YOJIMBO. The Immortal Classic That Inspired Sergio Leone

Yojimbo is not only a classic of samurai cinema but also a precursor to the spaghetti western. After all, the beginning of this Italian genre is dated to 1964 when Sergio Leone completed A Fistful of Dollars.

It was not so much a remake of Kurosawa‘s Yojimbo as a plagiarism, as the producers did not want to pay for using the ideas from the screenplay written by Kurosawa and Ryûzô Kikushima. A lawsuit ensued, which the Japanese won, thus earning more from the Italian western—a production that turned out to be more profitable than the original Japanese film.

I make a living by killing, and this town is full of people who deserve to die.

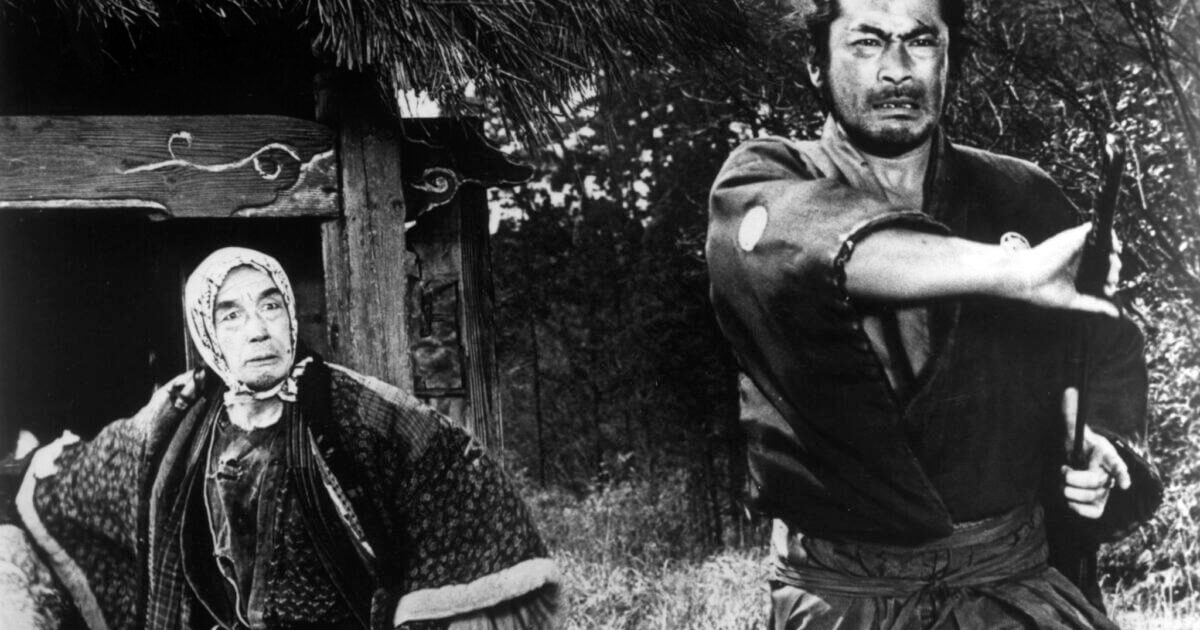

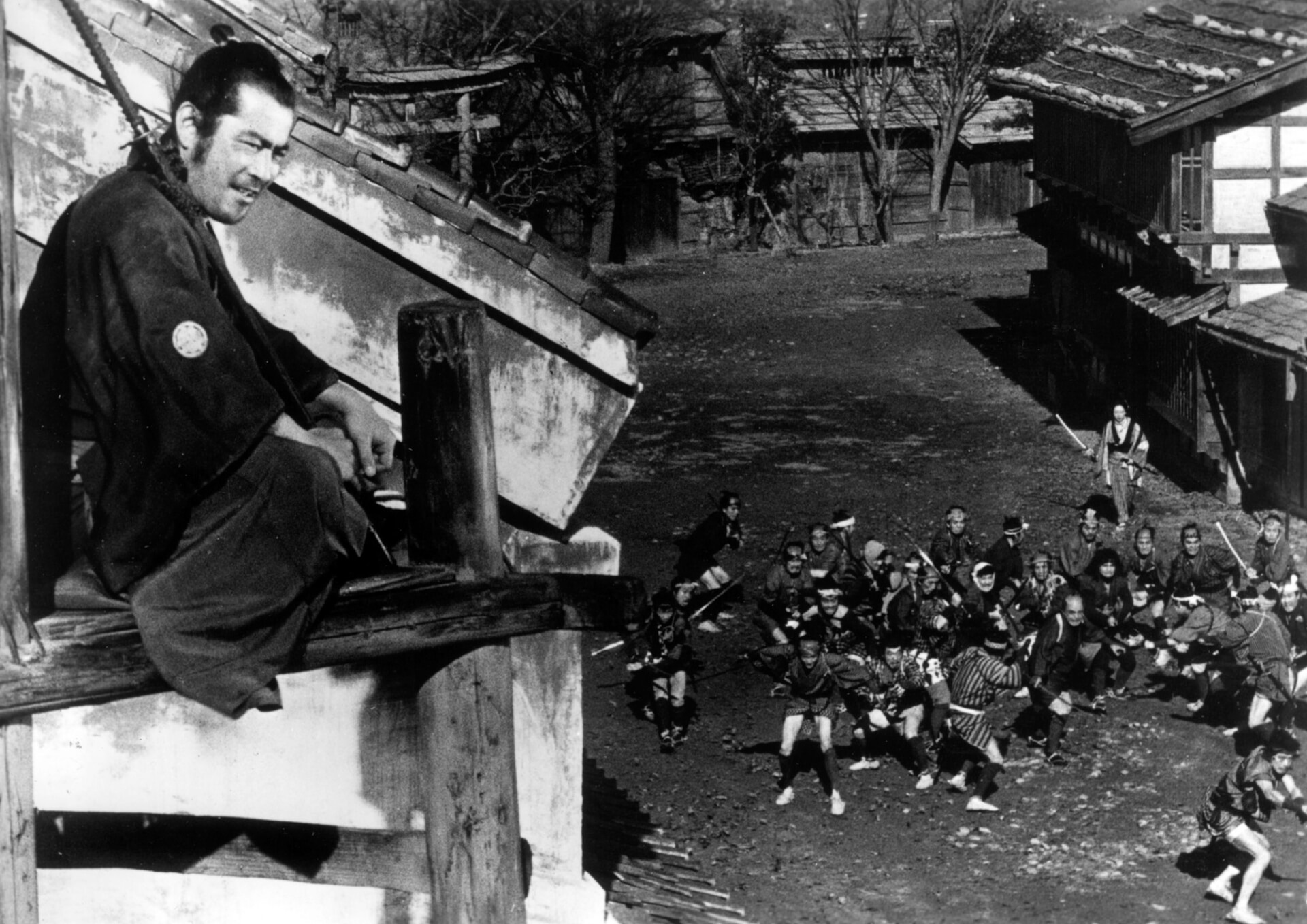

The life of the ronin Sanjuro is like a camellia flower flowing along the river’s current—he himself does not know where he is going, nor how long he will stay afloat. At a crossroads, he throws a stick to show him the way. And so he arrives in a town ruled by two gangs fighting for supremacy. In times of peace, this masterless samurai does not intend to take sides in the conflict, only his own. He lives by killing and intends to use this skill to earn a handful of ryō for his upkeep. To this end, he becomes a bodyguard, secretly plotting against his employer. But the boss does not intend to be fair to him either—after winning the fight, he plans to get rid of the samurai and thus save a handful of gold coins.

Sanjuro is decidedly a positive hero of Yojimbo. He does not forget the code of honor and defends the weak, even giving them his pay. There is a moment when he watches a massacre helplessly, hiding in a barrel, but that’s because he is seriously injured and coming out of hiding would be suicidal. His character is inspired by American westerns about riders from nowhere who, by defeating local bandits, earn the gratitude of ordinary citizens, mainly farmers (the flagship work of this type is Shane from 1953). The Asian equivalent of the western “good bad guy” later appeared in films: Sanjuro (1962, directed by Akira Kurosawa) based on a novel by Shûgorô Yamamoto, Zatoichi Meets Yojimbo (1970, directed by Kihachi Okamoto), and Ambush (1970, directed by Hiroshi Inagaki) – all featuring Toshirô Mifune in the role.

What difference does it make whether you kill one or a hundred people? They’ll hang you only once.

