The best APOCALYPTIC ANIME movies

Animation has long freed itself from being a genre intended solely for children. Especially in Japan, where anime garners applause not only among the youngest audience but also – perhaps primarily – among mature viewers. Japanese animation, however, is not solely represented by the iconic Studio Ghibli. Among the genres in which the Japanese excel and which they translate into their films are science fiction, dystopia, or post-apocalyptic themes, evidenced by renowned anime series such as Ghost in the Shell, Cowboy Bebop, and many others. Often, Japanese fascination with the future, destruction, and devastation approaches the most somber theme – the apocalypse. Although the following list exclusively concerns feature-length animated films, one can still find several exceptionally intriguing examples in this field that illustrate how creators from the Land of the Rising Sun perceive the end of the world. I have selected the titles below in a way that presents various, often entirely distinct, prophecies of doom.

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind

Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is informally considered the first film by the Japanese Studio Ghibli. It tells the story of the titular princess who strives to maintain peace in her realm and balance between humans and nature – a nature that is slowly rejuvenating after a significant ecological catastrophe. Hayao Miyazaki’s film, like his later works, carries ecological and pacifist themes. It presents a world that is regenerating after humanity’s destructive and harmful actions. The film’s setting is in a world significantly projected into the future. Its opening seconds depict a landscape of death and destruction, as if something had poisoned the local environment. These events occur during the so-called “Ceramic Age,” a millennium after the fall of industrial civilization. As it turns out, seemingly innocuous but deadly fungal spores threaten humans. The spore vapors can kill within minutes. Those without protective masks face swift and unexpected death. The most significant threat to the land’s inhabitants is the “Toxic Jungle,” responsible for the world’s ruin in the past. When humanity first fought against it, hordes of giant insects called “ohmu” flooded the Earth. However, the Toxic Jungle continues to expand, poisoning new villages and territories. As the film reveals, this jungle formed due to human activities aimed at absorbing the toxins they produced. Hayao Miyazaki thus presents the audience with a grim vision where human greed has brought about the end of the world. Furthermore, the portrayal of the world a thousand years after the apocalypse is intriguing. It bears resemblances to the medieval era in various aspects, including architecture, clothing, interior decoration, and societal organization – divided into regions ruled by kings and princesses. Nevertheless, the characters still possess modern weaponry like bombers, tanks, and handguns. The flora and fauna are also astonishing – entirely new species of animals exist, but it’s the plant life that plays a crucial role in the film. Nature, the only force that can save humanity from another catastrophe, simultaneously becomes its most significant threat.

Related:

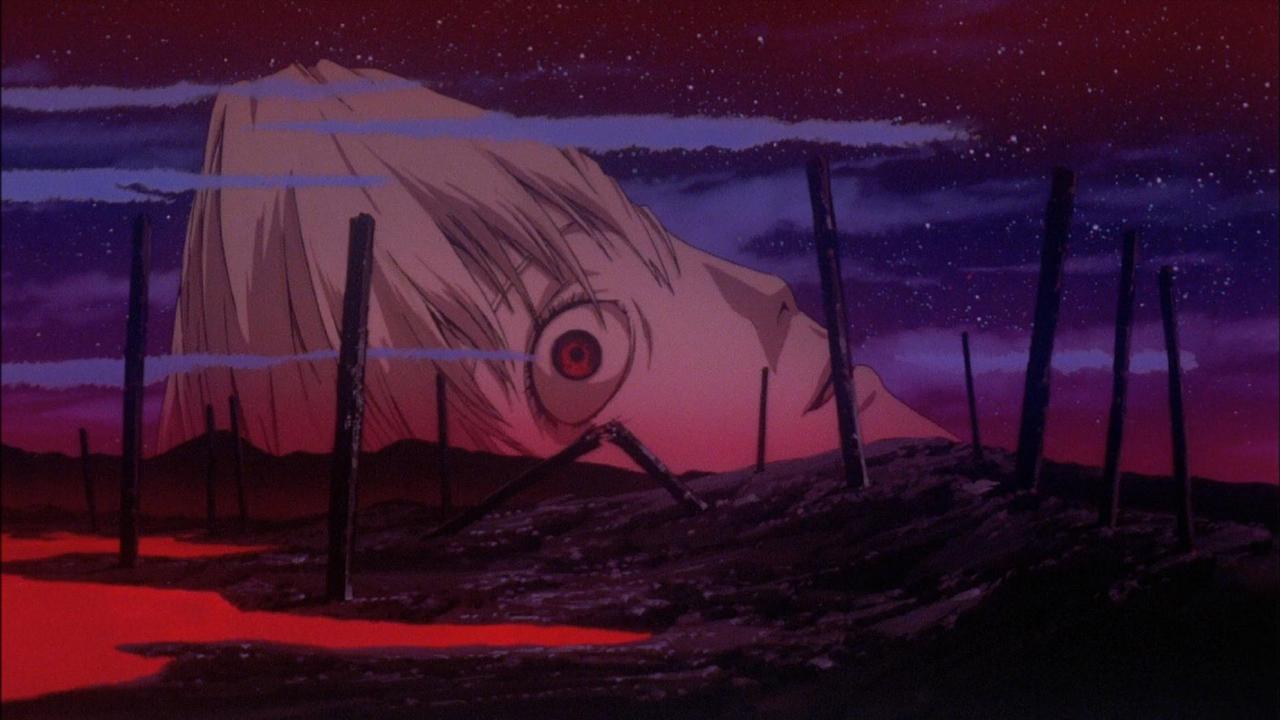

The End of Evangelion

The End of Evangelion is the film that concludes the animated series Neon Genesis Evangelion from 1995-1996. Its story is set in the year 2015, 15 years after a catastrophe known as the Second Impact, supposedly caused by a meteorite, resulting in the death of half the population and the Earth’s axial tilt shifting. In this reality, a teenager named Shinji is thrust into the city of Tokyo-3, a militarized area located in one of the last dry parts of Japan. He is destined to become the pilot of the biomechanical mecha Evangelion EVA-01, the only weapon capable of fighting against the Angels – enigmatic beings attacking the city.

After the series’ original ending, the creator Hideaki Anno found himself submerged in letters from fans expressing criticism towards the conclusion of the story, some even making threats to demand a change in the ending. As a result, in 1997, the full-length film The End of Evangelion was created, regarded as the canonical, proper conclusion to the series. However, a detailed knowledge of the series isn’t necessary to watch the film. Its essence lies in its painterly depiction of death and destruction, combined with its dark poeticism.

The description above might suggest that Neon Genesis Evangelion is a typical action series rooted in science fiction. While it does possess those elements, it also has a second layer, a symbolic and more fatalistic side that the 1997 film delves deeply into.

After defeating the last of the Angels, a secret organization named SEELE aims to finalize the Human Complementation Project, which will trigger an accelerated evolution of humankind. However, events inexorably head towards the Third Impact, a catastrophe threatening the world. Aware of the impending disaster, the film’s characters gradually descend into madness. Hideaki Anno paints a demonic, unsettling vision of the end of the world in his film – aptly titled – infused with symbols from Christianity and Biblical references. Additionally, he embellishes it with psychedelic imagery reminiscent of a drug-induced descent. Towards the end, Anno presents viewers with a bleak image of destruction, surrounded by the characters’ somber dialogue on the inevitability of death, loneliness, and deceptive hope.

The series’ popularity, as well as the controversial ending, have led to various interpretations of the film, focusing on deciphering its intricate symbolism.

Barefoot Gen

Barefoot Gen is an intensely graphic and realistic account of a young boy’s journey through Hiroshima just after the atomic bomb was dropped on August 6, 1945. While the actual event was a catastrophic disaster on a massive scale, it wasn’t strictly an apocalypse, unless you view it from the perspective of Gen Nakaoko, who suddenly becomes an eyewitness to the end of his world. The viewpoint from which we observe the events is crucial. The main character, a six-year-old boy, leads a peaceful life in his hometown of Hiroshima despite World War II raging on. Unexpectedly, he’s thrust into a fight for survival in a city engulfed by the aftermath of a deadly explosion.

The anime presents the tragic consequences of this event in a brutal and impactful manner. It showcases an almost apocalyptic scene in Hiroshima, at times appearing as if it’s been lifted straight out of a horror film – melting bodies engulfed in flames, eerie shadows of burned people limping through the ruins of the Japanese city. At many moments, the film resembles more of a zombie apocalypse story than a documentary account of the 1945 events. Furthermore, the film’s tragedy is intensified by the fact that it’s told from the perspective of an innocent child, unaware of the magnitude of the tragedy he’s facing.

Barefoot Gen is an apocalyptic film in the full sense of the word, with a haunting and memorable atmosphere. Its somber aura is completed by the autobiographical thread. The film, directed by Mori Masaki and Mamoru Shinzaki, is based on the manga Barefoot Gen by Keiji Nakazawa, which is inspired by the experiences of the author, a Hiroshima survivor.

