12 MONKEYS explained. It’s not sci-fi movie for Christ’s sake!

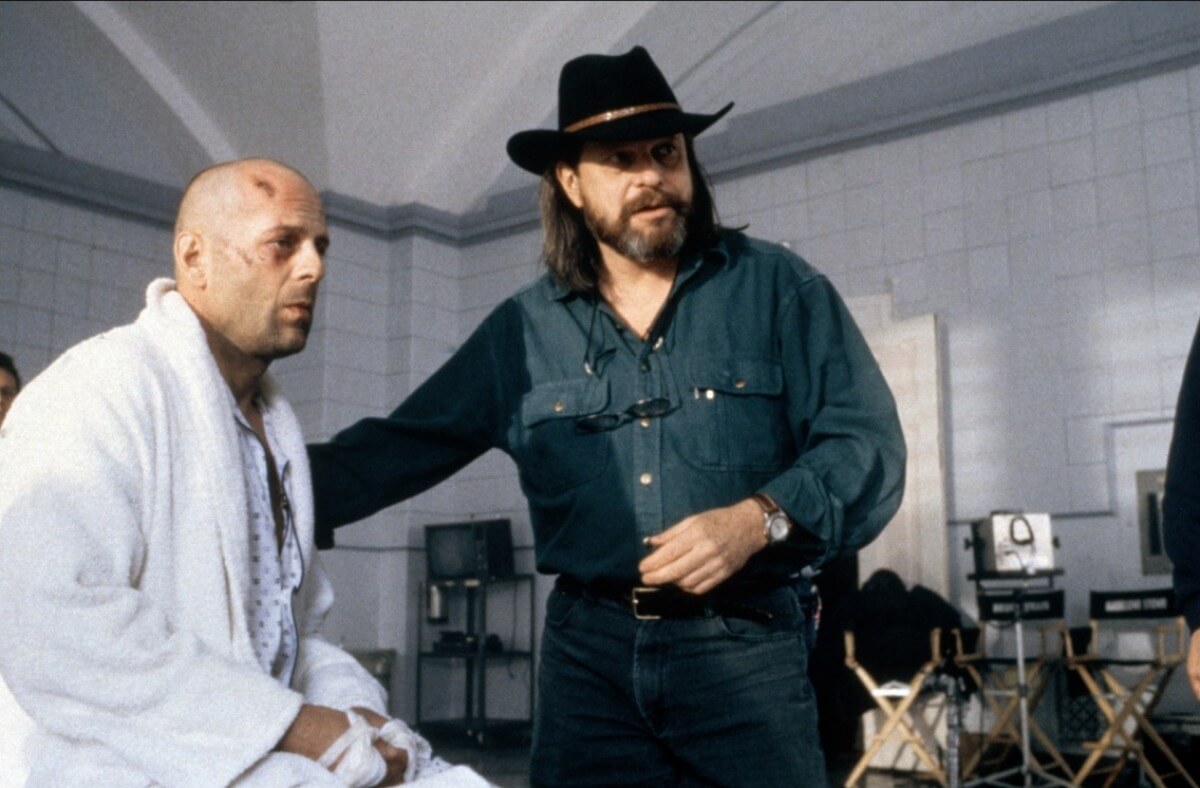

Terry Gilliam likes to surprise. Not everyone has to like his visually stunning cinematic spectacles, but there is probably no one that would deny him creativity and a taste for surreal images straight from a paranoid dream. His cinematographic feeries ranging from such extreme achievements as The Adventures of Baron Munchausen to the semi-commercial Fisher King, from the Orwellian Brazil to the narcotic visions of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas cause the viewer to have multicolored nystagmus, and sometimes serious doubts about the director’s mental health.

Introduction

So it’s no surprise that he started out as a pillar of the timeless Monty Python group. All the more so we would not expect of him a mercantile science fiction production, which “12 Monkeys” is commonly considered to be. The first encounter with this seemingly unusual picture by Gilliam leaves one’s memory with a certain astonishment with the nature of the film and the subject matter with which the director faced: the apocalypse, the destruction of the human race, a deadly virus and time travel. At first glance, this looks like a post-Fisher King process of commercializing Python’s work. I’d be lying if I didn’t admit that I received 12 Monkeys in a similar way when I first sat in the cinema in the 90s. Gilliam’s work seemed to me then a very efficient, intricate, visually stunning, but only entertainment. Repeated years later, however, I discovered nuances that are usually overlooked or quickly forgotten after the first viewing.

The year is 2035, humanity has gone underground after a catastrophic terrorist attack by the Army of the 12 Monkeys, which spread a deadly virus on the surface that wipes out 99% of the population. The remnants live like rats in the sewers, and the penitentiary system sends recalcitrant prisoners called “volunteers” to study the remains of life on the surface of the earth, which is now ruled, as millions of years ago, by animals. James Cole (Bruce Willis) is one of the “volunteers” falling victim to another scientific program that aims to repopulate the Earth. The technology of the future allows you to travel in time, and Cole’s task is to find the pure form of the virus in the past, in 1996, when the plague began to take its toll. The found virus will make it possible to prepare a vaccine. However, Cole accidentally lands in 1990…

Isn’t it the perfect starting point for a good scifi movie? Sensational plot, time paradoxes and Bruce Willis chased by demons of the past (future?). This is the first moment in which Gilliam knowingly winks at the viewer, taking advantage of the wide audience’s habituation to the conventions of the science fiction genre and the lack of desire to explore the plot and meaning of the images seen due to mental laziness. So let’s take a closer look at them.

