PSYCHO: Hitchcock’s Masterpiece of a Thriller Explained

What they find there will haunt their dreams for the rest of their lives.

Just fifty-six kilometers away in Weyauwega, writer Robert Bloch lives and works. He had long since shaken off the influence of his mentor, H.P. Lovecraft. He has just begun working on a book that would bring him incredible fame – Psycho. Perhaps he skimmed a newspaper article about Gein’s arrest. After all, it was quite a local sensation. But before all the details came to light, Bloch had almost finished his work, fascinated by the idea of how skillfully evil can hide beneath a mask of normality. He didn’t realize that the truth had already outpaced fiction. With just a few final chapters left, some editing, and the crafting of an ending, Bloch receives help from the Gein case, which is revived in the newspapers. Bloch is shocked. Norman Bates, his character, is not Gein, but how many similarities there are! Could he have invented and described something that was happening almost right next door? Did he sense something? Did he observe something? Bloch makes final revisions and includes a reference to Gein in the story. He will return to him in another draft years later. Psycho is ready for publication. The machine is in motion.

Alfred Hitchcock’s assistant, Peggy Robertson, is browsing newspapers. She comes across an enthusiastic review of Psycho by Anthony Boucher. She feels a surge of excitement. She buys the book and takes it to her legendary boss. Hitchcock immediately sees he has struck gold. He buys the film rights for $9,500 and is even willing to finance the film himself. He battles the reluctance of Paramount Pictures but gets his way.

