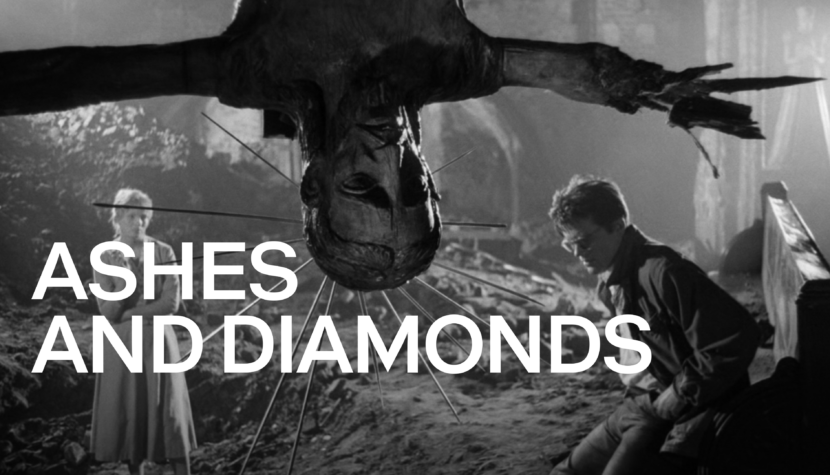

ASHES AND DIAMONDS. Andrzej Wajda’s Timeless Masterpiece

It can be said with great probability that almost everything has already been written about it (it is also the only Polish film to have received its own extensive monograph by Krzysztof Kornacki). The following is a chaotic collection of trivia and basic information, behind-the-scenes anecdotes, and various facts about Wajda’s film, which any lover of Polish cinema should delve into.

Ashes and Diamonds is a MASTERPIECE, not only of Polish but also of world cinema. What electrifies when reading reviews, writes Krzysztof Kornacki, is the courage and frequency with which authors use terms like “masterpiece,” “genius,” “outstanding,” “excellent,” “groundbreaking”; sometimes right in the title, which – in the case of film criticism – constitutes the highest expression of praise. Never before had such a bouquet of superlatives been used in relation to a Polish film. This can be summed up by saying that Polish cinematography had not produced too many outstanding films before. But from the perspective of a historian of Polish cinema, I can responsibly state that even later, terms like those used for Ashes and Diamonds appeared very rarely.

The international scope and prestige of Wajda’s film (sold to forty-two countries in its first decade) is evidenced by the excellent press it enjoyed abroad (for example, the London weekly New Statesman called it the best film made after the war, while the Parisian Le Monde praised the talent of Wajda and other directors of the Polish Film School). Ashes and Diamonds also received two international awards – the FIPRESCI Prize at the Venice Festival and the Silver Laurel, an award funded by American producer David O. Selznick for films that, “due to their high artistic level, contribute most to strengthening the bonds of friendship and mutual understanding among the nations of the world.”

The best proof of the extraordinary impact of Wajda’s film can also be the statements of artists, such as Andrei Tarkovsky’s words: “Ashes and Diamonds was a revelation for us, for many of us,” or the confession of Japanese director Kohei Oguri, who became a filmmaker under the shock that the screening of the Polish film caused him. However, among foreign directors, there is no greater admirer of Andrzej Wajda than the Italo-American master Martin Scorsese, in whose films one can find many inspirations from the Pole’s cinema (for example, Scorsese’s Taxi Driver borrows heavily from Ashes and Diamonds and Carol Reed’s The Third Man). Sławomir Bobowski, in his book “Between Sanctity and Condemnation. Martin Scorsese and Religion,” recalls a charming episode from Andrzej Wajda’s life, as related by Piotr Lis:

Wajda showed the Oscar-nominated The Promised Land in America, and an unknown man approached him. “My name is Martin Scorsese,” he said. “I saw your Ashes and Diamonds. Wonderful. My film Taxi Driver will be shown shortly. In the final scene, the hero wears dark glasses…”

