VIDEODROME. Body horror of your face glued to a screen

I can’t imagine the impact Videodrome had on the audience on its premiere day. Sex and violence in various proportions combine here with the influence of the media – equally harmful as they are stimulating the brain. At the same time, the viewer’s gray matter will be activated by the fact that Videodrome is not only a hodgepodge of genres but also contains elements that are disturbingly relevant even today. Maybe even more so than before.

Everything, from soft pornography to brutal violence, is briefly depicted in the schedule of the small private station, Civic TV, whose director is Max Renn (James Woods). He sees nothing wrong with controversial content because, in his opinion, it gives people what they want to watch, and they can’t find it anywhere else. In search of new and more powerful materials for his channel, he relies on pirate transmissions. Harlan (Peter Dvorsky) is responsible for finding them. When he shows his boss snippets of Videodrome – a plotless, disturbingly realistic scene of young women being tortured by masked captors – Max becomes fascinated by the brutality and directness of the program. He wants to incorporate it into his station’s lineup. He then initiates an investigation aimed at leading him to the creators of Videodrome, whoever they may be.

Besides that, Max wonders: is it a directed show for a select audience, or is it a real transmission from the torture chamber?

To discover the answer to this and many other questions, the protagonist must delve into the media-centric underworld, which he has only known superficially. Through his connections with the pirate underground, he stumbles upon the trail of the media guru, Professor Brian O’Blivion (Jack Creley), who might have better information about the mysterious program. Max’s investigation, his appearance, and mannerisms, as well as the development of the plot, bring to mind film noir. And that’s not surprising. This subgenre of cinema emerged in the post-war era, reflecting concerns about the future and the development of mass culture, which plays an important role in Cronenberg’s film. Moreover, these “noir” elements can be specified: we have the femme fatale in the form of Nicki Brand (Debbie Harry), an attractive psychologist who enjoys sadomasochistic games; we have a cynical detective figure in a trench coat who smokes cigarettes, increasingly immersed in the investigation, which complicates his judgment and complicates the case; we have a world saturated with corruption (pornography dealers, illegal experiments); and to complete the package, we have a complex plot full of subplots and additional meanings.

All of this harkens back to film noir, and it does so in a creative and original way, as it combines elements known from classic cinema with modernity, which is not always successful. Here in Videodrome, not only does everything fit together, but it also contributes to the world we know, which is seasoned with a touch of perversion and a stack of videotapes.

Television will change your mind. Videodrome will change your body.

