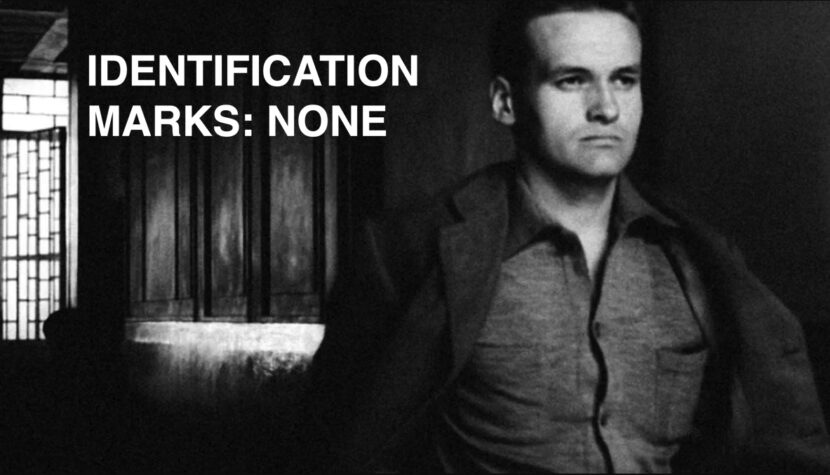

IDENTIFICATION MARKS: NONE. Enigmatic Debut by Jerzy Skolimowski

Or perhaps such traits are exclusive to sensitive individuals who cannot adapt to an environment governed by strict rules? Maybe those in power deliberately established such rules to filter out the more sensitive members of society, using the rest to the fullest because they are strong, loyal, and feel little?

Skolimowski’s debut is a film that is difficult both formally and intertextually. The director treated the viewer without leniency, making them feel literally like a failure. Indeed, it is hard to fully understand the content and form of Identification Marks: None.

On one hand, this could be attributed to Skolimowski‘s inexperience as a debut director and the fact that Identification Marks: None was created by merging his student film projects from his time at the Łódź Film School. On the other hand, it is not so obvious that Skolimowski lacked resources or the ability to tell Andrzej Leszczyc’s story differently—more accessibly. Considering the entirety of the Essential Killing creator’s work, I would lean more towards the latter thesis.