A Dream

The central element around which the action unfolds is a dream from the past, a scene from Cole’s childhood that has forever stuck in his memory and which Gilliam – the director opens the film. The scene begins with a close-up of the eyes of a few-year-old boy, through which we see a long-haired man wearing a Hawaiian shirt falling down in the airport lobby. A distraught woman in a red dress is kneeling over the man. We see this scene from the point of view of a boy standing a few meters behind them. After this sequence, we see Cole waking up in the future (2035); he is a sixth-grade socialization prisoner. The hero’s dream plays an extremely important role here, because it will be repeated several times throughout the course of the plot, each time revealing more and more details to us.

|  |

Year 2035

Cole is chosen to “volunteer” to the surface where the plague is still raging and animals rule the world. Its purpose is to collect samples for laboratory tests. After successfully completing the mission, Cole faces the commission and learns that if he decides to take part in the next stage of the experiment, he will receive a reward in the form of pardon. This time, however, they are to send him nearly 40 years into the past (1996) to get the original form of a deadly virus. Unfortunately, the time machine is imperfect…

Year 1999

Thanks to a machine glitch, James Cole travels back to 1990, is mistaken for a madman and placed first in a detention center (where he meets Dr. Kathryn Reilly, played by Madeleine Stowe), and then in a mental institution. While still in custody, one of the officers mentions that the policemen stopped Cole parading around in a foil raincoat and raving about the virus. Doesn’t his funny clothes remind you of something?

|  |

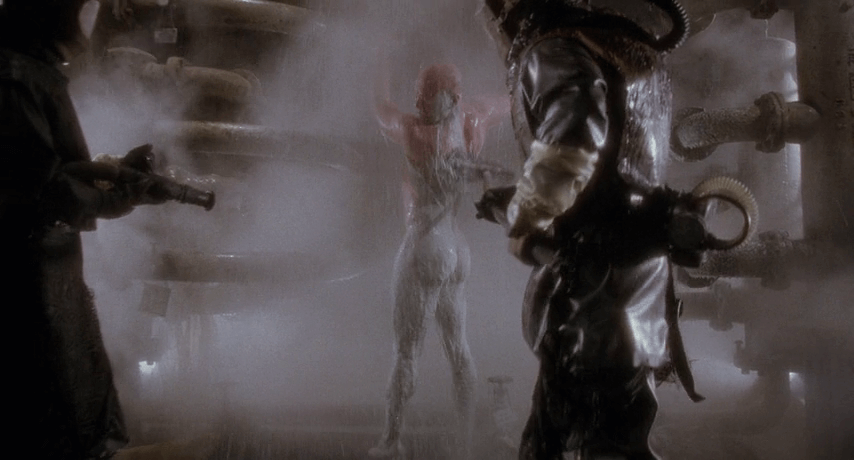

Before being admitted to the ward, we witness another “coincidence”: the hospital’s “hygienic” procedure (shower) is deceptively similar to that from the distant 2035, when Cole returns from a successful mission. Two guards are involved in both situations; even the arrangement of James’ hands is similar. Another coincidence?