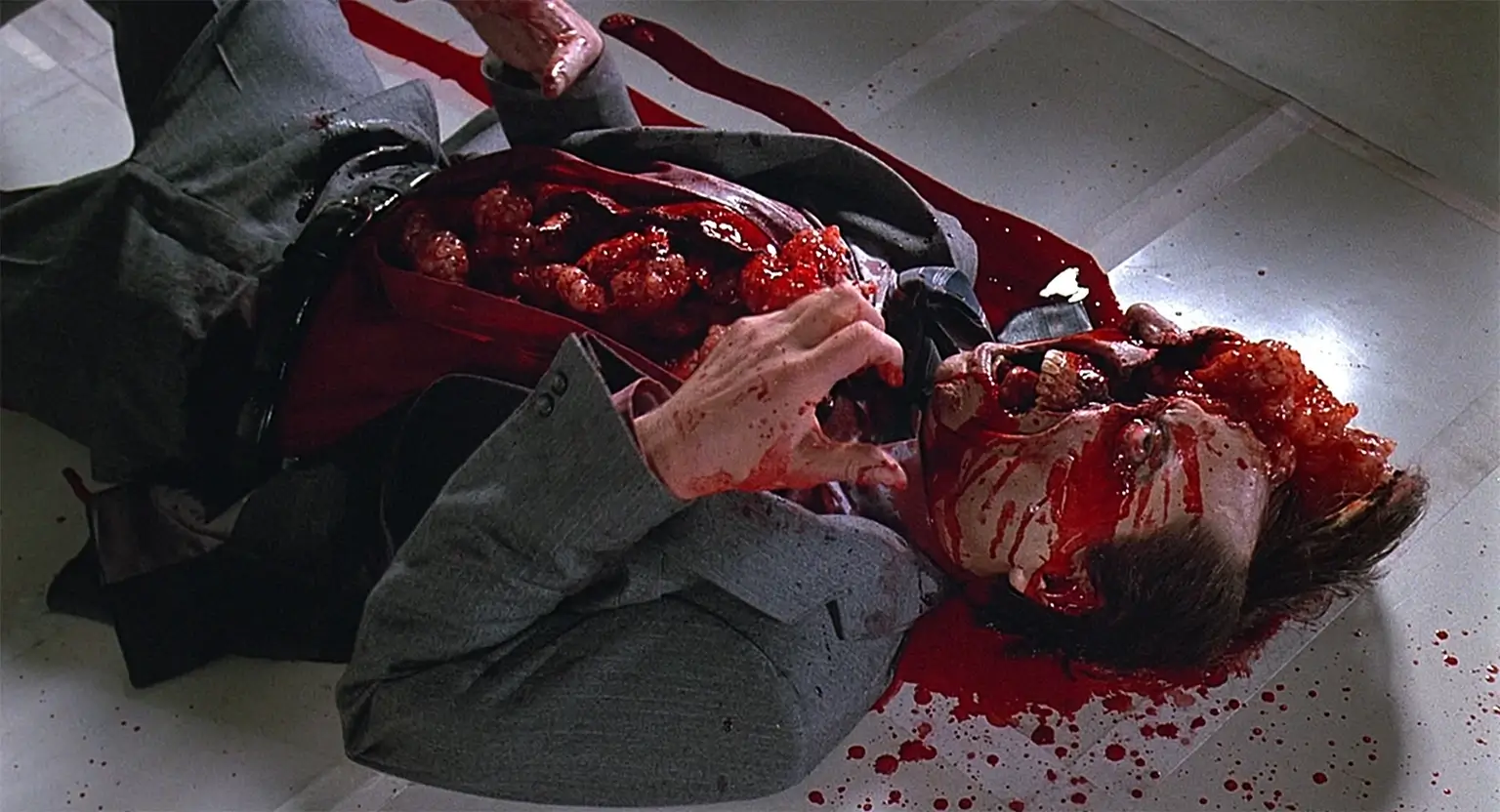

The above quote, taken from the trailer, succinctly captures how the titular program works (or more precisely, the signal broadcast in the background). The broader concept of technology and its impact on humans is the essence of Cronenberg’s film, as he has always enjoyed distorting the bodies and minds of his characters. He did this in various ways before. In the Venereal Trilogy (Shivers, Rabid, The Brood), the threat came from the body, sometimes through infection, sometimes through mutation. In Scanners, the protagonist was a telepath, which gave him extraordinary abilities. This time, the director combines body horror and techno-thriller. It may sound quite exotic, but Cronenberg’s work cannot be confined within the simple boundaries of a genre.

