THE 400 BLOWS. François Truffaut’s Masterpiece Explained

And despite the distress caused by some newspapers printing various foolish things, I absolutely do not regret making this film. I knew it would cause you a lot of worries, but I don’t care: since Bazin’s death, I no longer have parents.

This is how, in an exceptionally bitter manner, François Truffaut began a letter to his father, written even before the French premiere of The 400 Blows at the end of May 1959. The tense relations with his parents completely fell apart after the film hit the big screens. The mother’s family practically disowned François. Even years later, at his mother’s funeral in August 1968, no one spoke to him. The director’s mother never saw her two granddaughters in her lifetime. What did Truffaut present in The 400 Blows that so shocked the relatives of the French director?

The simplest, yet also the most accurate answer, is the truth. Truffaut based the script for The 400 Blows largely on authentic events from his own biography. The constant arguments at home, the ongoing tension between the protagonist and his mother, copying Balzac, escapes to the streets of Paris, skipping school with a friend, outings to the cinema with money meant for food, finally the theft of a typewriter and being sent to a center for juvenile delinquents—all this, along with many other details, the director drew from his own childhood, condensing it into seven days of action and slightly modifying it for the screenplay and the associated film drama. Naturally, names were also changed—Truffaut himself hid behind the mask of Antoine Doinel, whose last name he most likely borrowed from a close collaborator of Jean Renoir. He changed his parents from Roland and Janine to Julien and Gilberte, altering their interests from mountain tourism to car racing (the father eternally seeking the Michelin guide) and beauty (the mother constantly looking at herself in the mirror). However, he did not change their attitude toward the child, summarized by Truffaut in the quoted letter with these words: Mom hated me so much that for a while it seemed to me that she was not my real mother. No, I wasn’t actually an abused child; I was simply not treated at all. I felt unloved and—since I lived with you—unnecessary.