|  |

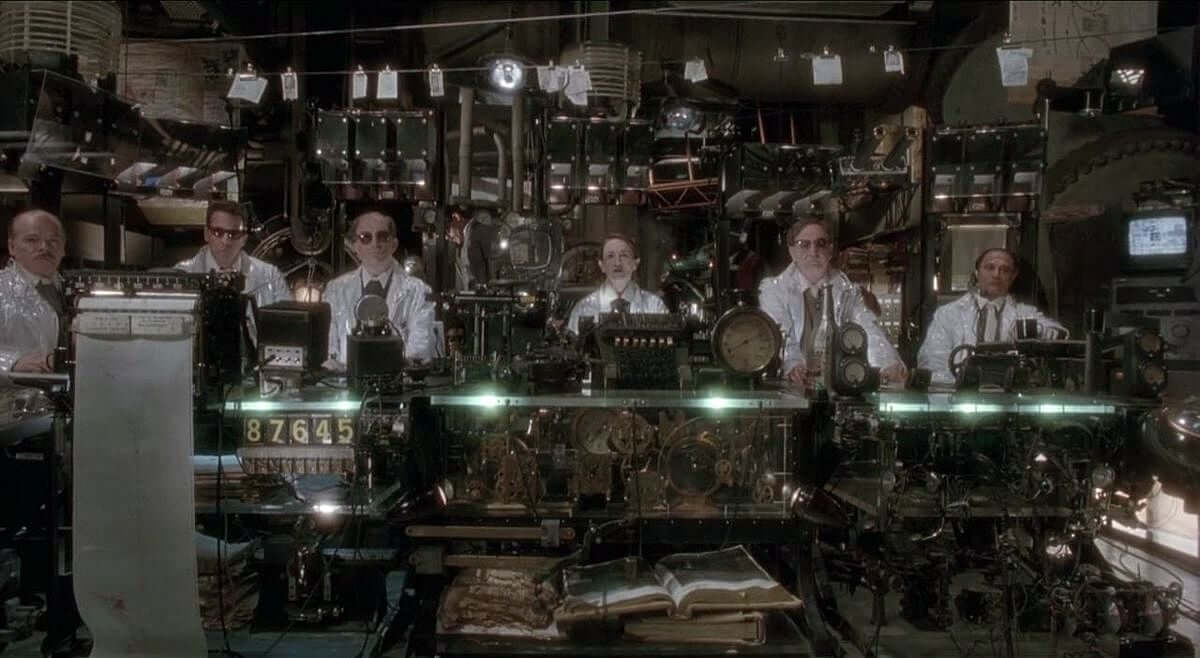

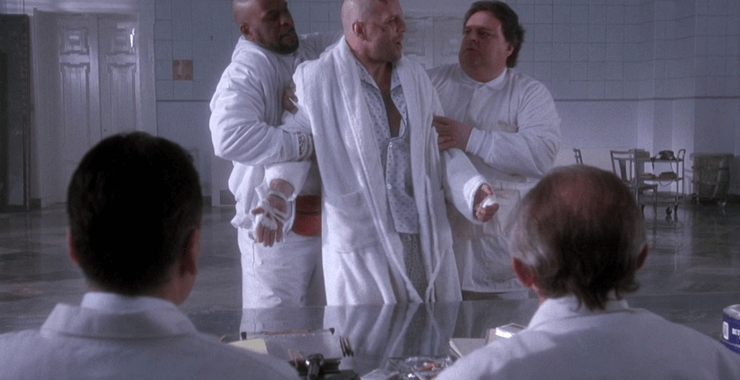

While in the ward, Cole meets Jeffrey Goins (Oscar nominated Brad Pitt), who later enables him to escape from the hospital. He also appears before the medical board. Here is another surprising conclusion: the medical commission, with its character and approach to the patient, resembles the disciplinary commission from 2035. There is no doubt that, except for the grotesque futuristic staffage and disguises, it is an almost identical body. The number of people (six) and composition (one woman and five men) are correct. Also noteworthy are the quasi-medical aprons of the commission members from 2035.

|  |

Also, the hospital guards from both “eras” behave like twins, and even their race and alignment match. Why?

|  |

Jeffrey (one of the best Brad Pitt’s roles), the more eccentric than crazy son of a brilliant father, Dr. Goins (Christopher Plummer) is the catalyst for key (literally and figuratively) events in the ward. He enables Cole to escape by delivering the key to the door and distracting the guards. The escape fails, however, and James, chained and sedated, ends up in solitary confinement. He also wakes up in solitary confinement, only in 2035…

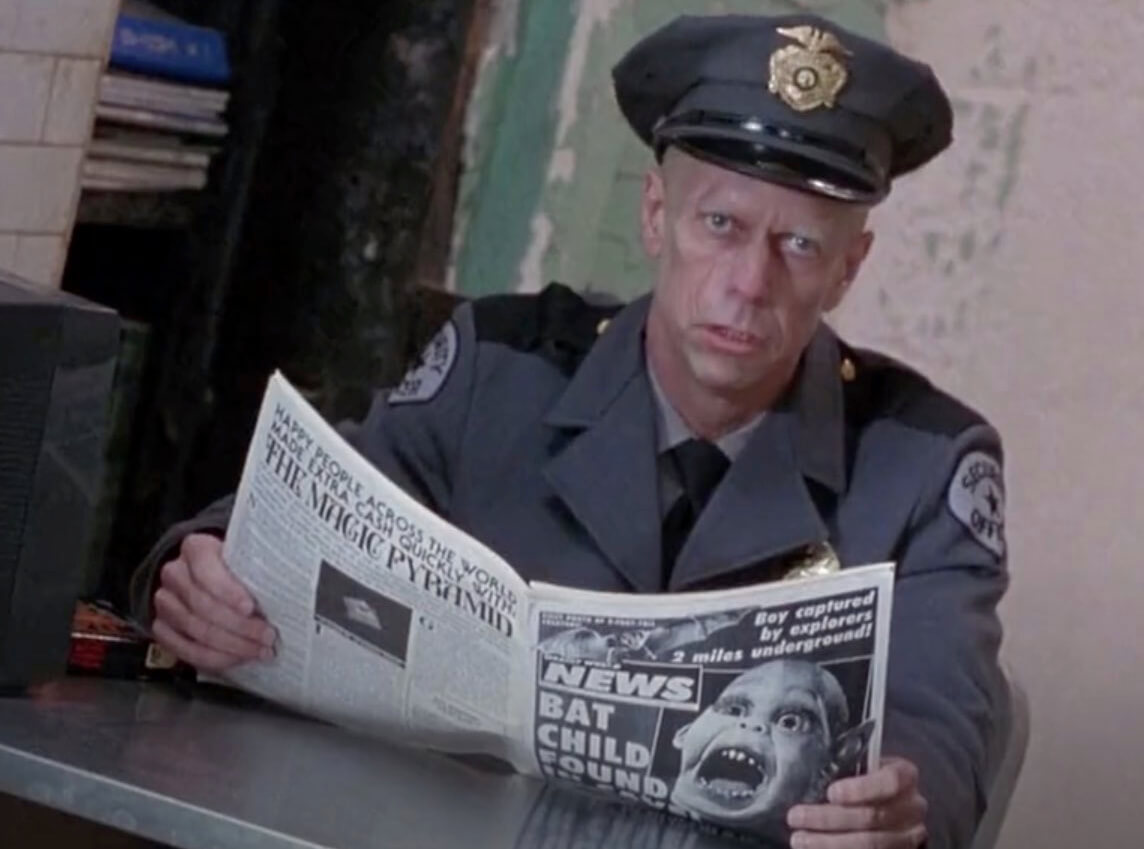

But before that happens, there are two significant events that are worth mentioning here, because they will be crucial in reading the subtext that Gilliam is trying to sneak into the viewer. After escaping from the unit, Cole finds himself in the elevator hall guarded by a tabloid reading policeman (on the cover a photograph of a bat child) who shows him the right elevator (one of them is broken). When Cole looks at him for the first time, the camera shows us a man confusingly similar to the prison guard from the year 2035; when he looks at him a second time, it’s a completely different person.

|  |

Getting off the elevator, the hero ends up in an office where one of the patients is undergoing a CT scan. Nothing surprising in the hospital, but for Cole the sight will prove to be extremely significant, to which I will return in a moment.

