PERFECT BLUE. Astonishing anime masterpiece

At the beginning, there was Yoshikazu Takeuchi’s novel Perfect Blue. Then there was supposed to be a live-action film adaptation. Takeuchi even wrote a screenplay, which caught the attention of producer Koichi Okamoto. However, the Rex Entertainment studio, to which the project was presented, postponed its realization “for later” because of the devastating earthquake that struck Kobe in 1995. Ultimately, it was decided that it would be easier to create an animated version of Takeuchi’s novel. The project then moved to the Madhouse studio, where it ended up in the hands of Katsuhiro Otomo, the creator of the famous Akira. Otomo recommended his recent collaborator, Satoshi Kon, with whom he had worked on the short film titled Magnetic Rose as part of the Memories project.

The color of illusion is Perfect Blue

Satoshi Kon had been fascinated by manga since childhood. He immersed himself in popular comics like Yamato and Gundam, but he held a special appreciation for the works of Katsuhiro Otomo, who would later become famous in the anime creator community. Young Kon was also interested in live-action films, especially those by Akira Kurosawa and, significantly for his own creative work, Terry Gilliam. Besides cinema, he was drawn to art and drawing.

Like many anime creators, Kon started his career by creating manga, one of which even received an award from Kodansha. Starting in 1991, he worked in the anime industry, initially in the field of art design and later collaborating on various projects. While working on Memories, as mentioned earlier, he had the opportunity to meet his longtime idol, Otomo. Eventually, it was time for his fully independent directorial debut – Perfect Blue.

Kon didn’t read Takeuchi’s novel, and the screenplay didn’t particularly interest him. However, he agreed to direct the film on the condition that he could make significant changes to the script. Takeuchi and Okamoto didn’t oppose this, mainly due to their frustration with the constant delays in realizing their project. They only requested that the newcomer preserve the core of the script, which was the storyline of an idol being persecuted by a fanatical admirer. Kon requested a rewrite of the script from Sadayuki Murai, who had previously been involved in organizing events featuring idols before becoming a screenwriter. Changes were made, including the introduction of the “film within a film” subplot and the theme of the gradual blurring of reality. Kon also came up with the idea of an online diary supposedly maintained by the film’s protagonist, Mima. Interestingly, the director didn’t purchase a computer until after completing the film – he didn’t have one before. What’s more important is that all these changes turned out to be spot on.

Stalker movie?

At first glance, the plot of Perfect Blue adheres to the formula of so-called stalker movies, which are films about persecutors. This subgenre of thrillers, in which the persecutor is an obsessively infatuated fan of their idol, typically features several recurring elements. Firstly, the fan’s obsession often consumes their entire life, and they try to mask their own frustrations or failures in relationships with other people through their adoration of the idol. The idol becomes an ideal and a paragon of perfection for the fan. Secondly, the theme of these films revolves around the idol’s “betrayal” – the idol may change their image, end their career, switch to a different team (The Fan), kill off the fan’s favorite fictional character (Misery), or in some other way deviate from the idealized image that the fan has of them. The consequence of this betrayal is increasingly intrusive attempts by the fan to influence the idol, hoping that they will recognize their mistake and return to the discarded image. The climax usually involves a showdown between the fan, who is in a state of complete paranoia, and the idol, who is fighting for their life or the lives of their loved ones.

All these elements of stalker movies can be found in Perfect Blue. The difference lies in the specific social context of Japan. In the Land of the Rising Sun, idols are mass-produced. This is especially true for the creation of various boys or girls bands. The material for these groups consists of young people with attractive looks and not necessarily exceptional musical talent. Catchy names are devised for them, simple melodic hits are composed, and they are put into the marketing machine’s gears. With a bit of patience, another hit is born. If the material is rich enough, you can launch two or three more hits with the same boys or girls band before looking for the next commodity that can be sold well. The word “commodity” is not coincidental because the entertainment industry treats people and their talents as commodities. The only thing that matters is whether they can be sold well. These are the brutal rules of show business. Only a few manage to resist them, and often at a very high cost.