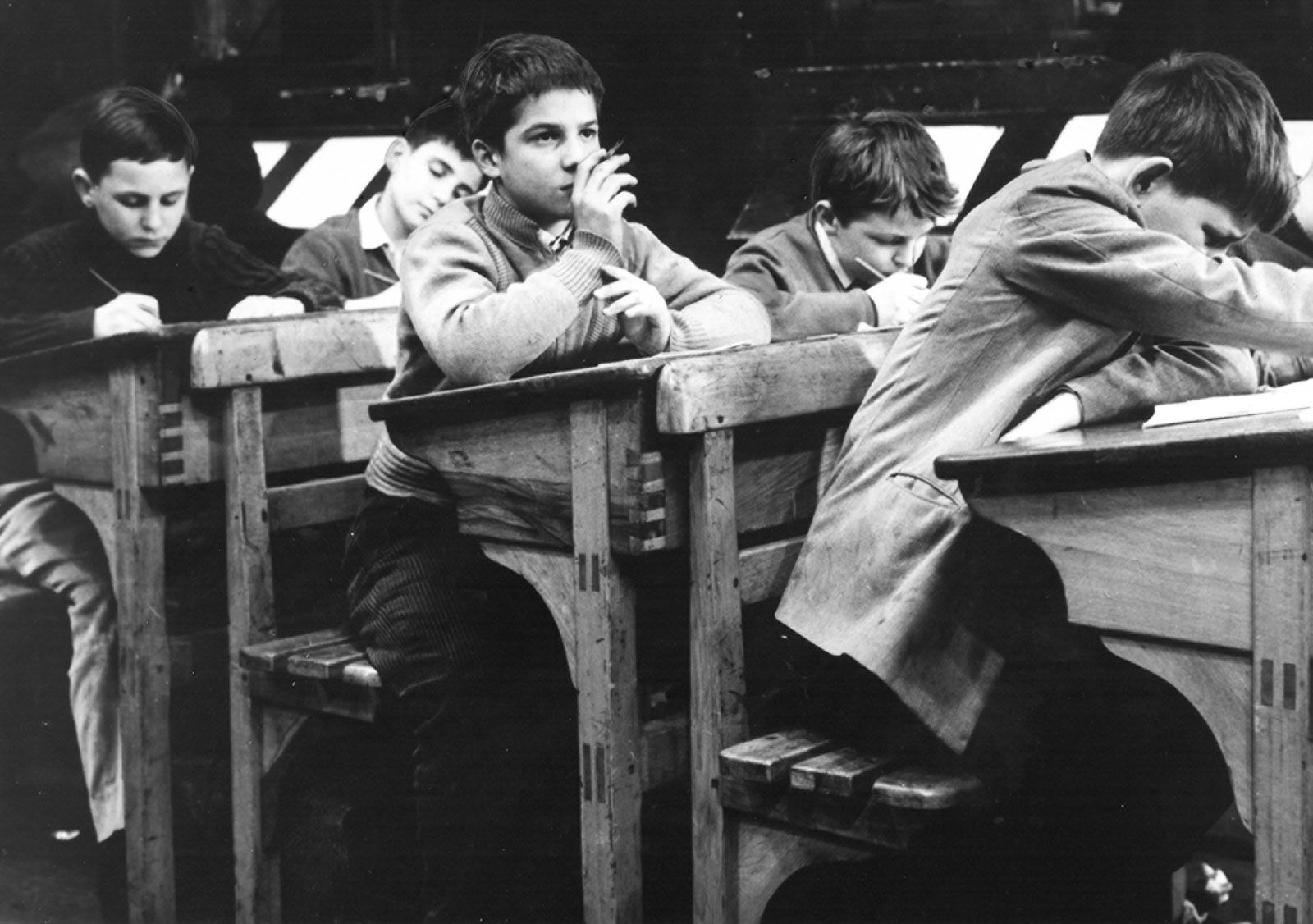

Even in this short excerpt from the letter, it is noticeable how important the relationship with his mother was for young François. Of course, it had its impact on the shape of The 400 Blows. Tadeusz Lubelski, citing Anne Gillain’s research, even states that it is the mother who constitutes the hidden spring of the entire chain of events, gradually leading to the hero’s increasing loneliness and isolation. Antoine’s constant troubles begin in the very first scene of the film, which takes place in the school the protagonist attends. A picture depicting a scantily clad woman—a classic pin-up girl—wanders around the classroom. The boys glance at it, chuckle under their breath, and pass the picture along. Eventually, the photograph reaches Antoine, who is the only one to hold on to it longer. He starts drawing a mustache on the woman in the picture, but during the act, he is caught by the teacher and punished. An innocent, quite funny scene. However, Lubelski and Gillain interpret it in a surprising, exceptionally interesting way—according to the researchers, Antoine, by altering the picture, unconsciously “takes revenge” on femininity. The only representative of femininity in Antoine’s life is his mother—symbolically, the protagonist thus “takes revenge” on her, thereby exposing himself to punishment from the puritanical society, represented by the exceptionally strict French teacher.

But why does Antoine seek revenge on his mother? The answer comes quickly. Just a few scenes later, the audience meets the protagonist’s mother—a rude, demanding woman focused solely on herself and her appearance (less than a minute after entering the apartment—assuming the scene unfolds in real time—she starts admiring herself in the mirror, smoothing her face with satisfaction; Truffaut draws the viewer’s attention to this small but telling scene by filming it in close-up). To Antoine’s optimistic “Good evening, Mom,” the woman grumbles something under her breath, manifesting her negative attitude towards her son. Immediately afterward, she starts changing clothes in his presence. She removes her stockings, exposing her legs—she doesn’t consider his maturing masculinity at all. Then, as if that weren’t enough, she scolds her firstborn about the flour and sends him to the nearby store. The viewer quickly starts to understand little Antoine.

The mother’s return home is significant for yet another reason—it interrupts Antoine from completing the homework the teacher imposed on him as punishment. Because of his mother, Doinel is unable to prepare for class, which directly influences the decision he makes with his friend the next morning—to skip school. The woman is thus partly responsible for her son’s truancy. During this time, Antoine catches her in the street in the arms of her lover! This situation further complicates the relationship between mother and son, introducing an element of awkward, shameful secrecy into their dynamic.

The truancy, for which the mother is partly responsible, forces the protagonist to come up with an excuse. First, Antoine tries to forge his mother’s handwriting, using a template borrowed from René, but his efforts come to nothing—his father’s return home prevents him from completing the task. Finally, unable to find a better excuse, Doinel tells the teacher the next day that his absence was due to his mother’s death. As Lubelski notes, The verbal death is probably, on the one hand, his revenge, and on the other, an unconscious naming of the mother’s real attitude toward the son: in a psychological dimension, it is as if she is indeed absent.

However, lies have short legs, especially such perfidious ones. It quickly becomes apparent that Antoine lied to the teacher, for which the boy faces an exceptionally harsh punishment—his frustrated father slaps him twice in the face in front of the entire class. Humiliated, first by the truancy and second by the false excuse (both of which are inextricably linked to the mother!), young Doinel decides to run away from home. After this story, I can’t live with my parents anymore, he confides to his best friend, who offers him a place to stay at his uncle’s print shop.

The next day, the mother visits her son at school. She takes him from his English lesson home, where she surrounds young Doinel with unexpected tenderness, surprising both him and the audience. This tenderness, however, is tinged with calculation, according to Lubelski: The mother may fear that the son will reveal her secret to the father (after his discovery), so she tries to bribe Antoine with affection. Is this really the case? It’s hard to say with absolute certainty. It’s possible that in the protagonist’s mother, concerned about his overnight absence, his “verbal death,” and the rather telling and very mature letter she received from him, an authentic love for her only child emerges for a few scenes—a maternal instinct that had been pushed to the background until now.

