ANIARA. Pessimistic Science Fiction with a Philosophical Message

An existential drama set against a science fiction backdrop – Aniara.

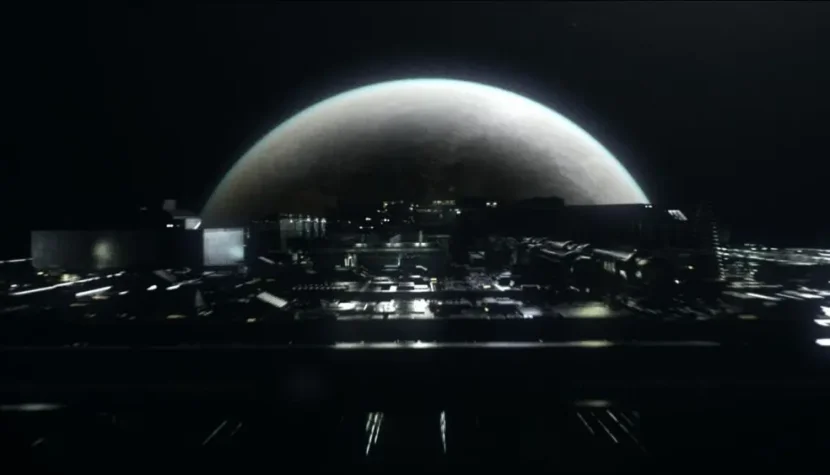

In an unspecified future, Earth—devastated by environmental pollution, natural disasters, and rising sea levels—is no longer habitable. Humanity relocates to colonies on Mars. The interplanetary journey takes three weeks and is carried out aboard enormous, self-sustaining luxury space shuttles like the Aniara. These shuttles feature restaurants, discos, swimming pools, gyms, video game arcades, and Mima, an advanced artificial intelligence that generates virtual reality experiences simulating Earth’s natural environment before the climate catastrophe.

During the first week of the journey, space debris breaches the Aniara‘s hull and damages its nuclear reactor. To prevent a meltdown, the crew jettisons all the fuel, resulting in the loss of propulsion and causing the ship to drift aimlessly into uncharted space.

The Aniara is an adaptation of a science fiction poem written by Swedish Nobel laureate Harry Martinson in 1956. In Sweden, it holds the status of a classic—an iconic national treasure that has deeply influenced other works of literature (Tau Zero by Poul Anderson, A Fire Upon the Deep by Vernor Vinge), theater (Aniara: Fragments of Time and Space), opera (Aniara by Karl-Birger Blomdahl), and music (Aniara by Kleerup, 31 Songs from Aniara by Tommy Körberg, and The Great Escape by Seventh Wonder). The first film adaptation, a black-and-white, low-budget production, was made for Swedish television in 1960. The newer Aniara film from 2018 had a budget of nearly two million euros, a significant amount for an independent European science fiction movie.

Martinson explained that the title of his poem means “the space in which atoms move,” likely derived from the Ancient Greek word aniaros (ἀνιαρός), meaning “desperate” or “sorrowful.” This aligns with the atmosphere of the film by Kågerman and Lilja, as Aniara is a work steeped in despair and pessimism. The once-thrilling voyage soon devolves into a purposeless drift through space, transforming the luxurious ship into a flying sarcophagus. Humanity, initially proud of its technological achievements and confident in their reliability, is ultimately powerless against the forces of nature and its own flaws.

The ship’s journey through Pascal’s “eternal silence of infinite space” evokes varied reactions among its passengers: some seek solace in virtual reality, others engage in religious cults, and still others indulge in sexual orgies. The most desperate commit suicide.

One might sarcastically label it “Titanic in space.” In truth, however, Aniara resembles Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) seen through a distorted mirror—or rather, its negative. Kubrick’s iconic film depicted humanity’s progress and expressed hope for a transformation into a higher state of being. By contrast, in Kågerman and Lilja’s film, humanity is doomed to regression, degeneration, madness, loneliness, and death. The ending hints that the cycle of life might restart on another planet. Yet, given the film’s premise (Earth’s destruction) and the events aboard the ship, what hope is there for this new humanity?

The doomed voyage of Aniara emerges as a metaphor for human existence itself: fragile, uncertain, often dictated by blind chance, and always moving inexorably toward its end. A bleak vision, but one that is hard to dispute. A thought-provoking film.