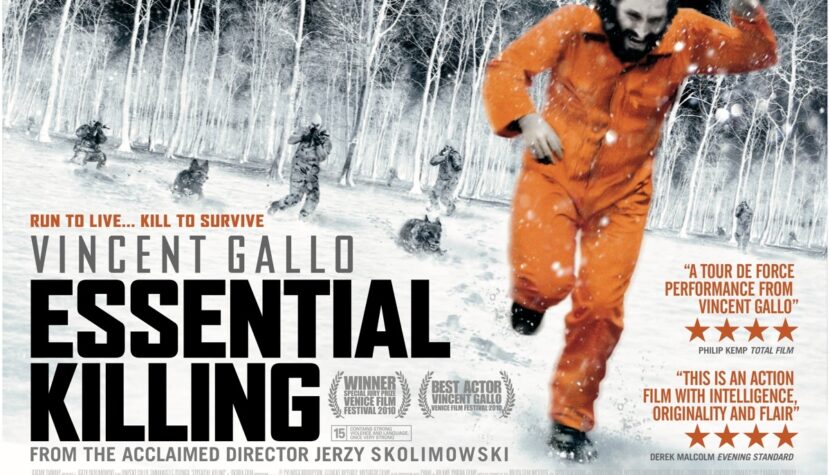

ESSENTIAL KILLING. A visually excellent unsettling thriller

It will be a radical counterpoint to the automatic applause for Skolimowski’s film. It will be a cool and subjective perspective, devoid of political or patriotic bias. Before I begin, however, I want to establish a few facts. I am not a film malcontent. Generally, I enjoy movies and approach them with a positive mindset. I appreciate artistic, poetic, and existential cinema, as well as Polish cinema as a collective entity of the aforementioned. So, this analysis is not an attack on this genre of film or the director. I want to be understood as an average, individual viewer with average film intelligence and taste in artistic cinema.

I watched Essential Killing an hour after the results of the Polish Feature Film Festival in Gdynia were announced – purely coincidental. However, I already knew that the film had been showered with Golden Lions from top to bottom, similar to the Venice Film Festival this year. As usual, I try to set aside such information during the viewing as festival awards can be influenced by political, industry, historical, or financial considerations.

So let’s focus on theEssential Killing itself and the story it tells. If we delve into the script, the plot is banally simple. Here’s Mohammed, an Afghan terrorist, captured by American forces in the deep Afghan desert. After a brief detention and torture at one of the U.S. bases in Iraq, Mohammed, along with a group of other prisoners, is transported to Poland, to one of the secret military bases. After a surprising convoy accident, Mohammed escapes into a snow-covered forest. From this point on, the plot revolves around observing the protagonist struggling with nature and the inept Polish military forces searching for him.

On paper, the story of Essential Killing looks downright banal and does not require further specification. Let’s look at the outline of the characters and the underlying theme of the script. Mohammed elicits our empathy for at least two reasons. Firstly, his appearance is not menacing. We know that in the desert, he killed three American citizens, but it was in self-defense. He had no escape route; trapped in a cave with no way out, he was terrified and essentially had no other choice. For us, he becomes a victim of the entire witch-hunt, a gray protagonist with a terrorist tint. Secondly, he is alone in a foreign country, surrounded by determined servicemen determined to kill him. Before our eyes, he loses the race against nature, which gives him little chance of survival in 20-degree frost. He is essentially the only character in the film, aside from a very short and debatable role by Emmanuelle Seigner, who helps him in a forest cabin.

Before we analyze Essential Killing and its events, let’s look at these elements. The script and characters are banally simple, even schematic – excluding the controversial topic of American torture and the secret CIA prison in Mazury, Poland (a topic very timely and increasingly based on facts lately). In the hour and a half escape through the Masurian-Norwegian forest (since the mountainous landscape in Masuria does not exist, it was doubled by friendly Norway), there’s practically nothing that would hold the viewer’s attention for more than 5 minutes. In the thriller genre, the film naturally loses to American cinema giants. A few incidents, such as falling into traps, encounters with loggers, or finding a cabin, are not plot twists that rivet us to our seats. The storytelling is simply dull. If this film is not intended as a thriller (by design), it must be something more. Mohammed’s story is just a vessel for a certain message that Skolimowski wanted to convey to us. Let’s examine that message. What can we deduce from the elements presented on the screen?