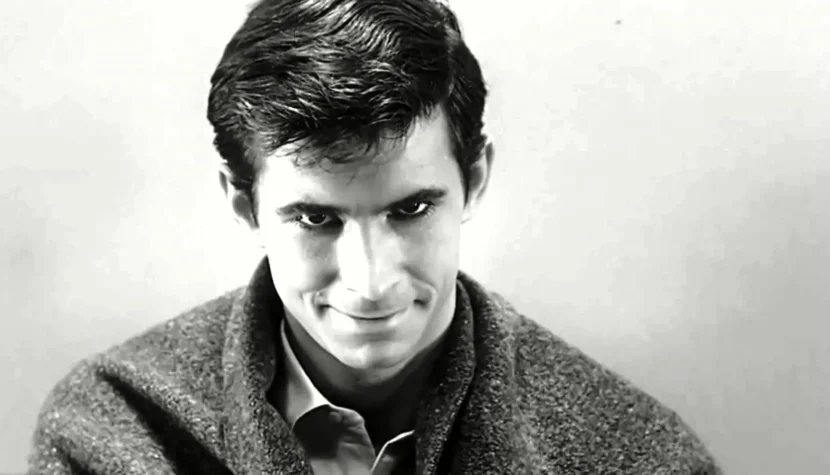

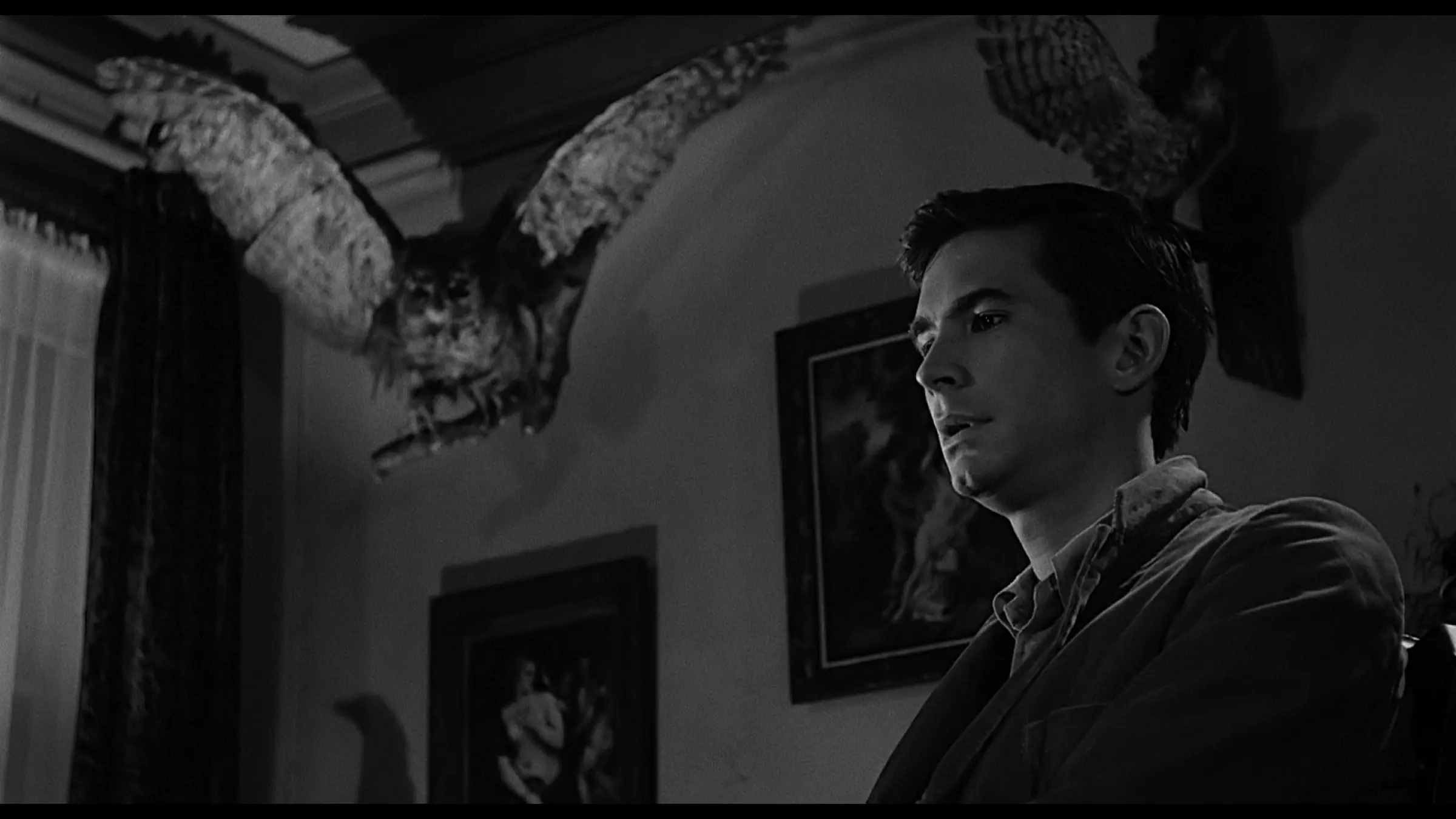

An experienced television writer, veteran Alfred Hitchcock presents, James P. Cavanagh, starts work. But something is wrong. The rookie assistant, Joseph Stefano, sees it clearly. This is his breakthrough moment; he musters the courage to arrange a meeting with Hitch. He has a few ideas. To Stefano’s astonishment, Hitchcock finds them good enough to hire the ambitious assistant to work on Psycho. Above all, the overweight, repellent middle-aged alcoholic fascinated by the occult and pornography is transformed into an attractive young man. Anthony Perkins, says Hitchcock. Anthony Perkins it will be.

Thus, Norman Bates was born.

