The second film, made jointly by Marek Nowicki and Jerzy Stawicki, was the 18-minute A Friend, based on a short story with the same title. The plot is about a small, unimportant man named Harden, who finds a powerful electronic brain in the city’s underground, obsessed with the desire to rule the world (today we would say a supercomputer, or Skynet). The machine increasingly corners Harden, who, in a feverish hurry, expands it. The finale of the story is probably a pioneer in the entire history of scifi, a description of the connection between the computer and the human brain, through a simple cable stuck in the back of Harden’s head. Lem almost 40 years earlier passionately described practically the same thing as Matrix, and the final fight from The Matrix Revolutions looks like a sugared-up, fictionalized version of the abstract, mad mental confrontation of Harden’s brain with inhuman intelligence. So much for the story. Unfortunately, I have not seen the film itself.

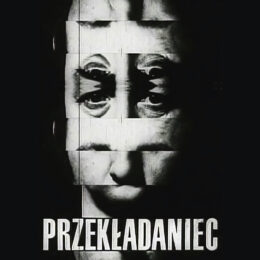

Layer-cake (1968)

The transfer of film adaptations of Lem’s works to television screens was unexpectedly supported by Andrzej Wajda himself. The Master decided to rest after the hardships associated with the production of the outstanding film Everything for Sale, making a 35-minute Layer-Cake for Polish TV. The screenplay was written by Lem himself, based on his own short story Do you exist, Mr. Jones?. The theme of this comedy revolves around the then fantastic issue of transplantology. Rally driver Richard Fox, being successful on racetracks, again and again suffers from very dangerous accidents. From each of them, he eventually comes out alive and well, thanks to the brilliant Dr. Burton, who replaces the damaged body parts of the driver with natural organs left over from the fatal victims of his collision. In other words, Fox’s vitality is conditioned by the number of spectators unintentionally killed by him on the track, which is most strongly reflected in the driver’s psyche, taking over the features of his donors’ prototypes. This is where the typical Lemian problem begins, related to the inability to determine how much Fox is still in Fox and whether Fox is no longer the combination of all the people whose organs he carries inside himself, rather than a sovereign individual.

The story was about the process of cyborgization (difficult word!). The literary Mr. Jones has to successively replace his body parts and organs with artificial ones, which leads to an extremely interesting question, when does a man end and a machine begin. In Wajda’s film, progressing cyborgization has been replaced by a transplant (an even more difficult word!) spiral with no end in sight. The whole thing looks great, the humor is great, the decorations perfectly match the future entourage, and the whole film is done with a tongue firmly in cheek. The lamented Bogumił Kobiela in the role of Fox is in his element. Only the racing sequences themselves look quite chaotic. Layer-cake is the only film according to Lem about which the author himself speaks flatteringly, probably because he took special care of the whole thing, being the author of the script.

Solaris (1970)

Contact with an extraterrestrial form of intelligence has been pumped up in science fiction literature and film since Wells’ The War of the Worlds (1898). There were many variants – a massive invasion of Martians, a man as an unconscious aggressor on the indigenous alien planet, a single form of extraterrestrial life that knocks out a group of people cut off from the world, an impossible contact that leaves both sides in the positions of observers, and finally the peaceful aspect of a close encounter. Lem invented something much more crazy – a thinking ocean inaccessible to rational cognition, capable of penetrating the minds of human observers and creating thinking and feeling replicas of people, drawn from the recesses of the human brain. Written in 1961, the novel Solaris is still considered Stanisław Lem’s most outstanding fiction achievement, ranked among the world’s top achievements of science fiction literature of all time.