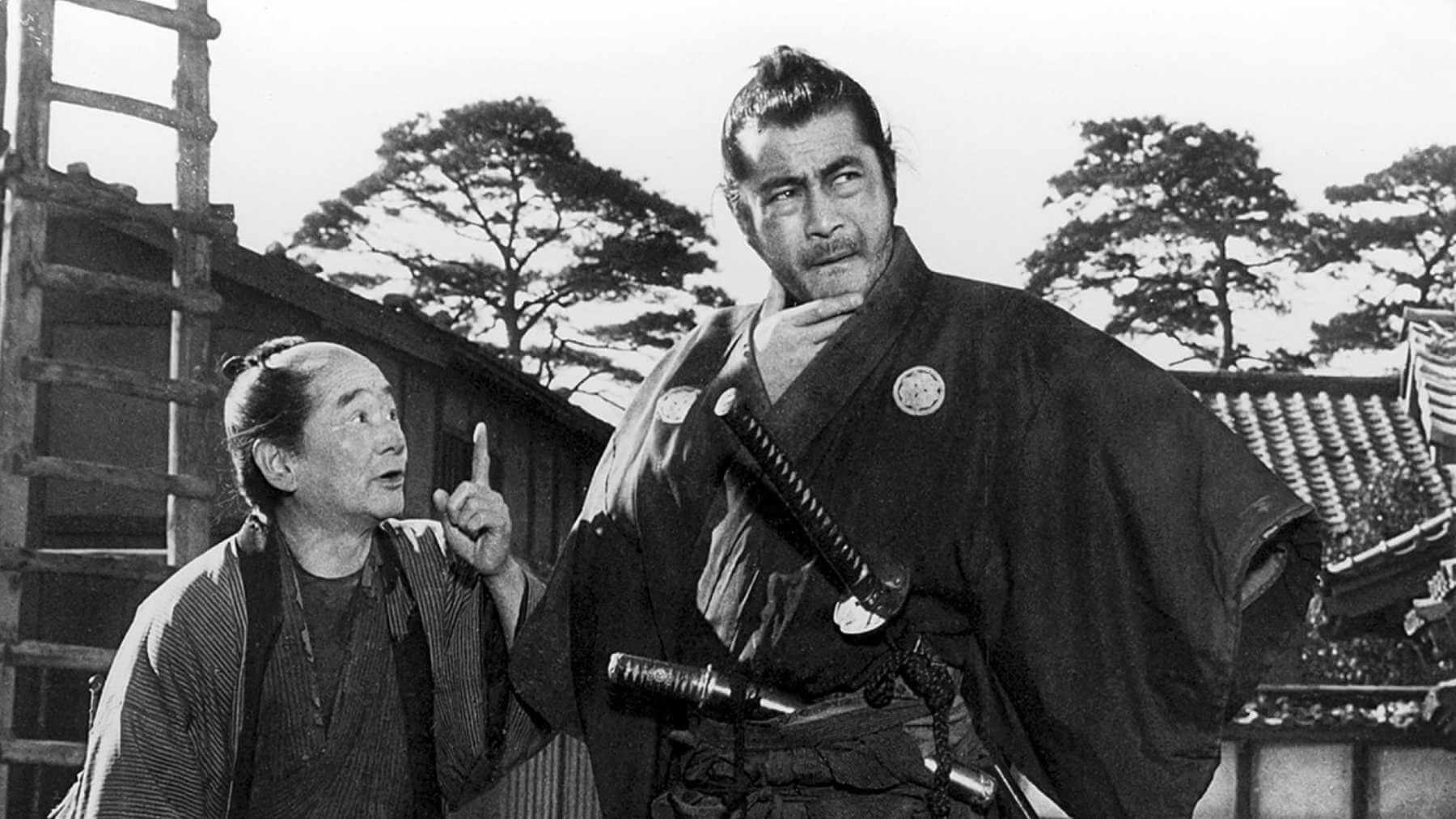

It is hard to overestimate the contribution that the creator of Rashômon (1950) made to the world of cinema. An author who adapted the works of Fyodor Dostoevsky (The Idiot, 1951), Leo Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky (The Lower Depths, 1957), and William Shakespeare (Throne of Blood, 1957) reached Western audiences much more easily than other native creators. After the release of the western The Magnificent Seven (1960), inspired by Kurosawa’s classic, people paid even more attention to the works of the Japanese master and his actors. Particularly impressive was the instinctive and often expressive acting of Toshirô Mifune, who won his first Volpi Cup for Best Actor at the Venice Film Festival for his role as the bodyguard Sanjuro. He received his second such award four years later for the film Red Beard, which unfortunately marked his last appearance with the “emperor of Japanese cinema.”

An actor with directorial ambitions, who made his only film in 1963 (The Legacy based on a script by Ryûzô Kikushima), he eventually quarreled with his favorite filmmaker. Their collaboration ended, but the actor continued to shine on the international stage, mainly in monumental roles of historical figures. When Kurosawa was making his last super-productions—Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985)—he had a new favorite actor, Tatsuya Nakadai, who debuted in Seven Samurai (1954) and had significant roles in films by another Japanese cinema master, Masaki Kobayashi (the anti-war trilogy The Human Condition, 1959-61). Nakadai was excellent in samurai dramas like Harakiri (1962), Samurai Rebellion (1966), and Goyokin (1969), and he also developed his talent in theatrical plays (particularly in Shakespearean repertoire).

