HEAVEN’S GATE: The Story Behind a Disastrous Masterpiece

At this moment, like few before him and even fewer after, Cimino could afford to do literally anything. He pulls out a script written at the beginning of the decade for his dream project, depicting a bloody chapter of American history, and convinces United Artists to fund it entirely without supervision. The producers agree without hesitation, sensing another major hit of the season. Convinced of his infallibility, Cimino steps onto the set of… Heaven’s Gate.

1870. The prestigious Harvard University is bidding farewell to another generation of its students. Among them are James Averill (Kris Kristofferson in the role of his life) and Billy Irvine (the much-missed John Hurt)—two best friends who seem to be well-liked stars in vastly different areas of life. Averill is the athletic type—a typical American “golden boy.” Irvine, on the other hand, has the gift of gab—a thinker who poses as the class clown. While James enjoys the farewell party, feeling that the world belongs to him, Billy alone drowns his sorrows over the future, bidding farewell to a paradise lost.

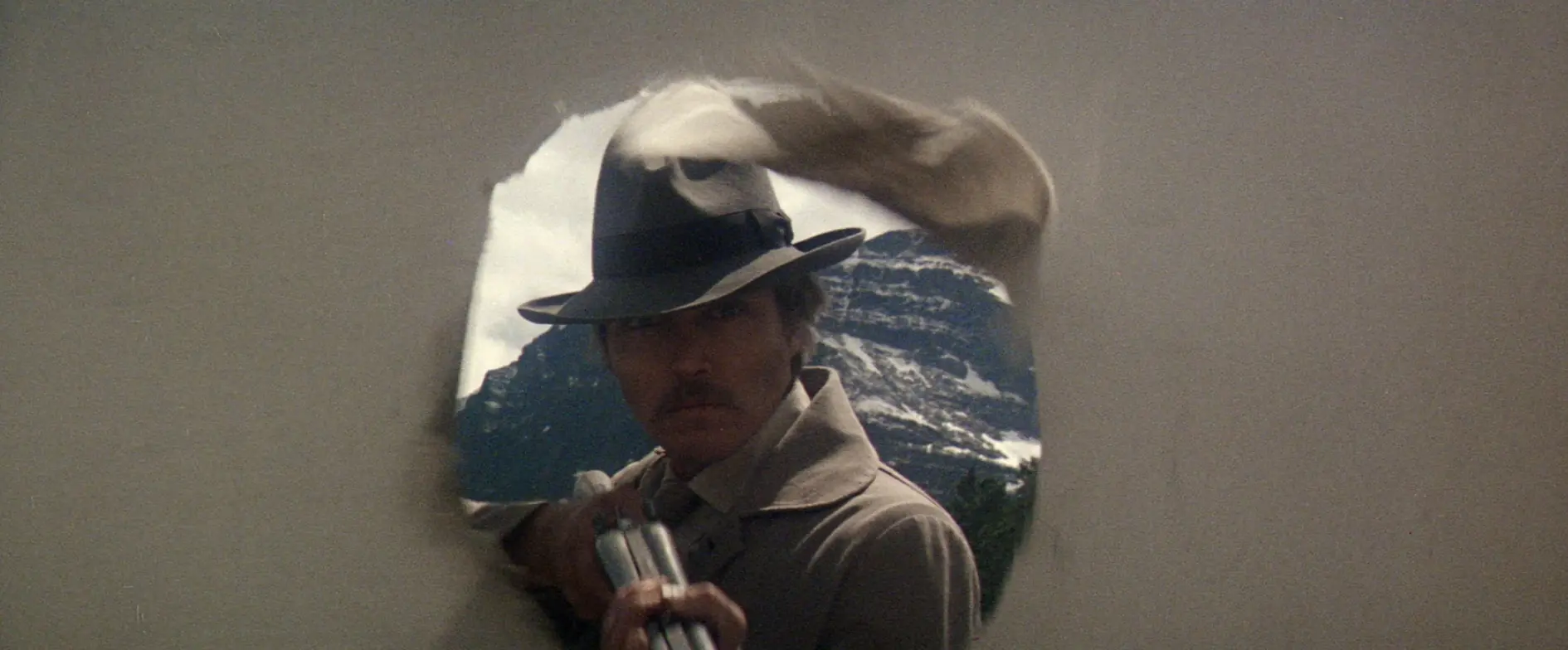

Twenty years later, they meet on opposite sides of the barricade. Averill is now a sheriff in Johnson County (Wyoming, here portrayed by the equally stunning landscapes of Montana and Idaho). He mingles with the working class, is in love with a prostitute (Isabelle Huppert in her first English-speaking role), and defends the interests of the growing number of European immigrants. Meanwhile, Irvine remains among the elite—frequenting the lavish salons of the Cattlemen’s Association, whose members dream of quickly ridding the land of outsiders. To achieve this, they hire another of Averill’s friends, Nathan Champion (the inimitable Christopher Walken)—a ruthless man quick to pull the trigger, though he also has his own interests among the people he is tasked with eliminating. A bloody confrontation is inevitable…