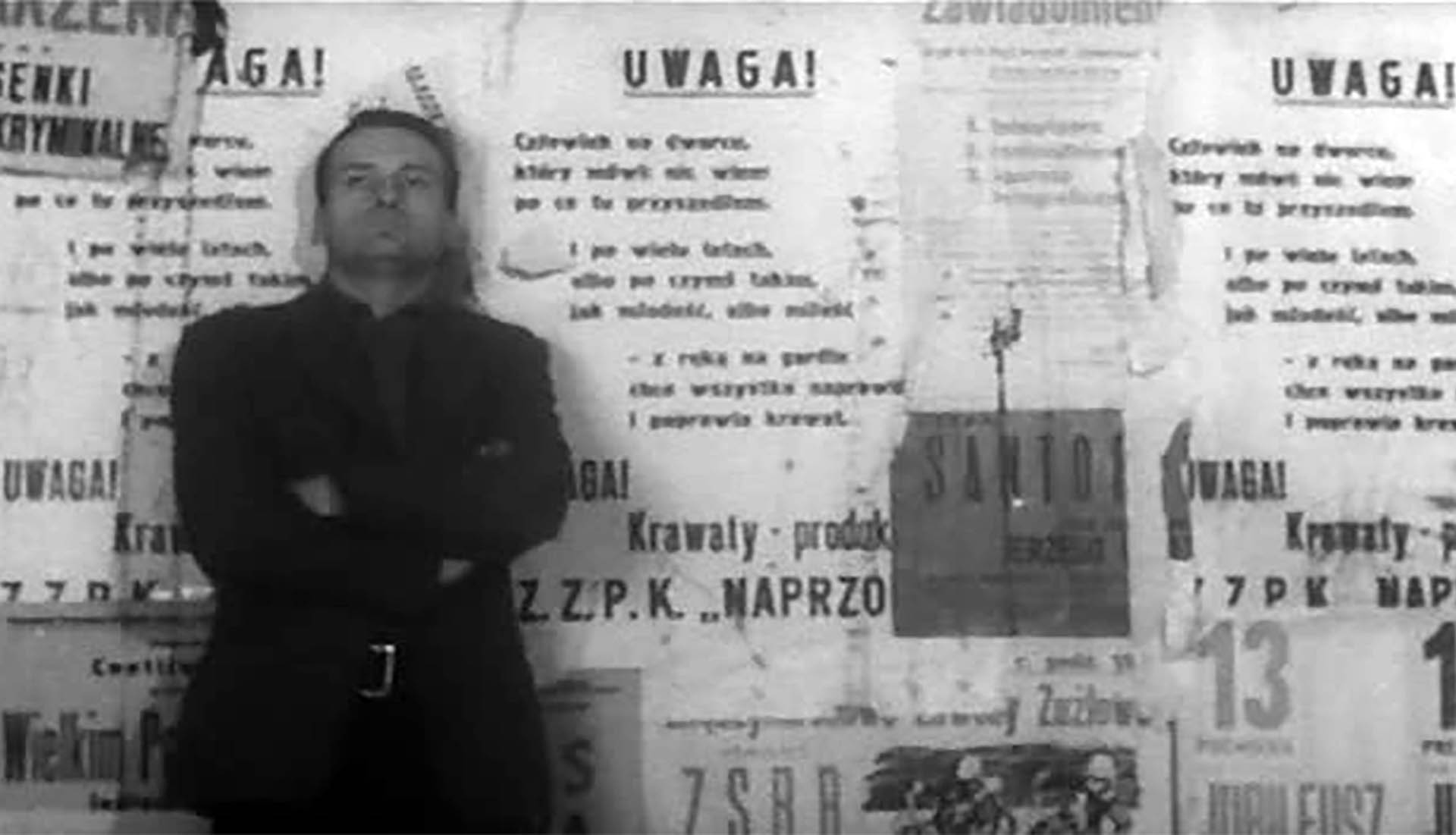

For Skolimowski in Identification Marks: None, the viewer essentially does not exist. Neither he nor any other film crew members are concerned with narrative clarity, matching music to the image, editing, the rhythm of dialogues, the actors’ diction, the logic of the story, lighting the set, or the role of the camera in a scene. The camera lens rather nonchalantly follows the actors, creating a clear emotional boundary between the depicted world and the viewer. The audience, therefore, must make a considerable effort to identify with anyone on screen, and our interest in a film or any visual art is usually generated through identification and finding common ground. Skolimowski says “no” to this.

He tells a story about an alienated hero, and the viewer must feel the same way. In this respect, the director was already standing out from his contemporary filmmakers. He was closest to Kazimierz Kutz and Andrzej Kondratiuk, and furthest from Andrzej Wajda. Wajda guided the viewer, never leaving them behind. Kutz, Kondratiuk, and Skolimowski, on the other hand, gave the audience so much creative freedom in interpreting the work that they could feel bored, offended, and unappreciated. Even the surreal Wojciech Jerzy Has took into account human perception and played on it. Skolimowski liked to stand somewhere between documentary transmission and a fictional story. Identification Marks: None is exactly like that. Its title also suggests that the work will always be unfinished in some deepest sense of its existence, both in content and form, just like the life of the main character. Remember, it was created when the French New Wave was beginning to wane for reasons mentioned above—viewers felt bored, overwhelmed, and confused by the radical freedom of artistic interpretation in modernist film productions.