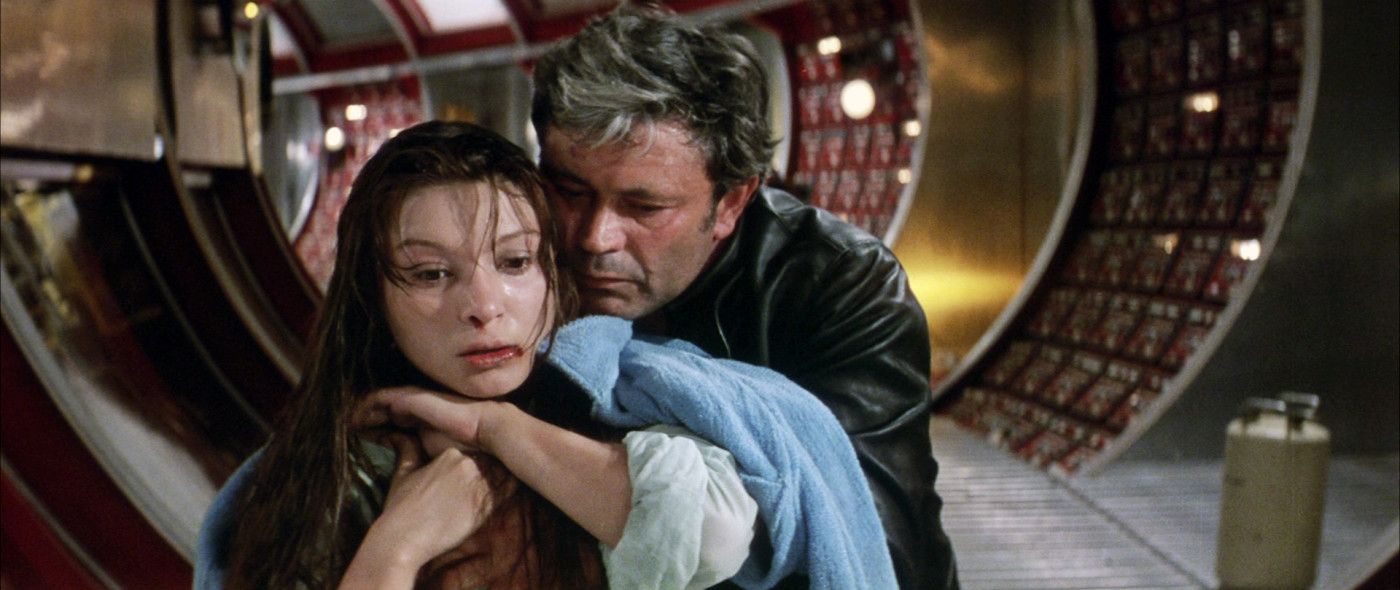

In 1970, the first adaptation of Solaris was made in the Soviet Union. It was a two-part TV movie directed by Nikolai Nirenburg. Two years later, one of the greatest Russian directors, Andrei Tarkovsky, presented his own version of Solaris. Kris Kelvin arrives at a research station suspended above the surface of the planet Solaris to unravel the mystery of the inexplicable behavior of three members of the station’s crew. On the spot, it turns out that Gibarian committed suicide under inexplicable circumstances, and Sartorius and Snaut hide their own suspicions about the ocean covering Solaris. Kelvin sees people in the station who shouldn’t be there. The tense situation reaches its climax with the arrival of Harey, Kelvin’s wife who died by suicide and has no idea where she came from…

Lem’s favorite tidbit about Solaris is that when he started writing it, he had no idea why Kelvin had come to Solaris. Brilliant ideas were born in the process. Possessing an unquestionably divine thinking ocean power, it was able to create living and sentient replicas of humans that projected the memories of the station’s crew members. Lem was equally interested in the issues of contact, typical of science fiction, as well as in the fascinating analysis of the human understanding of the world, burdened with human weaknesses, in the face of the incomprehensible driving force of cosmic intelligence. The contact itself seems to be impossible to achieve on the level of understanding, because the border separating man from the ocean is impassable for both sides. Paradoxically, Solaris can penetrate the deepest recesses of the human psyche, and even perform an act of creation that is painful for people, but even a symbolic handshake is out of the question. For Kelvin, there is only observation, leading from the Solarian waves to the inside of his own soul. And this is what interested Andrei Tarkovsky.

The anecdote about Lem ruthlessly blaspheming Tarkovsky on the set of the film has already become a legend. The Master really tried to save the filming of his work at the source. What pissed pissed him off, for example was an extended earthly prologue that added Kelvin’s entire family, but seeing Tarkovsky’s steadfast artistic consistency, he capitulated and returned to his home country. Lem’s reluctance to any attempts that would violate the structural coherence and intellectual foundation of his own works made itself felt. And Tarkovsky treated Solaris in his own way. He was not interested in the cognitive aspects, he didn’t care about all science fiction with alien planets and unknown life forms. The Russian artist’s attention was drawn to a journey into the depths of man, his reactions to threats drawn directly from the subconscious, futile attempts to rationally classify seemingly impossible phenomena, and finally a tense internal struggle with completely real demons of the past. No other species could have placed at Tarkovsky’s hand such possibilities of vivisection of the human psyche. Science fiction has validated the fantastic premise of living replicas of people who shouldn’t be in this time and place. Despite significant departures from Lem, the film Solaris is a completely unique work in the history of the genre, thanks to the fact that the plot accents are shifted towards the inner cosmos of the characters.