Ed Gein. Truth Outpaces Fiction

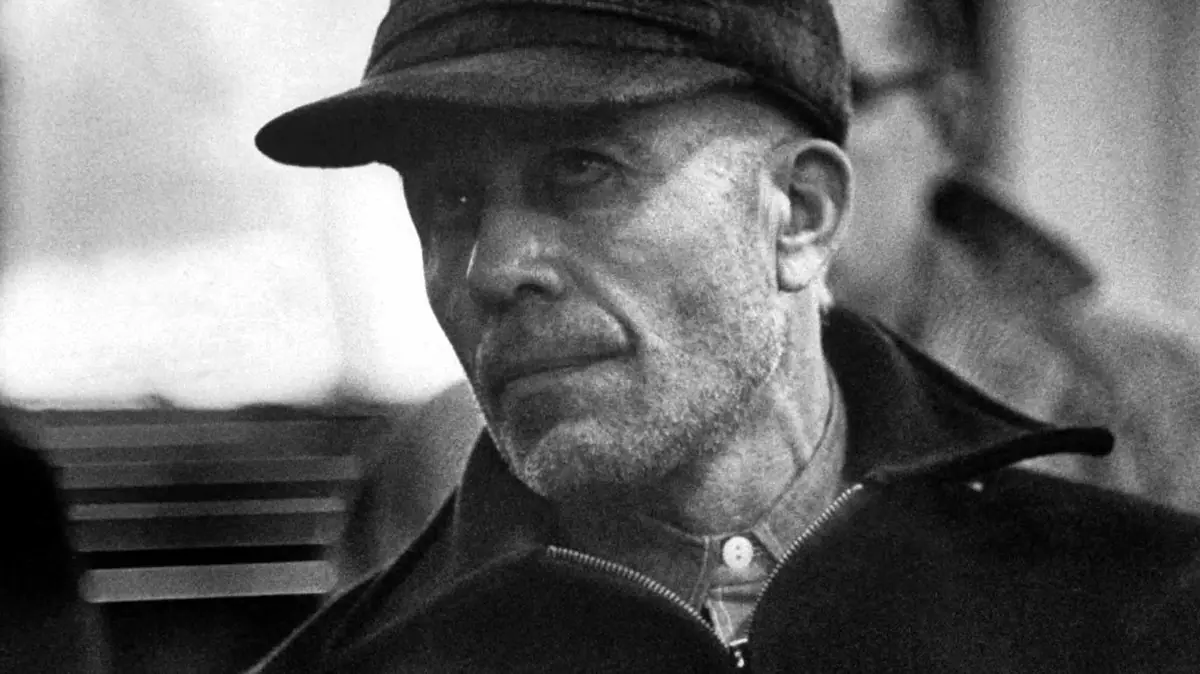

Tight jaws, narrow lips, several days’ stubble. The look of a cornered animal, a cap pulled deep over his forehead. He looks scruffy, perhaps not very pleasant, but certainly not insane. Just an ordinary worker, maybe a farmer? Nothing special. Someone you wouldn’t give a second thought to.

Edward Gein did not have the easiest life. Born in Wisconsin as the younger of two sons of an ill-matched pair, George and Augusta, George spent most of his life trying to remain invisible. The household was run with an iron fist by Augusta. She did not hide her deep contempt for her husband and men in general – weak, sinful, tainted by disgusting carnal desires. But God wished to test her, blessing her with two sons. Augusta accepted this cross with the humility of a fervent Lutheran. Her task was to make Henry and Ed understand the concept of sin and learn to defend themselves against it despite their flawed and submissive male nature. She set about her task systematically. No friends, leaving the house only for school and church. Every afternoon spent studying the most frightening parts of the Bible. Constant sermons about morality, or rather, the amorality of everything around: women, alcohol, novels. Every woman, Augusta preached, failing to notice the logical inconsistency of her statements, was a source of corruption, a whore, and a tool of Satan. From time to time, she also administered solid beatings to her sons for the good of body and spirit.

Henry rebelled and resisted, cursing and raging. Edward did not. Mocked by schoolmates, ridiculed by teachers for his nervous tics and uncontrolled laughter, he tried to hide in his own world. He read a lot and had a rich imagination. Gradually, Augusta became the center of his universe, literally the woman of his life, his only friend. He loved her, worshipped her, feared her – this tower of wisdom, this rider of the apocalypse, and angel of doom with a flaming sword. Yet he hated her and felt revulsion toward her with equal force. He went out of his way to gain her approval – generally without success – and at the same time could not overcome his disgust for the vision of the woman she embodied, neglected, ugly, dirty. He was fascinated by his peers, spying on them and then sinking into self-contempt. Neighbors often hired him to look after babies. He was great at it. He got along with children, was not afraid of them, and they accepted him. Where adults were concerned, there were laughter and eternal fear.

When he grew up, he discovered that the same comfort and liberation from fear were provided by the dead.

After the natural death of George and the otherwise suspicious death of Henry in a fire, Edward and Augusta were left alone, becoming even more dependent on each other. In 1945, after a series of strokes, she also passed away. Ed had no kind soul in the world. Lost, terrified, and lonely, he desperately sought a reason to keep living. He became obsessed with reading obituaries and digging up fresh graves, bringing home body parts, most often of middle-aged women resembling his mother. With mad precision, he turned them into everyday objects – lamps, bowls, chair coverings, straps. Would mother understand? What would she say? Who should he become to finally please her? Eventually, he understood. He had to become her.

The police caught onto Gein in 1957, while searching for the missing Bernice Worden, a local shopkeeper. Her headless, skinned body was found in a shed, suspended by chains from her ankles. Gein had shot her, just as he had Mary Hogan three years earlier. Both were to serve as the basis for his dream – to sew a suit from human skin, allowing him to finally transform into a woman. To become Augusta.

Since Gein could not be proven to have committed more murders (although he was suspected of them), he does not meet the classic, albeit increasingly challenged, definition of a serial killer. He was tried for the murder of Bernice Worden, declared insane, and committed to a mental hospital for life. He died in 1984. It is said that he remained an ideal, trouble-free inmate until the end. His record included “schizophrenia,” “deep psychosis,” “transvestism,” and “necrophilia,” but throughout his incarceration, he never needed so much as a sedative injection. Perhaps because he finally felt happy.

