SOLARIS (2002). Great piece of Lem’s Sci-Fi made in Hollywood

This fact is not surprising considering the multi-layered nature, narrative style, and philosophical depth of his works.

In this context, the opinion of Lem, published after the premiere, regarding the adaptation of his novel Solaris, written more than half a century ago, seems surprising. Striving to assess Solaris as a potential material for a film, I come to the conclusion that it is hard to find something more challenging and presenting more formal obstacles than the novel by the Polish writer, which is already part of the strict SF canon. However, assuming that the author’s words are the best recommendation, I went to the cinema full of cautious optimism. I was not disappointed; Solaris is a piece of great cinema, allowing for multiple interpretations and inspiring deep reflections on the essence of humanity, and the director-actor duo: Soderbergh – Clooney proves that they have more to offer than just superficial entertainment in the style of Ocean’s Eleven.

Chris Kelvin (George Clooney), after the death of his wife – Rheya (Natascha McElhone), lives alone – aimlessly, day by day, out of habit performing actions that make up his existence. One day, representatives of the space agency approach him with a recording sent from the Prometheus space station orbiting the planet Solaris. The recording contains a mysterious request from Dr. Gibarian – Chris’s friend, who sees in him the only hope to resolve the critical situation in which the station’s inhabitants find themselves. Gibarian hesitates to provide details of the situation, but there is a justified suspicion that the health and lives of people may be in danger. Chris embarks on a journey, but upon reaching his destination, he finds out that his friend has committed suicide, and there are only two living people left on the station. At least that’s what he thinks.

It’s probably worth starting with what wasn’t included in Soderbergh’s film. According to Lem’s own announcements and comments from viewers who have seen the film, there was a lack of the Solarian ocean thread, which in the novel is the main causative factor of all events taking place on the station. This also excluded the rich descriptions of the ocean’s creations and philosophical considerations about the possibility or rather impossibility of communicating with a form of intelligence that eludes any human classification, lying beyond human ways of understanding and thinking about the surrounding reality. Paradoxically, the omission of this extremely important thread did not diminish the message of the film; Soderbergh simply focused on the second – equally important motif – the relationship between Chris and Rheya/Harey. Their mutual relationship became the axis of the plot. Chris arrives at Prometheus unaware, he does not know what has happened, he does not know what to expect, his professional skills may be useful for saving its inhabitants. What he finds on site puts his mind, and along with it the viewers, against the wall of ignorance. Snow and Gordon – inhabiting the station – show no willingness to explain anything, allowing Chris to experience the atmosphere of Solaris on his own.

The key is the dream – the first night. The psychologist is confronted with his own imaginings, projections of his own mind, his guilt finally. The appearing out of nowhere Rheya becomes on the one hand the embodiment of his conscious desires, and on the other a living reproach, a woman he remembered from the last moments of her life, a life she took herself. Chris feels guilty for her death and treats the situation as a second chance, a divine intervention that will allow him to free himself from the yoke of guilt, a chance for fulfillment in love. The scientist’s soul is dominated by emotions, however irrational they may seem. This is another difference between the literary prototype and the film’s plot. Lem equips Kelvin with a strictly scientific mind, whose approach to the phenomenon is much cooler, even suspicious. Soderbergh’s Chris is above all a deeply unhappy man – a scientist with an unhealed soul wound.

Such a man’s attitude is confronted with the attitude of Harey/Rheya. The woman being a projection of Chris’s memories, a living image preserved in his memory, is not just a phantom – a puppet, a part of an experiment of an unexplored and incomprehensible power of the “mind” of Solaris. Rheya is a woman endowed not only with a body but above all with the consciousness of her own existence, equipped, however, not with her own memories, but imprinted somehow in the psychic matrix of Chris’s impressions. Her awareness lies at the heart of the tragedy unfolding before our eyes. The awareness that she is only an ectoplasmic cast of a form created in the husband’s mind determines that she does not feel fully human. This raises a wealth of questions about what makes us human, about the essence of our existence. By the way, the issue of the cause of the events we see on the screen also arises. Soderbergh does not offer us easy solutions. Here appears, in a way, the shadow of the “great absent” – the Solarian ocean, which takes on divine traits – realizing dreams, or perhaps just experimenting in its infinite intelligence on a less developed species, which is human.