Despite the position typical of a European artist, regarding the lack of subordination of the content to the SF costume in terms of decorations and special effects, Andrei Tarkovsky took care of the excellent visual setting of Solaris, and it is not about assessing the set design in terms of the lack of strong SF traditions in Russian cinematography. The film simply looks great, even tens of years after its premiere. What is extremely difficult for the modern viewer is its pace. Tarkowski’s Solaris is the true test of physical endurance, formally not deviating from the rest of his filmography. The director liked the extremely slow, almost static narrative, which makes 2001: A Space Odyssey look like a dynamic action movie. Celebrated transfocations, panoramas and camera moves, the weary face of Donatas Banionis, who plays Kelvin, long moments of silence and, above all, probably the most boring sequence in the history of cinema, i.e. a five-minute drive of the camera on the highway, shot in Osaka, Japan, put the viewer to a unique test. However, it is impossible not to admire the charming beauty of Vadim Vusov’s cinematography, especially in the earth sequences.

In the year of its premiere, Solaris won the main prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Although it is Tarkovsky’s most famous film in the world, the director himself considered it his worst work. The aforementioned sequence on the highway supposedly owes its senseless length to the fact that Tarkovsky wanted to justify the team’s trip to Japan in this way, which was quite a feat in those days in the Soviet Union…

Pilot Pirx's Inquest

Lem’s cosmos evolved according to the rules of the species. After the novels dealing with the great expeditions of single crews to unexplored planets, the time has come for Tales of Pirx the pilot. Here, the vicinity of the Solar System was treated as a road between Warsaw and Berlin. Outer space has become an area of ordinary work for people for whom the launch of a rocket was as common as the ringing of a telephone. The place of the heroes of the vacuum was taken by the jobbing pilots, for whom the view of the Earth from the orbit became habitual. Lem made his most popular hero, Pirx, just such a space professional. Within 9 years, Lem wrote 10 short stories (which were first published in their entirety in 1968), in which he traced the entire professional life of his protagonist. We meet Pirx as a fledgling cadet (Test), and in the final story Ananke, we see him as a seasoned commander. The series Tales of Pirx the pilot is a fascinating set of Pirx’s meetings with surprising aspects of the development of technical civilization, whose products in extraterrestrial conditions put Pirx against challenges that are rather unpredictable in his environment. An environment familiar with technology, dependent on it and treating it as something seemingly known inside out. Pirx comes out unscathed from every oppression, thanks to his cunning, intelligence, unconventional, difficult decisions, and sometimes ordinary human helplessness.

