How THE CREATOR ‘S FAILURE exposes the CRISIS in contemporary SCIENCE FICTION

Even before the premiere, my moods, as well as those of many critics, were unequivocally positive. It seemed that we would get a piece of solid science fiction with a universal message, but also with a contemporary commentary on the growing concerns related to artificial intelligence. However, what we received on the day of the premiere in no way met our expectations. The Creator disappointed, which is reflected in the box office results – as I write these words, the fate of whether the film will financially recover is still uncertain.

The fundamental problem with Gareth Edwards’ production lies in the meaning of one word – emptiness. Regardless of how visually attractive the film remains (and it is from start to finish), regardless of how skillfully it was shot (kudos for using a single type of camera), my critical integrity does not allow me to see The Creator as anything other than a hollow product. The annoying and at the same time tedious CLICHE that emanates from the screenplay of The Creator is something that cannot be swept under the rug during the reception of the film. My colleague Marcin wrote about it in more detail in the editorial review, and I can only agree with his words. Yes, I agree – it’s a film about artificial intelligence, but it sounds as if it was written by a robot.

I would like to use The Creator as a pretext for a broader look at the genre and the crisis it has been in for quite some time in my opinion. In this regard, The Creator was not just an ordinary creation meant to provide visual oblivion but something that promised to address the surrounding reality. A reality that is dynamically changing, I might add. We are right in the midst of a media crisis, and its demands are expressed through strikes by screenwriters and actors. One of the loudly discussed slogans is the role of artificial intelligence in the creative process. In short, we have let AI onto the playground, and now we are afraid it will take the initiative and push us, the creators, out of the market. And this is not the only area that AI could soon dominate.

The reversed message

There is something surprising and paradoxical in the fact that when James Cameron released one of the most gripping portrayals of the battle between humans and artificial intelligence in 1984, I’m referring to the iconic Terminator, the war against machines was depicted in an extremely catastrophic way, leaving no room for discussion – in the face of AI, we will be at a disadvantage, Cameron suggested. However, this was a time when the threat posed by AI contact was minimal, even illusory, and the audience didn’t really believe in the horror depicted in Terminator, treating it with the appropriate distance for entertainment. Today, however, with the everyday presence of artificial intelligence, partly due to the popularity of ChatGPT, we witness a film where the war against machines unfolds in a completely different manner. In The Creator, artificial intelligence is no longer an ruthless killing machine to be feared. It is human that should be feared.

And here lies the problem. Because following this line of thought, it seems to me that instead of progressing, we are regressing. None of us are prophets of the future. By seeking the problem within ourselves rather than in the creation we bring to life through our blind ingenuity, we deliver a trivial message as if evil is within us. Since it’s an issue that seems unsolvable and challenging to question, the messages conveyed in The Creator ultimately fall into a void. What I expect from this kind of cinema, from contemporary science fiction, is to be ahead of its time, to reach further than paradigms and current discourses. In short, to challenge science, ethics, and our convoluted present. Science fiction cinema, despite its supposedly ambitious and engaging nature, often sells banality. It’s based on overly worn narrative schemes that repeat truisms about our imperfect morality, sounding like messages from fables. These messages themselves are not inherently bad, but what’s bad is that they are the only value these stories offer.

Nineteenth-century science fiction writers had a broader vision

Promoters of the genre, like the mentioned Julius Verne and H.G. Wells, had the characteristic of depicting such bold visions that exceeded their times. It led to a self-fulfilling prophecy phenomenon because the technologies they portrayed gained a prophetic value, serving as ready sources of inspiration for potential creators and scientists. While Verne may not have invented the submarine with his Nautilus, he certainly ignited the imagination of scientists strongly enough that after 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, they desired to relate to his vision (especially since Verne proposed electric propulsion, which was innovative at the time). Although we didn’t get Wells’ time machine from his vision, isn’t it fascinating that already in the 19th century, a writer pondered whether what was only scientifically analyzed decades later would be possible?

It is precisely the contemplation of the human condition, the intricate morality, as well as vigilant observation of contemporary society, culture, science, and technology while anticipating the possible consequences of civilization’s development that fascinates me the most in science fiction. This is also a characteristic sorely lacking in today’s science fiction films.

“Emptiness.” This word, which I will mention again, seems to be the best way to describe the problem. Great visions, perfectly designed, exquisitely crafted stylistically, yet not offering much beneath the surface of spectacle. Mad Max: Fury Road, Blade Runner 2049, or Arrival, are films that are often mentioned in lists of the best SF films of recent years. They are also films that, regardless of how they look and captivate the audience, get stuck in screenplay doldrums, leading the story to exceptionally unoriginal conclusions. They exhibit something that I would call the need for creators to stay within the safe zone of tried-and-true formulas. However, I am waiting for a breakthrough beyond this comfort zone.