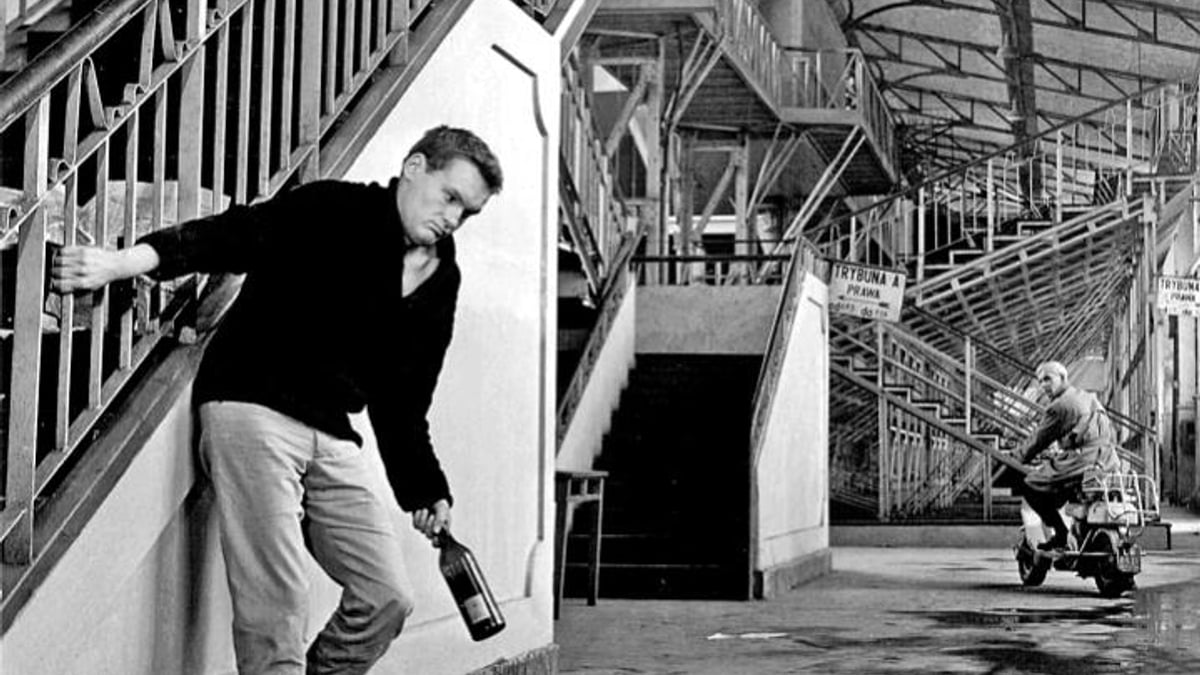

As I wrote in the introduction, Andrzej Leszczyc can be considered a failure or a loser, as today’s career-hungry, modern youth might say. However, this is the viewpoint of the strong, who do not necessarily understand why Andrzej is like that. Human behavior, even when objectively negative, always has its motives. Understanding them sometimes provides solid insight into someone’s nature, and although it does not always justify, it at least prevents blind aggression. One must, however, have the will to look at others this way. No one wanted to look at Andrzej this way in his life. His studies turned out to be a failure. Relationships with women also failed. The military, specifically the ideologically oriented Polish People’s Army, seemed like a way out. In it, Andrzej sought to numb his overly sensitive nature, as being a soldier, he would not have to think, analyze, or question the meaning. It would be handed to him on a plate.

Skolimowski rebelliously rejected such an attitude toward reality, although he allowed his protagonist, whom he played himself, to leave by train to Kołobrzeg. As we know from the director’s biography, he left Poland in 1969, thus, in a sense, he stopped fighting. Others stayed. The analogy with Leszczyc’s departure (escape) is therefore all too obvious, except that Skolimowski did not know it yet. However, he was an ideal candidate for such a reaction—sensitive, an artist, lost between multifaceted studies (Polish philology, directing, ethnography). In such cases, everything seems incredibly fluid. A victory can suddenly become a loss and vice versa. Again, it is up to the viewer to judge whether leaving on that mythical train to the army means submission or domination. Thus, a completely different side of Leszczyc is revealed to us. Yes, he was sensitive, slightly lost, sometimes egotistical, but he behaved this way because the environment was constructed in such a way that he did not fit into its artificially created mainstream nature. Who said that it is the individual’s nature that must adapt to the external world? Maybe it should be entirely the opposite, and only on the basis of quantitative arguments was it decided that the overly sensitive must toughen up.

The viewer also must, if they want to understand Skolimowski’s filmography. Because the point is to be able to give something of oneself, as the main character says. Apparently, he did nothing of the sort. Apparently, but all his struggling between ichthyological studies, women, and the military paradoxically requires enormous effort. Interestingly, a similar question can be asked of the director of Identification Marks: None. Did Skolimowski ever truly become a real filmmaker and devote himself to cinema as a profession, rather than as a kind of whim and hobby? Perhaps it is that film served him as a form of artistic expression in building his vision of the world constructed for himself, not for the viewer. And here lies the main issue—Skolimowski did not practice directing to satisfy the viewer’s entertainment needs. He treated film as a field of performative art in the strict sense. He stood somewhere between poetry, literature, painting, film, philosophical anthropology, but did not create an arena that a viewer craving proverbial bread and circuses could take possession of. French New Wave creators (including Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut) acted similarly. They created more with an eye on satisfying their own inventive ambitions than public expectations. This worked initially, but as we know from film history, the results of these methods were painfully verified by both viewers and, interestingly, critics.

A specific approach to narration and the excess of artistic ambition does not make Identification Marks: None an unwatchable, boring, and perfectly encoded film. If only one breaks through its form, one sees a moving story of a man told more through images than dialogues. One scene, in particular, is important when Andrzej tries to sneak into the apartment of the mysterious Teresa, who supposedly can be had almost on demand, and whose bust measurement is commendable. Leszczyc stands for a long time at the door, listening, wondering how to sneak in unnoticed, and suddenly a man with a white coffin for a baby passes him on the half-landing. In our culture, white symbolizes innocence, which includes a lack of experience. The child in this coffin did not have time to gain it, did not have time to live, and yet it died. For Andrzej, this means only and as much as that he is similar to the prematurely deceased child, with the difference that he does not want to start living. His existential coffin is his floundering between studies, women, lack of work. The military, however, seems like a salvation, the last one, because otherwise, there would be nothing left but a life of a bum.

Will it really be salvific for Andrzej the intellectual? One can doubt it, especially since even the major at the recruitment commission has no idea what that enigmatic ichthyology is. A pointed criticism from Skolimowski on the level of education in the People’s Polish Army.