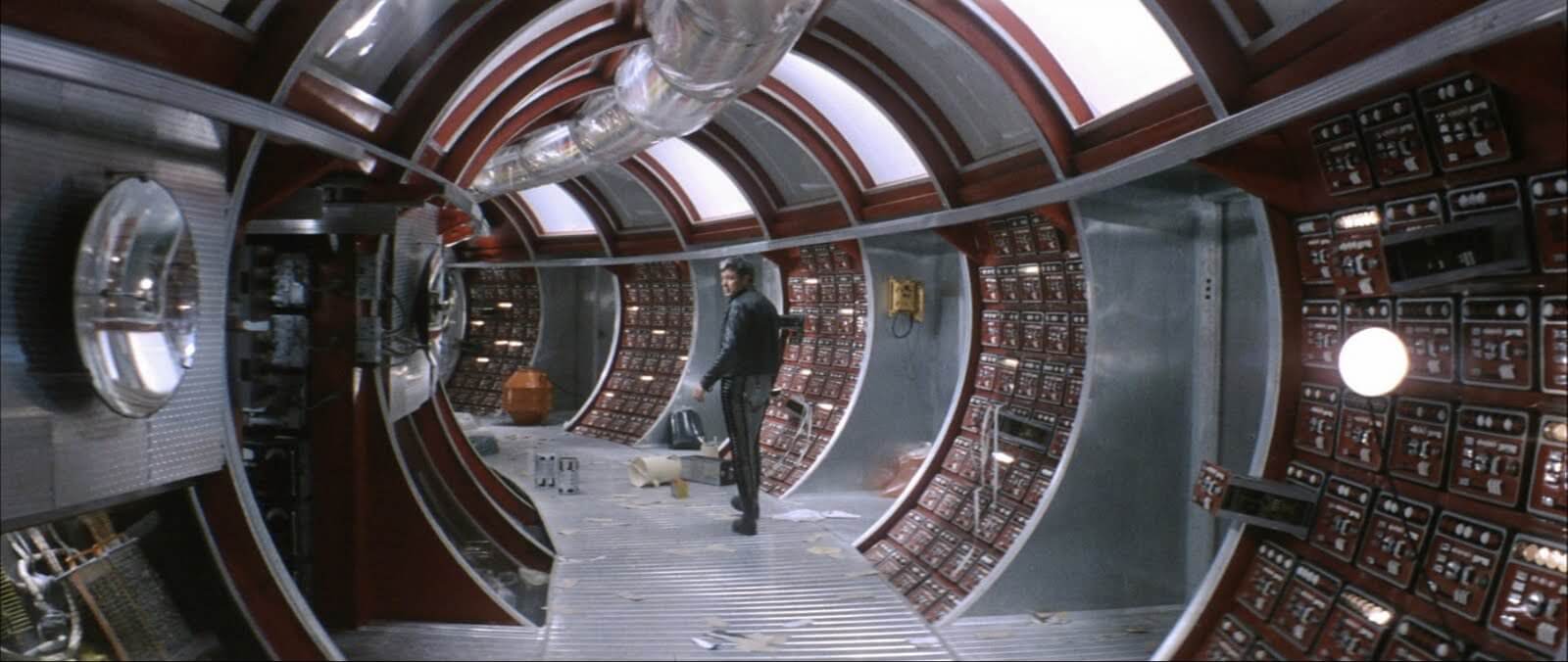

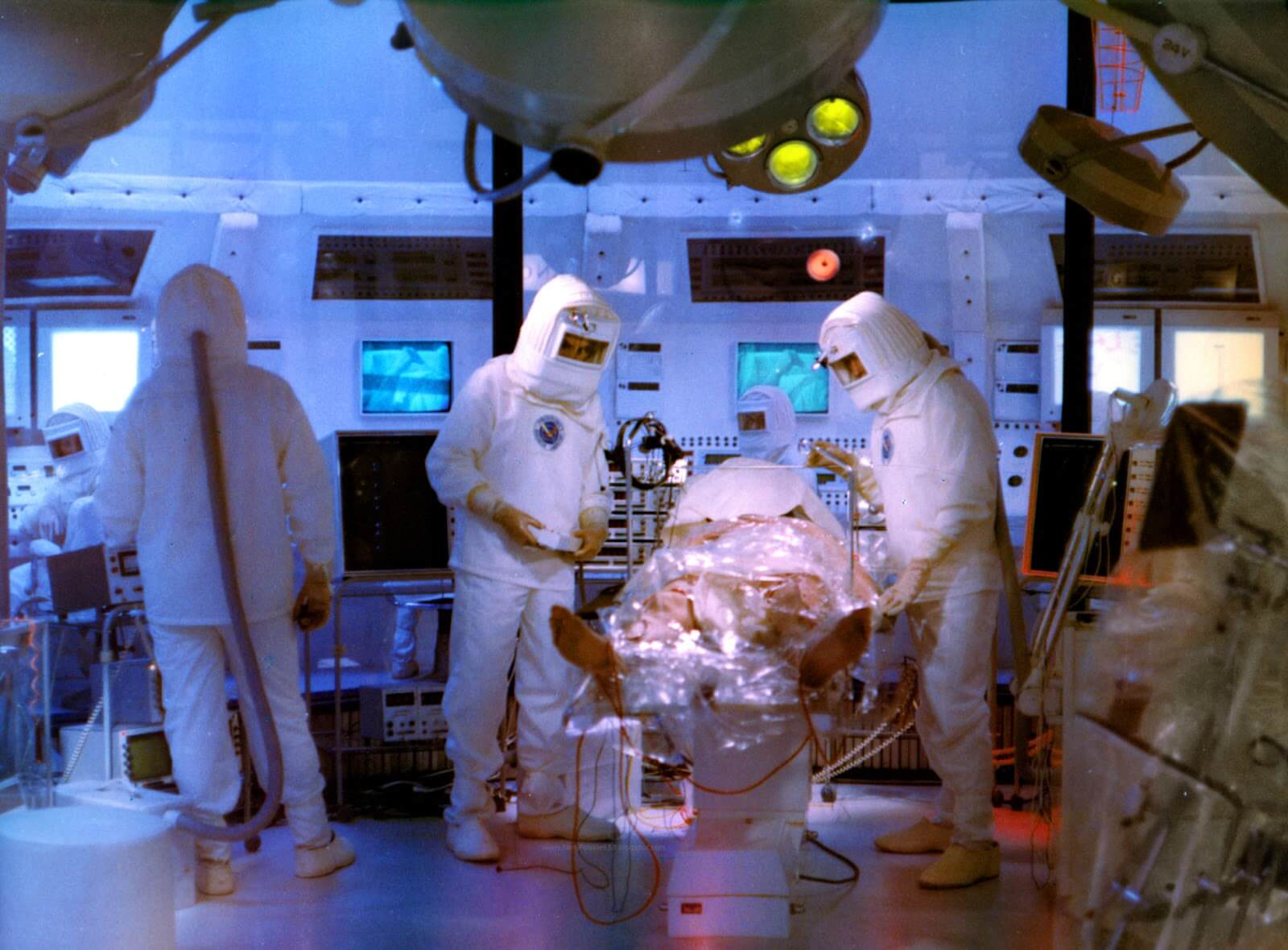

Tales of Pirx the pilot was screened for the first time in Hungary. In 1972, director András Rajnai made a television series based on them. Pirx was played by János Papp, and the soundtrack used songs by… Pink Floyd. A year later, the young Polish director Marek Piestrak made a 34-minute TV adaptation of Investigation, one of the few non sicif crime stories by Stanislaw Lem. Piestrak apparently developed a taste for Lem (much to the author’s despair), choosing the short story The Trial for his cinematic debut, considered by many to be the best part of Tales of Pirx the pilot. Filmed in 1978 (premiered in 1979), in co-production with the brotherly cinematographies of the then Soviet republics, Estonia and Ukraine, Pilot Pirx’s Inquest tells the story of the Goliath spaceship expedition, on board which there is a copy of the robot, the so-called finite nonlinear. Pirx’s task, as the commander of the expedition, is to assess its usefulness in the conditions of a manned mission consisting of a human team. Commander Pirx doesn’t know which of the crew is not human, he doesn’t even know how many robots are on board. The psychological warfare begins. Crew members denounce each other to Pirx, someone sabotages on-board equipment, someone drops Pirx a videotape with a robotic warning. Finally, Goliath reaches the rings of Saturn…

