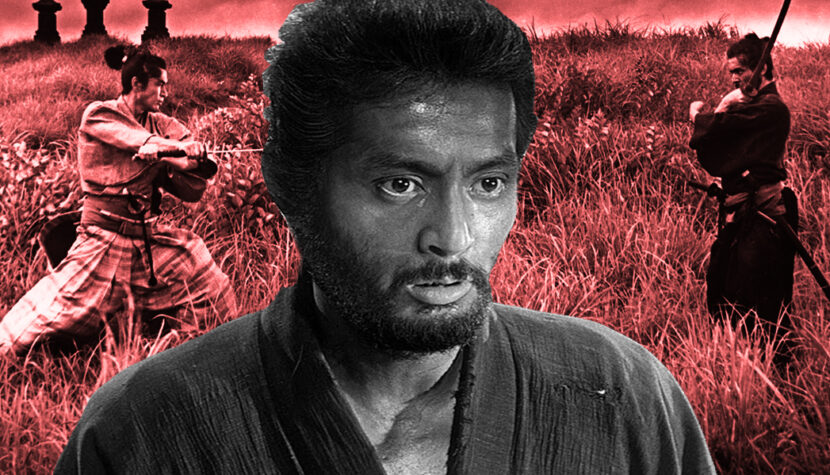

HARAKIRI and SAMURAI REBELLION. Masaki Kobayashi’s Masterful Jidaigeki

Many films have been lost, and even more are in very poor technical condition. Additionally, the filmographies of directors, screenwriters, actors, and cinematographers are vast, often comprising dozens of titles.

Akira Kurosawa directed 35 films, Yasujiro Ozu 55, and 45 films were based on Kogo Noda’s scripts. The bodies of work of other film crew members (cinematographers, editors, production designers) are even more extensive. Since the end of World War I, the Japanese film industry has developed extremely dynamically, with producers eagerly investing money in cinema. In such circumstances, it is difficult to choose a single path for selecting, analyzing, and interpreting titles to exhaust the topic. Samurai

Therefore, it is worth focusing on a small but cohesive fraction of this extraordinary filmography. One could present a phenomenon that can be encapsulated within a few films, characterizing and evaluating it in a thorough and complete manner. Such conditions are ideally met by the works resulting from the collaboration of two filmmakers: director Masaki Kobayashi and screenwriter Shinobu Hashimoto. Together, they made only two films: Harakiri (1962) and Samurai Rebellion (1967). These films are very similar, addressing similar issues and, at times, corresponding with each other. Both films feature similar motifs and situations (a child as a symbol of hope, an individual dominated/imprisoned by law, and rebellion against rigid, non-functional rules). The characters face similar ethical and moral dilemmas.

Auteur cinema is typically recognized by its directors, especially when they also write the screenplays for their films. Screenwriters usually play a secondary role. This is not exclusive to auteur cinema. The same applies to major American blockbusters. The screenplay is an absolutely fundamental component of a film: it creates the psychological portraits of characters, guides us through conflicts, and dictates the sequence of events. The primary substantive content of a film lies in the screenplay, which cannot be overshadowed even by the worst direction.

I would like to draw attention to everything that stems from the very properties of the screenplay, stripped of directorial vision and staging. To strip Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion of their visual side and focus solely on the words. In both films, dialogue plays a very important role, and the non-linearity of the action surprisingly changes the viewer’s perspective, ultimately leading to a change in the assessment of the characters and events presented. Therefore, Shinobu Hashimoto will be one of the main protagonists of this analysis. However, it is impossible to ignore the stunning directorial ingenuity of Kobayashi, so I will also dedicate some space to it.

I must clarify in advance that Samurai Rebellion is by no means a derivative film compared to the five year older Harakiri. They are only based on a similar plot scheme. The conflict is played out between the same parties. One side is represented by the clan, and the other by the individual/family. The mutually exclusive priorities result in conflicts that can only be resolved through bloodshed.