Year 2035

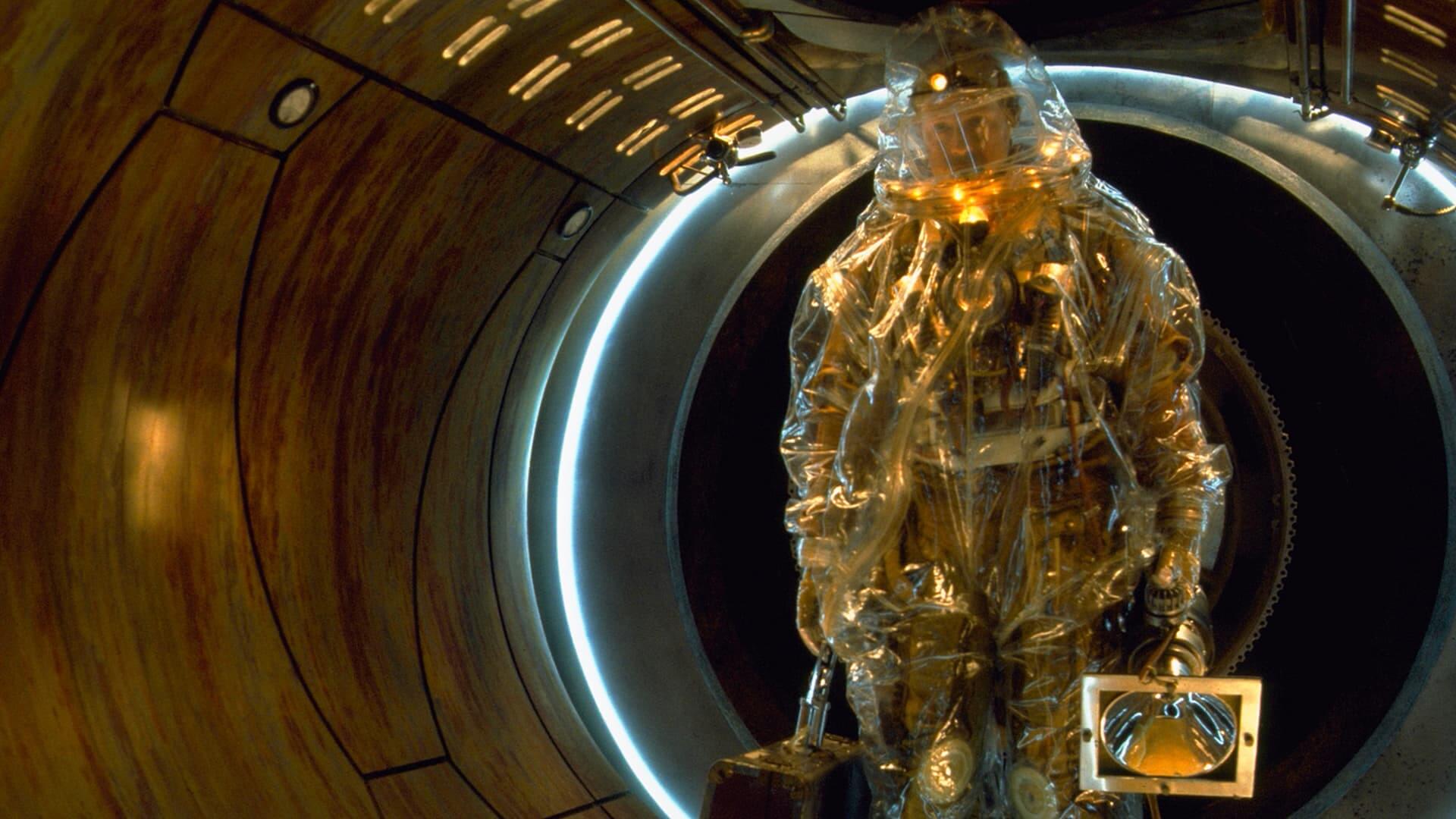

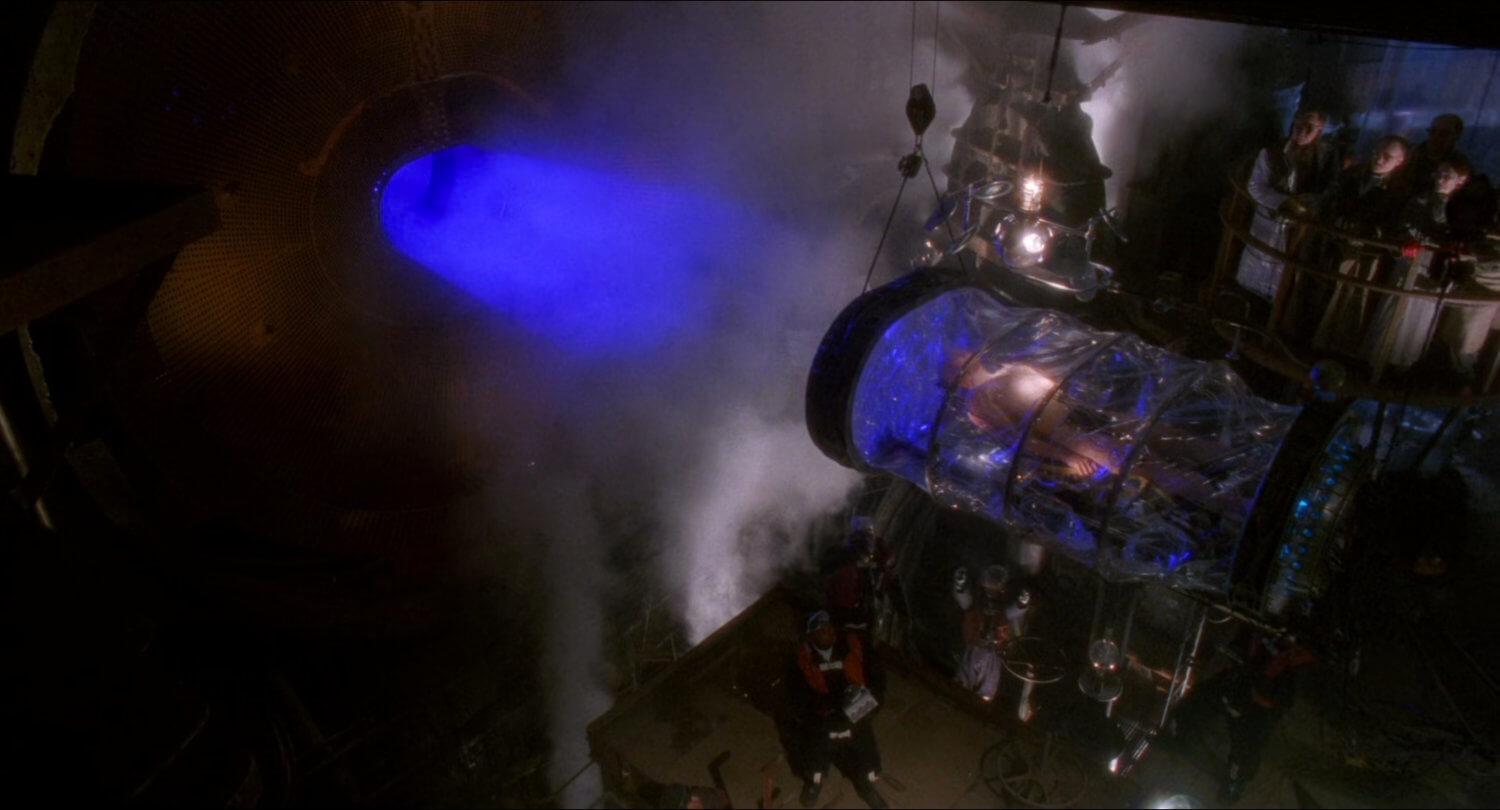

James, seemingly vanishing from 1990, wakes up in solitary confinement 45 years later, where he again finds himself before a committee assessing his actions as part of the assigned task. It then turns out that instead of in 1996, when the epidemic broke out, he landed six years earlier, which made him unable to complete the task. The commission decides to send him back in time once again. At this point, for the only time in the entire session, Gilliam shows the process of preparing and dispatching the Time Probe. This process, cleared of the futuristic envelope, looks nothing more or less than… a computer tomography procedure (the colors draw special attention).

|  |

Year 1996

Cole runs into Dr. Reilly again six years after the events in the psychiatric hospital – he ambushes her near the university when she returns from a lecture on Kassandra Syndrome (prophecy of the doom of humanity) and the promotion of her new book. Convinced that the Army of the 12 Monkeys, led by Jeffrey Goins, is responsible for spreading the deadly virus, he attends a party organized by Jeffrey’s Nobel Prize-winning virologist father, where he is kicked out by the guards after an altercation with young Goins. During the escape, Cole disappears again.

Year 2035

This is James’ last return to the reality of 2035 and the last meeting with the commission, which, initially unconvinced as to Cole’s mental stability, decides to send him on the final stage of the mission to save humanity from extinction.

Competing realities