The path to fame

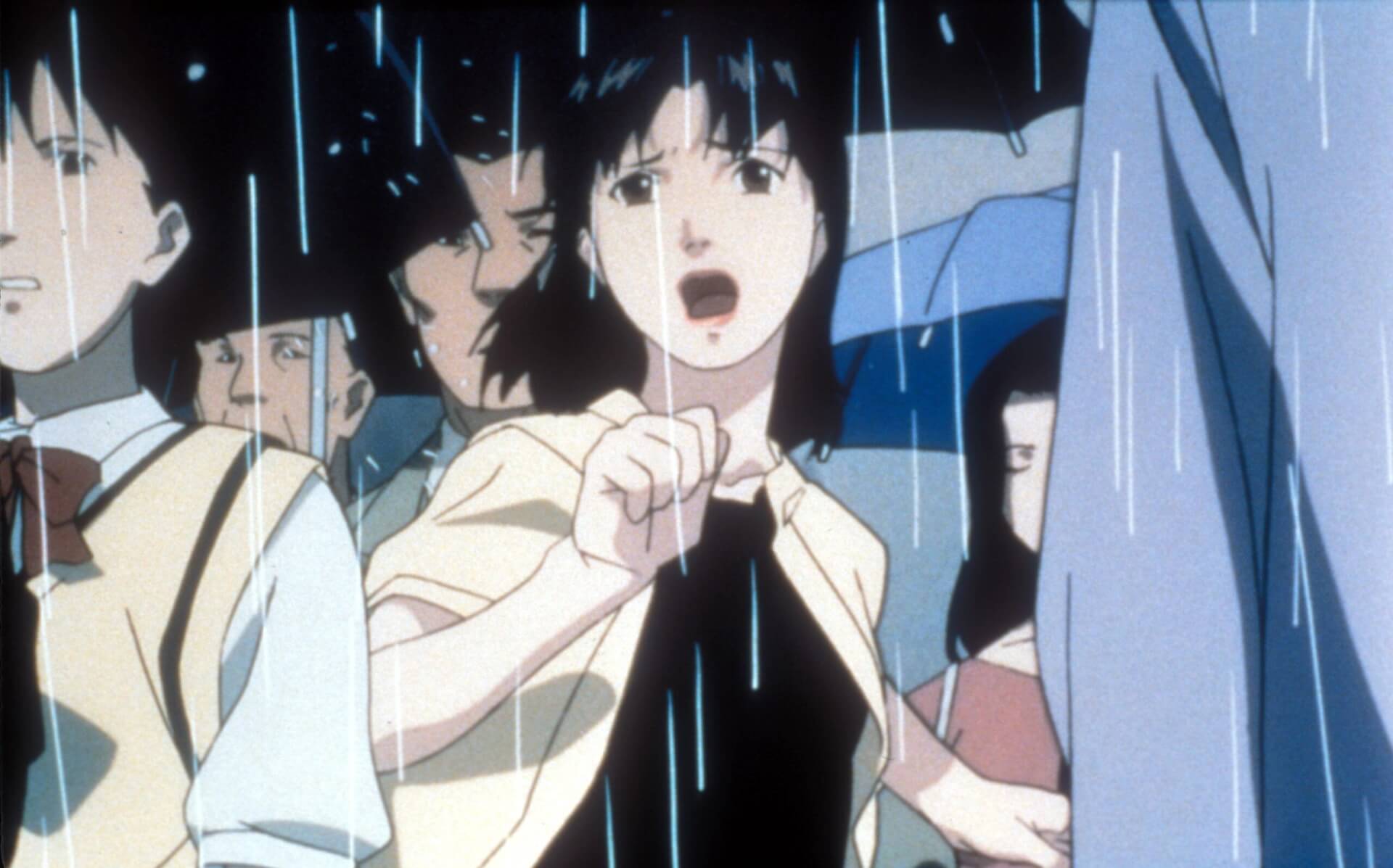

Mima, the pop star of the CHAM trio with a homely-sounding name, is precisely this kind of “commodity.” When she decides to leave the group, it’s not entirely her personal decision. The singer’s manager also encourages her to replace the stage with a photo shoot for the film Double Bind. He sees an opportunity to make money from his ward’s image change. However, this turns out to be not so easy, and quite humiliating for Mima. She starts her acting career with a single line of dialogue, followed by a scene of group rape (the girl motivates herself to play it by repeating to herself: “I’ll do it. After all, I want to act. That famous actress, I can’t remember her name, did the same”). Finally, it’s time for a nude photoshoot and an increasing moral hangover.

It’s true that we’ve seen the ethical dilemmas of a character who agrees to ever greater compromises, gradually losing their basic human decency, before – think of Frank Pierson’s A Star Is Born, James Mangold’s Walk the Line, or even the unsuccessful Showgirls by Paul Verhoeven. However, we’ve probably never seen a portrayal of a character climbing the career ladder at the expense of increasing moral degeneration in an animated film before. And we rarely get such a thorough study of the psychological consequences of the path to fame.