Stanisław Lem masterfully described the conflict between robot perfection and human imperfections, which will seemingly turn out to be Pirx’s greatest and only weapon in the fight against the machine. A robot committing the sin of pride, was unable to compete with purely human features. Lem’s idea, constituting the dramatic axis of Pilot Pirx’s Inquest, seems to be absurd only at first sight. The transfer of rivalry from areas of strength to areas of weakness has been well rendered on the screen, although it is certainly due to the brilliant literary prototype. Marek Piestrak made Pilot Pirx’s Inquest with all the flaws that characterize the director’s later, increasingly bizarre films. On the one hand, the bold idea of making the first Polish film with an action in space, the name of the famous writer in the lead and the tone of absolute seriousness, which, unfortunately, was at odds with the set design vision, which time had treated extremely cruelly. The laboratory equipment at the beginning of the film looks like a repository of ancient oscilloscopes today. It is similar with the wheelhouse of Goliath. Computer screens look like lighted arcade boards, and real screens act as TV sets coupled with cameras. The thrust levers, look like levers at railway switches. Goliath shoots a flame from the nozzle like a burner, and Saturn’s rings resemble a sponge up close. And with the stubbornness of a maniac, Marek Piestrak ordered to add annoying sound effects to every technological trinket, as if each device was to buzz first and then work. I understand that in this way the director wanted to get the so-called. “sci-fi effect for the mass viewer”, meaning the weirder the better. Only, years later, this effect is simply embarrassing.