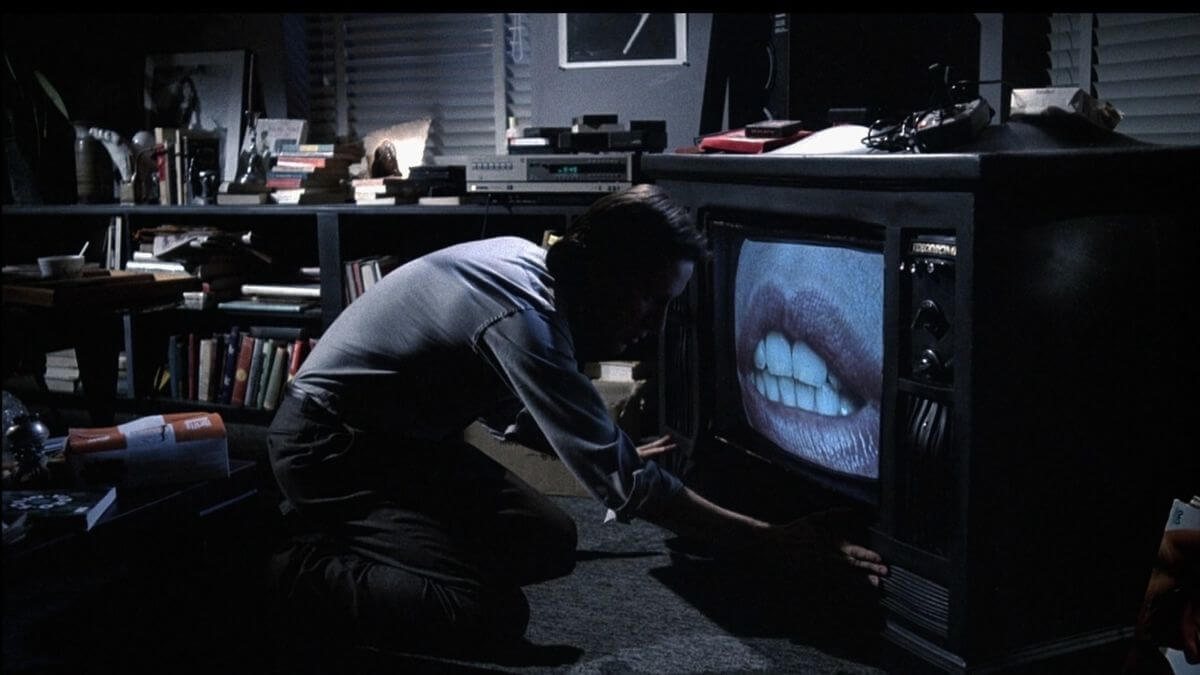

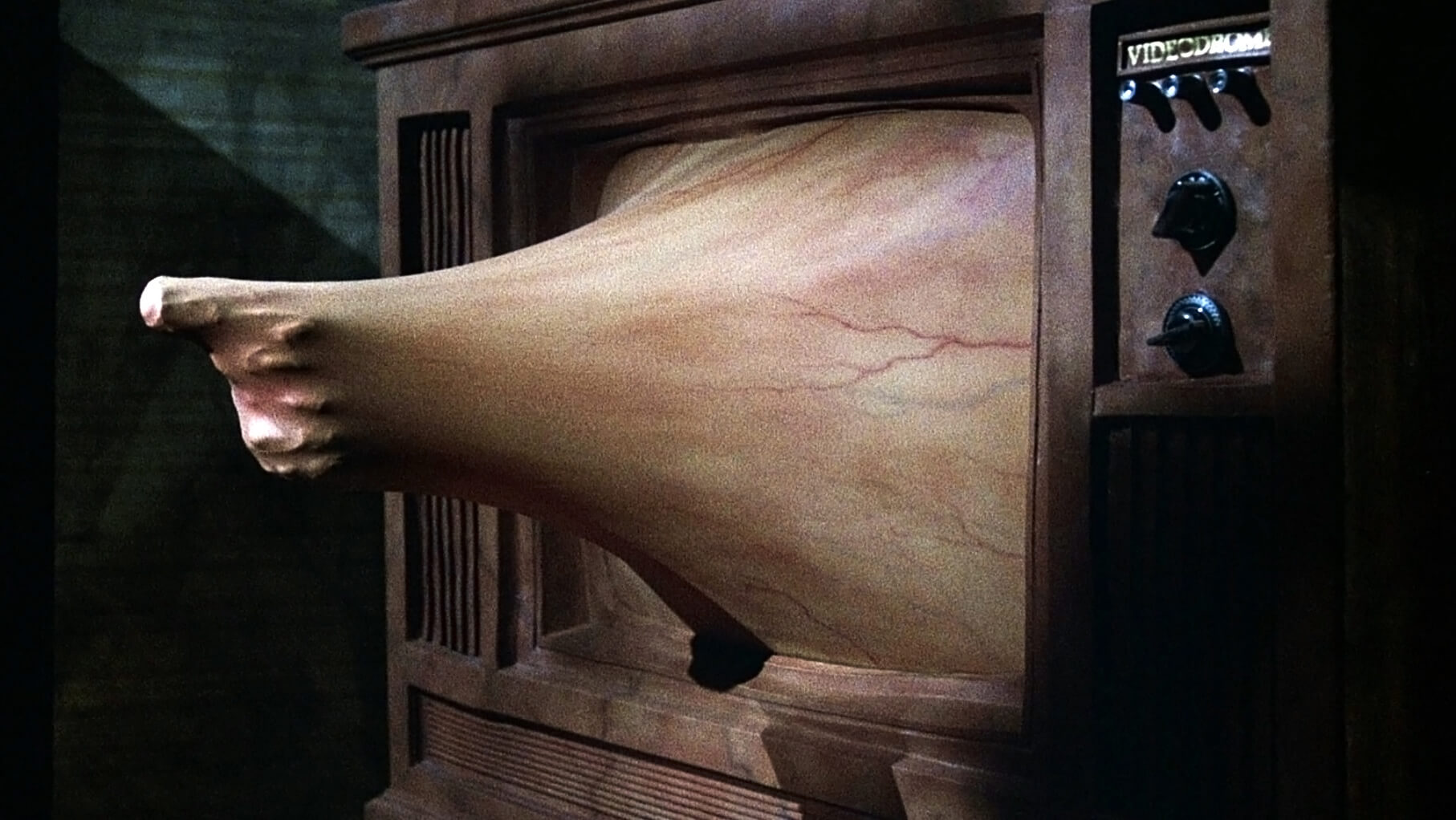

As the name suggests, in body horror, the threat doesn’t come from external sources – there are no swamp monsters or space marionettes here. Instead, there are mysterious skin infections, deadly parasites, and unsettling mutations. In Videodrome, the human body is penetrated by technology. Under the influence of a harmful television signal, Max gradually loses the ability to distinguish reality from hallucinations. Watching a videotape ends with him fondling a pulsating and sensually swollen screen filled with a close-up of a woman’s lips. In a later stage, his body undergoes changes, and he starts to resemble a human VCR, which can be programmed by inserting a cassette into a vaginal slit in his abdominal cavity.

In Videodrome, television is harmful, and this is not a metaphor.

In the film, the most to say about the impact of the glass screen on viewers is the media guru, Professor Brian O’Blivion. He is so consumed by the concept of television that he appears only through a video recording. Under the influence of the television screen’s effects, the protagonist’s brain confuses hallucination with reality. O’Blivion suffered from a brain tumor he believed was caused by constant contact with the television medium. He thought that the visions he experienced were the cause of the tumor, not the other way around. He did not see the tumor as a disease. In his view, it was a new organ in the body, adapted to receive the Videodrome signal, representing another stage in human evolution.

Sequels, reboots, and youth-oriented franchises – that’s roughly the recent history of science fiction cinema. While advancements in technology allow filmmakers to show more and do it better, theoretically enabling even the most outlandish stories and realities to be brought to the big screen, only a fraction of them deviates from established narrative patterns. Notable