Jidaigeki

Japanese cinema, like American cinema, has its genres and conventions. They are realized, understood, and named differently. In this text, I will focus on historical-costume cinema, defined as Jidaigeki. These are films depicting medieval Japan, with samurai as protagonists. If Jidaigeki were to be compared to any Western film genre, it would probably be the costume drama or swashbuckler film. Its heroes are knights – individualists known for their honor and skill with weapons. In Japan, the most famous director of this genre is certainly Akira Kurosawa. He created a paradigmatic style, and his films became the standard for evaluating other representatives of this genre. At the same time as him, Masaki Kobayashi created his two films.

The most famous films of Akira Kurosawa – Seven Samurai, Red Beard, The Hidden Fortress, or Yojimbo – have an apologetic character. They present samurai and the samurai code (bushido) as bastions of higher values. They restore order when it is disrupted. They stand guard over safety and resist threats and injustice. For Kurosawa, the samurai and his principles often serve as benchmarks that people should strive towards and uphold. The heroes of these films are morally steadfast, profoundly wise, and exhibit extraordinary intuition in judging people and phenomena. Samurai are presented as heroes who restore balance to a disturbed order.

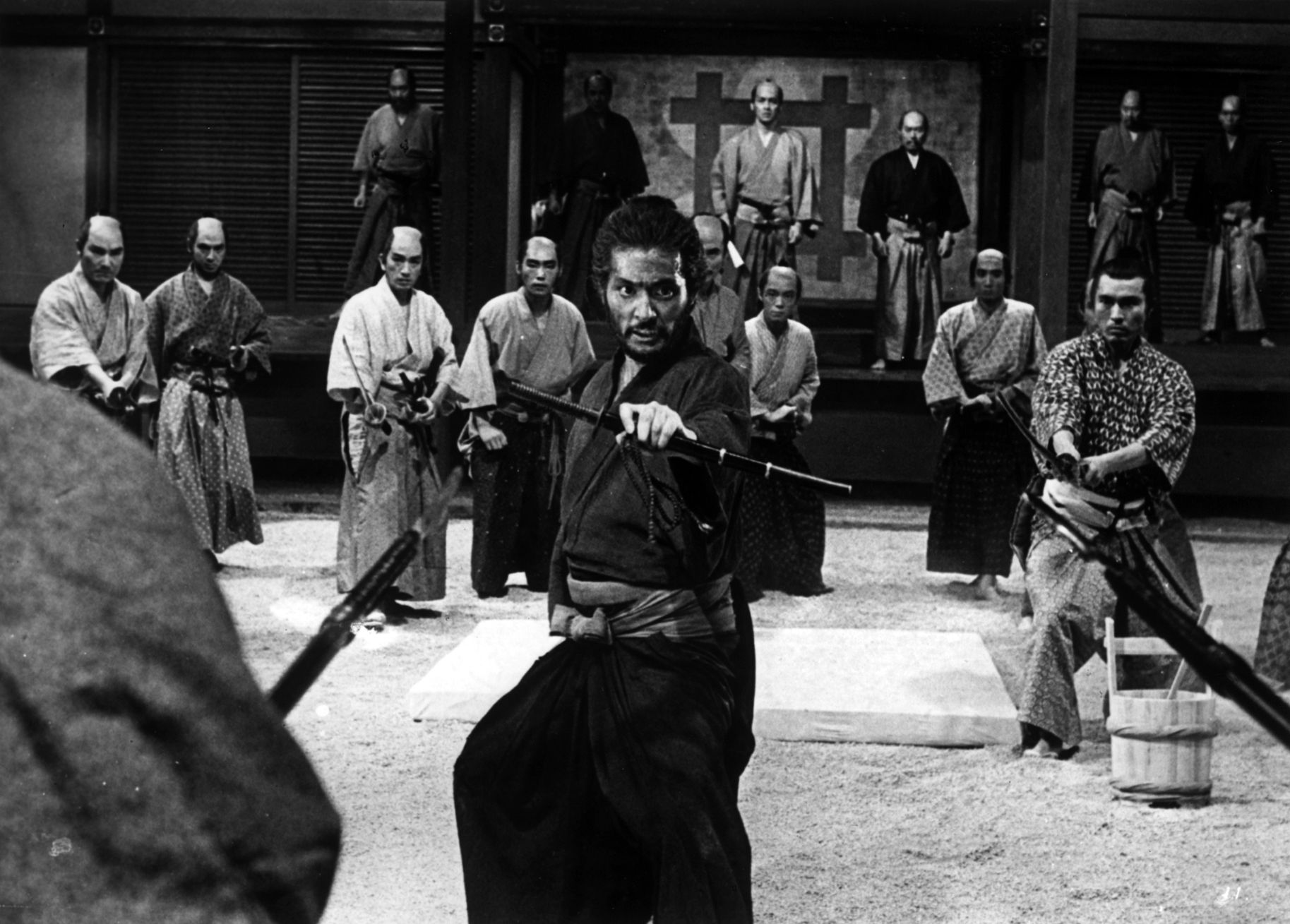

Kobayashi’s films, in contrast to Kurosawa’s works, are much more critical and reflective. Bushido is shown as a prison for human sensitivity. The characters in Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion either escape from it or fight against it. They realize that the code blinds them and deprives them of the opportunity to properly assess situations. A symbolic scene illustrating this approach is from Harakiri, where Hanshiro breaks into the palace and topples the idol representing samurai strength and associated values. It is destroyed by the main character. Kobayashi’s films are quite radical in their message. They challenge the stereotypical image of the samurai, inviting viewers to engage in discussion and encouraging a critical view of the world of Japanese warriors.

Samurai Honor as a Facade

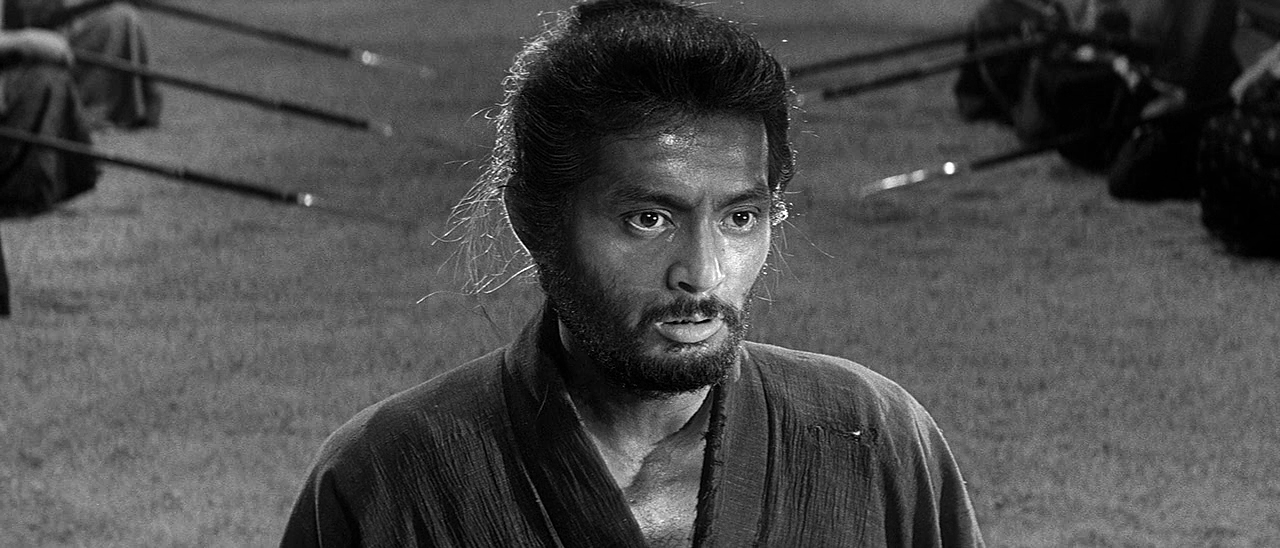

Both films can be seen as two variations on the essence of honor. The main character of Harakiri – Hanshiro Tsugumo (played by Tatsuya Nakadai) – becomes a prisoner of ethos. The primary function of the samurai sword is not to kill but to symbolize dignity, courage, bravery, wisdom, and social status. In Harakiri, Kobayashi and Hashimoto subversively attribute to it qualities such as pride, blindness, and vanity. All the traits originally associated with the samurai sword are compromised.