Earth sequences are also a catalog of shortcomings. The communication artery of the future is the famous “concrete highway” near Wroclaw, with advertisements of the late Pan-Am airline (an interesting paradox – socialist cinematography, showing that in the future only imperialist concerns will remain). New York skyscrapers imitated skyscrapers filmed in Paris. But the camera lens caught the streets where, instead of American vehicles, Citroens, Peugeots and Renaults drove. In turn, the impressive scenery of the Moscow airport terminal was probably used on the principle: “when it’s standing, we’ll shoot it.” Therefore, during the projection, we can get bored with the absolutely unnecessary scene of Commander Pirx traveling among the conveyor belt, glazed corridors of the arrivals hall.

A nod to Lem was the command issued by Calder to the computer: “give me the area of approach to Saturn according to Stanlem’s star route”. Such a bonus, however, failed to convince Lem to try Pilot Pirx’s Inquest, which he treated no less cruelly than the previous screen adaptations of his own work. The above-mentioned sin of pride of a non-linear person was also passed on to Marek Piestrak, who instead of fully trusting Lem’s literary mastery, began to significantly correct and distort it; excellent dialogues were cut and only snippets remained on the screen. The Trial treated literally could not bring a good screen effect, but there was material for an excellent SF thriller film, with strong philosophical overtones. Unfortunately, Marek Piestrak felt smarter and that’s why Pilot Pirx’s Inquest can be perceived today only as an exotic attempt to create a good, domestic SF movie, from which only single, excellent episodes have survived.

Subsequent adaptations

In the same year, Edward Zebrowski made Hospital of the Transfiguration, a screen adaptation from a radically different genre. The action of this drama takes place during the Nazi occupation in a psychiatric hospital that is liquidated by the Germans. The main figures of doctors and patients represent different moral attitudes towards the inhuman conditions in which they had to live. The film adaptation is regarded as one of the most outstanding screen adaptations of Lem’s prose, although the author, as usual, hammered the creators: “The relatively good reception of Zebrowski’s work irritated me, because on the screen I saw only various elementary nonsense, which I couldn’t write. It wasn’t enough for the director that Sekulowski committed suicide, he also made him lick poison off the carpet. Most likely, the Germans would have killed the patients, but not the doctors who had a chance of survival. There was a lot of such nonsense in the film, and I am a doctor by training and could not afford to write irresponsible medical lies. All these shortcomings seem to me however, they are of secondary importance to the film, which is above all a very bold parable of human fate in times of enslavement. Every enslavement.” (*)

The year 1978 brought the second, this time full-length film adaptation of the crime drama Investigation, entitled Un si joli village, which was made by the French director Etienne Perier, and Lem had a modest part in the creation of the script. In 1992, the Polish director Maciej Wojtyszko, specializing in children’s films and the performances of the Young Viewer’s Television Theater, made Professor Tarantoga’s Expedition for the Television Theatre, based on a supporting character from The Star Diaries. This modest attempt at transferring the Lem grotesque to the small screen unexpectedly appealed to Lem, unlike the German adaptation attempts (on both sides of the Iron Curtain, where the adventures of Ijon Tichy’ mentor were also filmed). In 1988, the Dutchman Piet Hoenderos directed the film Victim of the Brain, loosely based on the themes of The Peace on Earth, published a year earlier, one of the last science fiction novels by Stanisław Lem. In 1994, the SF film Marianengraben was made in Germany, directed by Achim Bornhak, based on Lem’s original (!) script.

In Poland, it was only in 1997 that Waldemar Krzystek made the third adaptation of Investigation for the Television Theater with Mariusz Bonaszewski, Jerzy Gralek and Mariusz Benoit in the lead roles. As you can see, since Pilot Pirx’s Inquest, Polish creators have not been eager to adapt the prose of one of the most outstanding and most widely read scifi writers in the world (even the brilliant works of Henryk Sienkiewicz have not been translated into so many foreign languages).

