THE CONGRESS. Great piece of Lem-inspired sci-fi animation

The Congress is divided into two parts, very different from each other in theme and form. The link between them is the Hollywood star Robin Wright, who plays… herself. She is invited by the head of the Miramount studio (a charming play on words, not the only one in the film, by the way) for a meeting regarding a completely new role. He offers her “the last contract she’ll ever get”: scanning her image for the studio’s use, which can then do whatever they want with “her.” Seeing this as an opportunity to spend more time with her sick son (played by Kodi Smith-McPhee known from Let Me In, among others), the actress—very reluctantly—agrees to the procedure. So, her character is recorded in the computer: voice, facial expressions, gestures—everything for use in any Miramount project.

This entire segment of The Congress is an excellent satire on the world of film: the boss (fantastic Danny Huston) spins an extraordinary vision for the actress, where big studios no longer have to “lose millions” on the whims of stars; where actors take on all roles, regardless of their quality. “We don’t want you!” he finally says to her, “We want Jenny from Forrest Gump, we want Buttercup from The Princess Bride!”. There is something authentic in this vision—the feeling that technology will eventually be capable of such procedures. Well, one doesn’t have to look far— Avatar perfectly proved that computers can eventually become an integral part of acting. So why shouldn’t it replace it?

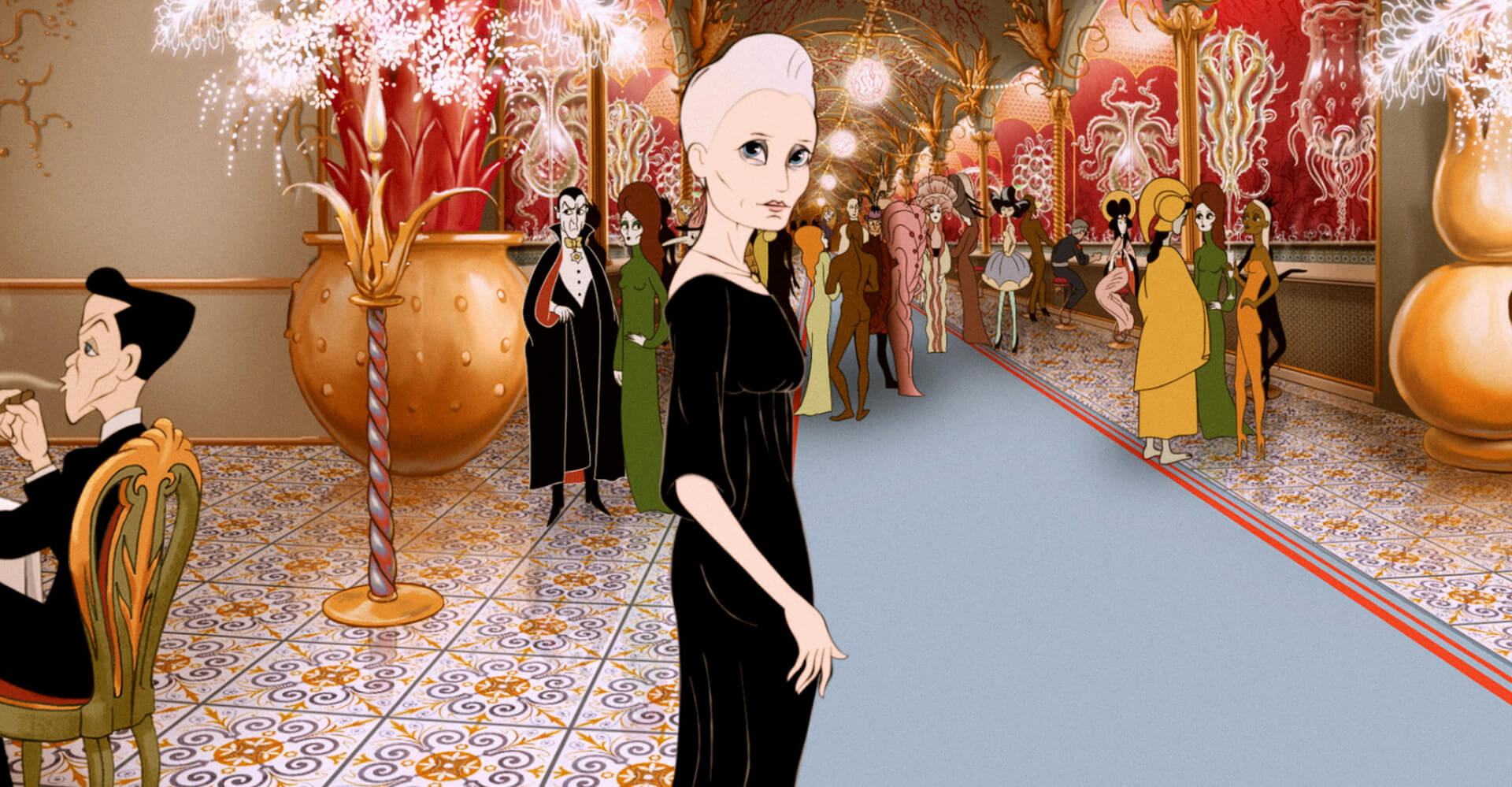

Twenty years pass, during which Robin Wright is still a star. Meanwhile, her real version is invited to the Futurological Congress, held at the Miramount studio hotel. However, entry to the Conference involves the use of a chemical substance that distorts reality, turning the world into a crazy animation reminiscent of the 1940s. This is where the second part of the film begins, in which the animated Wright enters the absurd world of people liberated by technology from a specific form. Everyone can be whoever they want: their favorite celebrity, an animal, or even Jesus or Buddha…

Folman’s work quickly changes from film satire to a story about a sense of identity in a world where everyone prefers to wear masks rather than be themselves. Robin struggles between truth and fiction, discovering a world that, as a result of the “chemical revolution,” has turned into an abstract cartoon where who you were doesn’t matter, and everyone can be “Robin Wright.” In the end, everyone becomes mere copies of someone else, devoid of personality, mannequins with the faces of models, artists, gods. The film emanates a strong fear for the future of our species, which continues to undergo a process of self-improvement, regardless of the cost and without regard to any boundaries—psychological sensitivity, morality, or simply common sense. We make life easier in every possible way; we want to be faster, healthier, more beautiful, we want to live in luxury and abundance. The Congress thus shows a quite real—and at the same time very painful—solution to this unattainable dream of humanity.