Sheriff Art Schley, who led the investigation, never recovered from the trauma of the memory of nine masks of women’s faces staring at him from the wall in the home of this quiet Ed Gein, so perfectly ordinary that no one paid him more than one thought.

Norman Bates. The Cinematic Brother of Ed Gein

The story of Ed Gein has influenced, continues to influence, and will likely continue to influence popular culture. Twisted by his mother, crushed by the circumstances in which he lived, likely also poorly treated by genetics and nature, the “ghoul from Wisconsin” became a sort of icon due to the macabre and repulsive – and thus media-attractive and catchy – elements of his biography. Buffalo Bill. Leatherface. Bloody Face. Deranged, In the Light of the Moon, House of 1000 Corpses. Comics and songs, black humor and satire. The tragedy of Gein’s victims and, yes, also the tragedy of Gein himself, filtered through a spin and presented in the form of horror and absurdity. It is sad, but in no way surprising – the taming of such macabre, such improbably twisted meanders of the human mind, is a completely natural attempt to maintain balance and a sense of safety.

Of all the cinematic characters inspired by Gein, Norman Bates is the most credible, and his story is a refined blend of horror and psychological dissection. Bates is not simply terrifying; his role is not just to scare, and he lacks the comic-book villainy. He is very human, evoking sympathy.

Sympathy, indeed, is a difficult and complex issue. Should one feel sympathy for Gein? For such a monster? For such a human horror? Perhaps rather for Mary Hogan and Bernice Worden, their families, and the loved ones of other missing persons whom he was suspected of killing and who did not receive any justice. However, I think that the ability to empathize is precisely the strongest, most solid barrier behind which consciousness can hide when our safety is once again shaken by another manifestation of human depravity. There seem to be more and more of them, and we hear more and more about them. Disgust and aversion are simply reactions of a healthy mind. Sympathy is an attempt to emotionally tame the darkness that can befall us all in one way or another.

Fascination with Gein can indeed be disturbing, but sympathy? Does it automatically lessen the gravity of his actions? Does it deny the need for justice? Does it insult his victims? So, what’s better? To turn the macabre into a caricature, filter violence through pop culture, or delve into its causes before we overlook the ticking time bomb right under our noses?

I had a very happy childhood

Just a side note since we are not dealing with Gein but with Bates, and they are by no means the same person, even if the inspirations (possibly stronger in the film than in the book) are apparent at first glance. Most importantly, Gein’s macabre craft didn’t reflect in the character of Bates; there is no grave robbing, no production of terrifying objects, nor the chilling idea of a costume made of human skin. What was physical for Gein remains in the psychological realm for Bates; what was a dream realized through experimentation with corpses for Gein is a fulfilled desire for Bates. Gein wants to be his mother. Bates becomes her.