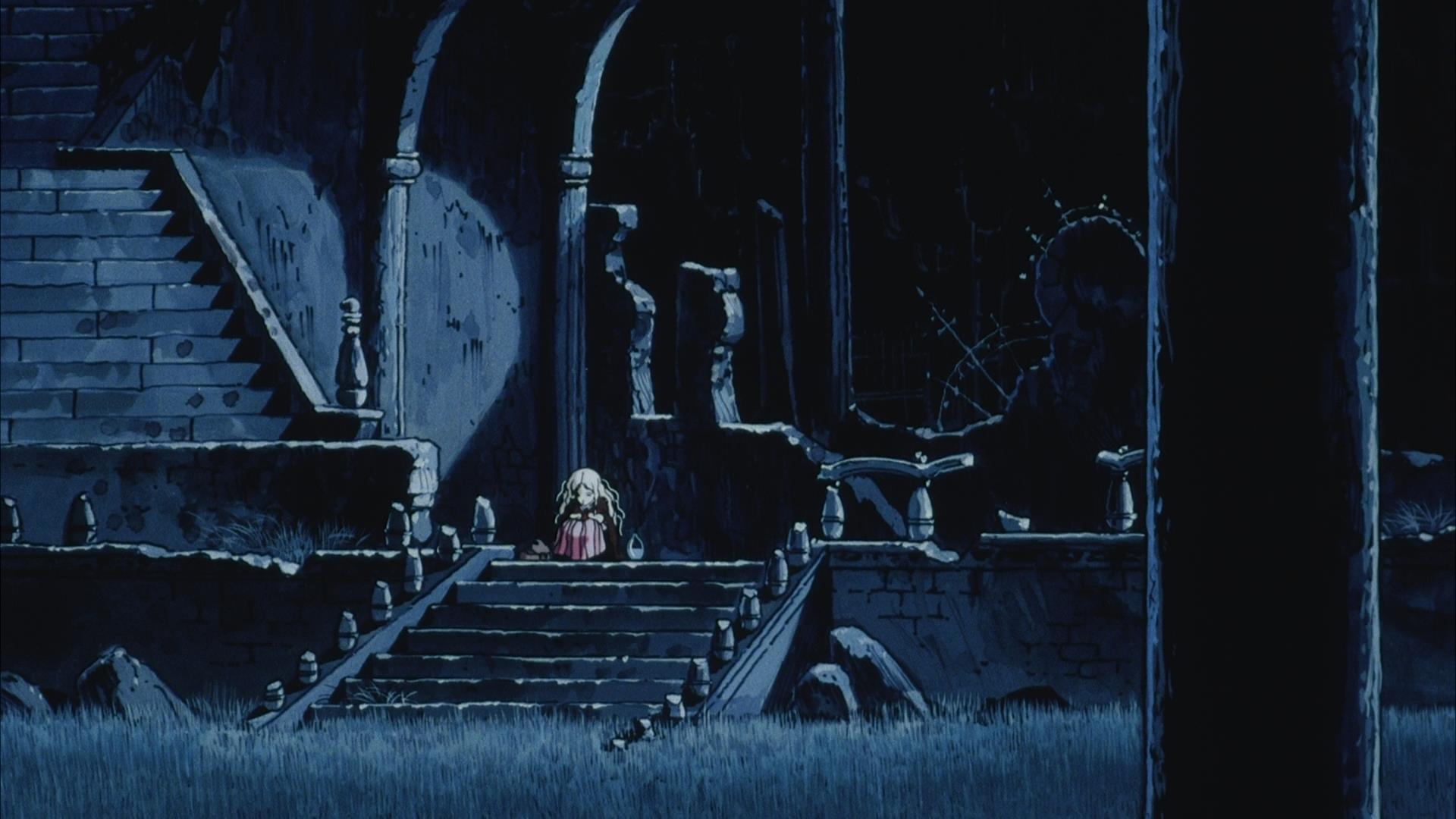

Angel’s Egg

Mamoru Oshii’s 1985 film doesn’t bear distinct characteristics of Japanese animation. It’s rather unique in itself. Extremely minimalist and sparing in visual elements, the film tells a deceptively simple story layered with meanings, symbols, and metaphors. The film transports the viewer to a dark, post-apocalyptic setting. The sole inhabitant of the desolate, barren, gothic land seems to be a girl with disheveled gray hair, seemingly accustomed to the prevailing darkness as she tends to a massive egg. Her companion in this journey of unclear purpose is an unfamiliar traveler, a boy with a stone-carved face, wielding a cross-shaped sword.