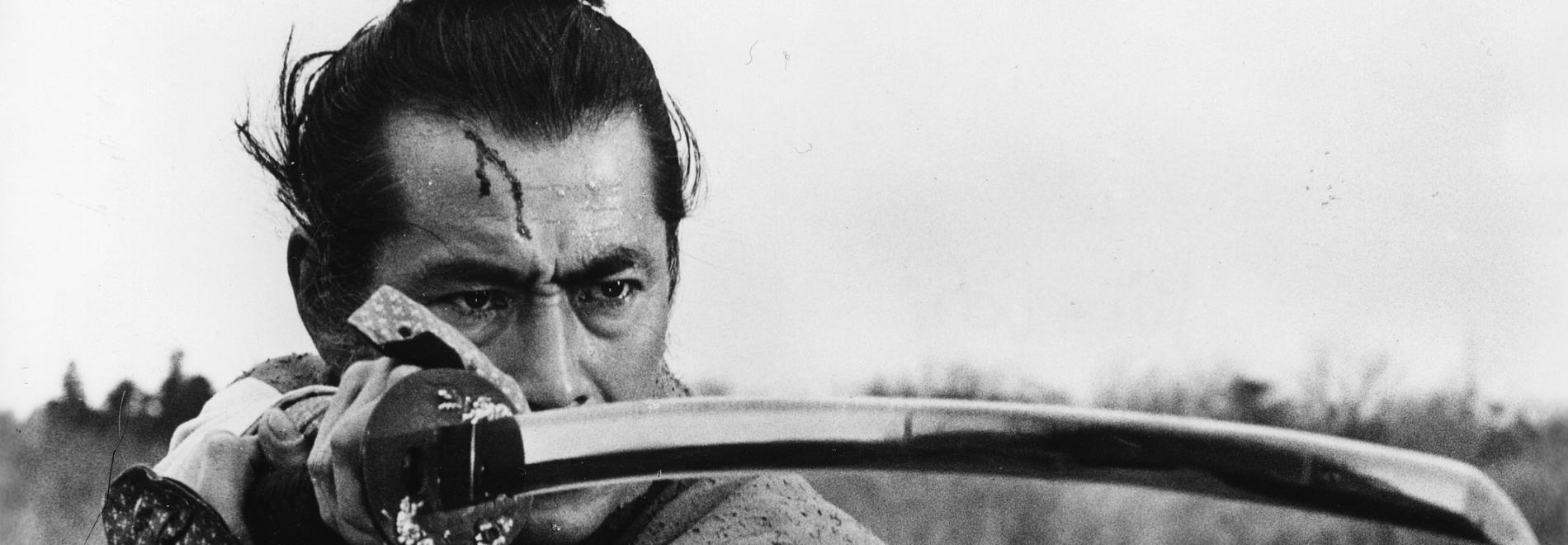

Hanshiro comes to this realization and turns his sword against the clan responsible for his son-in-law’s death, who uphold the code’s principles. He feels exploited by the clan leaders’ ruthlessness. Isaburo (played by Toshiro Mifune) in Samurai Rebellion opposes an institution guided by illogical and incomprehensible directives, completely disregarding the individual. The rules are not made for people; rather, people are meant to follow them unquestioningly. Kobayashi in Samurai Rebellion critiques the then-social system, continually siding with the besieged, threatened family. Common sense is a rebellion against unjust, ruthless laws.

