METROPOLIS. A science fiction film for the ages

As the First World War was coming to an end, as the first breaths of air were taken by the Paris Peace Conference, which was soon to give birth to a document stabilizing the post-war European situation, fear and anxiety ran rampant in the streets of Germany. The uncertain tomorrows kept society far from optimistically gazing into the future, one that was to be determined by the wartime adversaries. Art, like a mirror to the soul, reflected the German state of mind and returned to the stream that had already been named Expressionism before the wartime turmoil.

Anti-reality

A counter-direction to naturalism and realism, it was the perfect antidote to the gray German reality of the Paris negotiations and the Treaty of Versailles order. Expressionism, besides its place in the realms of art, music, and literature, held an esteemed position in the annals of the burgeoning German film industry, which was then under the dominion of the powerful film studio established upon the recommendation of the German General Staff, UFA.

German cinematic expressionism transported the viewer into a world – as the subtitle of one of the flagship works of this movement proclaimed – “seen through the eyes of a madman.” Creators abandoned the naturalistic gaze upon their surroundings. They scorned it to such an extent that outdoor scenes were forsaken, opting instead to confine the cinematic reality to canvas backdrops stretched across wooden frames, set up within a secluded studio, cut off from the world.

The result was something that could boldly be called anti-reality. A place where the fundamental rules ingrained in us since childhood undergo extreme devaluation. Observing this brutally distorted reality, we truly feel like participants in the fantasies of a deranged mind. Yet, amidst the fanciful forms of surrealist set designs, we can discover elements that remind us that the film was created by a sane human, that the world crafted within the studio has its indistinct reflection in everyday life, pulsating beyond its doors.