Already at this stage, the conclusions from the analysis of the traces left to the viewer by Gilliam seem clear. Too many coincidences here.

There can be only one conclusion: there is no time travel!

The events of 2035 are entirely a figment of the imagination of the mentally ill James Cole, and 12 Monkeys is not a sci-fi film, but a carefully crafted study of madness. Already the initial scenes bring a hint that the protagonist’s surroundings are not reality, but the delusions of a sick mind. The dream quoted in the first paragraphs is in fact a message to the viewer that the protagonist is moving in a non-existent reality. Also, Cole’s foil coat, the shower scene, the medical board, the confusing resemblance between the time probe and the CT scan, and other events (to name but a few) are Gilliam’s clues that, in James’s mind, facts, objects, and people, which he knows from his surroundings, become elements used to arrange his alternative reality; reality of a sick mind.

In fact, there are many more such projections in the film. And these are not the only facts that speak for it. Kathryn Reilly hints to Cole (and not only him) several times that she has met him before. This happens already in their first scene together in the detention center (later at the meeting of the medical board and in the cinema during the escape). Maybe he was just her patient in the past, or maybe she herself is a figment of his imagination? Of course, it is possible to find a certain logic and consistency in Cole’s reality, but it is a twisted logic, mixing the order, time and order, according to the current needs of the brain infected with the disease.

