SPACE MUTINY: Science Fiction as the Unknown Sister of Battlestar Galactica

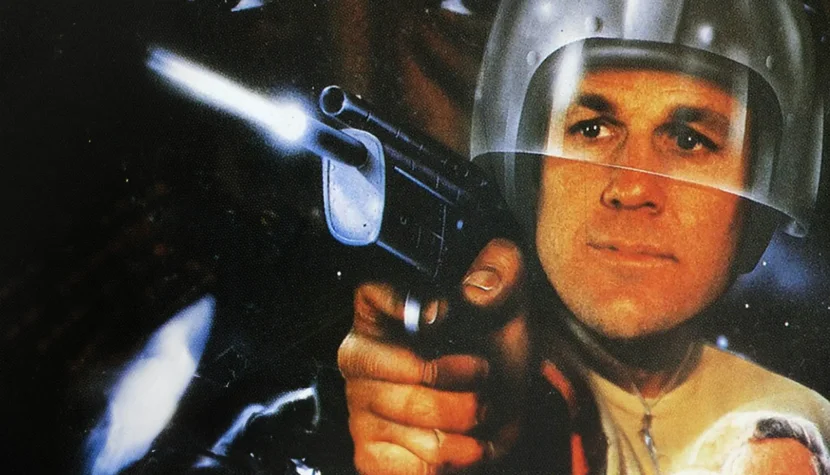

“Space Mutiny” by David Winters and Neal Sundstrom is a feature-length production aimed primarily at fans of Babylon 5 and Battlestar Galactica. Aesthetically, however, it bears the hallmark of cheaper 1980s science fiction films. Produced by the relatively obscure Action International Pictures (AIP), founded by Winters and David A. Prior—known for the cult classic action film Deadly Prey—Space Mutiny never achieved such cult status but draws heavily on Battlestar Galactica, which is sure to excite fans with its engrossing execution. The lead role is played by Reb Brown, who some might recall as Captain America in two late-1970s Universal TV productions. Revisiting those can show how Steve Rogers’ character has evolved over nearly 50 years of cinematic history.

For sharp-eyed viewers, Reb Brown’s performance in Space Mutiny mirrors his style from Captain America. This is all the production needs, given its straightforward plot and clear-cut characters. Fans of cult science fiction will quickly notice something else: the special effects, spaceship models, laser shots, weapons, and more closely resemble Battlestar Galactica. In fact, they are the same. How did this happen?

The story is simple. Somewhere in space, a massive mother ship—or colonization station, akin to a temporary artificial planet—drifts along. Generations are born and die aboard, never experiencing the sensation of walking on real earth under natural gravity. In a way, humanity loses its identity, becoming a species condemned to eternal wandering—a cosmic homeless existence. Naturally, one generation eventually rebels, yearning to settle somewhere. Thus, the intergenerational ship Southern Sun becomes a prison, with rebellion as the only means of escape. However, the rebellion’s leader, Kalgon, is not motivated by noble desperation. Instead, he seeks to settle in a pirate-occupied planetary system for his own convenience, intending to become a dictator on one of the planets. The ship’s people wouldn’t gain the freedom they desire but merely a new prison. Standing in his way is pilot Dave Ryder, who believes he can protect the exiled population singlehandedly. The entire action hinges on this heroism.

And there’s plenty of action. The generational ship comes under attack from small, agile pirate ships. Viewers will witness battles within the enormous residential complex of the ship, including sequences with electric mini-car chases. Expect magical rituals, wildly colorful costumes, and even a love scene, albeit not fully undressed. The hero dispatches enemies in a white tank top that somehow remains pristine through most of the combat. Laser shots create clouds of smoke, and collapsing silver-painted beams are likely made of balsa, Styrofoam, or plastic. There’s even a cheeky gesture, and in the finale, the main antagonist gives a piercing glare, suggesting the story isn’t over yet. Love and freedom ultimately triumph. The pirates are defeated, and the hero’s victory is more emotional than political, as he even finds love. What more could one want from a science fiction movie with no aspirations of becoming a box-office juggernaut?

Perhaps the intent was to evoke Battlestar Galactica nostalgia and remind audiences of the series’ cultural impact by the late 1980s. For me, it succeeded. This kind of fan service is classy. However, what worked at the end of the ’80s doesn’t look as good today. The film is available online in its original version, and the dialogue poses no challenges, as most of the action revolves around gunfights, chases, and so on. It doesn’t matter if laser shots miss their targets or the hero’s punches don’t land convincingly. That’s not what these films are about. It’s about the atmosphere—the fantastical quality of 1980s sci-fi. The viewer is meant to be swept away by this world, without questioning what’s scientifically plausible or fantastical. In films like this, space is loud, massive ships traverse its depths with little regard for engineering feasibility, and heroes observe distant planets on screens resembling old CRT monitors—not even the flat ones.

You’ll find all this in Space Mutiny. Every element has its place. It doesn’t deviate from the formula even slightly, yet it’s still entertaining. It reminds us that the love of science fiction is, above all, a love of imagination, not science.