Bogumił Kobiela, who plays a role in Wajda’s film similar to that in Bad Luck (which came two years later), the role of an opportunist and scoundrel – Julek Drewnowski, the president’s secretary. Kobiela, along with the brilliant Stanisław Milski, who plays the editor Pieniążek, creates an unforgettable comic duo reminiscent of the dramas of William Shakespeare, offsetting the tragic accents of the main plot. The story of Kobiela’s entry into the film is very prosaic: “Kobiela followed Cybulski,” explains Andrzej Wajda, referring to the friendship of the two artists, tireless activists of the Gdańsk student theater “Bim-Bom.” Kobiela’s attitude towards work and his new role in Ashes and Diamonds is evidenced by this short fragment of a letter he sent home before the start of filming:

I have offers for three films. In the meantime, I was going to Łódź every week for The Assassination of Kutschera, and I’m also scheduled with Has for a small but great episode in Farewells by Dygat. This is not the end, because – attention! attention! – I’ve already signed a contract for a big role in Andrzejewski’s Ashes and Diamonds! I’ve negotiated a lump sum – 20,000 zlotys! I’m going on Monday for the first shots and I’m as happy as a child.

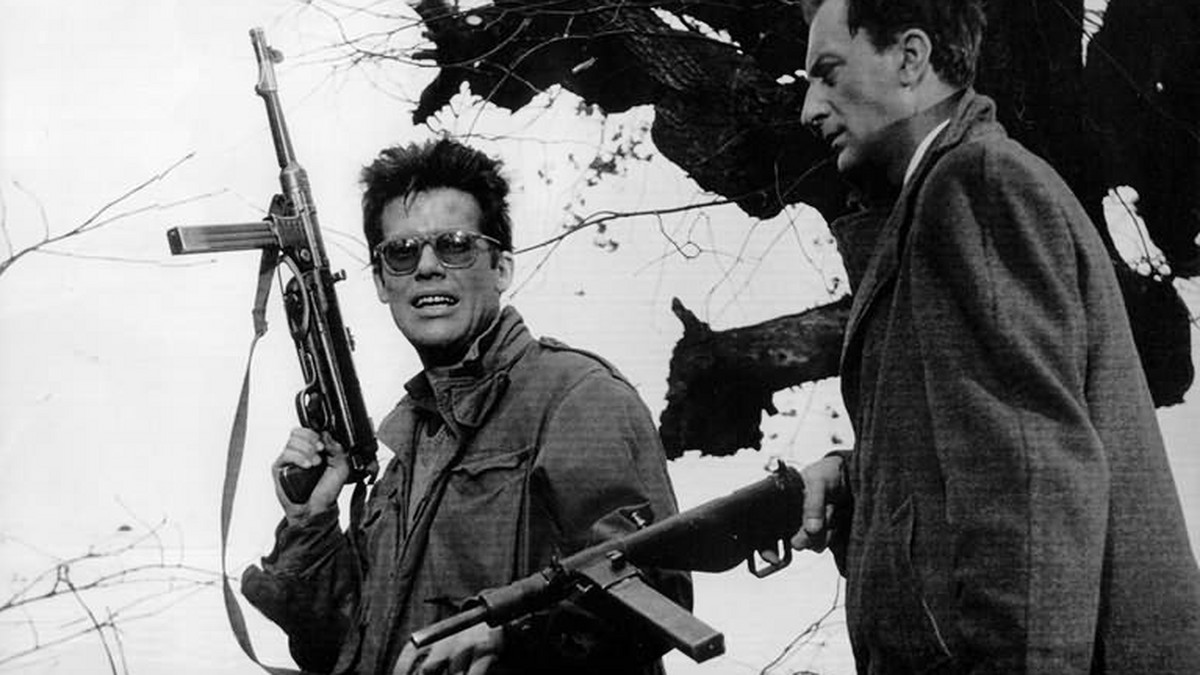

Zbyszek Cybulski, delivers the most important role of his career in Ashes and Diamonds. The Polish James Dean would never escape the character of Maciek Chełmicki. This role would become both a curse and a blessing, as well as a monument. To illustrate his situation, Cybulski often recounted an anecdote about a fan who, after the premiere of How to Be Loved (where Cybulski attempted to deconstruct his own myth by playing an anti-Chełmicki), stood up during a meeting at Warsaw’s Reduta club and asked, referring to a scene in Has’s film: “If, in real life, a woman was being raped in the next room, would you hide under the mattress too?” This is the most telling proof that it wasn’t the hero – Maciek Chełmicki – but his portrayer Cybulski who became a national symbol of generational trauma, forever merging in the minds of viewers with the image of a Home Army soldier in dark glasses (the burden of this generational symbol was so keenly felt by the actor that he named his own son Maciej). It is hard to imagine today that someone else, like Tadeusz Janczar, whom Wajda considered, could have played the role of Chełmicki. Wajda initially did not want to cast Cybulski, believing he was difficult to work with. He relented only when Janusz Morgenstern – the assistant director of Ashes and Diamonds – threatened to leave if Wajda did not cast Cybulski as Maciek. It should be noted that Morgenstern had his own interest, as he wanted to cast Cybulski in his debut Goodbye, Till Tomorrow, and the long shooting period for Ashes and Diamonds was a great opportunity for simultaneous preparatory work.