The thesis that the year 1996 is de facto the present in the film, and nothing else exists, also seems to be supported by the very different stylistic devices used by Gilliam to distinguish what is real from what is made up. The scenes taking place in 1990 and later in 1996 are filmed very “classically”, very Hollywood – both in terms of the plot and the means of expression used. The year 2035, on the other hand, is pure surrealism – Gilliam’s characteristic style known from Brazil, Time Bandits or The Adventures of Baron Munchausen; not to mention Monty Python.

Each element of this reality functions as if it were viewed through distorting glasses, as if it were its own caricature or a dream with its own rules.

It is also worth noting that, unlike the reality of 1990/96, the reality of 2035 only exists when James Cole is in it. There is not a single scene in the film that would show this time “in the absence” of the main character, and the characters he meets there have never been shown as having their own, independent existence. This is because they exist only in the subjective reality of Cole’s psyche – they disappear when he changes “dimension”.

The situation is different when we move to the reality of 1990/96 – there the characters have their own lives independent of the presence of the main character, and this is because they exist “objectively”, they are not dependent on him in any way. The year 2035 also has one more characteristic feature: everything that appears in it (except the time machine, of course) is made of materials known to Cole from the 90s – there are no futuristic shapes, tools, products of progressive technology, vehicles of the future , etc. This is a projection of the character’s current knowledge onto reality 40 years later. Gilliam and 12 Monkeys writers David Peoples (Blade Runner) and Janet Peoples also endowed Cole with a set of behaviors that would hardly be considered normal: eating a spider, recurring haunting musical themes (Florida Keys, Blueberry Hill), repeated voices from nowhere (however, having their real prototype, which is then reproduced by the character’s mind), unusual behavior (dancing in the water, burst of enthusiasm in Kathryn’s car), an attempt to talk to the radio. In a word: James Cole is a textbook madman.

