MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS (1974): The best-cast film in history

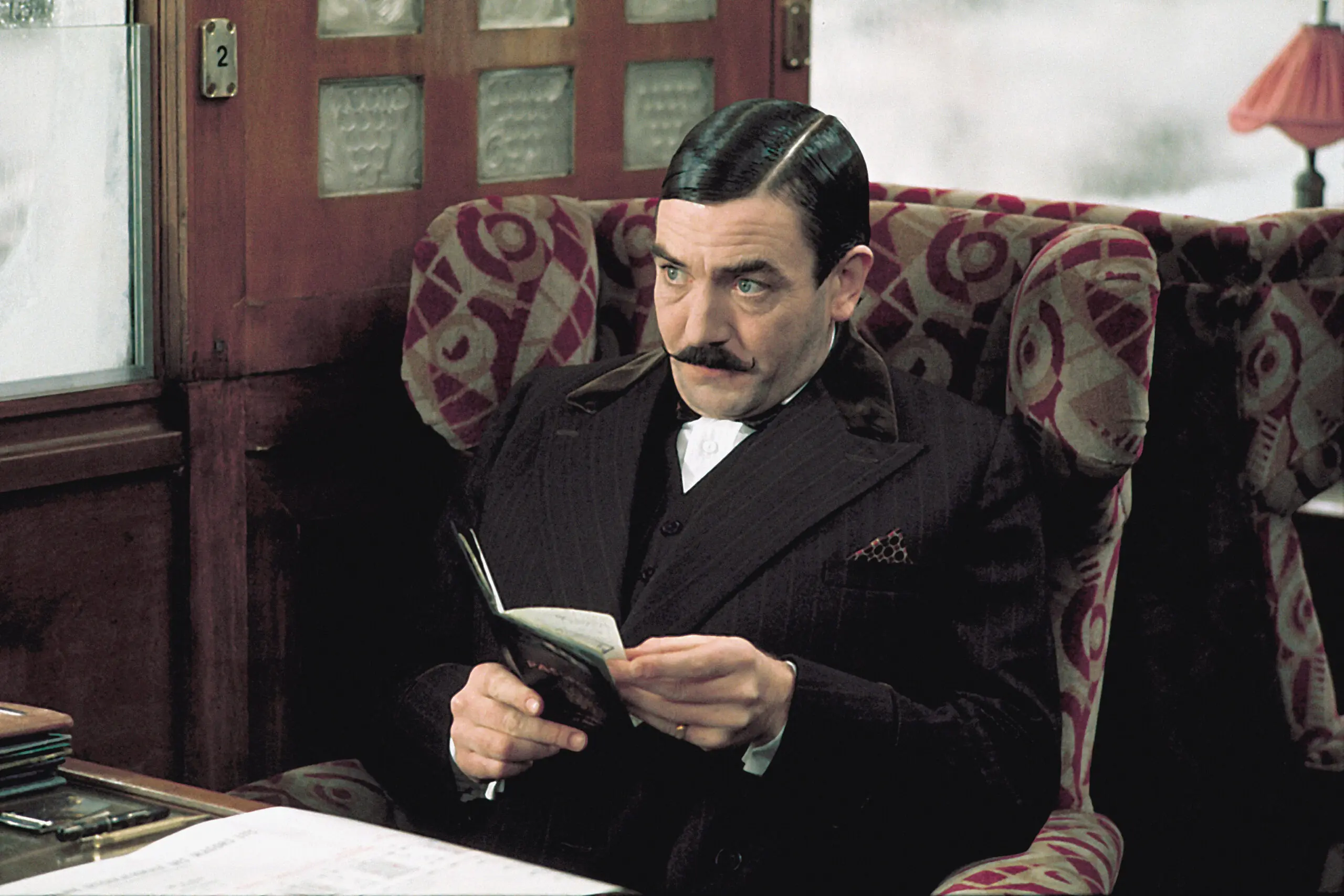

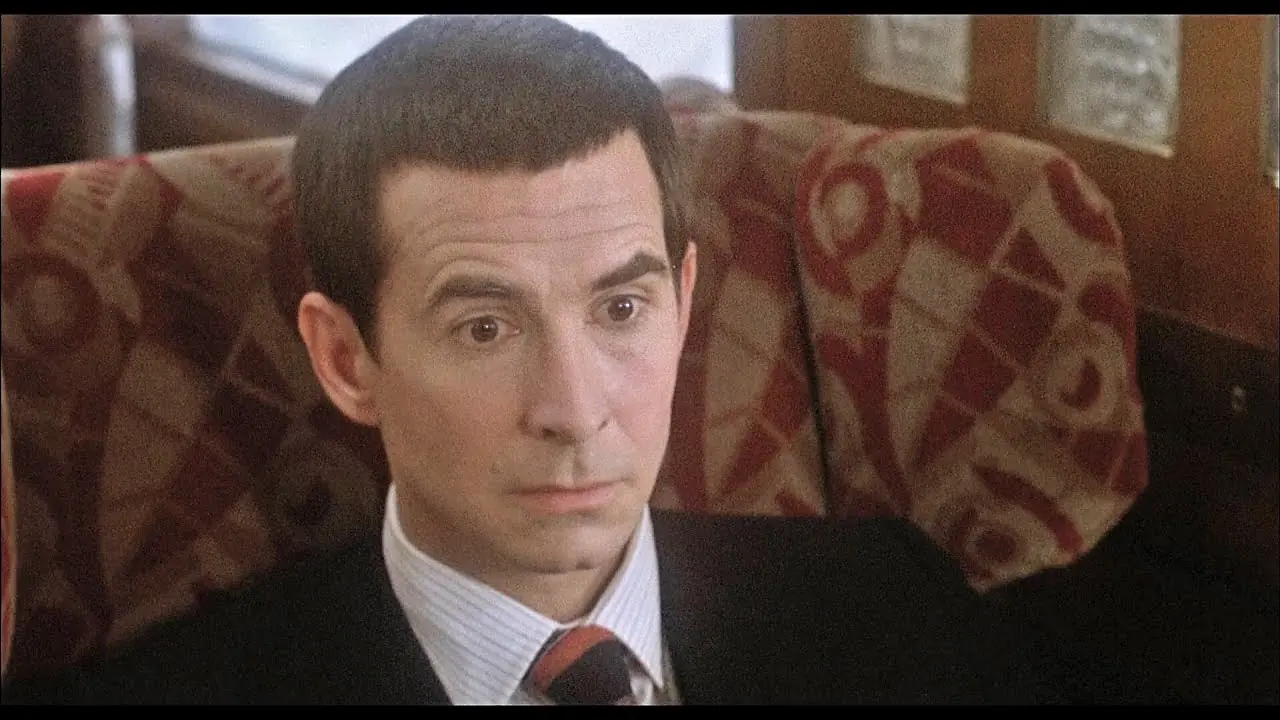

The ensemble consists of several dozen individuals—the passengers of a carriage traveling from Istanbul to Calais—and it is a stellar lineup. The leading role is played by Albert Finney as the peculiar Belgian with a brilliant mind—detective Hercule Poirot. Summoned to England on urgent business, he is granted, at the personal request of the company director Bianchi (Martin Balsam), a free bed in a compartment already occupied by a young Englishman, McQueen (Anthony Perkins).