LOWER SILESIA, where the film was made – more precisely, at the Wytwórnia Filmów Fabularnych No. 2 in Wrocław, where the set of the Monopol hotel was built, where most of the action takes place, unlike in the literary original. Ashes and Diamonds is a studio film (less than 20% of the footage was shot on location). The crew lived on set during filming, i.e., in the rooms of the Wrocław studio. Sometimes they filmed in slippers and bathrobes, and rehearsals were organized at various times – for example, in the middle of the night. As a result, the atmosphere on set was homely and familial, and at times even – as Kornacki describes it – banquet-like. Regarding the interiors used outside the sound stage, filming took place in two locations: in the then-partially demolished Church of Saint Barbara (today functioning under the name of the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary) and in a corridor imitating the Security Office in scenes with Marek Szczuka. For the May location shots, picturesque streets of Wrocław were used (e.g., one of the walking scenes with Cybulski and Krzyżewska was filmed on Franciszkańska Street) and the Chapel of Saint Hedwig near Trzebnica, where the assassination scene that opens the film was shot. The death scene of the main character on the “garbage heap of history” also deserves mention; this garbage heap was played by a landfill in the Krzyki district, where Władysław Anders Mound stands today.

The entire process of making Ashes and Diamonds, despite the ongoing thaw, was hindered by state censorship. However, this does not mean that Wajda’s troubles with the authorities ended permanently after the film’s premiere. Six months after Ashes and Diamonds hit Polish cinemas, officials faced a serious dilemma: could Wajda’s ideologically ambiguous work be sent to the Cannes Festival? The director was given a choice: either he significantly shortens the final sequence with Maciek’s “death dance,” or the film would not represent the country at the most important European festival. Wajda did not yield, and the film was not submitted, which greatly disappointed Favre Le Bret – the festival director. A few months later, the fight to send Ashes and Diamonds to international festivals resumed; there was a desire to send the film to Venice, but this plan also failed, though not entirely… Ultimately, the Polish delegation took Wajda’s masterpiece to Italy, securing permission to show the film in the informational section, i.e., out of competition. How great was the surprise of state officials when Ashes and Diamonds returned to the country with the International Federation of Film Critics (FIPRESCI) award, which – unbeknownst to anyone in the party – could be awarded to any film regardless of whether it was in competition or not.