The last significant breakthrough

I advocate the claim that a turning point for the genre was the year 1999 and the release of The Matrix. It’s a film that, beneath its stunning visual layer, hid plenty of hidden messages and intriguing cultural contexts that were revealed only during subsequent viewings. It was also a film that went beyond the boundaries of its vision. How so? It was connected to the technological concerns that were growing at the turn of the new millennium—virtual reality, artificial intelligence, the anticipation of a technocratic society. Again, following in the footsteps of Terminator, it used hyperbole to instill fear in the viewer. It sent a clear warning signal in a loud and suggestive manner, all while using universal messages.

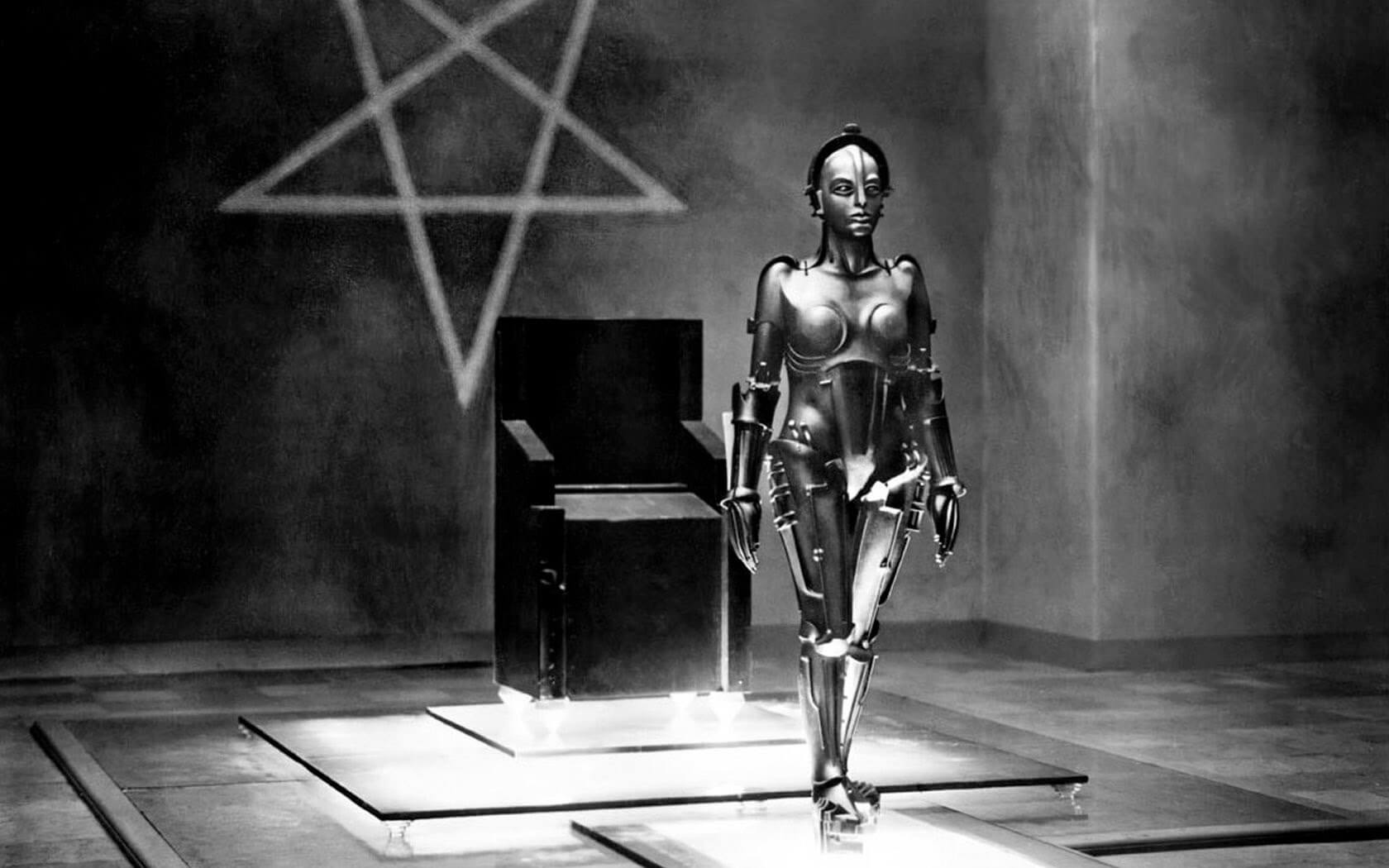

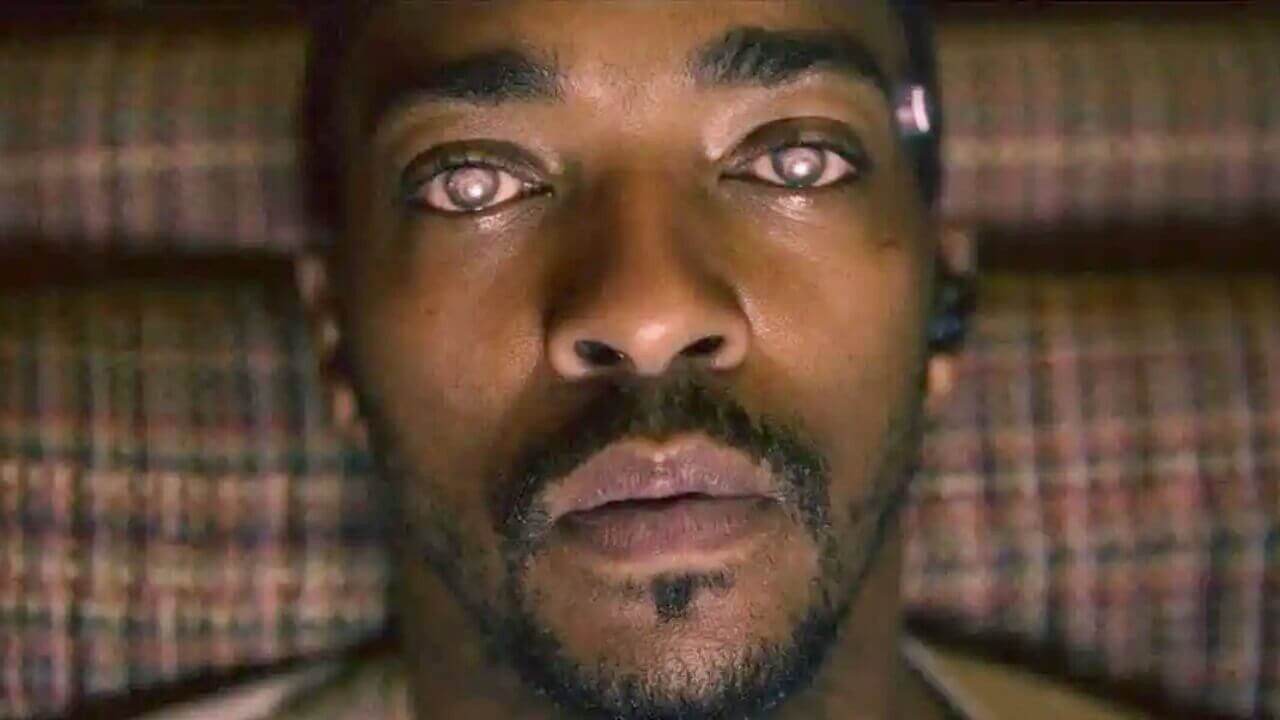

In the new millennium, aside from a few innovative and daring visions, such as the masterful Children of Men, the genre generally reached a dead end. In the nineteenth century, stories were told about technology that didn’t exist, so there was fear of it. From Metropolis to 2001: A Space Odyssey, to Star Trek, to The Matrix, that fear and curiosity were very much alive in us. Today, stories are told about technology that does exist. People generally want to control, reconcile with, and understand it in their visions—without worrying much about the future. This was the basis for popular SF series like Westworld or Raised by Wolves. And that’s what ultimately led to their downfall. An attractive starting point turned out to be insufficient to sustain a story for long.

Contrastingly, the creators of Black Mirror took a different approach, aiming for each episode to be different but always based on the principle of instilling technological horror. It paid off, as the series was a success, with many episodes containing more innovative thinking than all the genre films released in a given year. However, they, too, seem to have run out of ideas, as evident in the last season, which clearly resorted to, if not exhausted, the horror stylistic trope. Some perceive it as a freshness syndrome, but I view it as a sign of creative stagnation for a series that once stimulated the imagination.