Those even somewhat familiar with U.S. history from the era of the real Wild West (here already yielding to progress) will likely guess that this involves the Johnson County War (1889–1893), which was indirectly featured in earlier classics like Shane and The Virginian. Indeed, the original title of Cimino’s screenplay was The Johnson County War. However, the director ultimately settled on Heaven’s Gate (after a skating rink featured in several scenes—a little piece of heaven), using the war merely as a backdrop for a love story. He selectively uses historical facts to highlight the eternal conflict between the rich and the poor, where those in power dictate harsh conditions, and the rest must adapt or perish. It’s no surprise, then, that his film—a Western and anti-Western in one—is steeped in bitterness to the very end, only seemingly happy on the surface. Nor is it surprising that the production was a complete commercial failure.

The premiere, which took place 45 years ago, was delayed by a full year, primarily due to Cimino’s perfectionism. Nicknamed “The Ayatollah” by his crew, his approach rivaled the obsessive methods of Stanley Kubrick or the then-fresh reports from the set of Apocalypse Now. In fact, the press mockingly referred to the project as Apocalypse Next. Legends surrounded what Cimino did during filming: regularly insulting actors and crew, firing and rehiring staff weekly (a fate suffered by a young Willem Dafoe, whose debut role as Willy was cut entirely), and demolishing meticulously constructed sets were reportedly standard practices.

Cruel treatment of animals—primarily roosters and horses—was another issue, with at least four animals dying during filming. This controversy led to the implementation of animal welfare oversight in the industry, marked by the now-familiar disclaimer, “No animals were harmed in the making of this film.” Cimino’s obsession with perfection extended to the opening scenes at Harvard (actually shot at Oxford and Cambridge), where a massive tree was cut down, chopped into pieces, and transported from another location entirely. Filming took place exclusively on real locations, and like Days of Heaven, many scenes were shot during the so-called magic hour (the brief moment between sunset and nightfall), which only deepened the chaos of the production.

Unstable weather, lengthy commutes to remote locations involving over 2,500 extras, 150 craftsmen, and 80 horse teams; constant on-the-fly script rewrites; and numerous disputes between Cimino and the producers (for instance, over casting Isabelle Huppert, whom UA executives considered too… unattractive). These and other issues meant that after just five days of filming, the production was already four days behind schedule—exactly the length of Sam Peckinpah’s visit to the set (coincidence?).

Much of the crew often spent hours, sometimes days, waiting for their turn. This waiting occasionally stretched to absurd lengths, prompting those involved to seek other challenges. For instance, John Williams, the composer initially attached to the project, withdrew after Cimino fell six months behind schedule. He was replaced by a young David Mansfield, who not only composed the score but also appeared on screen as the cheerful fiddler John DeCory. Meanwhile, John Hurt completed all his scenes for The Elephant Man and then calmly returned to Heaven’s Gate, which was still filming in Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

All these factors naturally impacted the budget, which quickly grew from a “modest” eleven million dollars to four times that amount, resulting in a total expenditure equivalent to today’s 200 million dollars (!!!), making it one of the most expensive investments of its time (though, paradoxically, not for United Artists, whose peak expense during this period was the latest James Bond adventure, Moonraker). This illustrates not only Cimino’s inflated ego—who, by the way, managed to squeeze extra money out of the producers by placing parts of the production on land he owned—but also the immense complexity of the undertaking and the sheer scale of the spectacle. The magnitude is further evidenced by the amount of footage ultimately recorded.

Over nearly six months of filming, nearly half a million meters of 70mm film were used. From this, the director personally, under lock and key and with an editing room protected from producer interference, pieced together a five-and-a-half-hour foundational version of the fresco. This was later trimmed, also by Cimino himself, to 219 minutes (for comparison: The Deer Hunter was 183 minutes long). The studio then further edited the film down to a more audience-friendly two and a half hours. However, such measures did not prevent the movie from becoming a financial disaster, a failure not solely caused by its widely criticized R rating.

To say that Heaven’s Gate flopped at the box office is to say almost nothing. With total earnings of just five million dollars (including subsequent home distribution), it was a true disaster—one of the greatest in the history of cinema. As a result, United Artists was pushed to the brink of bankruptcy and was ultimately acquired by MGM. The failure was so loud and so devastating that for years Heaven’s Gate became synonymous with cinematic disaster in the industry. When similar issues plagued Kevin Costner’s Waterworld in 1995, the press sarcastically referred to it as “Kevin’s Gate.”