Wojciech Fangor designed the poster promoting Ashes and Diamonds in 1958. The piece strikes with its austerity for a very simple reason – it was composed hastily, in a single night, due to the pre-premiere frenzy, as the director himself put it. Despite the recognition Fangor enjoyed within the Polish School of Posters, his work was harshly criticized, among others by Tadeusz Kowalski in the magazine “Film” (1958, No. 42, p. 5):

It’s a great pity that Wajda’s ambitious and formally excellent film did not get a more interesting poster. Wojciech Fangor’s composition is related to ‘Ashes and Diamonds’ only by its title – nothing more. Simplicity of means means eliminating unnecessary elements, not simplification leading to emptiness. This poster, with a different title inserted, could equally well advertise a comedy, drama, or travel story.

Ultimately, the artist was brought down by a sixteen-year-old boy who sent his own poster design to the editorial office of Film, sketched on a yellowed piece of paper with the note: “Although I am 16 years old, I think this ‘poster’ is better than the current one. ‘It says more.'”

From the very beginning, Chełmicki’s girl caused the most problems. Wajda couldn’t manage to cast this role, so filming started without her. They shot scenes without Krystyna while searching for a young, pretty, and natural non-professional actress. The casting problem even made it to the press, resulting in a series of articles, including in the Łódź Express Ilustrowany, which wrote:

Everyone is looking for Krystyna. They are examining dozens of women coming to Wrocław, but none of them is Krystyna. Yet everyone knows her well. She’s the one Maciek fell in love with and for whom he wanted to start a new life…

Finally, Ewa Krzyżewska, a first-year acting student in Krakow, was cast. Unfortunately, problems with Krystyna-Krzyżewska had only just begun. She didn’t get along with Cybulski, and Wajda was dissatisfied with her performance. While shooting the prologue in Trzebnica, observing the little girl who in the film asks Kossecki for help, the director sighed: “If only our Ewa acted like this little one…” Krzyżewska was introverted, distant, and confused. Additionally, she got involved in an unhappy romance with one of the Wrocław actors, leading to distraction and even running away from the set. Years later, Krzyżewska recalled:

Wajda somehow wonderfully utilized my confusion. That the role of Krystyna was well-received is mainly thanks to Wajda and my partner Zbyszek Cybulski.

Ewa Krzyżewska never made a film career, but she went down in history as Krystyna from Ashes and Diamonds and even received the French Film Academy’s “Crystal Star” award for this role in 1962.

Hanka Lewicka’s song (performed by Grażyna Staniszewska with Sława Przybylska’s dubbed vocals) functions independently in Andrzejewski’s novel from Maciek and Andrzej’s memories scene. However, the filmmakers decided that both the Lewicka scene and the Home Army soldiers’ memories were too static, too “literary,” so they made radical changes. They combined both scenes into one, reduced and modified the dialogues, and added an element that would become famous worldwide – the spirit lamps that Maciek lights under Andrzej’s direction: “Haneczka, Wilga, Kosobudzki, Rudy, Kajtek…”. The scene was created after hours of brainstorming, though if we believe Wajda, the glasses were Morgenstern’s original idea. Since regular spirit burned with too weak a flame, almost invisible on film, glasses filled with gasoline were used (which is why Cybulski had to maneuver the glasses carefully to avoid drinking gasoline by the end of the scene). The difficulties of the realization are also evidenced by one of Wiesław Zdort’s photos, showing a substantial battery of matches lying under the famous bar counter. Krzysztof Kornacki deemed this scene the most important in the history of Polish cinema. It was probably shot on April 11, 1958, and took two days to complete.

Andrzej Wajda is a director who thinks in images. The main emphasis in his films is on the visual aspects, photography, composition, and staging. This is perfectly visible in Ashes and Diamonds. When we hear Ashes and Diamonds, the associative reaction is instantaneous – “the scene with the glasses,” “the assassination of Szczuka scene,” “the scene with the inverted cross,” “the polonaise scene,” etc. We think in scenes because they are characteristic and skillfully executed. This is thanks to the crew members responsible for the film’s visual side: Roman Mann and Jerzy Wójcik, as well as Krzysztof Winiewicz (camera operator), Bogdan Myśliński (camera assistant), Zygmunt Krusznicki (lighting master), Jerzy Szurowski (focus puller), Wiesław Zdort (photographer), and also Jarosław Świtoniak (assistant set designer), Leszek Wajda (interior decorator), and Aleksander Ciapała (props master).