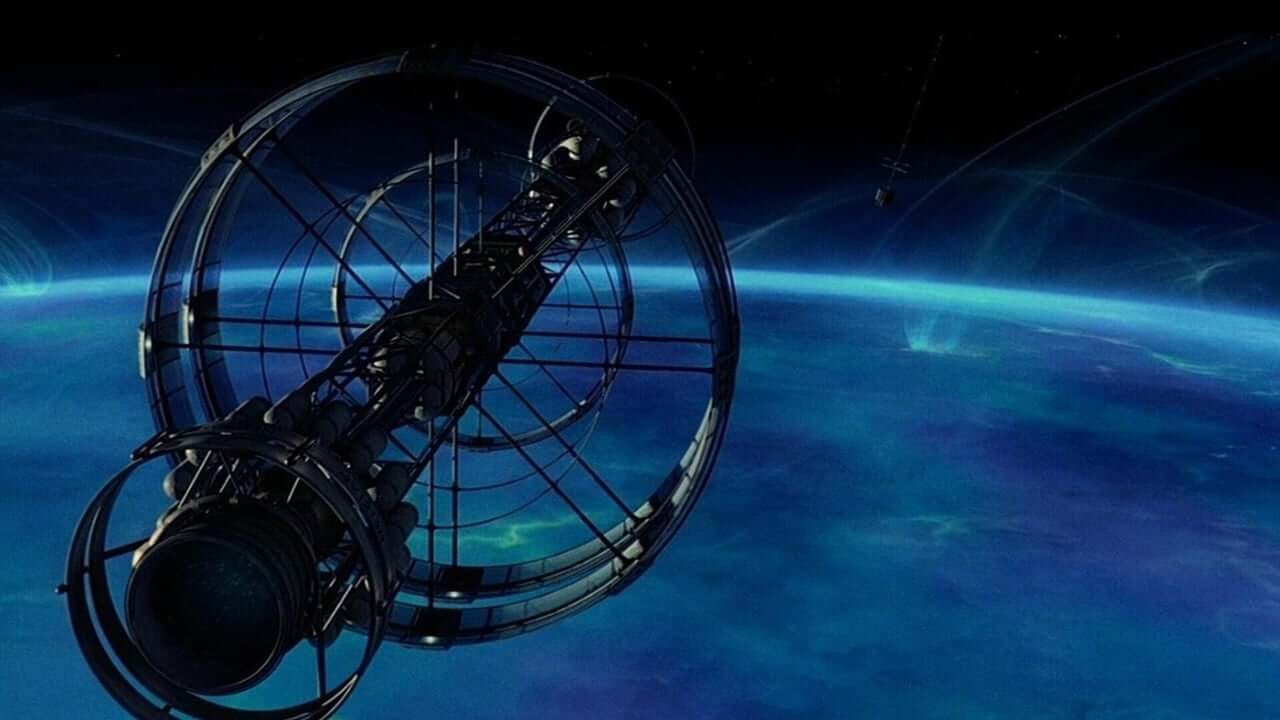

Not a single word in the film mentions the ocean as any form of intelligence or being. However, in one of the scenes, there is a subtle suggestion – a contribution to the discussion about the nature of divinity. In this way, Soderbergh, although seemingly omitting the extremely important thread of the novel, which is the issue of Contact, very delicately and without a hint of literalness, gives the viewer something to think about regarding its nature. This is a narrative delicacy that can be interpreted rather only by very attentive viewers who are familiar with Lem’s novel, nevertheless, it shows Soderbergh’s excellent sense of the original atmosphere as a screenwriter. Soderbergh – the director unfolds the action of his film before us without hurrying, allowing the viewer to analyze the situation, enabling to marvel at the Prometheus soaring in the vastness of cosmic vacuum (whose name in the context of events on Solaris becomes a kind of irony – the hero Prometheus interferes again in the affairs of gods), and with precise, but devoid of excessive details, scenography.

Soderbergh’s film is a piece of great science fiction cinema, closer in narrative style to Blade Runner and 2001: A Space Odyssey than to series like Alien or Star Wars. It combines the advantages of Scott’s and Kubrick’s masterpieces – touching on the essence of the Unknown (the Solarian ocean evokes spontaneous associations with Kubrick’s monolith) but not avoiding the question of its influence on what is most human – emotions.