From start to finish, the animation maintains a Cassandra-like, dystopian, enigmatic style. Though nearly devoid of dialogue, a heavy Lovecraftian aura of the unknown persists in the air. At first glance, Angel’s Egg might appear to be a dull and unengaging tale. Indeed, it would be that way if the viewer doesn’t delve between the lines and attempt to decipher the numerous symbols. It turns out that Christian religion, the Bible, and particularly the tale of Noah’s Ark, serve as the interpretive key to the film, unlocking a series of new readings.

The director’s own life story sheds interesting light on the film. Mamoru Oshii spent years studying the Bible, a work that still remained exotic in Japan. Interestingly, the creator admitted that he began working on the film after losing his faith. Angel’s Egg is not a work created by a deeply devout individual – rather, it should be perceived as an attempt to ultimately confront faith or understand a world without God. It’s plausible that Angel’s Egg is nothing but a visualization of the creator’s existential crisis. A scream after losing something extraordinary, yet simultaneously reconciling with the fact that that something never existed at all.

Returning to the heart of the matter, the world depicted in Angel’s Egg is indeed a post-apocalyptic world, more precisely, a world where the biblical dove with the olive branch never returned to the ark. The tale of Noah’s Ark is incredibly significant here, and even the boy himself makes reference to it, speaking about the permanence of human memory. It tells of Noah who awaited the dove’s return in vain, eventually forgetting what he was truly waiting for. The ultimate confirmation of this interpretation comes in the final seconds of the film. The camera pulls away, revealing the shape of the island where the characters reside. This island eerily resembles an upside-down boat floating on the water. What does this signify? The world of Angel’s Egg is a world that never rejuvenated after the great flood. It’s a world abandoned by God, leaving humans to the illusion of hope. This film presents an incredibly bleak vision of the end of the world. An end that arrived before the world truly began. The richness of meaning compacted into such a modest work is a testament to the genius of Mamoru Oshii.

Akira

A title without which this list could not be complete. Akira is not only one of the most iconic anime, but also the epitome of Japanese apocalyptic science fiction. The film’s action takes place in 2019 in a new metropolis called Neo-Tokyo. It stands on the ruins of the destroyed Tokyo from 31 years prior, whose explosion marked the beginning of the Third World War. In the present, the city is engulfed in chaos and violence. Street gangs establish their own laws, frequent clashes occur between the police and anti-government militants, and religious fanatics await the return of a messiah called Akira. Beneath the surface of this dystopian city lies immense, incomprehensible power, in which only a few see hope for rebirth.

During this time, Tetsuo, a member of one of the motorcycle gangs, gets into an accident that awakens a mysterious power within him. Tetsuo falls under the observation of scientists, and when he escapes, his power grows to unimaginable proportions. Driven by anger and hubris, he becomes a deadly threat to the citizens of Neo-Tokyo. In his quest to find the more powerful Akira, he loses control over the power he possesses, becoming a ticking time bomb that threatens the city. The most vivid part of the film is the finale, where Japan’s fascination with destruction and annihilation reaches its peak. Tetsuo’s body, consumed by madness, transforms into a gigantic mass of twisted muscles entwined with blue-violet veins, releasing the dormant Akira—a force that destroyed the city years ago. This leads to an explosion of unimaginable power, causing not only the destruction of the city but also the creation of a new universe. Akira is a captivating spectacle, its power of destruction is truly staggering.