At the end of Harakiri, Saito Kageyu, outraged by Hanshiro’s speech, repeats: Samurai honor is a facade?! The actor’s performance (Rentaro Mikuni) suggests that the clan leader is convinced by Hanshiro’s story. However, he is too institutionalized to imagine contradicting and defying tradition, thus he is forced to lie to himself in the end. He does this to protect the clan’s position and maintain the status quo. Yet, he surely feels the ground slipping from under him. The confrontation with Tsugumo is the beginning of a powerful avalanche that will strike the samurai ego. The manager can be called a tragic hero. He faces a conflict that cannot be resolved peacefully. He is a reflective and emotionally mature person, understanding Hanshiro’s determination. On the other hand, he still represents the code and the legal order, for which the value of an individual’s life is negligible. This also marks the difference between Samurai Rebellion and Harakiri. The former is filled with grandeur (patheticness), while the latter is a tragedy, a drama.

The complexity of Hashimoto’s screenplays manifests on two levels. First, the universality of the stories. Although both films take place in distant, bygone eras – the 17th and 18th centuries – and come from a clearly defined cultural context, they address universal issues. In the costume of samurai cinema lies a conflict understandable in any geographical context. This is not only a feature of these two films but also of his other works. Hashimoto frequently collaborated with Akira Kurosawa, who garnered acclaim from audiences worldwide. His screenplays underwent remakes and reinterpretations in the West. It’s worth mentioning The Hidden Fortress, which inspired George Lucas in creating Star Wars, and Seven Samurai, which was transposed to the Wild West, resulting in The Magnificent Seven directed by John Sturges. A similar convention was used in the animated film A Bug’s Life. This proves the resonance of this screenwriter’s texts, which do not require special decoding for European/American conditions. There are also reverse situations. Perhaps the most famous film by Kurosawa, Throne of Blood, is based on William Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

This leads to the conclusion that the often-used concept of cultural codes, employed as an explanation for the inability to communicate between different cultures, does not entirely hold true. Many existential, moral, or ethical issues have the same source and the same symptoms. The second level is purely formal – experimenting with the chronology of events. It causes surprising changes, builds complex character psychology, and forces the viewer to suddenly reassess the characters’ actions. In Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion, we have two exemplary cases of this technique – flashbacks at the very beginning of the films. They create a sense of kinship between the two texts, making it easier to associate them with the same author.

Flashback in Harakiri

Kobayashi and Hashimoto mislead the viewer at the beginning of Harakiri. The film starts with the arrival of a young ronin, Motome, at the residence of the clan leader. This is not the first time Kageyu has encountered such a case. Increasingly, samurai are losing their jobs and are forced to wander aimlessly. Honor dictates that they commit the titular harakiri, a suicide in accordance with the code. However, rulers, moved by the brave stance of the samurai, sometimes take them into their court or give them a modest advance and send them away.

It seems that Motome arrives with this purpose. The initial scenes involving him suggest that we should see him as a coward and a hypocrite, bringing disgrace to the samurai status. Moreover, it is discovered that Motome’s sword is made of bamboo. This further compromises him and reveals the insincerity of his intentions. For him, honor is a bargaining chip, not a value. His punishment, being forced to commit seppuku with a bamboo sword, is brutal but also justified. Kageyu’s outrage, as he adheres to the samurai code, can be defended. His decision is meant to serve as a warning to others. This is the tone in which Kageyu presents this story. He tells it to another samurai, arriving with the same intentions, Hanshiro, the main character of the film. Hanshiro gets into the court and hides his connections with Motome. The retrospective story told by Hanshiro, revealing his true intentions, completely changes the viewer’s assessment of all the characters. The audience is forced to look differently at the proud Hanshiro and the cowardly Motome. We come to understand the true motivations of the characters.

This screenplay technique questions apparent objectivity and attacks the ruthlessness and rashness of passing judgments. It is not merely for plot variety. Its main task is to build the psychological portrait of the characters. Harakiri is based on subjective, intentionally limited narration. The film is not told from the perspective of an omniscient, third-person narrator, which makes it strongly affect the viewer and cause a strong identification with the characters. The non-linear structure of Harakiri is not art for art’s sake, a play with film time; it is not the film’s theme – rather, it fulfills an important dramatic function, enhancing the conflicts.