Jerzy Andrzejewski’s novel Ashes and Diamonds was published in 1948. Previously, it had been serialized in the weekly Odrodzenie under the title Right After the War. Even in 1957, Andrzej Wajda was unfamiliar with Andrzejewski’s book, despite its reputation as one of the best post-war novels.

I was being treated in Krynica (a duodenal ulcer I developed after the film Kanal). I met Janczar there. During a joint mountain trip, he told me the story of Ashes and Diamonds, which I hadn’t read. And Janusz Morgenstern, who was my assistant on Kanal, added that there is a wonderful scene – a polonaise danced at dawn on the eve of the end of the war. I read the novel.

Ultimately, Wajda’s film differs significantly from the book, although Andrzejewski himself was the co-writer of the film’s screenplay. A fundamental difference was limiting the action to one night and making the Monopol hotel its central setting.

Our second Jerzy [Wójcik] wrote in his book Labyrinth of Light:

In 1948, I watched Citizen Kane in Wałbrzych. It was a very strong experience, after which it was hard for me to return to reality. Basically, this film decided that I became a cinematographer.

Gregg Toland’s cinematography – Orson Welles’ go-to cinematographer – was a model for Wójcik in Ashes and Diamonds. The most important techniques used by the Polish cinematographer (sometimes literal citations from Citizen Kane) include deep-focus shots (achieved with wide-angle lenses) and low camera angles (deliberately presenting elements of Mann’s set design, such as ceilings). Another influence on Wójcik’s cinematography was Carol Reed’s film The Fallen Idol and the neo-expressionist style of its cinematographer Robert Krasker:

“We weren’t blind to other great western cinema – including British cinema. Carol Reed’s The Fallen Idol became our artistic gospel and an unattainable model,” recalled Andrzej Wajda years later.

Jerzy Wójcik imitated Krasker mainly in the realm of lighting. The British cinematographer’s technique stood out due to strong chiaroscuro contrasts and directed light streams. In Ashes and Diamonds, there is no room for grays – the shots are black and white, strongly contrasted both visually and symbolically. Excellent examples of Wójcik’s use of directed lighting include the beam of light pouring through the counter window in the farewell scene with Krystyna or the scene of the hotel porter hanging the flag.

CROSS. This refers to the figure of Christ, which in the church scene – in the foreground – hangs upside down, dividing the frame into two parts. It is one of the most important props in the tradition of our cinema not only because of the characteristic aesthetics it lent to the most recognizable shot of Ashes and Diamonds but also because of the symbolic values it carries. It is like a “third actor” in this scene (although critics unjustly complained about overly intrusive props that steal the viewer’s attention from the actors). One could say that the famous shot summarizes the entire film and serves as its poignant synecdoche – Christ, symbolizing sacrifice and self-sacrifice, separates the cursed Home Army soldier from the girl, who represents the promise of a better life. The figure was cast in plaster and can be admired today at the Museum of Cinematography in Łódź.