Moreover, Cimino’s failure definitively marked the end of the high-budget auteur-driven spectacles of the 1970s, restoring the studio control that remains dominant today. This was the culmination of several other financial misfires from that era, including William Friedkin’s Sorcerer and The Brink’s Job, Steven Spielberg’s war comedy 1941, Warren Beatty’s Reds, and finally Francis Ford Coppola’s One from the Heart. All of these filmmakers were once seen as revelations, delivering masterpieces that were also box office hits. However, each severely strained their reputations with bold, costly projects. Except for Spielberg, none of them managed to bounce back. Yet none fell with as loud a crash as Cimino.

The director was not only forced to bury his next project—a western based on Frederick Manfred’s novel Conquering Horse, telling the story of the Sioux (Dakota people) and planned to be shot entirely in their language (a concept later realized by Mel Gibson in Apocalypto)—but also found himself unable to secure any work for the next five years. From Hollywood’s golden child, he became its most unwanted outcast. Furthermore, every subsequent film Cimino made after Heaven’s Gate also left much to be desired financially. One could even argue that Cimino disappeared overnight into the abyss of the American dream factory.

Cimino also dragged Kris Kristofferson down with him. His position as a leading star was similarly buried, and from that point onward, Kristofferson—who described the role as the hardest and simultaneously the most satisfying work of his career, something he would remain proud of for the rest of his life—was relegated mainly to supporting roles or memorable cameos. Interestingly, all these consequences seemed to bypass the Western genre itself. At the time in crisis, caught between its classical and revisionist forms, the genre only saw a revival in subsequent years, ultimately returning in a blaze of glory thanks to… Costner and his Dances with Wolves.

For the producers of Heaven’s Gate, a consolation prize came in the form of an Oscar nomination for Art Direction—especially when compared to the Golden Raspberry Award bestowed upon the film for Worst Director and several other nominations for this dubious honor. A few positive voices in favor of the production couldn’t mask the overall negative reception, not only among audiences but also critics. American critics were particularly harsh on the film (often even before watching it!), only appreciating it more as time passed. Reception in other countries wasn’t much better, though the further east one traveled from Eden (New York’s Eden, of course), the more favorable the views became.

Especially in France, this work—like nearly all of Cimino’s other films—was loved from the beginning, earning him a Palme d’Or nomination and, years later, the chance to revisit his creation. This resulted in the release of the 2012 director’s cut, with a runtime of 217 minutes—closest to his vision, and given the director’s passing, considered the definitive and sole authoritative version. It was also appropriately restored, refreshed (including color grading), and corrected for technical errors to meet modern standards. And… how beautiful it is.

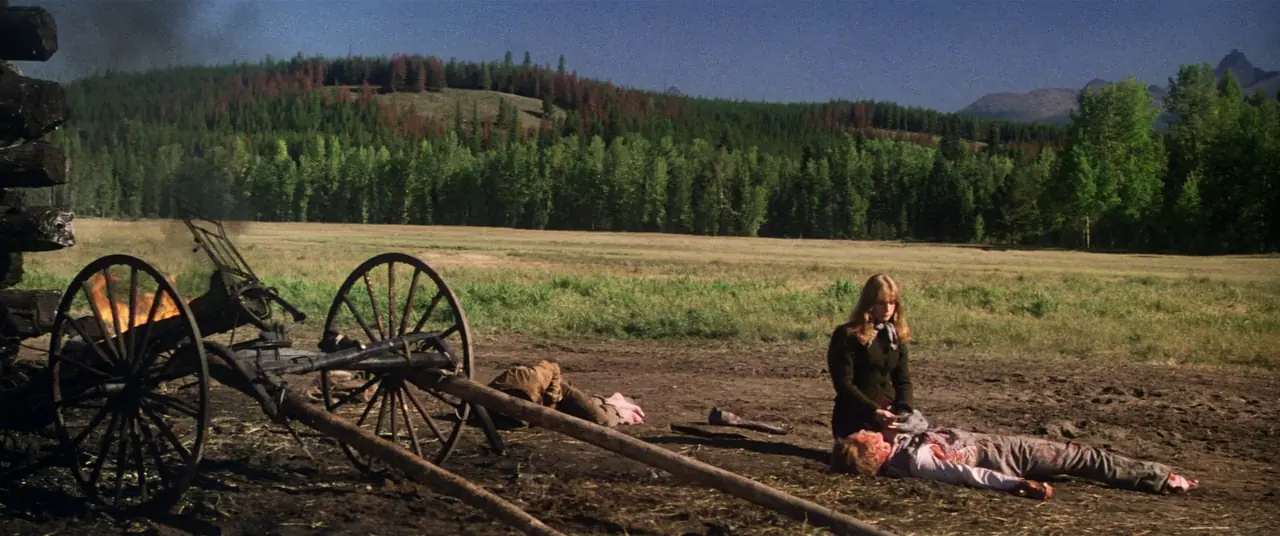

Abstracting from all the production dilemmas, historical intricacies, and the exceptionally poor reception upon its release, this is a truly breathtaking piece of cinema—rich, colorful, and crafted with extraordinary meticulousness. And it’s not just about the painterly frames of the legendary Vilmos Zsigmond’s camera, the stunning landscapes of wild prairies, and the majestic mountains stretching to the horizon. Nor is it solely about the bucolic and homely charm imbued in the moving picture, tinged with a note of bitterness but also genuine optimism, accompanied by a delightful soundtrack. This music includes The Blue Danube by Johann Strauss and lively performances by a “rural” band featuring the aforementioned Mansfield and T Bone Burnett.