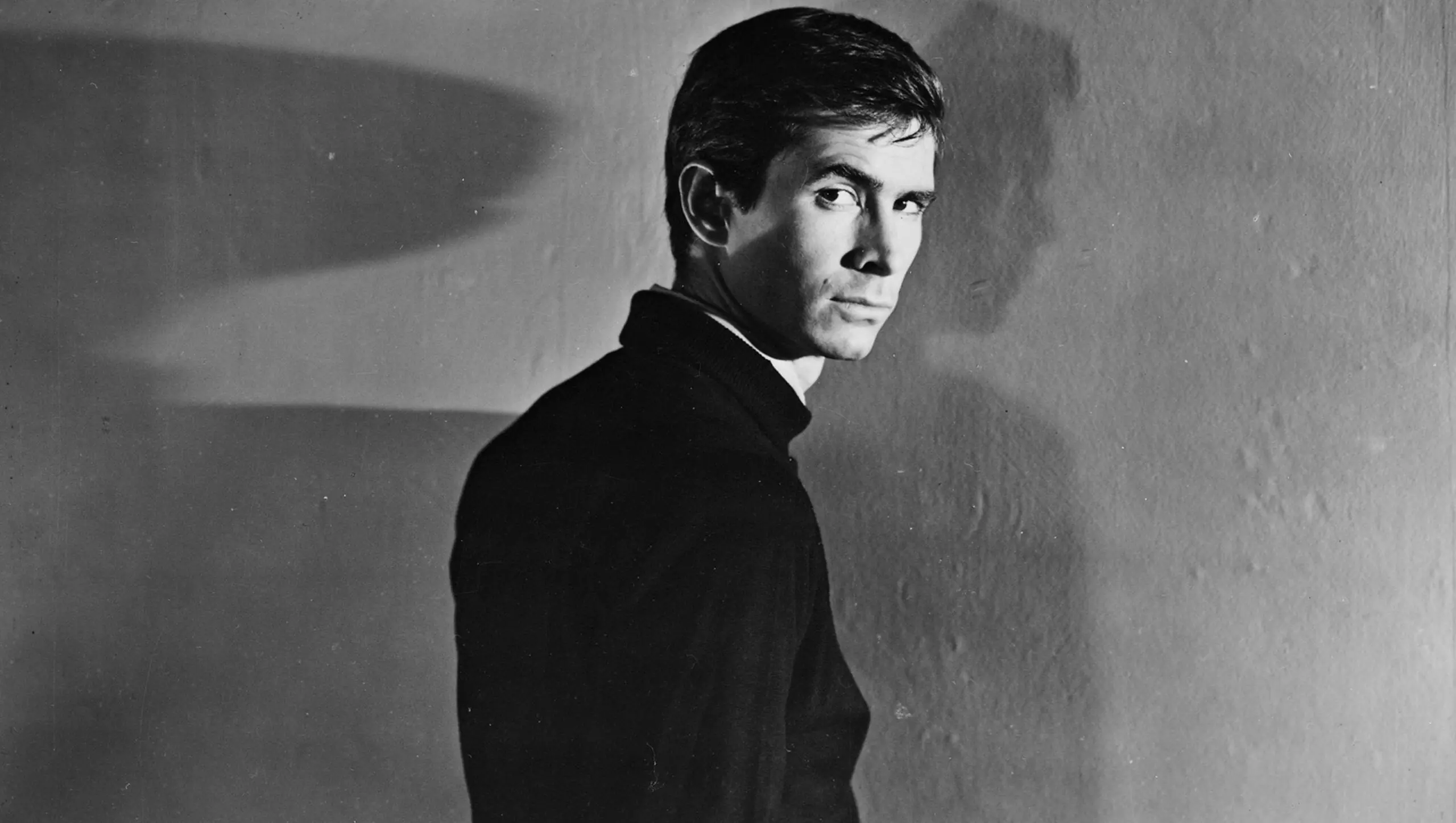

On this first, most easily observable level, Norman seems like a completely balanced person. Young, well-groomed, slightly smiling, a little clumsy, shy. Buried in isolation, sentenced to exhausting care for his sick mother. From Marion’s point of view (and at this stage, the viewer’s as well), the lawman hidden behind dark glasses, who earlier frightened her while she was napping in her car, seemed much more threatening. In fact, thanks to Norman, Marion, fleeing from justice, can finally relax. He doesn’t know her past, doesn’t threaten her in any way. To some extent, he understands her feeling of entrapment, the sensation of being caught in a trap.