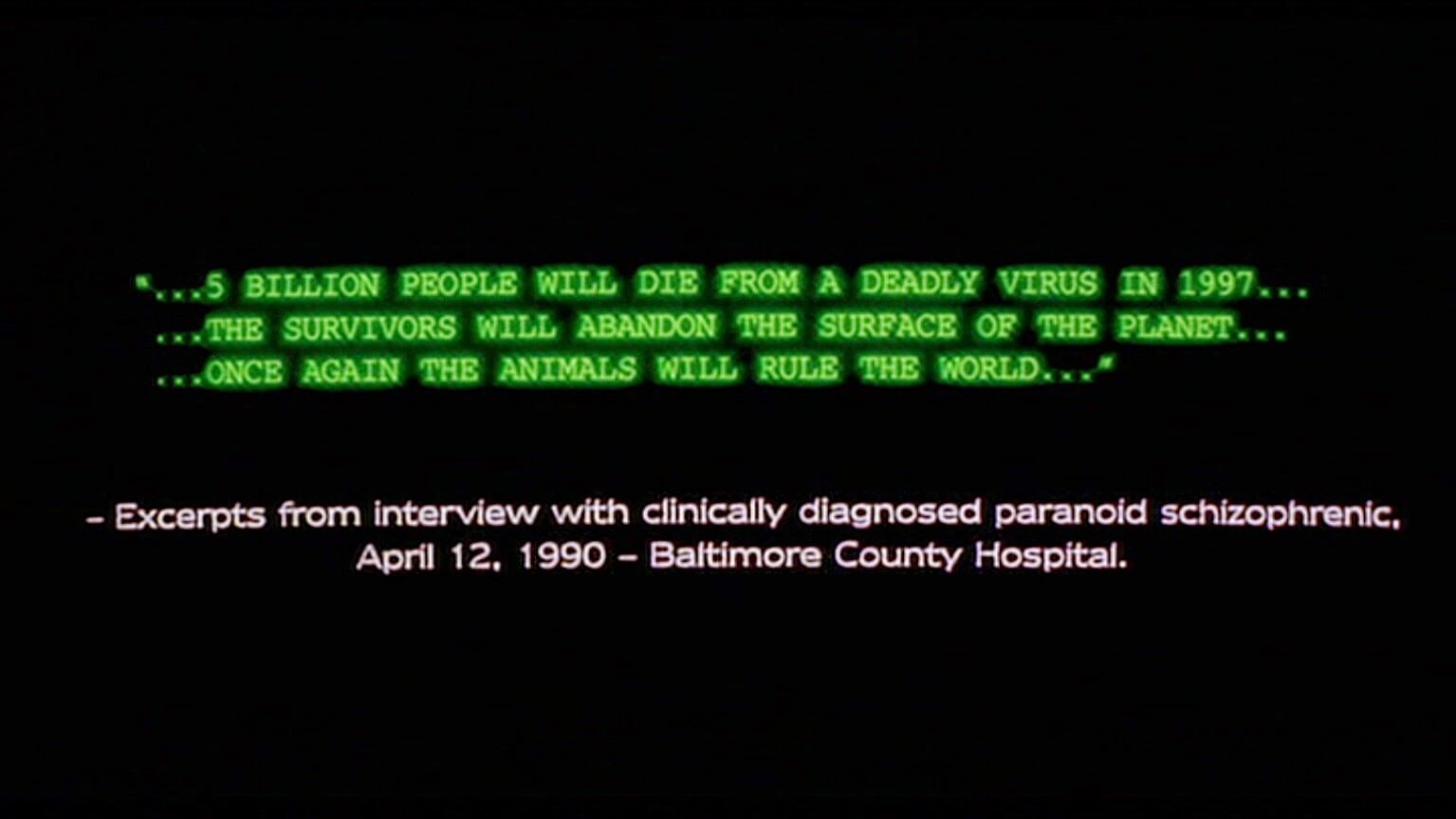

Terry Gilliam and the screenwriters, however, do not leave the viewer completely without help in deciphering the true meaning of the film’s content – he spreads clues during the screening that what you see on the screen is not necessarily what it seems at first glance. Unfortunately, it is not enough to watch the film once to immediately notice them. Gilliam begins the movie with a quote (before the opening credits) that first indicates that what the viewer will see after it is not necessarily to be taken literally.

Another very clear trace indicating the path that the viewer should follow was put by the creators in the mouth of an inmate of an insane asylum, directing his unusual speech to our hero, probably not by chance.

It’s a condition of mental divergence. I find myself on the planet Ogo. Part of an intellectual elite… preparing to subjugate the barbarian hordes on Pluto. But even though this is a totally convincing reality for me in every way, nevertheless, Ogo is actually a construct of my psyche. I am mentally divergent in that I am escaping certain unnamed realities that plague my life here. When I stop going there, I will be well. Are you also divergent friend?

Gilliam’s typical perversity is to put the clue to the film’s subtext in the mouth of a madman. Because how, if not as a suggestion that the protagonist creates an alternative reality in his head, should his words be interpreted?

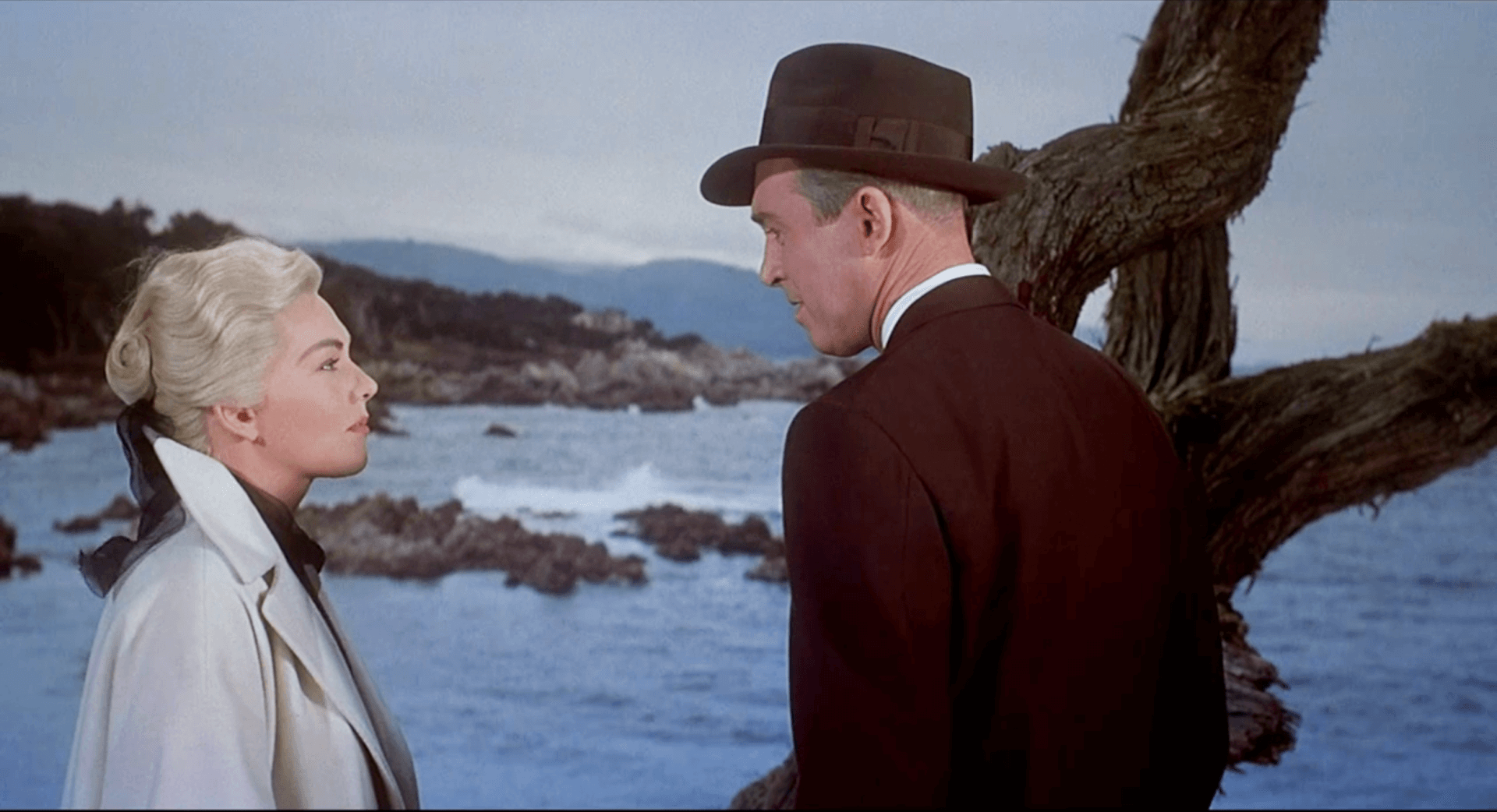

However, perhaps the most explicit and in itself worthy of a separate analysis is the thread that is worth calling “The Vertigo Thread”, because it is a tribute to Hitchcock and one of his greatest achievements, i.e. Vertigo. While on the run from the police, Kathryn and James end up at a movie theater where Hitch’s retrospective is on. Gilliam shows a scene from “Vertigo” in which James Stewart and Kim Novak talk in a redwood forest, and the writers have Cole say words during the screening, the meaning of which hardly needs any additional comment.