Of course, I wouldn’t mention Tatsuya Nakadai if he hadn’t played a significant role in Yojimbo. Unosuke, the character he portrayed, symbolizes the approaching modernization of the country. He does not carry a sword but an American firearm, a Smith & Wesson revolver—a brand later favored by Clint Eastwood in the Dirty Harry series (1971–88). The gunfighter in Kurosawa’s film believes that with such a weapon, he has a significant advantage. He is partly right, as it is difficult to defeat an opponent from a distance with a samurai sword. A knife, however, is another matter. The masterful duel in the finale (knife versus revolver) between Sanjuro and Unosuke has inspired filmmakers many times. In the Italian The Big Gundown (1966) by Sergio Sollima and the American El Dorado (1967) by Howard Hawks, we see characters with knives challenging armed fighters, but perhaps the closest to the Japanese original was Walter Hill in The Warriors (1979). The same Hill presented his own version of Yojimbo years later titled Last Man Standing (1996).

Stop crying—it’s pathetic. I hate pathetic people—I’ll have to kill you.

Japanese policies aimed at building military power resulted in a negative perception of the Japanese for many years, viewed as aggressors and perpetrators of many misfortunes. Therefore, after World War II, they had to strive hard to gain respect and recognition. They quickly achieved victory in the film field—since Rashômon (1950), Japanese studios have produced many wonderful films that won awards at festivals and are now considered classics of cinema. This good streak lasted until the 1970s when the Japanese sun began to set, and Kurosawa could only make one film every five years. Even during the crisis, however, he created outstanding works, skillfully using Russian (Dersu Uzala based on Vladimir Arsenyev) and English literature (Ran based on William Shakespeare’s King Lear).

Yojimbo is a classic sword drama (ken-geki), in which the hero played by Toshirô Mifune kills his opponents in a few swift moves. This cinema is very visually expressive, conveying much about the world through meaningful images. When Sanjuro arrives in town, he sees a dog running down the street holding a human hand in its mouth. At that moment, the newcomer realizes that this is no ordinary town, but a battlefield. And thus, an ideal place for a samurai. His skills are impressive, so it is worth knowing who trained him. The fight scene instructor was Yoshio Sugino, who taught judo and iaidō (a form of Japanese swordsmanship slightly different from kendo) in his dojo. His expertise was also utilized in Seven Samurai (1954) and The Hidden Fortress (1958). In creating the fight choreography, he aimed to move away from the artificiality preferred in kabuki theater in favor of realism.

A truce is merely the seed from which an even greater battle will grow.

Yojimbo achieved its visual impact thanks to the support of Kazuo Miyagawa, one of Japan’s most outstanding cinematographers (he worked with Kurosawa only three times, the first time on Rashômon and the last as a consultant on Kagemusha). Kurosawa himself edited the film, introducing his favorite optical effect, the wipe, which usually symbolizes a short passage of time. This technique was perfect for this film, as the action takes place over a short period, and the characters have no time to sleep, always having to stay alert to avoid being assassinated. The contribution of composer Masaru Satô to the film’s atmosphere cannot be overlooked. His music, with a motif played on drums, is like an accelerated heartbeat—introducing a note of anxiety, foretelling misfortune.

It is also worth considering the screenplay, on which Kurosawa collaborated with Ryûzô Kikushima (this was their seventh joint project, including one film not directed by Kurosawa). Did the character they created have any precedent in literature or Western cinema? It is very possible that this film would not have been made without the work of American crime novelist Dashiell Hammett. The Japanese screenwriters drew ideas from his two novels: Red Harvest (1929) and The Glass Key (1931). Kurosawa and Kikushima created a character inspired by Hammett’s “man with no name”—a cynical hero caught between the clinking purse of coins and a sense of duty and justice, related to acting for the good of a community afflicted by violence and lawlessness. Unfortunately, Hammett died in January 1961—eight months before the American premiere of the film.

I see the entrance to hell—I’ll be waiting for you there.

In my opinion, Yojimbo is not as brilliant as the immortal classics: Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958), and the later films Dersu Uzala (1975) and Ran (1985). However, it is still a piece of solid craftsmanship, adorned with excellent dialogues and evocative scenes filmed from multiple cameras and various angles. The sound design and visual composition are impeccable. The set design and costumes allow the audience to immerse themselves in the atmosphere of the Edo period’s twilight. Moreover, Yoshirô Muraki’s costumes were nominated for an Oscar (although the award went to Italian designer Piero Gherardi for La Dolce Vita). Yôjinbô is not only the prototype for A Fistful of Dollars and an unofficial precursor to Italian westerns, but it is also an excellent example of the Japanese school of filmmaking and a showcase of the prowess of one of its most outstanding representatives. Every filmmaker, regardless of nationality (Asian, European, or American), would want to be his student.