It took me just a few minutes into The Creator to understand what I was dealing with. Once again, I fell for the enticing hard SF costume. I grew bored with the film before it even properly began. When a child appeared on screen, seemingly intended to evoke sympathy for an artificial entity, I knew with a fair degree of certainty that the creators of The Creator were not interested in whether AI would want to dominate us. They preferred to silence our moods in the name of the message of irrational tolerance and reducing the human face to zero-one code. I perceive this as cheap manipulation of emotions.

Dreams

I ponder the prospects that technology brings, whether we can overcome the barrier of diseases, aging, and death. I think about a new definition of humanity, with God dead but still alive within us, in the form of a mighty force capable of subduing nature. Consequently, I think about a new species of earthly beings, artificial intelligence, which may soon supplant homo sapiens, just as homo sapiens displaced Neanderthals (as suggested in The Creator, which was the only interesting aspect of the film). I also wonder whether technology will hinder or help us in saving the natural environment and reconciling with it.

I think about the future paths of human territorial expansion, which may extend deep into the Earth and certainly into space, the deep cosmos. Again, there’s a lack of something that goes beyond well-trodden paths because it’s hard to use such a term to describe something like The Martian, which was written based on Robinson Crusoe’s adventures. Finally, I contemplate the cultural changes we are currently witnessing, which may be amplified due to our interaction with technology and the development of media. New customs and traditions may emerge as a result, shaped by a clear trend towards secularization or, if you prefer, an ecumenical, New Age approach to spirituality. The face of war is also changing before our eyes, and it’s worth remembering that in the context of science fiction.

Science fiction has often heralded the end of the world, but none of those predictions came true. However, in some way, the end of the world, the old world, has happened, and it’s time to wake up in the new one.