The directors taking on Lem’s works were unceremoniously blasphemed by the Author himself. One of the few exceptions was Wajda, but Lem’s gracious opinion can be traced to the fact that he wrote the screenplay of Layer-cake himself. I would not like to be too bold in speculation, but it turns out that Stanisław Lem clearly did not tolerate the very phenomenon of film adaptation. One can understand his stubbornness when he once called Tarkovsky an idiot, assuming that any attempt to look at Solaris in a different way must end his life on intellectual astray, diametrically opposed to the writer’s intentions. But such short circuits happen even to the best. Stephen King hated Kubrick for his brilliant adaptation of The Shining. Hampton Fancher, David Peoples and Ridley Scott also extracted from the short story Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep by Philip K. Dick (the only American science-fiction writer whom Lem sincerely admired) only what was suitable for building a fascinating story told in Blade Runner.

Solaris (2002)sol

Stanisław Lem, as one of the greatest SF writers in history, firmly distances himself from SF films. His devastating opinions, aiming mercilessly with intelligent error scoring, were not, however, able to scare away many enthusiasts, ready to make subsequent screen adaptations of his most famous novel, Solaris. Among them was the actor Richard Gere, as well as an American millionaire who wanted to make a movie in Earth orbit. Absolutely nothing came of these bold concepts, except royalties. Finally the great James Cameron himself became interested in Solaris. Apparently, the first time he bought the rights to the film from the alleged Russian owner of the rights to the film adaptation. However, the papers of the Russian contractor turned out to be a forgery… Eventually, Lem himself sold the film rights to 20th Century Fox, and the film was produced by James Cameron’s Lightstorm Entertainment. He initially wanted to sit on the director’s stool himself, but eventually chose Steven Soderbergh for the position, contenting himself with the role of a producer (and rightly so – can anyone imagine a modest SF drama in the hands of the grandmaster of a great spectacle?).

Psychologist Chris Kelvin arrives at a research station suspended above the surface of the planet Solaris. His task is to solve the mystery of the inexplicable behavior of three members of the station’s crew. Once there, Gibarian is found dead, and Gordon and Snow hide something related to suspicions that the ocean covering Solaris is an unusual form of intelligent life. Soon Kelvin becomes convinced of the influence of Solaris. Here, his tragically deceased wife, Rheya, materializes in front of the psychologist…

Lem knew from the beginning that the American adaptation of Solaris would not follow his lead. Instead of confronting people with the incomprehensible powers of the thinking ocean, readers and viewers received an extraordinary film about love. Soderbergh had the bold idea of combining 2001: A Space Odyssey with Last Tango in Paris. A somewhat breakneck fusion, intellectually far from Kubrick’s masterpiece, feeding rather on his elegant frames and unhurried narration. In the novel, Lem was able to devote eighteen pages to amazing descriptions of the waves tossing the surface of the ocean. The book is filled with a mystical atmosphere of meeting the Unknown, and the plot of Kelvin’s tragic love for the deceased, re-created for him by the ocean Harey, was more a means than an end.

On the other hand, Steven Soderbergh, a director who likes to psychologically dig into the recesses of the souls of his twisted heroes, was interested in analyzing the love story between Kelvin and Harey. Science fiction has been relegated to the role of decoration and a driving force explaining the origin of human phantoms. The cosmos no longer emanated magic. For the director, it became interesting only when problems brought from Earth were inserted into it. Soderbergh and Cameron chose a rather radical attempt to read Solaris, which was far from Lem’s thought and inconsistent with readers’ expectations, but equally fascinating in its own way. The ocean itself is very sparingly present on the screen. What we got in return was an unbearably large number of Kelvin’s teary earthly flashbacks. I don’t know why Soderbergh made the personal/gender changes. He renamed the scientist Snaut Snow, and the white man Sartorius became the black woman Gordon. Political correctness to cast an African American at any cost? Or maybe the director wanted to emphasize the ethereal beauty of the wonderful Natascha McElhone by contrasting her with a black actress with a beauty from a completely different aesthetic fairy tale? Gibarian’s name stuck, but his character only appeared on screen in a cameo, so it was possible not to bother with his personal details. But while the change from Kris Kelvin to Chris Kelvin was just cosmetic, changing Harey’s name to Rhey is somewhat nonsensical.