In Ashes and Diamonds, art triumphs over life. There are many examples in the film of bending the laws of physics, sometimes for the sake of spectacular effects, sometimes for scenic attractions, and other times for added meanings. For example, the jacket of one of the workers killed in the prologue catches fire from Maciek’s shots. As we know from the accounts of the crew members, the flames erupted quite by accident. Most likely, the spirit used in the blood paint caught fire, but the effect was so spectacular that the shot made it into the film. Another matter is Mann’s set design, characterized by a complete lack of functionality – abandoning spatial logic in favor of fanciful lines and breaks, amusing the viewer with unusual arrangements (for example, the basement bar room, which, if you look closely at the interior layout, should be on the ground floor, although we would then lose the great dialogue scene between Maciek and Andrzej at the counter window). Also interesting is the anachronism of the main character’s attire. Initially, Maciek was supposed to look like his literary prototype, a typical young man living in 1945. He was supposed to wear tight breeches and high boots, like most young Home Army boys. However, when Cybulski appeared on set, he refused to wear the costume. His dislike of costumes was well known, so after long arguments and negotiations, Wajda capitulated, and Cybulski played in what he arrived in – an American M65 jacket, white shirt, jeans, pioneer boots, and dark glasses that he wore every day. For the glasses, a neat, almost symbolic explanation was found – they became a “memento of unrequited love for the homeland.” Cybulski in Wajda’s film is dressed like a young man of the late 1950s, which did not escape the critics’ notice. They saw in this device a sort of intergenerational link, through which the events depicted in the film gained unprecedented power of influence on the contemporary audience.

The editing virtuosity of Ashes and Diamonds hides under the concept somewhat paradoxical – the concept of intra-frame and intra-scene montage. Paradoxical because the mentioned types of montage are based on techniques that do not require cutting, which is a necessary element of editing in the strict sense. This specific type of editing is based on the composition of the frame, i.e., it utilizes the depth and multi-planarity of the frame/shot, “editing” individual scenic units already at the level of shooting, without the post-production intervention of the editor’s scissors. This technique was used by Greg Tolland in the production of Welles’ Citizen Kane, which, as we have already noted, became a professional revelation for Jerzy Wójcik. One of many examples of similar shot constructions can be the scene where Kossecki calls Major Waga; in the background, we see Maciek leaning against the reception desk, and in the third layer, the head secretary Szczuka enters the lobby. This Western style of intra-frame and intra-scene editing clashed with the techniques of the Soviet school of montage, such as those of Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin, in Wajda’s work. This refers to associative montage, which by juxtaposing individual images – be it shots or scenes staged within a shot – constructs added meanings on the screen. An example of this can be the scene with the cross, or another scene that projects a similar antithesis: Maciek talks to Andrzej at the reception window, then looks towards the bar, the cut to Krystyna behind the bar, Maciek looks out the window, another cut to tanks passing by outside the window. In this way, a metaphor for the internal conflict of the character is constructed – torn between love and duty.

Krzysztof Kornacki also points out many editing mistakes, resulting sometimes from improvisation on the set, for which Wajda is known, and sometimes simply from sloppiness, for which – unfortunately – Wajda is also known. An example can be the scene of the assassination attempt on Szczuka, where Maciek unexpectedly appears in front of the secretary, which in comparison with the previous shot, showing the Home Army soldier departing from the hotel, comes across as illogical and disorienting.

Cyprian Kamil Norwid’s poem – Ashes and Diamonds – inspired Jerzy Andrzejewski. In the church scene of the film, Krystyna finds a plaque with a Norwid inscription, containing the main question of the film – about the meaning of sacrifice:

Will the ashes only remain, and the turmoil

Going to the abyss with the storm – or will there remain

In the bottom of the ash a starry diamond,

The dawn of eternal victory!

A Renaissance, marble plaque was used in the scene (still existing today in the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary), covered with a plaster plate with the octet text.

MUSICAL design was done by the Polish Radio Rhythmic Quintet under the direction of Filip Nowak, who also led the fictional Monopol orchestra (the man in a white jacket, visible in the film). In Ashes and Diamonds, there is no so-called non-diegetic music, i.e., music heard only by the audience (with the exception of the opening credits, where war songs are played on an ocarina – Hey Boys and Autumn Rain – and the end credits, i.e., the polonaise).