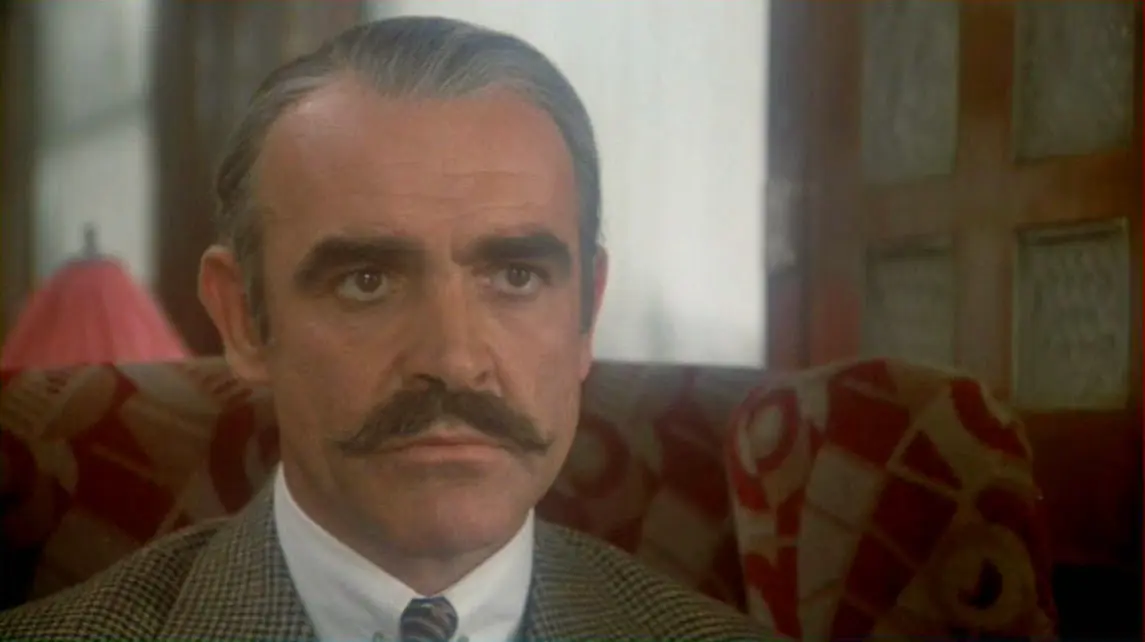

He secures this spot almost miraculously, as, to the surprise of the staff, the usually empty Orient Express at this time of year is exceptionally crowded. McQueen, along with the valet Beddoes (John Gielgud), accompanies retired businessman Ratchett (Richard Widmark) on his journey. Poirot had already encountered two of the passengers during the crossing of the Bosphorus Strait—Mary Debenham (Vanessa Redgrave), sharing a compartment with the fervently religious Swede Greta Ohlsson (Ingrid Bergman), and Colonel Arbuthnot (Sean Connery), enjoying the privileges of first class and traveling alone. In first class, one can also meet the fabulously wealthy Russian aristocrat Princess Dragomiroff (Wendy Hiller), tended to by her loyal maid Hildegarde Schmidt (Rachel Roberts), as well as the holder of a Hungarian diplomatic passport, Count Andrenyi (Michael York), and his picture-perfect wife, Elena (Jacqueline Bisset). Murder on the Orient Express it is.

A particular nuisance for valet Beddoes is his compartment mate, the boisterous Italian Antonio Foscarelli (Dennis Quilley), while, on the fringes of events, there are glimpses of the conductor Pierre Michel (Jean Pierre Cassel) and the inconspicuous Mr. Hardman (Colin Blakely). Regardless of whether the passengers travel in first or second class, regardless of their gender, social status, or eloquence, they are all overshadowed by the unbearable Madame Hubbard (Lauren Bacall), an American who never stops talking, sharing her life observations inherited from her second husband.

This multinational group of people, differing in personalities, temperaments, and mindsets—Swedes, Germans, Russians, Italians, Americans, Englishmen, a Hungarian couple, a Frenchman, a Belgian, and even a Greek!—is forced by circumstance to reside practically under one roof during their journey. Unexpectedly, one more event will unite them: the train is stuck in snowdrifts, and the unpleasant Ratchett—who unsuccessfully attempted to hire Poirot as a bodyguard and who, according to his secretary, had previously received a series of threatening letters—is found dead, stabbed twelve times. Who is the culprit? Is one of the passengers responsible for the murder, or did an intruder sneak onto the train? Could it be mafia-related dealings? Or perhaps someone’s personal revenge? Before the matter can be handed over to the Yugoslavian police, Poirot must investigate and uncover who killed Ratchett.