It is noticeable that young Antoine, despite being treated by his mother in such a way, is clearly fascinated by her. This is confirmed by the scene preceding the mother’s return home—young Doinel browses through her cosmetics, accompanied by the cheerful leitmotif of The 400 Blows (composed by Jean Constantin), suggesting the protagonist’s unmistakably positive emotions.

Where does this unequivocally negative, if not “hateful,” attitude of the mother towards her son come from? What is its source? Truffaut provides an answer, very cleverly, in the scene of the “healthiest” conversation Mrs. Doinel has with Antoine. The woman tells her son about her youth, which includes not completing her studies. She associates Antoine’s birth with her own failures and unfulfilled ambitions, treating her firstborn as a kind of “mistake of youth”—a slip-up that halted her development and prevented her self-realization.

Later that same day, in a good mood, the woman makes her son a deal: if his next essay receives the teacher’s approval and a positive grade, he will get 1,000 francs. In this way, the protagonist’s mother unwittingly, but nevertheless, once again lands her son in trouble. Trying to write the best paper possible, Doinel resorts to plagiarism, basing his essay about his grandfather’s death on an extensive paraphrase of the ending of Honoré de Balzac’s The Quest of the Absolute. For this, he faces another severe punishment at school (suspension), which influences Antoine’s decision to run away from home again.

Although at first glance it may seem that The 400 Blows has a more episodic than linear structure, a closer examination reveals that all the episodes form a logical cause-and-effect chain, whose main organizer is the mother. It is she who, largely unknowingly, brings more and more trouble to the innocent Antoine. Even the last incident, decisive for Doinel’s future—the theft of the typewriter from his father’s office—should be linked to the mother of the protagonist. Tadeusz Lubelski, referring to the research of Anne Gillain and D.W. Winnicott (a psychoanalyst and pediatrician), states that theft by a child (…) is always an act of hope to regain the love they feel deprived of. The juvenile thief does not need the object he steals; in fact, without knowing it, he is looking for a specific person, the mother, to rebuild contact with her.

The father, or rather the stepfather of the protagonist, is a counterpoint to the mother. The viewer learns explicitly that Mr. Doinel has no blood relation to the protagonist very late, only in the scene where the mother talks with the judge—a segment that precedes the transfer of the setting (and Antoine himself) to a juvenile detention center. However, earlier in the dialogue, there are some hints suggesting this situation. In this context, attention should be paid particularly to the scene of the quarrel after the mother returns home at night. Antoine, and with him the viewer, listens to a sharp argument during which Julien Doinel says the significant words: I gave him a name and feed him! Does the protagonist suspect the truth? Truffaut does not provide a clear answer to this question. However, he suggests, through a long close-up on the protagonist’s face during the off-camera argument, that the boy understands much more than it might seem.

Julien Doinel seems to be a much more positive character than his wife. The viewer first encounters him when Antoine returns to the apartment from the flour errand—he meets his stepfather in the stairwell. The man and the boy climb the stairs together. The former even allows himself a little joke—he throws a handful of flour on his stepson’s face, which greatly amuses Antoine. However, the atmosphere soon deteriorates because Mrs. Doinel, who is not in a joking mood, is already waiting for the protagonists in the apartment.

In the best moments, which are not lacking throughout the film (climbing the stairwell, the conversation in the kitchen, a family outing to the cinema), the stepfather can be almost a rock for Antoine. A person thanks to whom home is bearable for more than a few minutes—it is with him, rather than with his mother, that the protagonist sometimes shares moments of understanding. In these priceless moments for the protagonist, Julien Doinel begins to resemble Mr. Hulot from Jacques Tati’s series of comedies. This resemblance is not only physical (although the similarity is undeniable), but also in his friendly, somewhat carefree attitude toward life (fascination with car racing, naivety regarding his wife’s affairs) and a childlike tendency to joke about everything and everyone.

However, Julien is not without flaws. In moments of anger, he does not hesitate to raise his hand against Antoine. His impulsiveness is particularly evident in two scenes: the intervention of the protagonist’s parents at school and the incident caused by the “fire” at the shrine dedicated to Balzac. In the first, the stepfather humiliates his stepson in front of the entire class by slapping him in the face. In the second, instead of helping the mother contain the fire, he starts yelling at young Doinel and shakes him violently. Robert Ingram notes that his carefree behavior starkly contrasts, which completely confuses Antoine, with sudden outbursts of brutality.

After analyzing the mother and stepfather’s characters, their relationship with the son, and their influence on the plot’s development, it is worth dedicating a little space to the protagonist himself. Who is Antoine Doinel in The 400 Blows? Is he just a recreation of François Truffaut’s childhood, vividly portrayed by the young Jean-Pierre Léaud? Or is he something more? If so, who? To answer these questions, it is worth looking at the main character of Truffaut’s debut from three different angles.