Doppelgänger

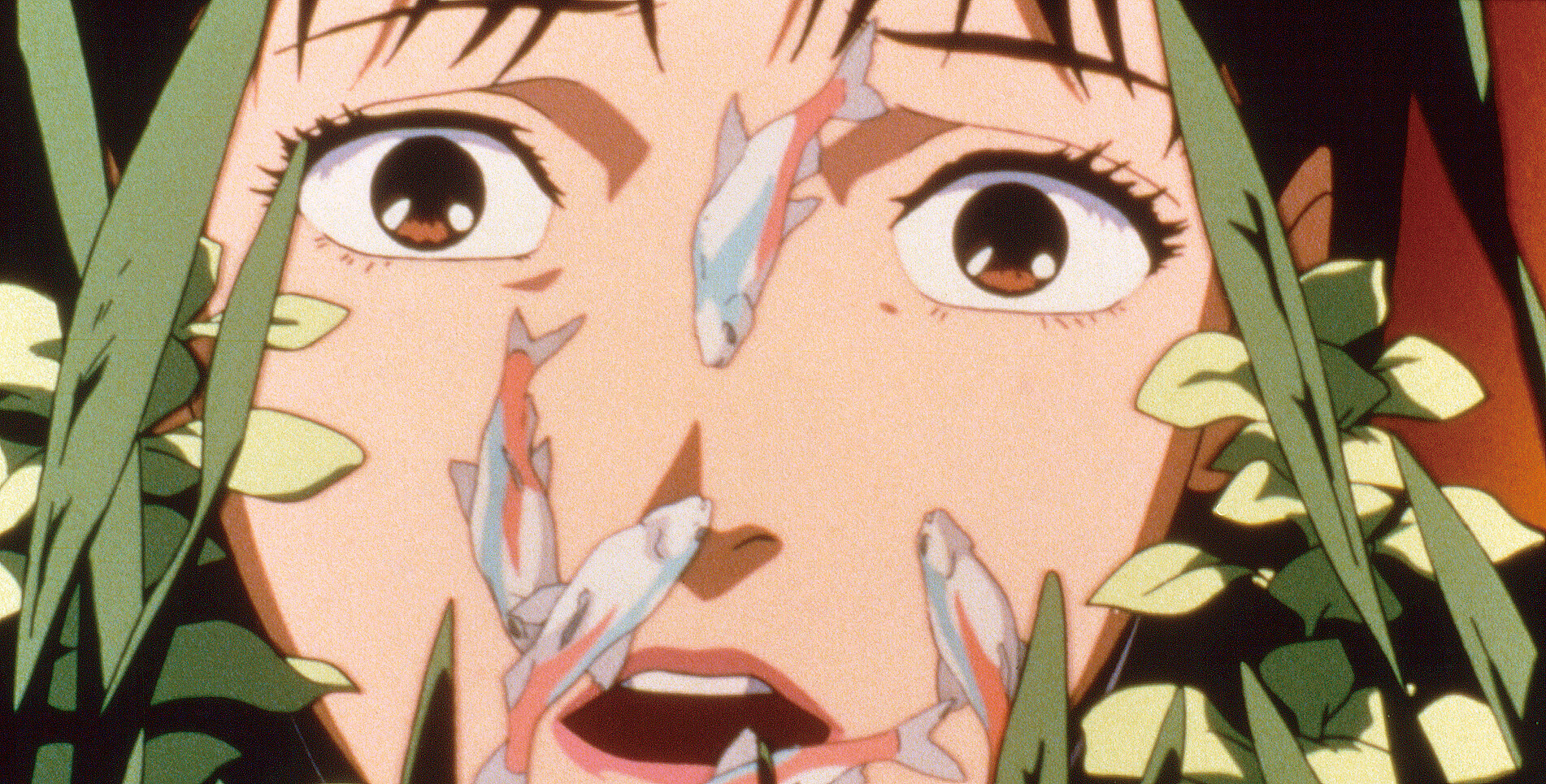

Mima is tormented by guilt not only because of the unexpected success of her former bandmates but also due to many other haunting doubts. Will she be a good actress? Will she get a bigger role? Will the director like her? Is she compromising too much? From these anxieties and her ordinary sense of guilt, Mima’s doppelgänger is born – Mima the singer. The introduction of this doppelgänger serves a hidden purpose. It’s not just emphasizing the inner conflict of the character; it’s one of the elements tearing apart the entire reality of the film.