Looking at Solaris only from the perspective of a film, it is impossible to deny Soderbergh’s ability to create its characteristic, sleepy mood, so far removed from typical American space spectacles. The lazy pace does not put you to sleep, as in Tarkovsky. The slow celebration of each frame, each dialogue and plot situation serves to effectively draw the viewer into the center of this interplanetary love story. The visual and scenographic concept is elegant, well-thought-out and coherent (Soderbergh was not only the screenwriter and director, but also the cinematographer and editor under pseudonym). The whole thing is enhanced by the amazing music of Cliff Martinez, woven from electronic noises. You can’t take your eyes off Natascha McElhone’s big eyes, and George Clooney showed that he can build a role from minimalist means of expression. As predicted by Cameron, the film failed at the box office, but the creators did not want to make a fortune on Lem. Steven Soderbergh made a moving drama of two people’s feelings, based on the work of a sober rationalist who was interested in the brain rather than the heart.

Despite missing Lem, the American version of Solaris seems to be the most mature, the most visually accurate (finally!) and the most serious artistic adaptation of the Master’s prose that has been made so far.

Summary

Looking at the list of Lem’s adaptations, one can conclude that more was not done than was done. Only three novels and a few short stories, for a dozen or so novels and as many collections of short stories. Why so little? The reasons were explained earlier – firstly, the money, secondly, the lack of talented adapters with a reliable key to converting letters into frames, while maintaining the Lem spirit. The list would be a bit richer if Aleksander Ford succeeded in filming Return from the Stars, a novel almost 20 years ahead of the trend of Polish sociological fantasy, whose master was Janusz A. Zajdel. Apparently, Return from the Stars was originally written as a screenplay. It was only when the director capitulated to the budget and technical obstacles that Stanislaw Lem turned the script into a normal novel… In turn, Andrzej Wajda wanted to bring the phenomenal Futurological Congress to the screen in the 1970s, but his intentions again crashed into an empty wallet . Around the same time, American producer Michael Rudesone bought the film rights to The Invincible, but good intentions went astray again. Disney was once interested in The Star Diaries. These are just the most important of many examples of production and artistic impotence in the face of Lem’s books. The author himself sarcastically admits that in most cases it was a good thing. An adaptation satisfactory to the Master would require a cinematic genius like Kubrick, and the vast majority of Lem was approached by artists about whom little was known or who were quickly forgotten (after all, 2001: A Space Odyssey was not to Lem’s taste too).

But for all his aversion to screen sci-fi, Lem clearly points to The Invincible as the perfect novel material for constructing an epic movie spectacle, with plenty of action, special effects, extraterrestrial landscapes and unusual forms of extrahuman intelligence. Maybe someday some SF from across the ocean will pay attention to this novel? I’m thinking that with today’s aggressive Hollywood policy of grabbing ideas for films from everywhere, it is only a matter of time before this concept-devouring wave reaches Lem, and the lists of possible film adaptations must have been lying in the safes of major studios for a long time, waiting for the green light. What else? Return from the Stars would be an excellent SF drama, staged in the metropolitan setting of Blade Runner. The Futurological Congress has already been remade into The Matrix. Not literally, but anyone who has read it can have no doubts about where Neo and the idea of an illusion that is being pumped directly into humanity’s heads came from. There are faint echoes of the His master’s voice in Zemeckis’ Contact. Only crazy Tim Burton would be suitable for filming Cyberiad. The grotesque The Star Diaries, in turn, could repeat the success of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy if properly treated. And Tales of Pirx the pilot would work entirely on the small screen, as a 10-episode series-superproduction, enriched with the adaptation of Fiasco, which also features the pilot Pirx. I would see only a few episodes from this excellent collection of short stories in the cinema.

The conclusion suggests itself – with Lem it is safest to take only what guarantees a dynamic spectacle at an appropriate level. Purely problematic works, in which the action recedes into the background, in the face of overwhelming moral and philosophical issues, have no raison d’être in the land of moving pictures. The most you can do is perform the Soderbergh maneuver. His Solaris looks impressive, but it is an example that a good film according to Lem inevitably has to move away from Lem. And then it’s hard to talk about a film adaptation, rather a variation on a theme. We will see. But the Author himself will no longer experience it. Stanisław Lem died on March 27, 2006 in Krakow, at the age of 85.

(*) – quotes from Łukasz Maciejewski’s interview with Stanisław Lem, published on the website www.lem.onet.pl