Flashback in Samurai Rebellion

The main character of Samurai Rebellion is a distinguished samurai, Isoburo Sasahara (Toshiro Mifune), who holds an important position at the court. The film’s action takes place several decades later than the previously discussed Harakiri. The feudal system still operates in Japan. The political and social context is very similar. The conflict in Samurai Rebellion will be played out between the same parties. Isoburo’s son, Yogoro, is forced to marry Ichi, a girl banished from the court. The woman supposedly committed shameful acts: she insulted and attacked the clan leader. This behavior is unheard of and unacceptable for those times. However, Ichi must remain under the clan’s control, so Yogoro is chosen as her husband. Until this point, we imagine Ichi as a mentally unbalanced, aggressive person. Thus, Ichi is reluctantly accepted into the household by Isoburo and his son. They agree only to maintain their own position.

Over time, however, love develops between the newlyweds. This is caused by Ichi’s account of what actually happened at the court. The woman was used and compromised. She was only meant to bear a child for one of the ruler’s sons. She had no right to care for the newborn and was even banished from the court. After some time, Yogoro receives an order to send his wife back. This decision by the authorities causes a firm opposition in him, which is even more strongly manifested by Isoburo himself. The retrospection and frequent changes in points of view applied by Hashimoto create an “emotional roller coaster” for the viewer, who must constantly reinterpret their assessment. Following the characters, the viewer must continually fill in the gaps in the story. Just like in Harakiri, the non-linear narrative serves a dramatic function. This is certainly a hallmark of Hashimoto’s writing style. He is mainly interested in building complex psychological portraits of characters, rather than experimenting with storytelling time. The latter function is merely a tool to achieve the first assumption.

The Child

A characteristic feature of both films is the appearance of a child, an unaware, unshaped representative of the new generation. On this level, Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion correspond with each other. In Harakiri, the successive deaths of Motome, his wife, and later their child (Kingo) lead to an outburst of anger in Hanshiro. Throughout the film, the reality in which the characters live becomes increasingly grim. The birth of a child is one of the few happy moments. It unites the entire family. Kingo’s death has a symbolic dimension. Kobayashi sees no chance for improvement in the criticized feudal system. The rulers cannot change when the youngest generation dies. People are thus deprived of motivation to work, and they have no need to engage in anything. This leads Hanshiro to complete despair, on the brink of desperation.

In the 1967 film, the creators are more optimistic. They leave the viewer with hope for a brighter, better future. Samurai Rebellion also ends in a bloodbath. Both sides of the conflict suffer huge losses, but Isoburo’s grandson survives. He is taken under the care of an honest woman. The screenwriter and director have changed their attitude. This time, death was not ruthless; it left good, untainted people alive. Isoburo’s sacrifice, unlike Hanshiro’s, is not merely an act of revenge. The character played by Toshiro Mifune ultimately wins by saving the defenseless Tomi. The film leaves the viewer with the feeling that better times will come in a few years. Tomi is a symbolic light at the end of the tunnel. In this bitter, accusatory film, he is a breath of optimism and hope for a better tomorrow.

Related Works

My goal was to present Harakiri and Samurai Rebellion as films that often correspond with each other, addressing similar issues. The samurai myths, customs, and rituals are attacked in both. Both films have a similar critical character, attacking the feudal system and the institutions that maintain it. The characters have similar ethical and existential doubts. Additionally, the two films are connected by their screenplay structure. By using retrospection, which completely changes the viewer’s assessment of the characters’ actions. This narrative technique clearly links Harakiri with Samurai Rebellion. Aesthetically, Kobayashi’s films are also similar. Very meticulously arranged set design and space, precise, almost calculated frames. The lack of any randomness or improvisation indicates that the same creator is behind both films. Each shot is deeply studied, thought out, and almost mathematically measured. Kobayashi and Hashimoto’s films are thus consistent not only ideologically but also aesthetically and technically. Individually, they engage in a dialogue with the viewer in a very effective and substantively bold manner. Together, they become an even greater challenge.