The main and only theme of Essential Killing is escape and the struggle for survival. Man is an animal driven by instincts, and the survival instinct is one of the strongest, although rarely experienced. We do not have the opportunity to understand this until we find ourselves in an extremely crisis situation. Here, the protagonist proves this fact throughout his journey towards survival in the freezing Masurian forest. However, it is not a black-and-white journey. Even though he had the chance to shoot a moose that would provide him with essential protein for survival, he refrained from doing so. He did it consciously, and I believe it was a matter of conviction (this aspect is absolutely untouched by the director). He also declined food in the cabin, although he was bandaged and given dry jackets. His will to survive is selective, based on principles, and certainly not schematic. If we already have the will to survive, what else is there? Rare retrospections suggest that Mohammed is a strongly religious man, which is, of course, the basis for Middle Eastern terrorism. However, we do not know how fanatically he was connected to the idea of terrorism. We know that he led a modest life, had a wife and child. The visions haunting him reinforce his unwavering belief that he will never see them again. But his character is strong, as are his principles and instincts. He realizes that death is near but is not scared – he is rather overwhelmed by the hopelessness of the situation with no way out.

So, can Mohammed be a hyperbole of terrorism? If we use him as a metaphor – will Essential Killing then be full-fledged? If we delve into further analysis, we could view Mohammed as an everyman – a universal human. It is a rather controversial and far-fetched view, but observing a stranger in Polish landscape suggests a certain thought. A Polish viewer might catch themselves comparing – how would they behave in such an extreme situation? A non-Polish viewer probably wouldn’t make such a comparison, as the Masurian landscape is as distant to them as the Afghan landscape. For us, however, the exaggerated, caricatured Polish characters, Polish language, and surroundings bring us somewhat closer to home. They prompt thoughts – what if it were me besieged in the Afghan desert, in a landscape unknown to me before, condemned by nature to a slow death? The terrorist Mohammed becomes only a catalyst for events. In such an extreme situation, the line between a terrorist and a civilian can blur. While this comparison is controversial, it is also mundane and stretched.

Death, the will to survive, animosity, hopelessness, a race to nowhere, agony, and violence. Would anyone dare to publicly say that we are dealing with a cinematic cliché? With a set of worn-out phrases, repeated on screen with unloved regularity? I don’t want to be misunderstood, and that’s why I didn’t end the analysis at this point alone. Analyzing the “microenvironment” of this story is not sufficient for me. It does not provide satisfaction or confirmation that the film deserves all the praise. So, I tried to look at it from the perspective of the “macroenvironment.” What if the protagonist of Essential Killing embodied terrorism as an idea of a military movement? Elusive, yet eternally pursued by inept international armed forces. Capable of surviving all adversities and willing to resort to ultimate measures to stay alive. Living like a weed nurtured by others, but with fundamental principles and iron rules. Resilient and determined, yet his death will be as poetic as unnoticed. Can Mohammed be a hyperbole of terrorism? If we use him as a metaphor – will the film then be full-fledged? The answer is not required. What matters is that I, as an inquisitive viewer, need to seek additional interpretations for the film to make sense and hold value. My hyperbole does not stem from the film’s plot itself. I added it personally to derive pleasure from the film. It’s just an analysis, a film discussion, and savoring cinema as such.

So here’s the question: Is it necessary? To understand the motives of Gdynia or Venice, do I need to answer the question, “What did the poet mean?”? Does assigning meanings and interpretations to the film give it value and weight? I don’t know. I believe it’s not fair. Overinterpretation is harmful. Turning The Matrix into biblical commandments and proving that it is a story based on the Bible is unjust. There are always such reviewers popping up like mushrooms after the rain right after the premiere of another milestone in the history of cinema. If the director does not give us permission in their film, if they do not provide a sign or hint, attributing meanings and interpretations to the plot is somewhat deceitful. If the film tells us something is black, it’s unfair to analyze and prove that it’s white.

Therefore, I assert that overinterpretation has lost Essential Killing. On the microenvironment level, the analysis of events is not a sufficient reason for me to consider this film great. I am not afraid to say that it is a film full of clichés and existential banalities about fear, the power of survival, and human instincts. Only after adding a new dimension to it (Mohammed as the idea of terrorism) did I feel that this film gave me some enjoyment. It also satisfied me aesthetically and visually – beautiful shots, very good editing, and a great character played by the controversial Vincent Gallo (who didn’t utter a word here). I don’t know if this was a counter-review. Nevertheless, the film evoked mixed feelings in me, with a predominance of negative ones. It also garnered mixed reviews despite being showered with European awards. It’s not about proving who is right. Festival directors or festival audiences. Western reviewers or Polish reviewers. Everyone has their cinema, and I feel lighter now.