Although the intrigue is relatively simple and the plot is smoothly executed in a classic, experiment-free style—both in form and substance—its universality can captivate, while its calm style—devoid of excessive pathos, fiery speeches glorifying the nation, and waving stars-and-stripes flags—is enthralling. The romantic nature of the story, its setting in a context that is historically relevant to us as well, and the neutrality, even innocence, of the untouched nature surrounding the settlers, creates an unforgettable atmosphere. It adds flavor to the adventure, intensifies emotions—sometimes even generating them in the numerous characters who are driven by it to act. After all, the battle here is about a magnificent land, unspoiled by the sins of civilization.

In this battle, alongside the previously mentioned Hurt, Kristofferson, Huppert, and Walken, the cast includes an ensemble of remarkable actors—perfectly chosen to enhance engagement with the cause (currently relevant, albeit for different reasons). Sam Waterston is superb with his mustache as the villainous Frank Canton, and Joseph Cotten wrings everything out of his modest yet crucial cameo. Jeff Bridges shines, as usual, playing… his own ancestor, John L. Bridges, which he himself suggested to the director. Like Kristofferson, he was also extremely proud of this film. He was the only one from the crew to keep a modest piece of it—a part of the set, a small house, which now stands on his property in Montana.

Ronnie Hawkins, Paul Koslo, Geoffrey Lewis, Richard Masur, Tom Noonan, and Mickey Rourke complete this stellar cast, turning even the smallest roles into fully realized characters—memorable not just because of the familiar faces behind them. This film also marked the debut of notable figures: the distinctive Kai Wulff, one of Hollywood’s go-to Germans (Three Amigos), and Terry O’Quinn, best known today for the series Lost, whose life was literally set on track by this job as he met… his future wife on set. Finally, Brad Dourif is fantastic as the timid, slightly awkward Eggleston, associated with another significant and successful aspect of the film that deserves special mention.

In the multicultural immigrant community depicted in the film, there was also room for Poles (representing the remnants of a homeland that did not exist at that time). Hence, the cast includes Waldemar Kalinowski, Margaret Benczak, and a few other Polish-sounding names. This is hardly surprising, given our significant contribution to building the myth of the United States, and the fact that Poles often appear in Cimino’s films, even in the background. Cimino himself always spoke appreciatively of the Polish people. However, the Polish language has never garnered as much attention in his work as it does here. This is largely due to the well-crafted portrayal of “minor” characters of Slavic origin and the beautifully delivered lines in Polish—most notably by Dourif, who handles the challenge masterfully. In this regard, the film is a true gem in cultivating the Polish image on the big screen, and it serves as the cherry on top of the overall brilliance of Heaven’s Gate.

Of course, the production is not without its flaws. For one, the typical Hollywood approach of loosely interpreting—or even distorting—historical facts (e.g., the real James Averill was hanged alongside Ella in front of their home, and the U.S. Army seen in action here was not part of the bloody conflict but rather its resolution). Additionally, the pervasive presence of smoke or dust in many frames can make the viewing experience challenging, as does the film’s considerable length. The runtime, in particular, can sometimes become a bit taxing and may deter less patient cinephiles.

While there are hardly any scenes that are entirely superfluous or fail to contribute to the plot, and some storylines even feel like they could have been explored further, it’s difficult to shake the impression that the film could have been slightly shorter overall. Despite featuring truly spectacular scenes (as well as sex, blood, and profanity), the director clearly prioritizes exposition over action, focusing on credibility and complex relationships rather than fireworks. He luxuriates in individual shots, breaking the drama and narrative flow of the spectacle, unconcerned with time. But that’s also the nature of this film—poetic, one to be savored in much the same way.

Heaven’s Gate is a film that can be written about, reflected upon, and debated endlessly—a hallmark of the greatest works of cinema. Indeed, since its premiere, countless publications have been devoted to Michael Cimino’s film—essays, articles, books, and even documentaries analyzing the genesis, production, and colossal failure of the entire venture. Yet, perhaps the best summary of the project (and its creator) comes from the film’s editor, William Reynolds:

“Michael didn’t want respect. He wanted admiration.”

The bastard succeeded—though he paid an enormous price for it.