QEDA. A science fiction story about climate disaster and time travel

In QEDA, when an ecological catastrophe strikes Earth, the Danish government sends an agent back in time. His mission is to locate a researcher whose discovery could save the world.

It is the year 2095. Following a climate disaster, global sea levels have risen dramatically, causing enormous damage: continents are flooded, freshwater is contaminated, and plant and animal species are dying off. To prevent further catastrophe, time travel technology has been developed and is used by special agents under the codename QEDA (Quantum Entangled Divided Agent). According to the principles of quantum mechanics, each agent is split into two entities: one makes the jump back in time, while the other remains in the present, both remaining connected. The head of Danish intelligence, Fang Rung, sends his other half, Gordon Thomas, to the year 2017 to find geneticist Mona Lindkvist, whose lost research could save the world from apocalypse. Rung loses contact with Thomas and is forced to travel to the past himself, risking inevitable changes to the future.

“QEDA” is the feature-length fiction debut of Danish director Max Kestner, known for his documentary films (such as “Nede på jorden” (2002), “Drømme i København” (2009), “I Am Fiction” (2012), and “Amateurs in Space” (2016)). “The core philosophical idea of “QEDA” is that in our daily lives we are time agents who can change the future, but we can only make changes here and now,” Kestner explained in an interview with Soundvenue.com. The film hit Danish cinemas in November 2017 and won the Méliès d’Argent at the Trieste Science Fiction Festival the following year, along with ten nominations for the Robert Award, Denmark’s top film prize. Despite this success, “QEDA” was met with a lukewarm response from critics; it was said that the acclaimed documentarian struggled with the narrative form, something Kestner himself admitted in an interview with EkkoFilm: “I didn’t know what to bring [to the film] as a director.”

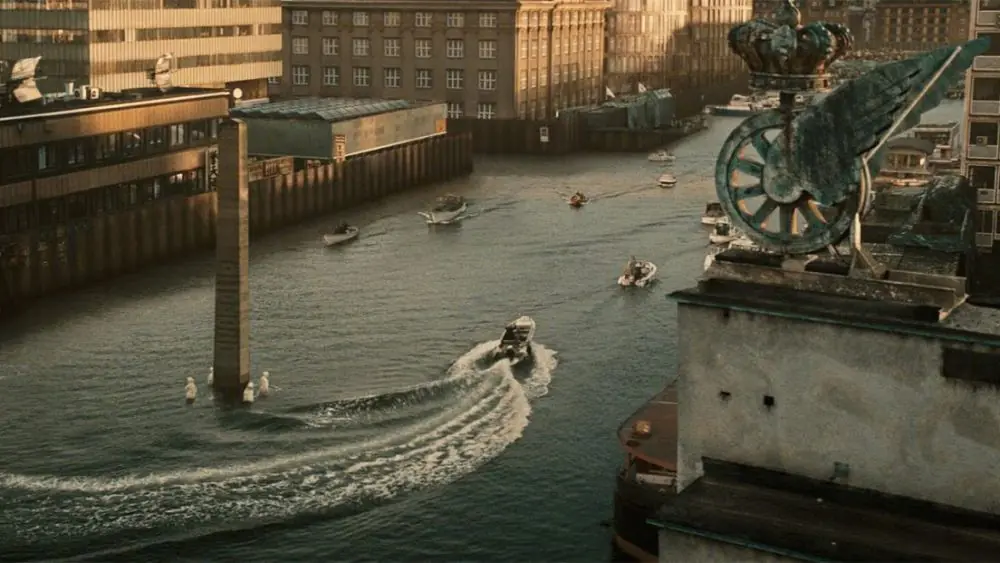

If the creator himself cannot defend his work, it becomes even harder for the audience to do so. Nevertheless, let’s try, starting with the strengths of “QEDA”, because despite its undeniable flaws, the film has a number of redeeming qualities. The first thing that stands out to viewers is the visual style: the cold, dark tones of the cinematography convincingly depict a bleak post-apocalyptic future (dead trees, deteriorated buildings, and partially submerged Copenhagen, resembling a dystopian Venice on the Ganges). The vision of a post-ecological catastrophe planet recalls Lars von Trier’s “The Element of Crime” (1984)—it is equally evocative and resonates all the more today, as disturbing climate changes unfold before our eyes. Max Kestner may say he didn’t know what to add to the film, but he clearly knew how to create an atmosphere of a world deprived of all hope.

However, beneath the intriguing visuals lies little substance. “QEDA”’s main flaw is the screenplay (likely inspired by Terry Gilliam’s “12 Monkeys” (1995)), which neither deeply explores the post-apocalyptic world nor fleshes out its characters. It’s hard to feel invested in the fate of Rung/Thomas and Mona because they themselves seem indifferent to everything. The quantum agent attempts to change the fate of the world, but he does so half-heartedly, as if he doesn’t believe in his mission’s success. Another weakness of the story emerges here: the reasons for Rung/Thomas’s journey to 2017 don’t make much sense, as reconstructing genetic code seems easier and less risky than time travel. The intrusive voice-over also undermines the “show, don’t tell” principle. Yet, despite these shortcomings, “QEDA” is worth watching, if only for the scenes of destruction, which, in the context of recent floods, feel unsettlingly relevant.