Mima’s duplicate also serves another role in Perfect Blue, revealing herself to the psychopathic fan known as Me-Mania. To this man, she is the ideal that Mima once was when she sang in the group, and whom he loved so much. Mima the actress is a fraud, an imposter who wants to replace the “real” Mima. Therefore, she must be punished, but first, everyone who contributed to pushing the “real” Mima the singer into the deep shadows must pay the price. The punishment is severe but just. First, the manager is maimed by a letter bomb, then the screenwriter has his eyes gouged out, and finally, in a surprisingly suggestive manner for an animated (but not anime) film, a photographer is gruesomely murdered.

In Perfect Blue, another Mima appears, this time a “cross-dresser.” Much crazier than Me-Mania, who merely served as a tool. Was she the Mima-doppelgänger? We receive a suggestion that she might be, but it remains a suggestion without becoming a certainty.

Otaku

Before we answer why there are so many characters multiplying, it’s worth noting that Perfect Blue not only accurately portrays the image of an “idol for five minutes” but also the specific genre of Japanese fans embodied by Me-Mania. He belongs to the so-called otaku, which can be loosely translated as “fanatic” or “enthusiast.” A typical otaku is a man aged 20-40 who doesn’t care about his external appearance because something else occupies his mind. The everyday life of an otaku consists of obsessively collecting information about favorite products, idols, and/or collecting figurines of beloved (mostly female) characters. What sets them apart from ordinary collectors is that they are deeply addicted to Japanese pop culture products – idols or gadgets. To such an extent that their “passion” replaces normal human relationships. They spend most of their time at home, surfing the internet, as the virtual world is more important to them than the real one. Like Me-Mania, just without the murderous obsession.

Once, otaku were on the fringes of society, but today there are three million of them, and a powerful industry revolves around “otakuism.” They spend 290 trillion yen annually on their passions and pleasures. It’s clear that you can make quite a profit even from social alienation. So, the victim of the heartless show business machinery is not only Mima but perhaps even more so, Me-Mania. He’s not just an otaku – a byproduct of consumerism – but also a mere tool in the hands of the real perpetrator of the crime, and ultimately, a victim of his own imagination. As Joanna Bator writes: An otaku knows only two dimensions: virtual reality and the world of their imagination.

Reality and Buddhism in Perfect Blue

Mentioning the virtual and imagined realities leads us to the central theme of Perfect Blue : a reflection on the nature of human identity and reality. Throughout the entire film, the motif of the real and unreal is ever-present.

Kon multiplies the character of Mima, multiplies reality by introducing hallucinations of the protagonist into the realistic narrative, and frequently employs the “closed loop” device – Mima keeps waking up in her room. Finally, he prominently features mirrors and other reflective surfaces that enhance the impression of the dilution of the nature of the world. All these techniques are consistently utilized in the film. Why? It seems that this is done to depict the ephemerality of the world, its transience, fragility, and impermanence. Of course, in such a world, people are also transient, almost transparent. It’s worth noting that the insignificance of the depicted world is realized on at least two levels. On the social level, it’s expressed in the story about the relative role of today’s idol. On the philosophical (existential) level, it’s expressed through a reference to Buddhism. This religious-philosophical system from the Far East is based on the assumption that phenomena, individuals, and things undergo constant changes, that nothing is permanent. It’s a bit like in a dream, where clear boundaries and a coherent narrative don’t exist. From these assumptions, it’s only a step to recognize emptiness (sunyata) as one of the most important pillars of Buddhism and the most essential characteristic of the nature of the world.

Interestingly, views on impermanence, and even the non-existence of the human “self,” also appear in Western sciences. Scholars like Francisco Varela, Benjamin Libet, and Michael Gazzaniga believe that the coherent consciousness of a person that determines their identity is an illusion. In reality, the sense of being a person is merely a sum of sensory experiences and memories stored in memory. The feeling of unity is the result of evolutionary programming in our brains. Whether this is indeed the case will likely remain a mystery for a long time. And is blue the color of emptiness? Absolutely!

What’s remarkable about Kon’s work is that these kinds of reflections appear in a film that, on the surface, is entertainment. The value of Perfect Blue is further confirmed by the live-action remake, or rather, a faithful adaptation of Takeuchi’s novel by Toshiki Sato in 2002. The film turned out to be a much less intriguing work and remained in the deep shadow of Satoshi Kon’s version.