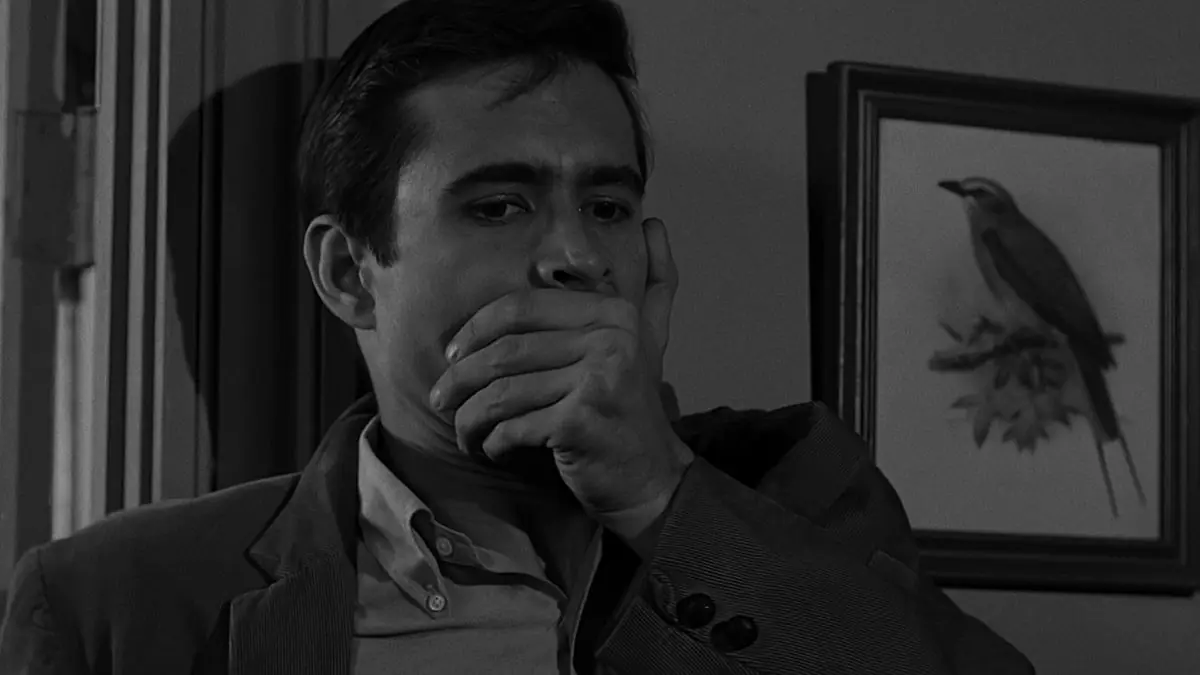

The brilliant dinner scene deftly outlines the relationship between Marion and Norman and the foundations of Norman’s character. There is erotic tension, a touch of innocent flirtation. There is an immediate connection with someone unfamiliar yet attractive. There’s also Marion’s protective concern for Norman’s future, for his feelings about having to care for his mother – She seems to hurt you, says the girl. And of course, Norman’s defensive speech: his mother needs him. She is a victim of life’s tragedy. She raised him alone. She is not a maniac; she’s not dangerous. Sometimes she just… loses control.