exceptions to this rule include the disturbingly realistic Children of Men by Alfonso Cuarón and Ex Machina by Alex Garland. It’s interesting that within a genre that, by definition, should be a wellspring of creativity and bold visions of the future, there are so few authentically fresh and original productions.

Older films that are set in the future bring another factor into play – visionary foresight. Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) showcased anthropomorphic robots, Stanley Kubrick in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) foresaw the invention of tablets, the eponymous character Johnny Mnemonic (1995) used VR goggles, and the film’s plot revolved around a civilization-threatening illness linked to electronic overuse. The “aging” of such films is an interesting phenomenon. Although the depicted world in these films doesn’t entirely reflect today’s reality, they have become classics and remain highly enjoyable to watch, with the special effects of their time adding to their charm. Yet, a science fiction film produced several decades ago that depicts a vision of the world that closely mirrors our contemporary reality is a rarity.

I can’t fathom the impact that Videodrome had on its audience on the day of its premiere, as it deals with issues relevant today but about which the viewers at that time had no idea. The film blends sex and violence in varying proportions with the harmful yet mind-stimulating influence of the media. In 1983, this was the glass screen, though most of the theories in the film, such as “television names” for everyone, seem more suited to the internet medium (where you can practically give yourself a new name, or nickname, almost anywhere). Like the internet, Videodrome is an uncontrolled media entity that expands and increasingly absorbs the human mind and body. We, much like Max Renn, consume more and more signals and transmissions, our faces glued to screens.