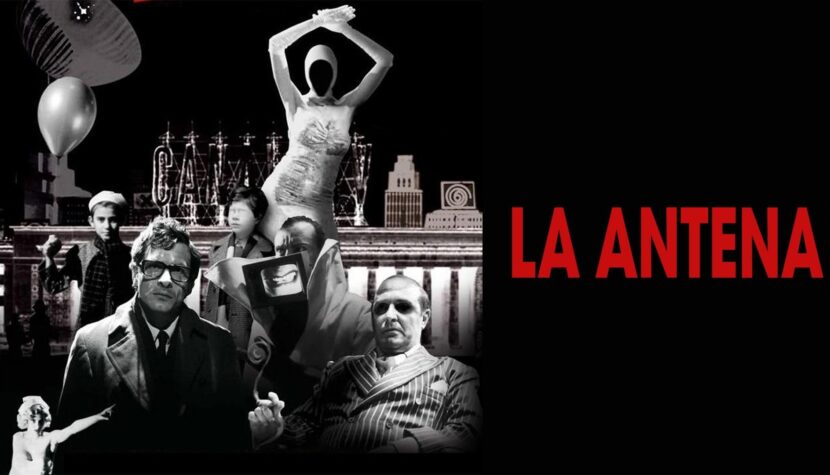

THE AERIAL. Dark and unsettling science fiction

Additionally, the film is black and white and silent, though not entirely.

Esteban Sapir‘s The Aerial consists of an exceptionally strange combination of retro-futurism and legend. The media is ruled solely by the despotic Mr. TV (Alejandro Urdapilleta). He is the owner of the only available television station, where the biggest attraction is the broadcasts of the Voice – a mysterious woman (Florencia Raggi), who probably is not only able to speak but also beautifully sings, providing entertainment to the society. As an addition to the media message (and the only food in the film altogether) are television cookies with the hypnotizing station logo on top. By providing people with media bread and circuses, Mr. TV controls their way of seeing the world.

To the extent that the lack of their own voice doesn’t bother them. They’ve become accustomed to it, although they had it twenty years ago. When the evil dictator wants to expand his influence on the inhabitants, he decides to enhance the transmission of the singing woman’s voice. He connects her to equipment in the shape of a swastika. The initial tests show that its unskilled programming can even kill remotely. But Mr. TV doesn’t want blood, just control. The equipment is supposed to spread the voice throughout the city, to incapacitate and completely subdue the society. In order to prevent this, a TV repairman (Rafael Ferro) along with his family and the son of the woman with the voice (who inherited this gift from her) set off to an abandoned transmission tower topped with the titular antenna. There, the boy gets connected to a machine shaped like… the Star of David, to thwart Mr. TV’s plans.

The Aerial combines several elements. The events presented form a dark fairy tale, where magical elements are not lacking. It’s unclear how the voice was taken from the town’s inhabitants or why it doesn’t affect one woman and her child. The boy is blind and has undeveloped eyelids, and Mr. TV sends paper glasses with drawn eyes in an envelope, which serve as a fully functional eye prosthesis. The character from the fairy tale also resembles the deformed chauffeur of the dictator, the Mouse-Man. Formally, The Aerial is a homage to silent films – especially film noir, German expressionism, and the works of Georges Méliès. This is evident both in the appearance of a huge moon with a cigar in its mouth, and in the depiction of a developed city reminiscent of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. A keen viewer will notice many references and quotes in the city’s appearance and composition of frames. Although not all of these techniques serve a purpose (some are just decorative), it looks very interesting and simply enjoyable to watch.

The setting is the City without Voice, and the characters communicate through gestures and lip reading. Subtitles are provided, but not in the form of ornamental text boards, as in the twenties. The words are placed to correspond with the characters’ body language and the mood of the scene. A scream is marked with appropriate actor expression and larger letters, and a rapid series from a rifle spreads sound-mimicking “rat-a-tat-tat!” across the screen. Such use of text in scenes makes every conversation much more dynamic than its meaning would suggest. This is more reminiscent of comic book dialogue bubbles than panels in classic silent cinema. The association with a graphic narrative is very apt because the visual aspect is significant in The Aerial.

The Aerial is a formal experiment with a fairly simple, fairy-tale plot and imaginative appearance. Hundreds of filmmakers have tackled the appropriation of society’s voice, its dumbing down by mass media, like David Cronenberg in Videodrome, and the influence of junk food on the brain was already discussed in the niche Decoder by Muscha. However, the reference to the Holocaust used in Antenna changes the whole tone to something much darker and more depressing.