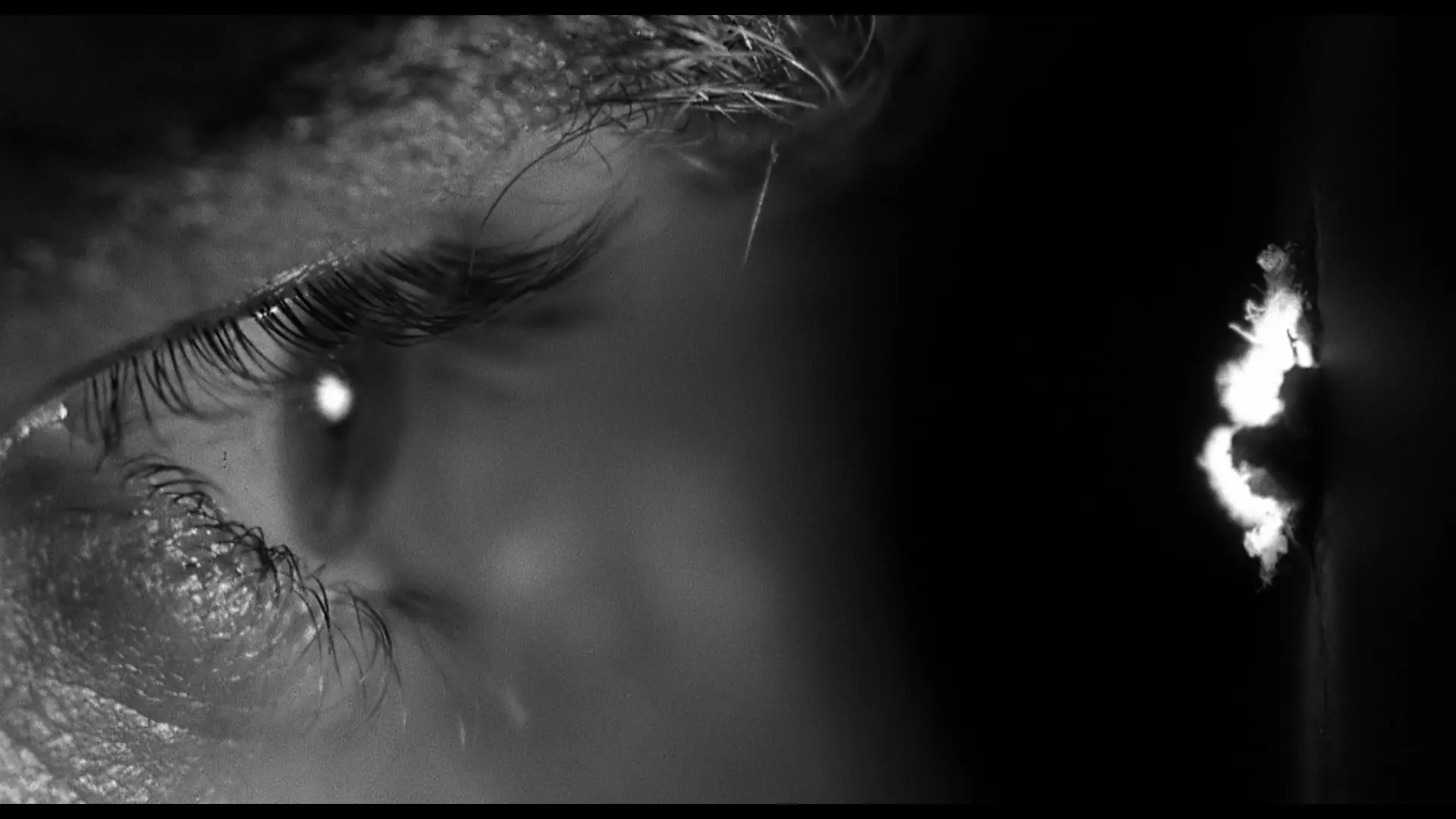

Marion sees an unhappy young man with doe-like eyes.

Norman sees an alluring and sexually attractive woman.

Mother sees reasons for screaming and jealousy – some stranger in her house?!