On the soundtrack, we hear instrumental versions of, among others, François’ Waltz, the songs Dark Eyes and Golden Chrysanthemums, as well as well-known waltzes (including Wienerblut), polkas, mazurkas, and tangos. In the procession scene of Kotowicz, the A-major Polonaise (“mangled – as Iwona Sowińska wrote – by the pub band”) and the polonaise Farewell to the Homeland by Kleofas Ogiński were used. The latter will also be heard in the end credits of the film – as Krzysztof Kornacki writes in his monograph.

Of course, the most important song of of Ashes and Diamonds, which we hear in the shot glass scene, is Red Poppies on Monte Cassino performed by Hanka Lewicka. Wonderfully nostalgic, touching, and proud, it puts Maciek in a melancholic mood and serves as a perfect illustration for the scene of reminiscing about better times, when “life was lived and in what company.” Music in Wajda’s film also serves as the diegetic clock. Surprising is the consistency with which the continuity of the soundtrack, synchronized with individual scenes, is maintained, creating the illusion of spatial and temporal unity of events taking place at the Monopol hotel. This is perfectly visible in the bedroom scene, where with each cut, a piece played by the orchestra on the floor below changes, signaling the passage of time.

PREMIERE of Ashes and Diamonds which took place on Friday, October 3, 1958, at the Moskwa cinema in the capital. Still on the day of the premiere, Wajda received a phone call from a censor who demanded the removal of the final scene at the garbage dump from the film. The director did not yield, knowing that no one would tamper with the shape of his work after the first screening. Jerzy Andrzejewski writes in his diary:

Monday, 6.10.1958 [author’s mistake – MD]. In the evening, at the premiere of Ashes and Diamonds, then at Spatif and even later at the Bristol nightclub. Wajda disappeared first, to make it to Zegrzynek, where he had been shooting the first scenes of Lotna for several days. […] A little disturbing that everyone praises the film so unanimously.

After the Warsaw premiere, local screenings were organized in larger cities, often with the participation of crew members (e.g., the premiere at the Coastal Students’ Club Żak, important for Cybulski due to his sentimental attachment to the Tri-City). An important date was the screening in Wrocław’s Hala Ludowa, located a few dozen meters from the Film Production Company, where the film was made. Jerzy Wójcik recalls:

A grand premiere screening of “Ashes and Diamonds” was organized at Hala Ludowa in Wrocław, which can accommodate tens of thousands of spectators. Andrzej Wajda, the actors, and I, among them, were placed on the central stand embedded in the audience. After the screening, spotlights lit up directed towards us, but also towards the audience. I saw… tens of thousands of pairs of eyes that turned and looked at us. I cannot forget that. It was an enormous shock, but also a feeling of happiness that I witnessed an event that is incomprehensible to me. When I start to think that several million people watched the film because many of my films were shown on different continents, I cannot grasp that. However, when I saw tens of thousands of pairs of eyes that looked at us, I felt an overwhelming surge of energy. I felt like something lifted me up, propelled me into space.

ROMAN Polanski was considered for the role of Marek Szczuka – the son of the PPR secretary. If Polanski had gotten this role, it would have been his greatest performance at the time. Eventually, Jerzy Jogałła played Marek Szczuka excellently – with a bite, yet melancholically and conservatively.

In post-war Poland, there were several good set designers, but only two were absolute masters – Anatol Radzinowicz and Roman Mann, who created the set design for films such as The Last Stage, Youth of Chopin, Adventure at Mariensztat, Cellulose, Under the Phrygian Star, Man on the Tracks, Ewa Wants to Sleep, Cross of Valor, Knights of the Teutonic Order, Mother Joan of the Angels, and Andrzej Wajda’s war trilogy, namely A Generation, Kanal, and Ashes and Diamonds. Radzinowicz was incredibly orderly, disciplined, and responsible. But there was also Mann, whose line had a magical power. Both were great, but what different artists they were. One director favored Radzinowicz’s hard and strong style based on professional craftsmanship, but a hard and heavy hand. And another favored Mann – as the set designer Lala Blaszyńska recalled.