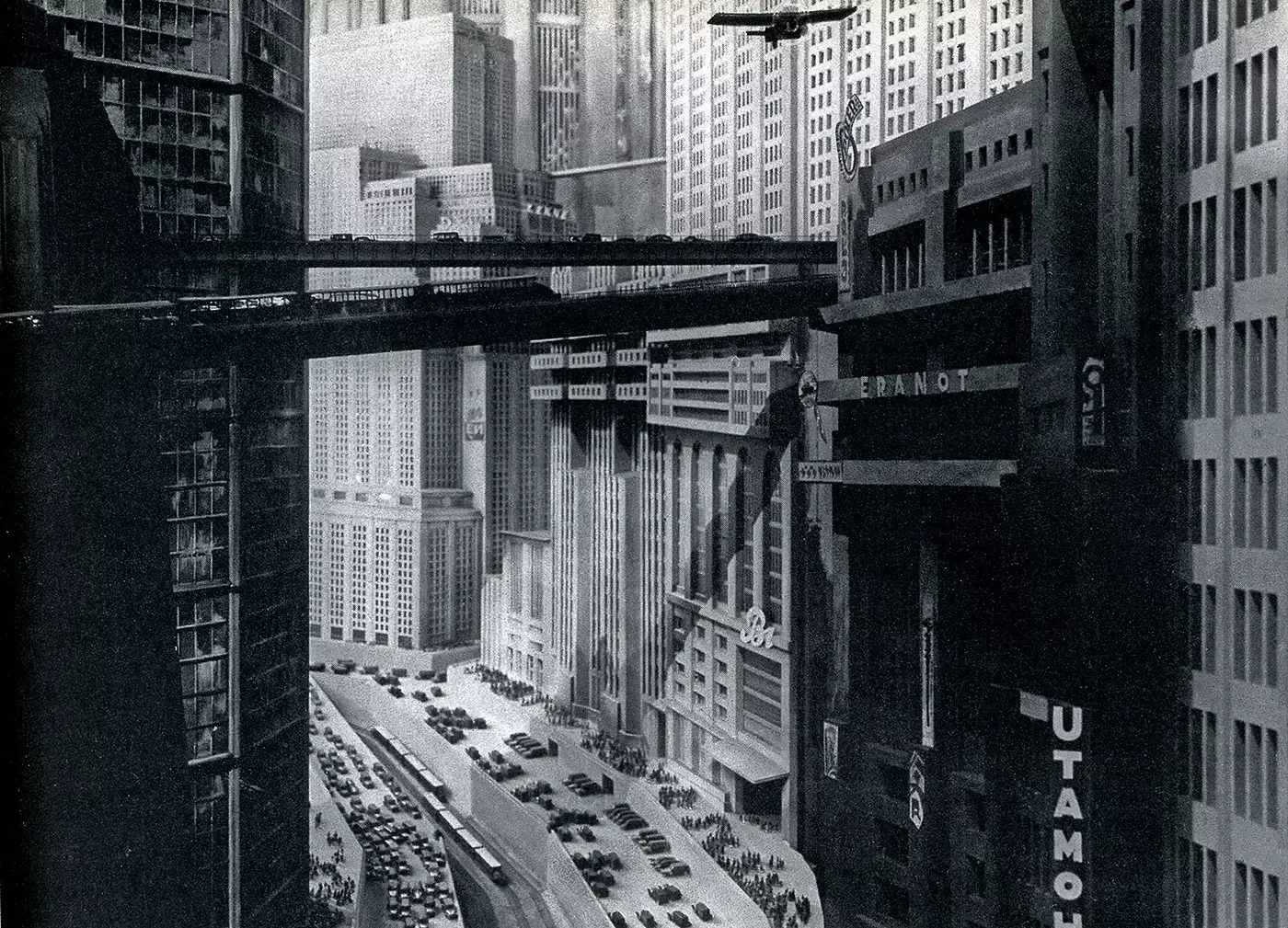

Fritz Lang’s Metropolis is a work from the twilight of the expressionist movement, officially premiering in 1927. Despite the rise in popularity of films adhering to a realistic convention during its production years, such as the cinema of Georg W. Pabst, it should be regarded as one of the monuments of post-war German stylistics. It transports us to the 21st century, depicted in an almost apocalyptic manner on successive frames of the film reel. Society is divided into two castes – the workers, akin to a horde of genderless creatures tending to the machinery located in the underground of the titular megalopolis, and the owners who inhabit the upper parts of the city.

Related:

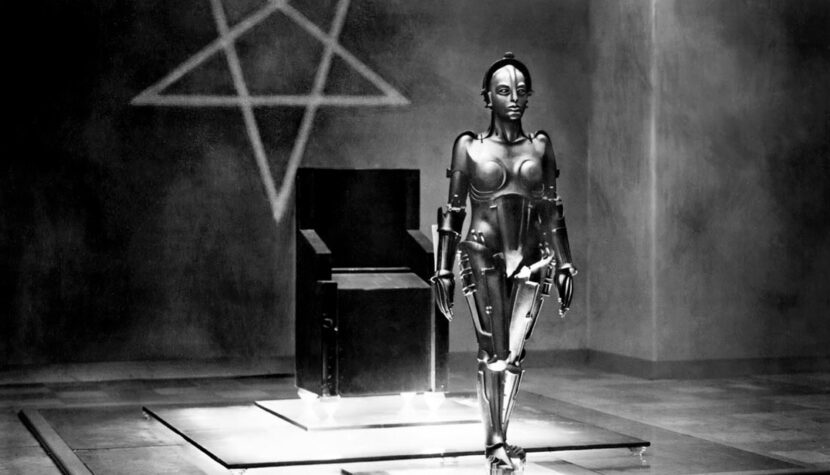

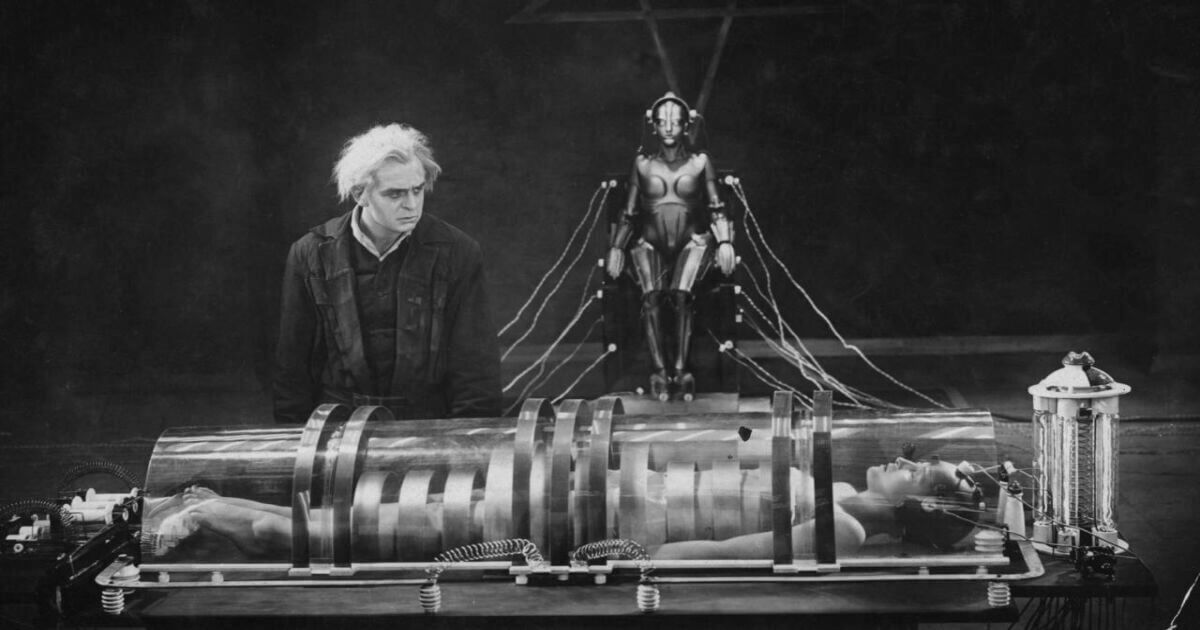

Machine

The world situated above sea level is Earth’s Eden, striking us with its whiteness, modernity, and monumentality. The underground resembles dark, narrow corridors dug by ants between clumps of earth, and this comparison is not coincidental, as the workers, much like the mentioned insects, appear almost identical, with the sole exception being Maria, the counterpart of the ant colony queen. In the eyes of the workers, treated by the owners as mere cogs in the dead machinery, Maria is someone who would be considered a prophet in today’s terms. She proclaims a thesis suggesting that a person will come who will unite the hands (a metaphor for the workers) and the mind (a metaphor for the owners) with the heart, creating a symbiotic human organism (a metaphor for a content society). Alongside the prophet, there usually emerge mystifiers attempting to exploit their social position. In Metropolis, the machine becomes the mystifier, crafted with such precision that it cannot be distinguished from a living being.

The story written by T. von Harbou, Fritz Lang’s longtime spouse, strikes the viewer with its relevance. What seemed like science fiction several decades ago is slowly evolving into everyday reality. Isn’t our lives sometimes dependent on the tones of metallic machinery? Indeed, they are, which leads to the question of how long we will be able to control such machinery? When will the day come when someone somewhere constructs their own “false Maria,” which, unnoticed, will start functioning on equal terms with representatives of the human species?

It’s terrifying that the screenplay’s author became entangled with the ideals of National Socialism a few years after the film’s creation. Does the vision of the world presented in Metropolis sometimes criticize totalitarian systems? Do people clothed in uniform smocks, toiling daily in a murderous labor, not resemble prisoners of concentration camps? Could the message of Metropolis be fundamentally anti-Hitler?

As in most films bearing the mark of “German cinematic expressionism,” the set design is the most captivating aspect. Lang’s film is no exception; the apocalyptic city constructed within the confines of a German studio is simply breathtaking. The modernity of the surroundings around the “New Tower of Babel” and the all-powerful underground machine, which feeds on the toil and sweat of the worker masses, can find their decorative counterparts only in works of Italian monumentalism, akin to Cabiria by Pastrone.

Naïveté

Nevertheless, Metropolis is clearly beginning to lose the spirit of its excellent predecessors (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Nosferatu). Abandoning the fascination with nearly mad characters, relinquishing the dreamlike set designs crafted by surrealism’s creators, it becomes a monumental film, yet somewhat naive at the same time. Naive in its vision of society, in its vision of reconciliation, and ultimately naive due to the abandonment of the “expressionist hero.” This term can only be applied to the creator of the “false Maria,” the demonic Doctor Rotwang.

Although Fritz Lang’s Metropolis is not the most outstanding achievement of German expressionists, it’s a film that has permanently etched itself into the history of cinema. It’s a film whose echo continues to resonate in the realm of popular culture. We encounter it among Asian anime productions, in the music videos of the legendary band Queen, and more recently on the screens of movie theaters in its most complete version (the original was destroyed). While the music videos of the British legend and the animated Metropolis DVDs remain in circulation, the opportunity to admire this giant on the silver screen may repeat itself only after 80 or so years. Thus, all that remains for us is to go to the cinemas and let ourselves be captivated by a 20th-century vision of contemporary times.