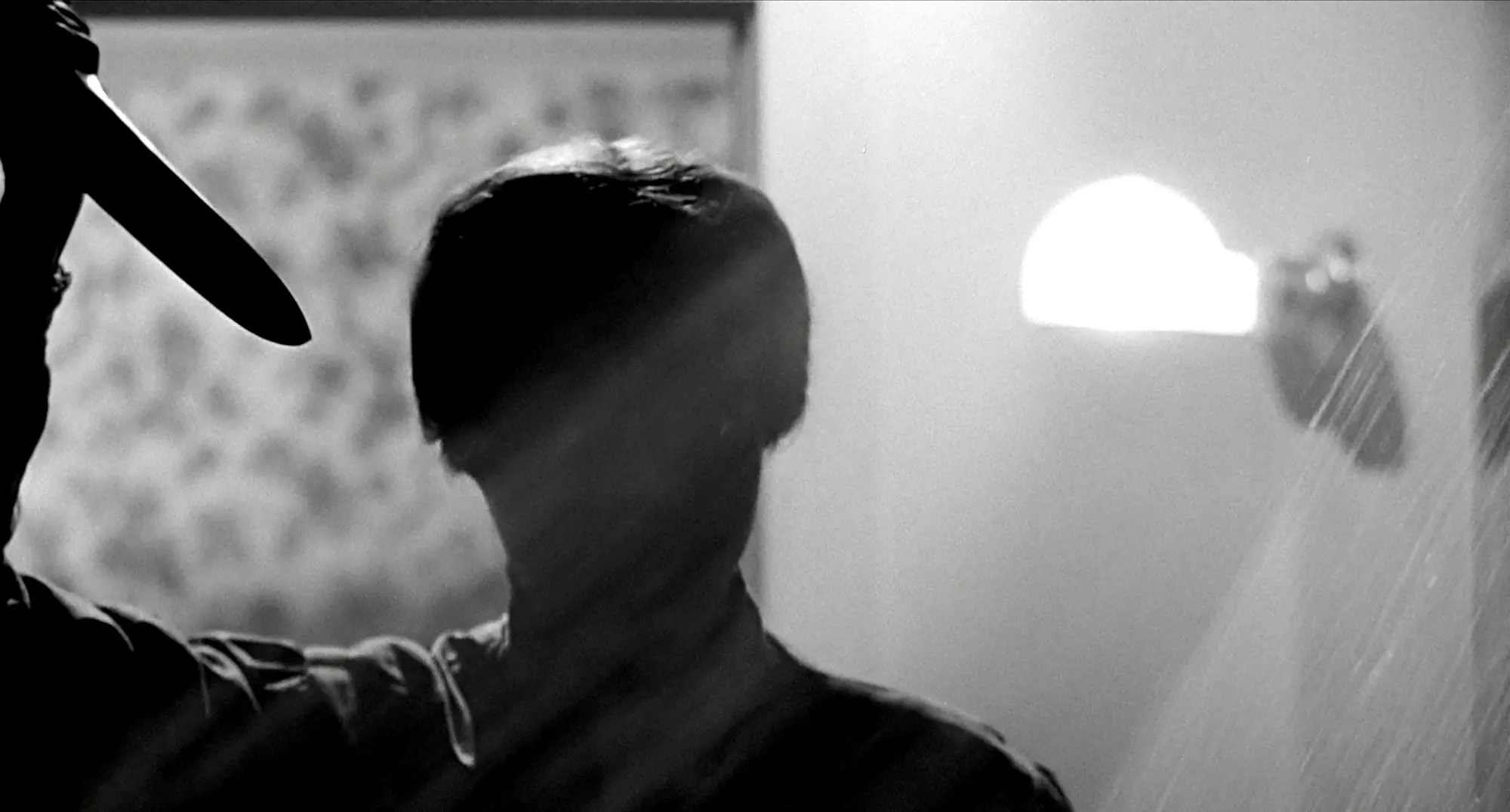

We see a mystery. A female silhouette with a knife. Marion’s dramatic death in the shower. And Norman, who begins the evening with nervous peeping through a hole in the wall and a tormenting sense of shame and crossing the boundaries of decency, ends by removing traces of the murder committed by this supposedly stable and harmless parent. Poor boy. But is he hard to understand? He won’t take his sick mother to court. He owes her the loyalty of a loving son.

Soon, however, we will learn that it’s not loyalty that drives Norman but jealousy, addiction, and guilt. Jealousy that led him to kill – ten years earlier – his mother and her lover. Guilt that turned into a fully functional second personality – Mother. And addiction, for which he created a shrine of memory for the deceased Norma, with her exhumed body at the center.

Did he try to regain balance? He probably tried. You locked me in the basement once before, Mother complains during one of the irrational quarrels between the two personalities. He tried to push her into the subconscious – the “basement” of his mind, but he couldn’t. Whenever he attempted to establish a normal relationship of a healthy man with an attractive woman, the Mother’s personality took control to brutally eliminate the rival. The circumstances also aren’t too favorable – in town, everyone knows him, and he knows everyone, and due to the newly opened bypass, guests almost never visit the hotel. Loneliness surrounds Norman and strengthens Norma. Probably a similar mechanism was triggered even during her lifetime.

This house is my whole world, says Norman, irritated, during a conversation with Sam. I had a very happy childhood. Mother and I were the happiest in the world. His evident nervousness and defensive stance during the aggressive questioning by the dominant man prove that the facade is beginning to crumble. Norman balances on the brink of understanding that his illusion is just that – an illusion. His mother’s actual death is both present and absent in his memory. The fear of the weak Norman makes him retreat entirely into his mind, allowing the strong Mother, capable of defending them both, to come to the fore. The stress of this confrontation is so powerful that Norman disappears completely, probably, as the specialist states in his speech at the end of the film – forever, safely hidden beneath the surface and perhaps, paradoxically, finally free… much like how Gein felt happy in the seclusion of the psychiatric institution.

So – why all this? What pushed Norman into the depths of the titular psycho?

From Norman’s account, we know that his mother became a widow when he was five, thus in the early phase of psychosexual development when, according to Freud, the Oedipus complex arises – the desire for a relationship with the opposite-sex parent and simultaneous rivalry with the same-sex parent. The problem is that Norman’s natural development was probably halted and suppressed by his mother’s dominant attitude. Her character appears to us in glimpses during “Norman” and “Mother’s” conversations and in remarks from outsiders. She seems to be a tough, relentless, demanding, and oppressive person. She speaks to her son with contempt, with reluctance, plays on his guilt, shames him, and humiliates him.

It’s easy to assume that the isolated location, Norma’s character, and probably her carefully suppressed Jocasta complex (stemming from a desire for control over her son, not desire) turned Norman into a complete recluse. Unable to express his sexuality through trial and error in normal interactions with the opposite sex, Norman locked himself into a flawed, Oedipal structure centered on and driven primarily by his mother. As with Gein, she became the woman of his life, though in Bates’ case, the sexual aspect is much more apparent, the theme of a relationship between two people of the opposite sex, incidentally related (whether consummated or not – probably not). Gein envies his mother for who she is – Bates envies the person who is with her. Furthermore, over the years, he develops the natural belief that she must also be jealous of him.

The saddest part is this additional aspect of Norman’s evolution after his mother’s death – judging from his statements, especially during the famous dinner scene with Marion, there is more self-confidence in him because he feels that now he is the one caring for someone weaker, defenseless, and dependent on him. This absurd paradox further enhances the tragedy of the whole situation because increased self-confidence made him reach out to people more often, specifically – to women. Thus they fell into the orbit of the Mother personality’s jealous interest. A vicious circle.

Norman Bates’ house on the hill next to the hotel was “his whole world.” Just like the house where the dominant Augusta forcibly locked her son. In the first year of Ed Gein’s incarceration, a group of townspeople, in an act of powerless revenge, set fire to the building, reducing it to its foundations. Upon hearing this, Ed Gein shrugged and said, “Well, that’s good.”