Jerzy Groszang characterized Mann’s style of work and personality:

Mann was characterized by impeccable taste, refined color sense, and a certain artistic nonchalance. He wasn’t a workhorse; he appeared like a butterfly, creating the fundamental shape and then disappearing like a butterfly, leaving the rest to the “personnel.” His designs were often autonomous works of art.

So on one hand, there was Radzinowicz – the tireless craftsman, and on the other hand, there was Roman Mann – an artist in the modernist sense, who disregarded harmony, logic, and orderliness, and focused on expression and atmosphere. All spatial inconsistencies and the anachronism of the Monopol set design stem from this “artistic nonchalance.”

Ashes and Diamonds is a goldmine of excellent and iconic lines that stick in the memory after the first screening. It’s enough to recall the excellent character of the banquet jester, Editor Pieniążek, in a drunken frenzy throwing his wisdom left and right (“The minister’s health is a business drink,” “Shit always floats to the top,” “Poland has exploded for us!”). The medal for sharp retorts, however, belongs not to the old intellectual, but to the young Marek Szczuka, uttering only a few lines in the film – simple yet sharp as a razor:

UB Officer: How old are you?

Marek Szczuka: A hundred.

UB Officer (hits him in the face): How old are you?!

Marek Szczuka: A hundred and one.

[…]

UB Officer: What were you doing during the uprising?

Marek Szczuka: Shooting at Germans.

Officer: And now at Poles?

Marek Szczuka: And you at sparrows.

DANCE OF DEATH – the polonaise and the “dumpster of history.” The polonaise scene in the literary prototype was a scene for which Andrzej Wajda wanted to make his film. It was supposed to be a spectacular culmination reminiscent of The Wedding by Stanisław Wyspiański, even though in Jerzy Andrzejewski’s novel, it held a rather modest place. Originally, the main emphasis was to be on the symbolic procession of Kotowicz the MC, but ultimately, a synthesis was chosen – scenes of the polonaise and Maciek’s tragic death interweaving in parallel editing (the displacement of these accents further highlights the fact that the last shot belongs to Chełmicki). This technique allowed the creators to generate meanings completely different from those that would have arisen in a polonaise sequence without the agony of the main character. Instead of diagnosing post-war Poland, represented by a procession of traitors and careerists, Wajda focuses on the drama of a lost generation, represented by Maciek Chełmicki.

Andrzej Wajda concluded his trilogy with Ashes and Diamonds, which he opened four years earlier with A Generation (a film considered the swan song of the Polish Film School) and continued with the acclaimed Kanal. As the author of the war triptych, he was hailed as the bard of the Home Army generation and in the future as the leader of the most important formation in the history of Polish cinema. In the context of Ashes and Diamonds, Aleksander Jackiewicz spoke prophetically about Wajda:

It rarely happens – not only in film art – that a young artist, like Andrzej Wajda, from the very beginning of his career, almost from its threshold, embarks on a work that may be the greatest work of his life.

Another Wajda worked on the set of Ashes and Diamonds – Leszek, the younger brother of the director by four years. Leszek Wajda was a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow and collaborated with his brother on the production of Innocent Sorcerers and Samson. He also served as a set designer on the set of Janusz Morgenstern’s film Premiere Tomorrow.

GOLDEN DUCK of the magazine Film, which represents the voice of the ordinary viewer. The Golden Duck was awarded to Wajda’s film in January 1959 (it’s worth noting that the previous year Kanal was victorious). The results of the third plebiscite of the magazine were as follows: out of 21,260 votes sent to the editorial office, as many as 12,040 (almost 57% of the voters) belonged to fans of Ashes and Diamonds. Second place was taken by Farewells by Wojciech Jerzy Has (2,570 votes), and third place by Ewa Wants to Sleep directed by Tadeusz Chmielewski (2,022 votes). In fourth place was Andrzej Munk’s Eroica (with 1,511 votes).

Words by Milosz Drewniak