Agatha Christie’s book is a sophisticated mystery with a convoluted plot, and Poirot’s investigation is sheer intellectual labor. Lumet’s film, however, is something more. The director’s approach might even irritate those expecting a pure crime narrative. Poirot himself gives much food for thought. From Christie’s novels, we are familiar with his flaws: vanity, arrogance, meticulousness, sensitivity about his appearance, a love for symmetry, excessive pompousness—all these traits are exaggerated by Finney to the point of absurdity. His Poirot is utterly grotesque, in a theatrical manner, more akin to Molière than Shakespeare. Yet just when we are on the brink of declaring it overdone, we find ourselves surprised to realize we’ve been deceived—just like many who dismissed Hercule as a “ridiculous little man.” Finney achieves the impossible—allowing viewers, traditionally accustomed to the idea of a “brilliant detective,” to doubt the power of his little gray cells.

Simultaneously, with incredible acting finesse, he reveals Poirot’s psychological manipulation techniques: for instance, how he approaches interrogated passengers, using a different method for each—jovial with Beddoes, assertive with the colonel, nurturing with Greta Ohlsson. The theatrical presentation style adopted by Lumet works brilliantly, as every role occupies a defined space in the narrative, ensuring that each scene belongs to one or two actors. Strong artistic personalities don’t overshadow one another; rather, each is given full scope to shine.

Thus, John Gielgud’s seemingly minor role becomes the ideal archetype of an English valet: impeccably trained, cool, rigid, yet subtly humorous. The Count’s idolatrous love for his wife is theatrically highlighted. Similarly, the aristocratic refinement of the Russian princess is exaggerated. The pinnacle, however, is Anthony Perkins, suspected of an Oedipus complex—his timid, nervous nail-biting demeanor clearly references his famous performance in Psycho. And who else could portray a religious fanatic like Ingrid Bergman, the actress famous for playing Joan of Arc?

Lumet’s film is a masterful play with stereotypes, schemes, and patterns ingrained in theater and cinema for decades, which can only be taken half-seriously once we realize that Christie’s novel serves merely as the foundation upon which the director built his cinematic theater—a starting point for his own ironic, subversive, and extraordinarily clever vision.

Among all the outstanding acting performances, Lauren Bacall shines brightest, finding the golden mean for her portrayal of Mrs. Hubbard. Readers of the book know that among all the characters, Madame Hubbard is the most grotesque: loud, somewhat trivial, excessive in everything. In the film, where everyone else is equally grotesque, Bacall plays her role with remarkable subtlety. And thus, she stands out and excels exactly as she should.

Murder on the Orient Express is a unique actor-driven film and the only adaptation of an Agatha Christie mystery that the author herself fully appreciated. It garnered numerous accolades, including an Academy Award for Ingrid Bergman and nominations for Albert Finney, cinematography, costumes, music, and screenplay. It is recommended for anyone who appreciates artistic acting and films where the director’s skilled hand is evident in every frame. Also, for those who haven’t read the book—due to its truly ingenious resolution of the mystery.

Trivia:

Ingrid Bergman was considered for the role of Princess Dragomiroff, described as an aged lady, the ugliest Poirot had ever seen—a remarkable kind of ugliness, more fascinating than repelling.

Albert Finney was the third choice for Poirot, after Alec Guinness and Paul Scofield.

Parodic references to the film can be found in Murder by Death as well as Scary Movie.

The film was nominated for an Edgar Allan Poe Award in 1975 but lost to Chinatown, with other nominees including Coppola’s The Conversation.