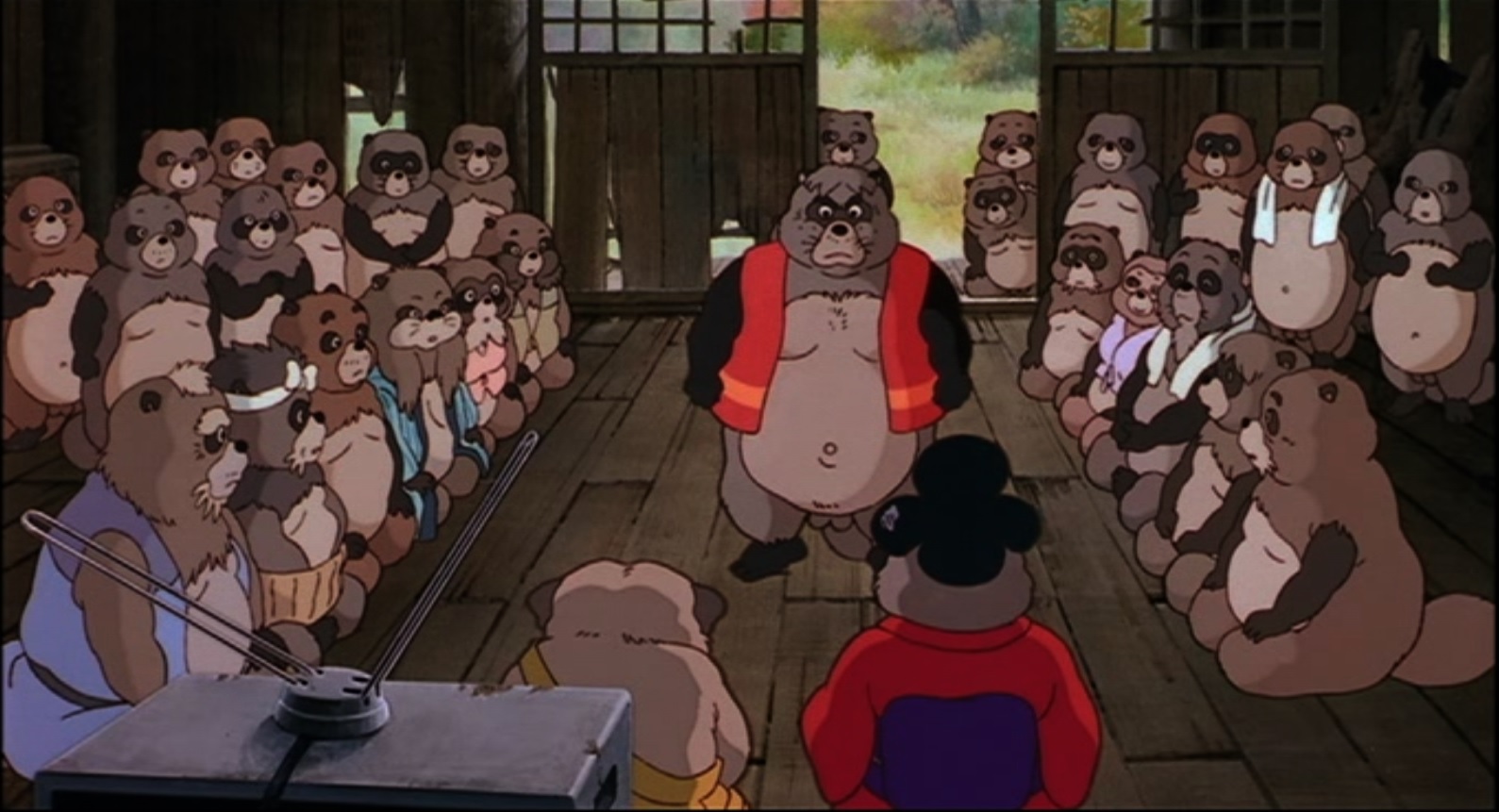

Pom Poko

I realize that the presence of this title on the list might raise some surprise. Pom Poko by Isao Takahata, another film from Studio Ghibli, is an animation that can be safely enjoyed by the youngest viewers. The story of brave, cleverly silly raccoons can bring genuine smiles to children’s faces. However, this doesn’t change the fact that adult viewers will extract the most contemplation from Takahata’s film. Above all, they will notice numerous references to Japan’s rich culture and beliefs, perceive a clear pro-ecological message, and understand the dire consequences that human greed and avarice can bring.

Pom Poko tells the story of a community of Japanese raccoons whose existence is threatened by a large-scale development project on the outskirts of Tokyo. Humans take over their natural habitats, causing the titular creatures to engage in an uneven battle for survival and self-determination. The raccoons join forces with other forest tribes, using various tricks to sabotage construction and drive humans out of their natural environment. The criticism of human greed and the message of respecting nature and its inhabitants are brought to the forefront. The film is witty and friendly enough that these lessons will even reach the youngest audiences.

However, if we were to look at the film’s plot from the perspective of the titular raccoons, we would be dealing with a strongly apocalyptic story. The main characters grapple with tragedy, in the face of which they not only lose their homes but also suffer a decline in their population. The gloomy ending leaves no illusions either. The raccoons fail to halt the spiral of human destructive activities, resulting in the disappearance of their natural habitat. The animals are confronted with a grim fait accompli, and their only chance of survival lies in adapting to life dictated by humans. As the raccoons adjust to life in the city among humans, the escape to the wild seems like a distant and blurry memory. Pom Poko is an incredibly somber story marked by suffering, where the end is marked by the necessity to come to terms with an unjust reality.