The movie never changes. It can’t change. But every time you see it, it seems different because you’re different. You see different things.

We are simply encouraged to watch the film several times, because it may hide something more than meets the eye.

Dream once again

James Cole’s dream is a motif that repeats several times in the film and binds its entire story together. In each installment of it, we see new facts, only to finally find out that it is more than just a dream. The interpretation, which seems to impose itself, clearly indicates that young Cole is watching the death of himself, only 40 years older. Of course, such an interpretation leads to the conclusion that time travel did take place. And so it would be if the whole action at the airport really happened. First things first.

As we remember, the dream sequence opens the film. Then it doesn’t reveal much: we don’t know who the man is falling on the terminal floor, we don’t know who the woman kneeling next to him is, we don’t see their faces.

|  |

The dream sequence will return four more times in the film, revealing more and more details each time. The second time we see her is when Cole ends up in a mental hospital. This time, Dr. Reilly and the fleeing individual in a yellow jacket with a suitcase appear in the dream.

|  |

The third dream sequence follows Cole’s disappearance from solitary before he wakes up in 2035. The dream shows a man shooting, and the guy with the suitcase turns out to be Jeffrey Goins (in red hair).

|  |

The dream returns a fourth time as James is sent back to 1996 proper this time; while on the run from Dr. Reilly. Now we see a man with a gun falling down and very clearly Kathryn (dyed blonde) running towards him.

|  |

When we see the dream for the fifth time (at the cinema, during a review of Hitchcock films), it is only a brief clip of Kathryn running.

It’s an interpretation of reality processed by Cole’s mind.

What’s more, the dream in an altered form appears in the film once again – this is, of course, the entire final sequence in the airport terminal. Someone could tap their forehead here saying that the dream we watched throughout the movie is a memory of young Cole, a memory that is triggered by the events at the airport. So what makes me think this is also a dream? The moment when the whole “airport” sequence begins is marked by Gilliam with one shot, which is not easy to see and read when watching the film for the first time. As Dr. Reilly and Cole enter the terminal door, James pauses for a moment, removes his glasses and states that he knows the place. At this point, Gilliam shows the terminal. People in the terminal have their faces covered with a kind of theatrical lipstick – a mask. This suggests that this sequence is not really happening, that it is in fact another creation of James’s mind.

What connects them all? Of course, they all show details of the same scene, but it’s worth looking at them in some context. Let this context be the timeline of our hero. When we meet him, the dream only shows a man from behind and a blonde woman whose face is obscured by her hair – we don’t know who they are. After Cole meets Dr. Reilly, the unnamed blonde gains face, and after he meets Goins, the man with the suitcase suddenly turns out to be him. It’s dream logic. James did not dream about Goins and Dr. Reilly from the beginning, he only puts them into his dream after he meets them. Thus, the “content” of a dream changes over time, and the sequence we see at the beginning is not the same one at the end.

Finale

This would also be indicated by a certain mixing of Cole’s worlds, which manifests itself in the simultaneous appearance of several characters from the reality of 2035 (the guard and Jose – fellow prisoner). I would venture to say that the airport here becomes a kind of borderline experience for Cole – a place where the created – surreal reality meets the actual reality. The effect of such a contact can not end well…

The film’s original ending was when Kathryn, kneeling over Cole in the airport lobby, met the gaze of young James. Such an ending would have the greatest power and create a certain, in its own way logical, though at times very surreal whole. What’s more, it would close the whole film in a bracket, summing up the unreality of the main character’s impressions and feelings. And, what can I say, it would be very “Gilliamish”. Unfortunately, at the request of the producers, the director added two more scenes that significantly dilute the message of the film and add something like a happy ending, unfortunately quite trivial with all this lacy story.

The scene in the plane, in which we see a woman – a member of the commission from the future and the main culprit of future destruction, suggests that Cole’s death was not in vain, and people from the future managed to finally reach the original form of the virus. In the second scene, we see young Cole with his parents in a large airport parking lot. If I were to try to interpret it, I would bet on the good old life goes on. In any case, both sequences are completely incompatible with the well-thought-out whole and I have the impression that they were intended, as suggested by the producers, to improve the mood of potential viewers after a rather depressing journey into the psyche of a madman. It reminds a bit of many years later (and unfortunately largely lost) fights with producers fought by Gilliam for the final shape of The Brothers Grimm. But that’s a completely different story…

P.S.

12 Monkeys is one of the most outstanding films of the 1990s. It is certainly not just a serial science fiction production and it is worth giving it another chance, reaching to the shelf with the slightly dusty DVD edition to explore the perhaps previously unknown details. The picture, despite the years that have passed since its premiere, is surprisingly strong in every respect and will not disappoint anyone who wants to open up to the slightly crazy, but always captivating world of the great cinema magician, Terry Gilliam.

Read 12 Monkeys explained continued.