However, it is primarily a story about Robin Wright—a very personal and sincere story. This is largely due to the actress herself, whose role is very self-reflective yet full of unexpected humility. Perhaps one of the finest scenes in the film is when the actress undergoes the scanning process, while her manager (the very good Harvey Keitel in a short but moving role) tries to keep her spirits up. It’s truly an outstanding segment, brilliantly played by both actors and undoubtedly possessing something very authentic and touching. I feel like this role has become a kind of mirror for Ms. Wright, a test of confronting her own career, weaknesses, and fears. Folman also skillfully leads the “filmic” Robin and her “family” subplot. The desire to reunite with her son and daughter motivates her actions, fuels her narcotic visions, but also keeps her “afloat.” Because ultimately, what truly allows us to maintain our identity and shapes our personality are the people we love.

One should not forget about the excellent form of The Congress. The live-action part of the film looks good, mainly due to Michał Englert‘s very good cinematography and the captivating beauty of Robin Wright. However, what happens in the animated part is jaw-dropping. From the initial graphics, one could infer that Folman would again opt for a realistic style, as he did in Waltz with Bashir. However, apparently, this form was so exhausting in terms of production that the creator decided to simplify the animation, reminiscent of the classics of the 1940s like Popeye or early Disney animations. In my opinion, this benefited the film because this type of animation has something wild, crazy, unpredictable about it, but above all, a certain difficult-to-define fluidity and transformative quality. It perfectly complements the world of The Congress, which is still alive, transforming, changing, and distorting. When we add to this the riot of colors, the variety of images, and the incredible directorial imagination, we get a visually stunning picture, but not devoid of emotional power. One should not forget about Max Richter’s music (the author of the excellent soundtrack for Waltz with Bashir), which is phenomenal and wonderfully builds the unique atmosphere of the film and the variable character of the world presented in it. I have a feeling that this will be a piece for repeated listening.

Undoubtedly, The Congress will divide critics much more than Waltz with Bashir, but it’s not hard to see why: Waltz… is a story with a strongly documentary character, while The Congress is less structured in terms of plot, focusing on the personal drama of a lost actress, her world of experiences, and observations, which brings this film closer to projects like Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York, Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, or Satoshi Kon’s Millennium Actress. Some people might be put off by the abstract form, while others might be discouraged by the slight connection to Lem’s story. However, it’s worth giving The Congress a chance because it’s not easy cinema, but it’s moving and, behind its visual splendor, hides several very poignant reflections.